A little over a month before the murder of George Floyd, police officers in Tucson, Arizona, killed Carlos Ingram Lopez, who was going through an apparent mental health crisis at the time of his arrest. Handcuffed, naked, with a hood and two plastic bags over his head, Ingram Lopez was restrained by at least two officers while he begged for water and his grandmother for 12 minutes, slowly asphyxiating to death. All the officers involved were cleared of wrongdoing. More recently, in San Antonio, police officer James Brennand shot 17-year-old Erik Cantu multiple times over the crime of eating a hamburger in his car. The officer claimed that he thought the car was stolen and alleged that Cantu had attempted to flee. Brennand was fired and now faces a criminal indictment. Cantu endured multiple surgeries and spent more than a month in the hospital and was later readmitted, but he survived the encounter.

These are but two cases that are analogous to more well-known cases of Black people killed by police. The public knows of Floyd, Tamir Rice, and many others. But do they know of Mario Arenales Gonzalez and Andy Lopez? How about Pedro Erick Villanueva? The similarities between the police killings of African Americans and Mexican Americans and other Latinos are breathtakingly horrible — and, sadly, just as unjustified. Yet these police killings do not generate nearly as much coverage or national outrage. This might lead some observers to think that Mexicans, Mexican Americans, and other Latino people don’t have the same kind of policing history that other ethnic groups do. I wrote Borders of Violence and Justice: Mexicans, Mexican Americans, and Law Enforcement in the Southwest, 1835-1935 to provide some of that history.

The book actually has a fairly long origin story. Like any author, I wrote it for many reasons. The project started in 2005, when I ran into the case of Santos Rodriguez, a 12-year-old Mexican American boy executed by Dallas police officer Darrell Cain on the night of July 24, 1973. At the time, few people knew about the case. Cain used a game of Russian roulette to try to extract a confession from Rodriguez for a petty offense he didn’t commit, ultimately shooting him in the head in front of David, the boy’s brother. To me, Santos was emblematic of the complicated relationship between Mexican Americans and police: He was apprehended by an agent of the state during an ostensibly legal and legitimate process, but that process quickly veered into extra-legal and patently illegal territory. Like any project of this scope, my research took me in directions I did not expect. It also took me far back in time — back to the 1830s, which ultimately meant that I would need to write two books instead of one. Borders of Violence and Justice is the first.

Borders examines interactions between Mexican-origin people and law enforcement — police agencies as well as extralegal lynch mobs — across the Southwest from the 1830s to the 1930s. Beginning with the Texas Revolution in 1835 and later the Mexican American War, the United States annexed the Southwest via military might. U.S. forces quickly established law enforcement as well as extralegal groups to maintain state power in the region. Police and their allies often treated Mexicans and Mexican Americans as a population that they deemed suspect and undesirable. Popular sentiment, much like in segments of U.S. society today, also construed Mexican-origin people as criminally prone, as violent, and as wanton murderers. Many of these viewpoints were outgrowths of white supremacist concepts such as Manifest Destiny. While egregious and wrong, these ugly beliefs and this sense of superiority meant that law enforcement tended to abuse their authority and treat Mexican people and their kin brutally.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

Mexican-origin people responded to this legal and extralegal violence in a variety of ways. For example, they defended themselves and fought back when confronted by racist law enforcement. They formed self-defense groups and advocacy organizations to protect themselves. Some became police officers to respond proactively to violence and to defend Mexican people. Mexican Americans also pushed state and territorial governments to professionalize law enforcement to halt abuse. They could also lean on the Mexican government for assistance — a type of aid that other ethnic communities often did not have.

My book is filled with stories that typify this complicated and often violent history. But the one case that brings it all together — law enforcement’s brutality, extralegal tactics, the abuse of authority, Mexican American police officers, and the response of the Mexican government — was that of Manuel Mejía. He was a well-liked, 32-year-old miner who had lived in Yavapai County, Arizona Territory, for about 15 years. The available public record suggests nothing that would justify his fate: Mejía narrowly escaped being lynched four times over.

In some ways, Mejía’s story resembles other instances of mob justice in U.S. history, but here’s the short of it: In August 1886, an unidentified person murdered Yavapai County store owner Barney Martin and his wife and two children. Law enforcement in Maricopa County had only the bloody bodies of the family and no suspects or leads. The Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office asked Mejía to assist them with an investigation into the murders. Deputy Sheriff J.W. Blankenship instead arrested Mejía, who spent 17 days in jail in Phoenix. When he was finally released, a mob of 10 men pounced on him. They dragged him to a cottonwood tree and strung him up, using multiple hangings in an attempt to force him to confess. When he refused, they hanged him a fourth time and left him to die.

Manuel Mejía did not die. Instead, as he explained in his post-lynching testimony, after the third lynching attempt he managed to free his hands and retrieve a knife from his boot. He then cut himself loose, ran, and escaped the mob. Phoenix Town Marshal Henry Garfias, one of the most important law enforcement officials of Mexican ancestry in the territory, aided Mejía. Working with Maricopa County District Attorney Frank Cox, Garfias attempted to secure justice for Mejía. At the same time, Mexican Envoy Matías Romero began putting pressure on territorial and federal officials to punish Mejía’s attackers. These efforts produced some results: The territory issued rewards for information, Mejía swore out a complaint against his assailants (many of whom he had recognized), and the county put them on trial. But the attackers successfully produced alibi witnesses, so the only evidence against them came from Mejía. As he explained, after a short hearing, “the Judge discharged my aggressors” because of a lack of evidence. Manuel Mejía never got his justice. Though he lived, he received lifelong injuries from his ordeal. As more information in the case came to light in the late 1880s, it became even clearer that he had nothing to do with the murder of the Martin family. Instead, he was simply a convenient scapegoat who was lucky to have narrowly survived a police force that abused its authority and a mob that wanted him dead.

The example of Manuel Mejía encapsulates almost every type of historical intervention I attempt to make in Borders. Its pages feature violent law enforcement officers who abused their authority, but also some good ones who did their duty and tried to set things right. It’s got extralegal justice masquerading as law enforcement. It’s got a Mexican-origin person who was wrongly accused of a crime and who suffered a horrific offense at the hands of individuals and the state. It has a community responding to this unspeakable violence in the best way they could and a concerned Mexican government that tried to help.

In many ways, the violence and lawlessness that Manuel Mejía endured are still with us today. Mexican Americans and other Latinos are more likely than white Americans to experience police brutality and the abuse of police authority. They are more likely to be killed by police. They are more likely to be racially profiled during traffic stops and other police encounters. They are more likely to be accused of a crime and convicted when not guilty or plead to a crime they didn’t commit. They are also more likely to receive the death penalty than white defendants and to be wrongfully executed for crimes they did not commit. We also know that extralegal justice still occurs. The massacre of 23 individuals, mostly Mexican or Latino people in El Paso in 2019, is illustrative. The murderer, Patrick Crusius, in a manifesto, railed against “Hispanic people” and claimed his “attack is a response to the Hispanic invasion of Texas.” The grieving families, for their part, are still awaiting justice the state has yet to provide.

Crusius’s reference to a so-called invasion is a canard that has its roots in the late 19th century, when Americans first began to fear the loss of American territory acquired from Mexico. Today, rightwing, nativist groups frequently talk up la reconquista as both a physical loss of territory as well as a loss of western cultural identity — a loss that has been prophesied for well over 100 years but has never happened. It’s a fantasy that implicates law enforcement because individuals like Crusius allege that “lax border security” is a failure of law enforcement. He mentions these supposed failures as the justification for his actions — a common theme in the violent history I discuss in Borders. But these failures are all fever dreams without any real basis in fact. They still have a great deal of potency for people who are susceptible to conspiracy theories, such as the unfounded belief that white people are at risk of being replaced by Latinos/as or other immigrant groups, which Crusius also alluded to and is a staple of rightwing talking heads and political actors.

My hope with Borders of Violence and Justice is that it will serve as a kind of course correction, speaking truth to the lies told about Mexican-origin people. The problems we see today — over policing, abuse of authority, state-sanctioned violence, overincarceration, punishment, and extralegal justice against historically marginalized groups — have a very long history. Understanding that long history is a first, necessary step for beginning the process of imagining a different future. For the sequel, I plan to continue exploring this history into the 21st century — to provide more concrete ways we might work to change how the criminal legal system treats Mexican Americans and, by extension, all Americans.

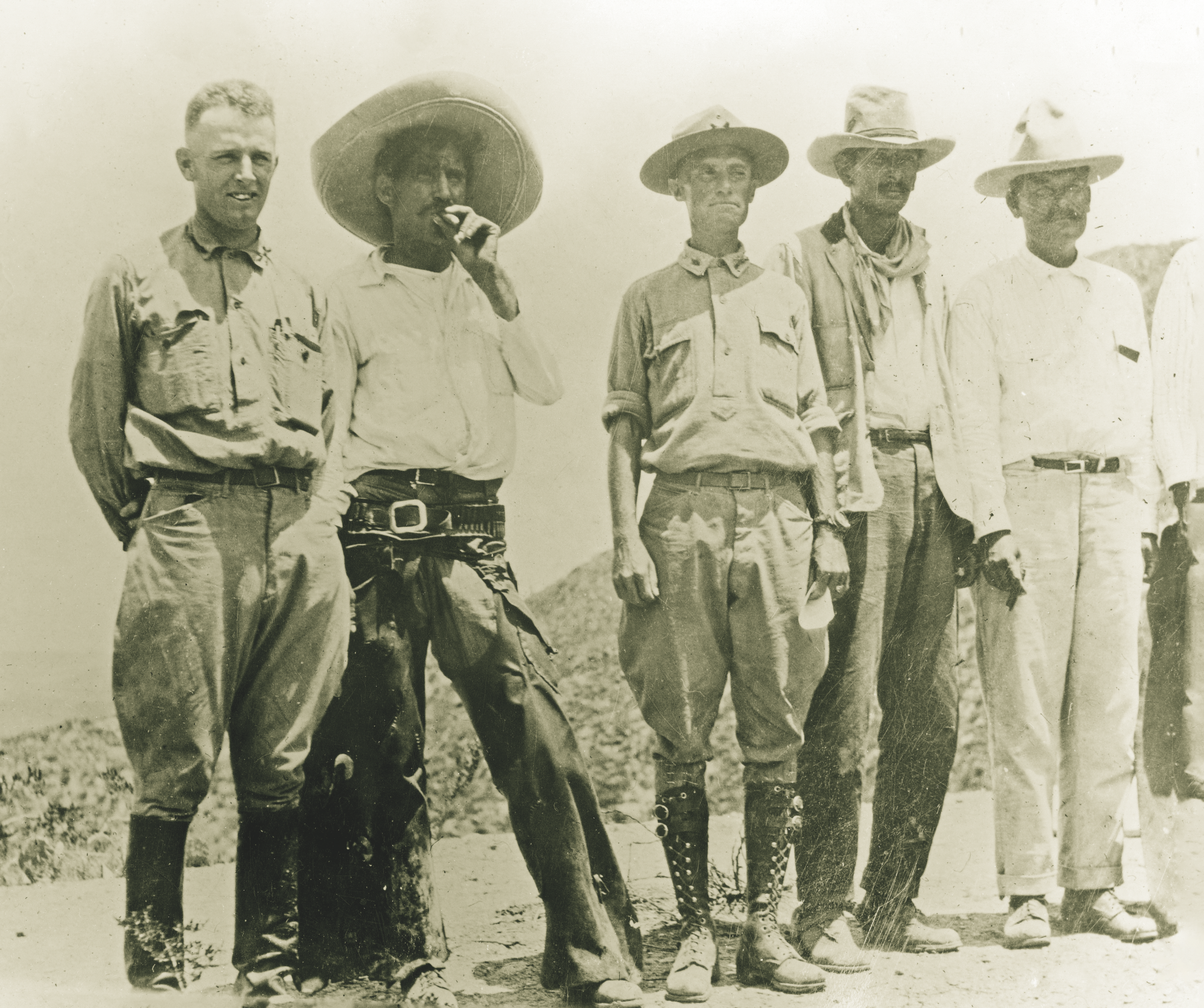

Header image: Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin.