Martin Sostre had been appealing his case since the day he was convicted in 1968. He tried to hand his legal appeal to the judge on his way out of the courtroom. Five years later, after numerous protests and petitions, the state’s key witness—a police informant who helped to frame Sostre on heroin possession charges—finally prepared to recant his testimony. But between Sostre’s solitary confinement cell and the courtroom in Buffalo stood a group of seven guards insisting he submit to a mandatory rectal “examination.” Sostre resisted, as he had for years on principle, arguing that these were attempts by the state to destroy the last vestiges of his personhood and spirit. For this refusal, he was beaten and subsequently charged with assault himself. The attack was the first of eleven he sustained during his final three years of incarceration.

Sostre was a revolutionary thinker, organizer, and community educator who outlined a radical vision of individual freedom and collective liberation from conditions of oppression and captivity. With clarity of purpose, he sought to create an egalitarian society free of coercion in which all people would enjoy the world in common. As an internationalist, he understood white supremacy, capitalism, militarism, and colonialism as interlocking global systems of power and regarded prison as a concentrated manifestation of the repressive state. Dismantling these structures, he believed, was necessary to bring a new world into being. At the height of his prominence during the 1970s, Sostre was one of the most well-known political prisoners in the country. On August 12, 2015, Sostre passed away at the age of ninety-two. In accordance with his wishes, his family did not publicly announce his death. Four years later, the New York Times belatedly eulogized him as a “pioneering fighter for prisoners’ rights.” But Sostre was also a key progenitor of contemporary Black anarchism and abolitionism, even though his contributions to these areas are virtually unknown today.

Now at the centennial of Sostre’s life, it is important we understand his ideas and commitments through his actions. “A dynamic deed is something that really mobilizes people,” he said. One of the central principles of his unique political ideology, developed during nearly two decades in prison, was the relationship between collective struggle for liberation and each person’s fight to secure their own bodily autonomy and individual freedom. “The struggle for liberation,” he explained, “ultimately boils down to the individual exertion of his or her faculties to the fullest extent.” Sostre considered individual resistance to state violence the most concentrated form of revolutionary struggle, making his protests against sexual assault in prison and his assertions of bodily autonomy simultaneously necessary for his own personal freedom as well as symbolic of a worldwide struggle. His refusal to submit to state-sanctioned sexual assaults remains one of his most significant and lasting legacies. It is especially urgent, as millions held captive in prison and jail face similar routinized violations today. To appropriately assess and learn from Sostre’s life, we must recognize the relationship between the freedom of one person—or a single act of resistance—and the collective liberation of all oppressed people.

Sostre was first politicized while incarcerated during the 1950s. He taught himself law, studied philosophy and history, and began practicing yoga. In 1957 he sued New York’s parole board for its all-white racial composition. Soon he and other Muslims in the state initiated the first organized prison litigation movement, arguing for their right to worship, to access the Qur’an, and to engage with religious advisors in person and through the mail. For his activism, he served the maximum of his six-to-twelve-year sentence, nearly the final half in solitary confinement.

Following his release in 1964, Sostre moved to Buffalo, where he worked at a steel mill and saved money to open a radical bookstore. Along with those in Detroit and Philadelphia, Sostre’s Afro-Asian Book Shop was one of the earliest examples of a Black-owned, anti-capitalist, community-oriented bookstore. Student activists from nearby universities and local youth on Buffalo’s East Side lingered in Sostre’s store, reading books and pamphlets by Malcolm X, Fidel Castro, Mao Zedong, Robert F. Williams, and other revolutionaries.

In 1967, when Buffalo became a site of Black rebellion, Sostre’s bookstore served as a prominent site of politicization. “I had something concrete that was currently happening right outside for everyone to see—namely, the invasion of the Black community by droves of white armed police who were indiscriminately shooting tear gas and bullets, beating up and arresting Black men, women and children and committing other depravities,” Sostre wrote. “No one could argue against these concrete facts.” He stayed open late, sharing literature, giving speeches, and offering a refuge to those tear-gassed in the streets. Within weeks, the store was raided by police, state troopers, and the FBI; Sostre and his coworker Geraldine Robinson were arrested for allegedly selling a $15 bag of heroin to an informant. After eight months languishing in jail without money to pay his excessive bail, Sostre was convicted by an all-white jury and sentenced to thirty-one to forty-one years in prison.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

In the years between his arrest and his 1973 trial, Sostre remained a prolific jailhouse lawyer. In 1969, he won a landmark prisoners’ rights case in which U.S. District Judge Constance Baker Motley ruled in a sixty-six-page judgement that Sostre’s term in solitary confinement constituted “cruel and unusual punishment.” She awarded him $13,000 in damages, to be paid by prison officials, and returned 124 days of earned time he had lost while in solitary. Tom Wicker of the New York Times called it a “startling, perhaps historic, decision.”

Part of what Motley had found to be “cruel and unusual punishment” was the state’s practice of mandatory rectal searches. For over a year, Sostre had chosen to give up his one-hour allotment outside his cell rather than submit to these assaults. He spent 372 days, 24-hours a day, in a cell instead. “They may succeed in beating me to death,” he wrote to one federal judge, “but they shall never succeed in forcing me to relinquish what in the final analysis are the final citadels of my personality, human dignity and self respect.” Trapped in an escalating war between his body and state domination, Sostre defended what he considered the last bastion of his personhood. “To me it’s a worse injury to [submit] than to take that beating,” he said. At least then, he declared, “I would maintain my spirit unbroken.”

On May 19, 1973—the day Sostre traveled back to Buffalo for his appeal—he survived the first of eleven beatings by prison guards for his resistance. He was knocked to the ground and punched “viciously and calculatedly” in the kidney until he was limp. He tried to file a lawsuit, but the state held up his paperwork, meanwhile charging him with assaulting the guards. Under New York’s “persistent felony laws” (a precursor to the more well-known “Three Strikes” laws of the 1990s), Sostre faced a second life sentence. The contradictions were glaring. Nearly five years after his frame-up, the state’s key witness was finally willing to recant his testimony, perjuring himself in the process.

But to appear in Erie County Court and overturn his original sentence, Sostre was required to submit to further sexual assaults. When he tried to sue state officials for these violations, he was the one who ended up being charged. But it was precisely in this vicious circle where Sostre found opportunity and hope. “Struggle always brings out contradictions,” he said. It was only when confronted with such stark inconsistencies, he believed, that people could be recruited to join the revolutionary struggle necessary to a society free of domination and coercion. As the trial for his alleged assault approached, he wrote confidently: “I see this as a chance to expose their entire oppressive system. They’ve provided us with a forum to air all the barbarity and savagery that’s covertly taking place in the box (solitary confinement).” Sostre’s trial in Plattsburgh, New York, offered an opportunity to put to the test his thesis that individual resistance—and demonstrated action—could move people toward revolutionary action.

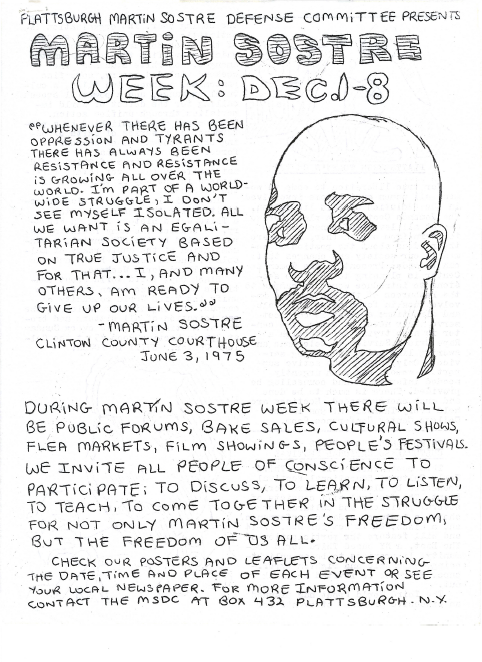

For the previous two years, a small group of young people in the city had been building a local Martin Sostre Defense Committee (MSDC) and preparing for the trial. Plattsburgh’s major industries had their origins in U.S. imperialism and labor extraction: a local military base established during the War of 1812 and a prison built during the 1840s that supplied cheap labor to local mines. Over a century later, many of the prison’s staff made the short commute from Plattsburgh to nearby Dannemora prison for work. As one sympathizer commented regarding jury selection, “Mr. Sostre has no peers in Clinton County.” Yet, under difficult circumstances and with little money or organizing experience, the Plattsburgh MSDC managed to make the upcoming trial a local and regional flashpoint. Radical lawyers from across the country, including William Kunstler, Liz Fink, Dennis Cunningham, Michael Deutsch, and Charles Garry, traveled to support him. “The whole world will be watching this trial,” wrote Antonio Rodríguez, the committee’s cofounder.

With the outcome of the trial likely to be decided by the composition of the jury, members of MSDC were tasked with finding out as much as they could about potential jurors. A nearby apartment equipped with a phone and Rolodex served as headquarters. When a juror was called for questioning, committee members scrambled from the courtroom to the apartment to find information on them. After 160 potential jurors were called over nearly two weeks, an all-white group was seated for the trial.

But even as Sostre faced a life sentence and a system stacked against him, his dignity and defiance permeated the proceedings. He smiled and chatted with comrades in the audience. His testimony and that of other imprisoned people in solitary confinement exposed the daily and often hidden atrocities of the prison. The court’s racist and fascist proceedings, meanwhile, laid bare the legal system’s façade of justice. The courthouse was full of armed police, and before the jury was even chosen, Judge Robert J. Feinberg had threatened to gag and bind Sostre (a repetition of his 1968 trial in Buffalo). “I’d rather deal with the devil’s advocate than the devil,” Feinberg said, referring to Sostre and his lawyers. During jury selection, Sostre and his cocounsel Dennis Cunningham asked potential jurors if they would consider their own conscience in the face of an unjust law. When one wavered and considered answering yes, she was corrected by the DA and dismissed from the jury.

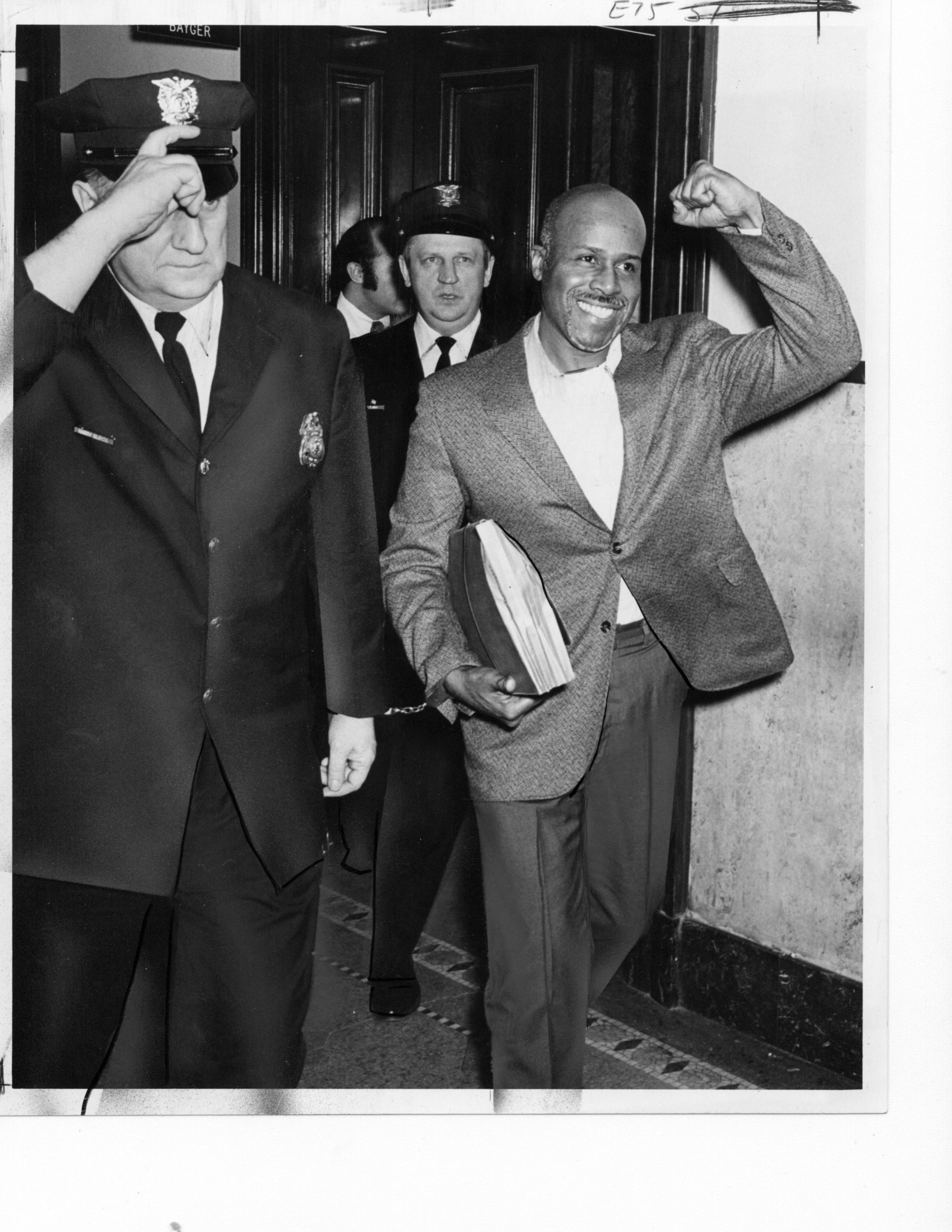

The trial made Sostre’s everyday resistance visible on a grander scale. Just as his refusal to submit to rectal assaults challenged other imprisoned people to either join in resistance or consent to coercion, the trial forced the people of North Country to face injustice in their own backyard and decide whether they would turn away. As the end of the trial approached, however, it was clear to many that a guilty verdict was a foregone conclusion. As a result, a group of supporters gathered the night before the verdict and decided they would stand in silent protest upon its pronouncement. Rodríguez would also read a brief statement. When Sostre was convicted as expected, Rodríguez stood and began to speak: “We condemn this trial as a frame-up and an example of systematic oppression and express our solidarity and support of Martin Sostre and the struggle for freedom everywhere. We stand because we feel that we are all on trial.” Dozens more joined and raised their fists. Chants of “Free Martin Sostre” filled the room. Tom Wielopolski, who been imprisoned with Sostre and assaulted for refusing rectal searches, cut through the chants when he shouted at the judge, “Fuck you pig.”

Police flooded the courtroom from all sides and Judge Feinberg shouted for arrests. A dozen supporters, most of them committee members, were handcuffed and taken to the jail. There, the group faced the issue at the heart of the trial: the strip search. Sylvia Rodríguez (Antonio’s sister), who was five-months pregnant, refused. “Not that I was so radical,” she explained, “but I was thinking, what would Martin do?” Another woman arrested, Betsy Boehner, was strip searched. The group of men faced a similar decision. Fearing that if they resisted, they would be assaulted and charged as Sostre had, the group decided to submit. “I have to say, we failed that moral test,” Antonio remembered. “We were ashamed about it.” Boehner recalled a similar feeling of regret.

That a group of a dozen young people went to jail protesting a racist frame-up they witnessed in court, and then considered refusing the strip search as a moral litmus test, demonstrated the effectiveness of Sostre’s efforts to bring the repression of the prison to the consciousness of those outside. His comrades did not simply bear witness to these injustices; they were willingly confronted with them. Others who were radicalized by what they saw at the trial soon formed another defense committee, in nearby Potsdam, New York. This group quickly grew, helping to organize an international clemency campaign which secured Sostre’s release on Christmas Day 1975.

Sostre envisioned this network of emerging defense committees as autonomous revolutionary bases for future-oriented struggle. They were meant to embody a “microcosm of the society that we’re trying to build.” The committees, in other words, would provide concrete examples of the new society being created inside the shell of the old. Months after his release, the Potsdam group renamed itself the North Country Defense Committee and began a decades-long struggle against the construction of a high-voltage power line in the region. Sostre soon visited and they began discussing buying land and establishing food and book cooperatives. Although these collaborations did not come to fruition, the NCDC continued direct actions and community organizing in opposition to the power line. After Andrzeja Dubinsky of the Potsdam committee was arrested for standing in front of a dump truck to prevent construction on the power line, she wrote that there was “a person who helped me get involved again—made it absolutely impossible for me to remain silent. Martin Sostre.”

Sostre’s resistance to dehumanizing sexual assault was filled with frustration and dejection as well as violence. He later recalled being one of the only people in prison refusing them. “There was never at one time, more than four [people] resisting the rectal examination,” he said. “Four out of two thousand. You can see what the odds are.” But his refusals nevertheless catalyzed a movement that secured his release from a de facto life sentence. They had also brought dozens of others into broad-based struggle against the oppressive state. Many whose initial defense of Sostre came from what they perceived to be the extreme injustice of his case—the frame-up, the state’s assaults, its tactics of legal obstruction—later came to understand it as illustrative of something far more fundamental. They began to see the prison as he did: a concentrated form of broader, oppressive forces.

Sexual assault in the form of pat downs, strip searches, and other violations of bodily sovereignty remains a routine act of violence in prisons, jails, and other forms of detention today. Over the last twenty years, New York City has paid over $70 million to settle lawsuits addressing strip searches at Rikers Island and other jails. These assaults especially affect Muslims, women, people of color, and queer and trans folks. The Supreme Court has repeatedly refused to protect the bodily autonomy of imprisoned people under the Fourth Amendment. Corey Arthur, who has been incarcerated in New York since 1997, estimated that he has been strip searched over a thousand times since his first assault by two police officers when he was fourteen. When I mentioned Sostre to Arthur, he immediately recognized Sostre’s legacy of resisting such assaults and their significance to him. At a youth prison in Illinois, a group of teenagers studying Sostre have begun resisting pat downs when leaving their unit, inspired by his example.

Still largely unknown to the public, Sostre’s resistance to state-sanctioned sexual assault remains alive in prisons through oral tradition and radical political study. It offers us crucial lessons in understanding the relationship between the routinized violence of the state and our own movements for abolition, bodily sovereignty, and a classless society. As Sostre argued, “the struggle for liberation begins with the individual whenever and where she or he is oppressed.”

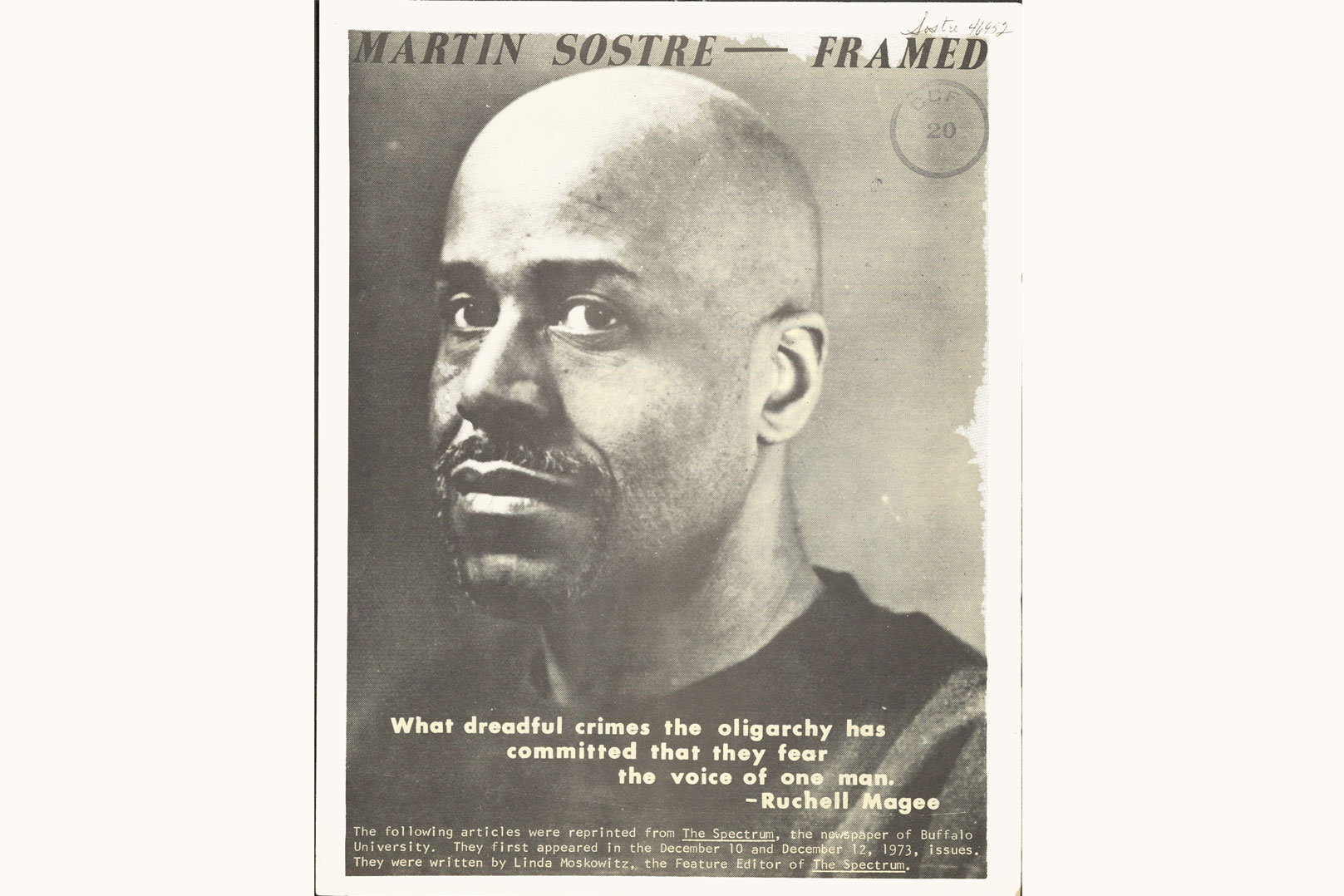

Header image: Poster of Martin Sostre, featuring a quote by political prisoner Ruchell Magee. (Courtesy image.)