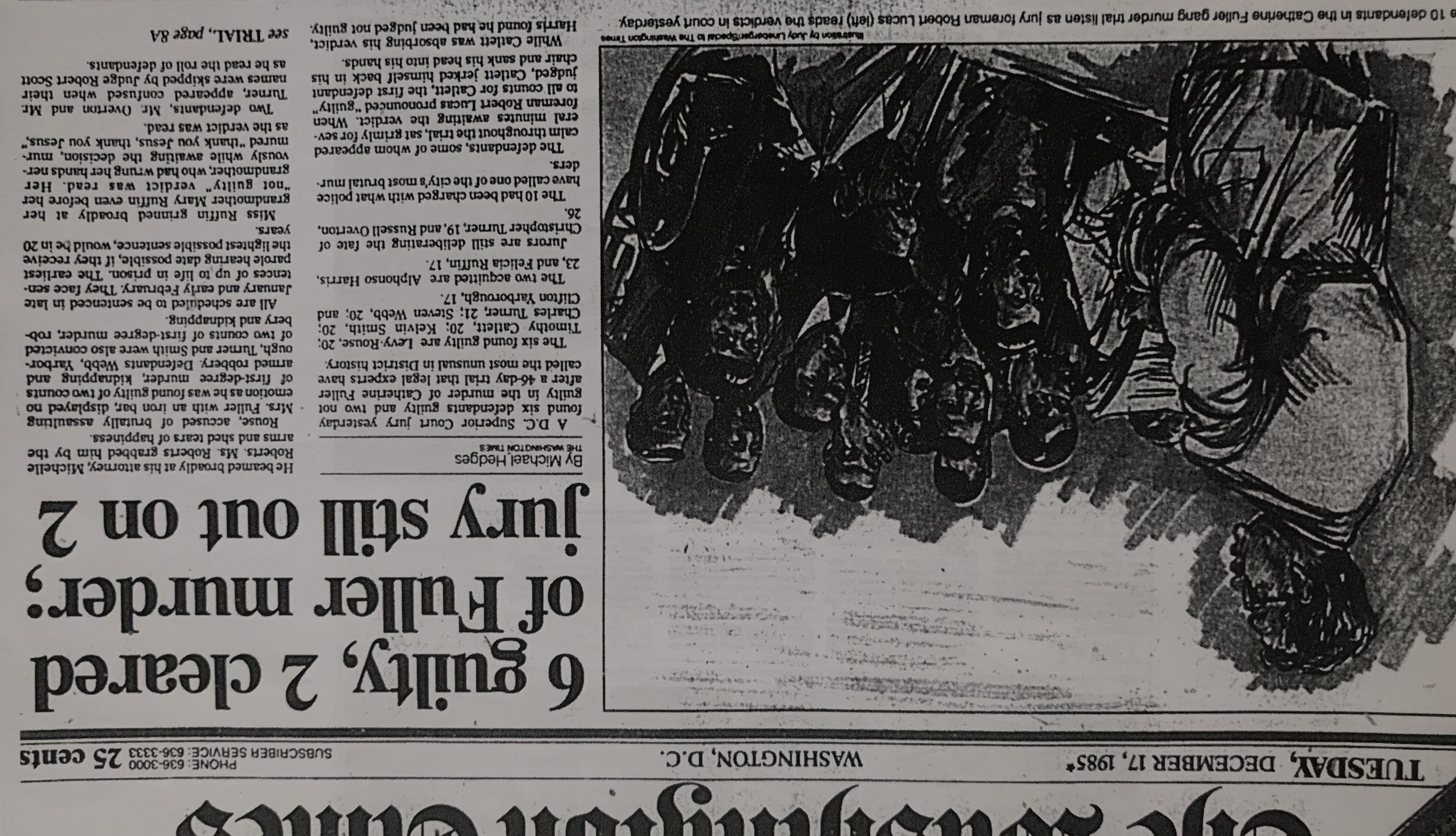

In the late afternoon of October 1, 1984, Catherine Fuller, a 49-year-old wife and mother of six, left her brick rowhouse in Washington, D.C., on a shopping trip. Barely 90 minutes later, a street vendor found her dead in an empty garage off a narrow alley near the corner of Eighth and H Streets NE. She had been robbed, beaten, and sodomized.

Police called it one of the most savage crimes in the District’s history, and detectives were under pressure to find a swift solution. Quickly, they crafted a theory from an anonymous phone tip: Members of a local gang had pushed Fuller into the alley to rob her. When she resisted, they had dragged her into the garage, attacked “like sharks on a feeding frenzy,” then left her to die. This theory soon became the official narrative.

Over the next six months, police charged 17 young people from the neighborhood with Fuller’s murder. But no physical evidence ever linked any of the defendants to the crime. Hundreds of interviews failed to turn up a single independent eyewitness who had seen anything related to a gang attack. The prosecution’s case relied on two teenagers who traded their testimony for leniency in their own cases.

In the fall of 1985, after a five-week trial and nine days of jury deliberations, eight young Black men were convicted for the murder, despite their protestations of innocence.

The defense lawyers didn’t know there was a very different—and highly plausible—crime story. That’s because the lead prosecutor, Jerry Goren, had hidden evidence of two other suspects, who together or separately may have committed the killing.

Under the Brady rule, adopted in 1963 the prosecutor’s wrongdoing should not have been possible. Brady requires that prosecutors in criminal cases disclose any evidence favorable to the defense. The rule was a grand idea. But it didn’t work in the Fuller case, or in untold thousands of other cases. It hasn’t worked, period.

The National Registry of Exonerations says hiding exculpatory evidence—breaking the Brady rule—is the leading cause of wrongful convictions. Of 2,400 documented exonerations between 1989 and 2019, Brady infractions helped to convict 44 percent—1,056 people. That we know about. Prominent legal scholar Bennett L. Gershman called the rule “a monument to judicial and ethical impotence.”

As a public defender in Washington, D.C., I saw prosecutors routinely violate Brady. And when they did, judges mostly shrugged. My book, When Innocence Is Not Enough: Hidden Evidence and the Failed Promise of the Brady Rule, tells the winding history of how the rule failed, anchored by the 39-year odyssey of the Fuller murder case. Together, the book’s narratives illustrate Brady’s potential, detail its demise, and point a way to making its promise real.

The Brady rule might never have existed if John Leo Brady hadn’t been in love. In the summer of 1958, at the age of 25, he fell for a married 19-year-old, who was soon pregnant with his baby. On top of this, Brady was broke. He decided the solution to his financial woes was to rob a bank. He enlisted his girlfriend’s older brother, Charles Donald Boblit, to help.

When the two men tried to steal a car for their heist, the owner resisted. Boblit panicked and killed the driver. They abandoned their robbery plan but were soon arrested for the murder. Each blamed the killing on the other, so they were tried separately, with Brady going first.

Before his trial, Brady’s attorney asked the prosecutor for copies of any statements Boblit had made to the police. Several were disclosed. But one was withheld: the one where Boblit admitted he had, in fact, done the killing himself.

After Brady’s conviction, his attorney learned of the additional statement and moved for a new trial. The case, Brady v. Maryland, eventually reached the Supreme Court. In a 7–2 decision written by Justice William O. Douglas, the court said due process requires prosecutors to disclose information that is “favorable to an accused” and “material either to guilt or to punishment.”

Douglas’s dream was that the Brady rule would help shift the criminal process from partisan combat to a mutual search for facts. But in hindsight, Brady was doomed from the start. The rule sought to impose a vision of fairness on a system that was unfair at its core. It was a fundamentally competitive process fueled not by the desire of prosecutors to pursue justice wherever it led, but to win convictions. Its primary aim was efficiency, not fairness. Realistically, no single judicial decision could transform this deeply entrenched system.

Two practical factors further weakened the capacity for Brady to create change. First, prosecutors still controlled the flow of information. They alone decided what to conceal and what to reveal. It was too easy, even in a high-profile matter, for them to hide evidence that might hurt their case. Second, the Brady opinion failed to spell out exactly what it meant for something to be “material” to guilt or punishment. Over the next two decades, the justices would struggle to devise a clear, workable definition.

Finally, in U.S. v. Bagley (1985), the Supreme Court settled for an outcome-based determination: Evidence is “material” if there is a “reasonable probability” that, had it not been withheld, “the result of the proceeding would have been different.” You don’t need a law degree to see how slippery this so-called definition is. It requires that a judge look back—often years or decades after a trial—and decide how some piece of evidence might have impacted the verdict. The standard is so subjective that almost any ruling could be justified.

And since courts love finality above all, and hate to reverse settled decisions, the results have been predictable. Faced with Brady claims, judges nearly always rule that, although hidden evidence might have been favorable, it isn’t material. No harm, no foul. A study by the Veritas Initiative found that, in a random sample of Brady claims litigated in federal courts from 2007 to 2012, 86 percent of the time the court excused the breach by saying the information wasn’t material.

Under these circumstances, Brady’s demise was inevitable. And the Fuller case is, sadly, a textbook illustration of what typically happens.

A few weeks after Fuller’s murder, a woman told police that she’d been in the alley behind H Street on October 1, shooting heroin. While there, she had seen a man she knew—not one of the accused—“beat the fuck” out of Fuller “for just a few dollars.”

In addition, two different witnesses—the street vendor who’d found Fuller and a friend of his—reported seeing two young men at the murder scene acting suspiciously; both young men had fled when the police arrived. The attendant and his friend even identified the men from police photographs; neither were among those charged with Fuller’s murder.

These alternative suspects didn’t fit the prosecution’s theory. If one or both had killed Fuller, the official narrative they’d come up with—that the killing had been committed by a gang of neighborhood youth—was wrong.

Goren, the lead prosecutor, was in a bind. After making 17 arrests—and after proclaiming the crime to be solved—he was all in on the gang story. He also knew his case was thin. It rested on two snitches with sweet plea deals. Disclosing evidence of these other suspects would give the accused a defense far stronger than the flimsy alibis they had put forward. He might lose the biggest trial of his life.

So he hid this Brady evidence. The result was that eight men who had nothing to do with Catherine Fuller’s murder spent a total of 255 years in prison for the crime.

The information about the other suspects would likely have stayed hidden forever without the work of Washington Post reporter Patrice Gaines. In the mid-1990s, she and a colleague began to dig into the old files and interviewed many of the Fuller case participants. In 2001 she published an article articulating her concerns about police and prosecutorial misconduct. Because of her work, the Mid-Atlantic Innocence Project (MAIP) agreed to take on the case.

Lawyers working with MAIP uncovered the evidence of the alternative suspects the prosecution had withheld, along with new information that further undermined the gang theory. This led to a new round of appeals for the men which, in 2017, went all the way to the Supreme Court. There, the majority of the justices deemed that the Brady evidence was “too little, too weak, or too distant from the main evidentiary points” to meet the materiality standard.

The two dissenters (Justices Elena Kagan and Ruth Bader Ginsburg) argued that the evidence of alternative perpetrators would have changed “the whole tenor of the trial,” and “could well have flipped one or more jurors—which is all that Brady requires.” But 33 years after the fact, that was a hard claim to prove. The convictions stood.

What happened in the Fuller case is too common. Sometimes prosecutors don’t recognize Brady material, or don’t know about it. But many times, they simply fear losing, as Goren did. They convince themselves they’re promoting justice by hiding evidence. It’s simple to do. And as long as prosecutors control all the case information, it will keep happening.

The repeated disregard for the Brady rule is a clear indictment of our criminal legal system, and a disturbing reminder that it is not designed for justice or fairness. But even within that system, we can—we must—make changes that will mitigate harm for real people experiencing it in the here and now, undertaking what Mariame Kaba and others have described as “non-reformist reforms.”

In my book, I argue that one viable path is to implement the intent of Brady through legislation; to take disclosure decisions out of the hands of prosecutors and impose open-file discovery by fiat. The good news is that we already know how to do it. Two unlikely places—North Carolina and Texas—have shown the way.

In each state, after an egregious Brady violation led to a well-publicized wrongful conviction, state legislators passed a law requiring prosecutors to open all their files to the defense early in the process and enforced that obligation with strong sanctions. Following some initial modifications, those laws have proven to be surprisingly successful at satisfying the intention of Brady.

Open-file discovery is not a magic bullet, nor is it an instant solution. But it’s workable and effective. Restrictive disclosure laws have helped put thousands of innocent people behind bars. If we care about justice, it’s past time to bury the Brady rule, and make open-file discovery the law everywhere.

Image: Thomas Dybdahl/Inquest