On a frigid Saturday afternoon in January, Brad Balliet—a virtuosic woodwind player—delivered news that would change my life. We sat across from each other at a battered steel desk in a basement workspace at Sing Sing Correctional Facility in Westchester, New York. Beyond the electric fence outside, Metro-North trains tore by, roaring through our conversation and the prison itself.

Brad and I had met eight years earlier when I enrolled in Musicambia and Carnegie Hall’s Musical Connections, programs that connect professional musicians with incarcerated artists. Within the confines of one of the world’s most notorious maximum-security prisons, I started to learn music theory. I listened to the way instruments sounded, dreamt up harmonies and rhythms on a spare keyboard, and jotted down notes on manuscript paper. Brad watched me grow from a nascent artist to a composer across various genres: folk, classical, jazz, and opera.

Over time, Brad became not just a mentor, but a collaborator—someone who saw what my music could become beyond prison walls. So when he returned years later with a proposal that could change everything, I listened closely.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Inquest, finalist for the 2025 National Magazine Award for General Excellence, brings you insights from the people working to create a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest in your inbox every Saturday.

Newsletter

By then, Brad was used to the cacophony of our visits—the echo of instruments played in rooms nearby, the shouting from the recreational yard, the rumbling trains in the background. The sounds of the education wing, however, were a welcome contrast to what I usually heard: radios blaring out the latest drill tracks, men yelling from cell to cell about food or cigarettes, and officers slamming gates in the housing units.

Brad, a wiry fellow with round, wire-rimmed glasses to match, leaned back in an office chair. A cushion popped out from its side, probably from an earlier search. “We have secured a grant to produce an opera of yours and perform it at the hall,” Brad said with a smile. “If we do, we’d need the score by the second week of April to give the musicians and singers enough time to learn the music and rehearse.”

“I can do it,” I said, pulling my tongue from the roof of my mouth. I was not sure who I was reassuring more, Brad or myself. A few minutes later, we nodded our goodbyes. I turned, glanced through a plexiglass window on the door, and hurried down the hallway toward an office where I liked to compose.

I sat. I played. Soon, I began to write.

I fell in love with opera in 2015. That year, the acclaimed mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato came to Sing Sing as a visiting artist. She performed traditional arias for us, as well as music that we all wrote together. For three more years, she returned to Sing Sing, and with every visit, my love for the genre deepened. Writing stories and poems, and listening to music, helped me find refuge during my adolescence—a time when I experienced sexual abuse in my household. Opera lets me explore both avenues, a genre where the emotion of a narrative is bolstered by music.

At the same time, opera was utterly intimidating. I sat in front of my keyboard, tan-knuckling a pencil. It’s common for artists to spend years completing a single opera—and that is with access to all the amenities and inspirations of the real world. I wondered how I was going to write and compose a three-act opera within ten weeks, and despite the trappings of prison.

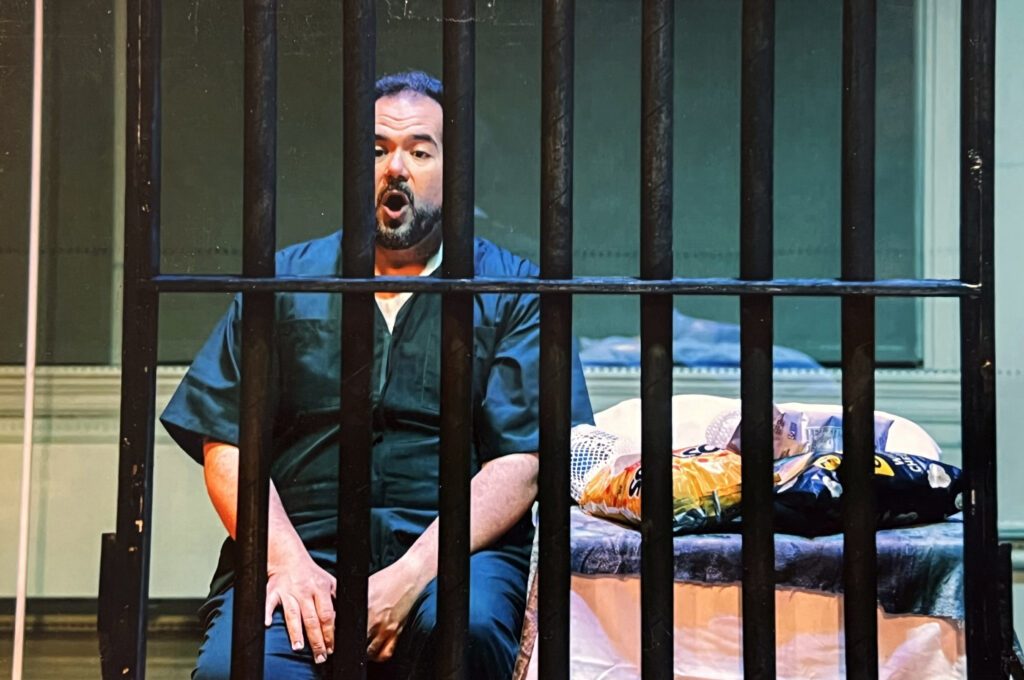

In 2020 I began writing about the pandemic, reflecting on the death, isolation, and fear surrounding me. And for years before that, I had kept a book of manuscript paper loaded with melodies I had jotted down. These two collections of documents would give birth to 9131: A Sing Sing Opera. 9131—titled after the number of days in a twenty-five-year prison sentence—gives the audience a glimpse into the internal conflict of a man longing for release while grappling with what true freedom of body and soul really means.

In the days that followed my meeting with Brad, I started putting the story together. First, I needed a protagonist. My audience would be mostly white and affluent, I imagined. How could they ever relate to the experience of incarceration? I chose to make my protagonist white, someone who had awakened to the realities of mass incarceration and systemic injustice through his experience.

I asked myself questions. How long would it take for a white, affluent man to become entrenched in prison culture? More than fifteen years. Why would a white, affluent man spend more than fifteen years in prison? Murder. What would follow twenty-five years of his incarceration? A developed sense of empathy. Full assimilation into prison life. How would he approach the parole board? Fearfully.

It was important to me to highlight the realities of incarceration—both its impact in the present moment and the ways it shapes one’s future. The audience has to witness the humiliation of a strip search, late-night conviction in a lonely cell, separation from loved ones, I thought.

In February, I began writing out the opera’s libretto, or text. I could not do it alone. I had responsibilities as an Osbourne Association clerk and caregiver, and a Hudson Link college student. I needed help. Luckily, I had a longstanding friendship with Zontiell Gordon, a tall, slender spoken-word artist also incarcerated at Sing Sing. We met while working at the prison’s library and quickly bonded over our love of stories and words. I proposed that we write an aria together and he agreed.

All I had was a refrain, an homage to the 1937 anti-lynching ballad “Strange Fruit”: Fire roasted strange fruit. They find shade. Frenzies abate. I wrote it down and sent it to Zontiell. Through a series of kites—or letters distributed throughout the prison through a network of friends—he and I wrote the words to an aria, “Canned Strange Fruit.” The aria draws on food preservation as a metaphor for the legacy of slavery. Lynching, the horror so vividly featured in “Strange Fruit,” lasted minutes. But the suffering of incarceration, in steel cages called “the can,” often lasts years, decades, lifetimes. Just as the can preserves food, the modern prison preserves the depravity of the abuser and the pain of the abused.

Last was the painstaking work of setting it all to music. I had written out all of the melodic lines, but needed to give them a body, a harmony. Here I leaned on another companion, He Xiaobao. Another Sing Sing resident, Xiaobao is a laid-back Chinese bebop musician and classical guitarist with a K-pop look. We blended our knowledge of multiple genres to create a harmonic backdrop that would sound unexpected yet familiar.

I turned in the score on the second Saturday of April. It was not complete; in the end, I submitted two out of three acts. Brad assured me that it was good enough, more than expected given the time I’d had.

On the night of the concert, I decided to call my sister Myosha. I was in a room lined with phones, about four on each wall. It was directly across from the showers, and steam drifted through the already hot, unventilated cinder block cube. I dialed Myosha’s number and waited through silence that is trilling in the outside world. She picked up.

“Hello, sista,” I said. I could hear my music in the background.

“I’m at your opera,” Myosha responded. “I don’t want to miss it.”

“OK, love you, talk to you soon,” I said, and hung up the phone. I did not want her to miss it either. Over the years, my sister has gone to Carnegie Hall on my behalf to hear music I’ve written, performed by artists including Rhiannon Giddens, Sarah Elizabeth Charles, and Mwenso and the Shakes. She was an adolescent when I was arrested. Now, two decades later, in her thirties, this is how I spend time with her—giving her something to be proud of. Hoping, maybe, she can find some pride in what grew from my shame.

I was given ten weeks to complete 9131. I wrote it frantically, between obligations, playing line after line over and over again. Instead of socializing or exercising, I imagined what a character might say, might feel.

But the truth is, 9131 wasn’t written in ten weeks—it took over eight years of work and friendship to pull off. Every melody I saved, and every moment I spent connecting with fellow musicians, inside and outside prison walls, was crucial. I made it to Carnegie Hall because I practiced, practiced, and practiced—not just at being a composer, but at being a friend.

On June 9, 2023, an audience at Carnegie Hall witnessed an opera written by a person who had been convicted of murder, in collaboration with his fellow incarcerated artists. Over two years later, this fact is still striking to me.

I have often felt conflicted by my accomplishments behind bars. Am I worthy of them? Do they erase my past? While these questions still cross my mind, I have concluded that, for me, accountability is struggle, is constant work.

Every day, I work to leave the old Joseph behind, in the hopes that his misdeeds can fuel metamorphosis. I still study music theory, play my keyboard, and jot down melodies. I push myself to document the lives of incarcerated people through journalism and music. I’m not certain about what lies ahead, but I know that I’ll be ready for it. Or at the least, I’ll be ready to tell the tale.

Header: Orchestra during performance of 9131 at Carnegie Hall. All images courtesy of the author.