If you’re of a certain age — the last of the boomers or the first cohort of Generation X — and grew up Black and urban, you may have a tendency to romanticize the cops who used to walk the beat. The boys in blue who knew everyone in the neighborhood. Truth be told, the officers I most remember from my years growing up in the South Bronx were white do-gooders who appeared on TV in the 1970s. Back then, I was oblivious to the criminalization of Black bodies, the anti-Black violence that was propagated by the law enforcement community writ large, or the ideological framing about who and what the police were. I was unaware of the copaganda that pop culture had served up to an unsuspecting public for generations.

Copaganda — the reproduction and circulation in mainstream media of propaganda that is favorable to law enforcement — has long been a tool to disrupt legitimate claims of anti-Black violence. Simply put, copaganda actively counters attempts to hold police malfeasance accountable by reinforcing the ideas that the police are generally fair and hardworking, and that “Black criminals” deserve the brutal treatment they receive. Such cultural framing has been critical to buttressing the need for a more expansive criminal justice system that fuels mass incarceration.

When I was a kid, my father worked six days a week, twelve hours a day. He spent his downtime listening to gospel quartets and watching police and private detective dramas that played in the NBC Mystery Movie programming rotation: shows like McMillan & Wife, McCloud, and Columbo. I suppose that my father, a Black, undereducated, working-class man from the South, was drawn to the kind of folksy, down-home characters featured in these shows, in part because he found them to be comforting as examples of respectability that would be available to his young son.

Simply put, copaganda actively counters attempts to hold police malfeasance accountable by reinforcing the ideas that the police are generally fair and hardworking, and that ‘Black criminals’ deserve the brutal treatment they receive.

The shows were often comical and pivoted on innocuous notions of morality, where “good” always won out over “bad” (the criminals were rarely “evil” on 1970s television in the ways that so-called Middle Eastern “terrorists” were portrayed in the 1980s). McCloud, for example, was a fish-out-of-water detective from the Southwest who brought his style of policing to the “big city” (he’d often chase “criminals” on horseback). Columbo, which aired intermittently for more than three decades, hinged on the “genius” of a dusty, rumpled gumshoe who constantly looked as if he’d just fallen out of bed to solve a case.

While those shows endeared law enforcement to the public, other programming from the era was more intentional in its messaging. Another staple on my dad’s television was The F.B.I., a show that saw actor Efrem Zimbalist Jr. — a Goldwater Republican — acting out scripts vetted by the actual FBI, which in real life was laying waste to a generation of Black freedom fighters and their organizations. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover architected COINTELPRO, which used various forms of disruption, including infiltration and violence, to undermine civil rights, Black liberation, anti-war, Native, and white radical organizations. Hoover famously identified the Black Panther Party as the biggest threat to American society. The F.B.I. was monumental in swaying the public at a time when “law and order” was a rallying cry.

I also enjoyed watching the short-lived series S.W.A.T. (the inspiration for the 2003 Samuel L. Jackson film of the same name) and syndicated episodes of Adam-12, both of which were set in Los Angeles. No more than ten or eleven years old at the time, I fancied myself as S.W.A.T.’s Dominic Luca (Mark Shera) and rookie officer Jim Reed (Kent McCord) from Adam-12. Little did I know that the SWAT (Special Weapons and Tactics) unit had been designed in the mid-1960s by Los Angeles Police Department inspector Daryl Gates in the aftermath of the Watts Riots of 1965.

Intended as the police force’s militarized arm that could address volatile situations that needed quick and potentially violent resolution — such as snipers and the taking of hostages — SWAT teams became a means to address urban protest. Not surprisingly, one of the first uses of SWAT was an attack on the Black Panther Party’s LA headquarters in December 1969, in which more than three hundred officers took on thirteen Black Panther members (more than half of whom were women and children). The attack occurred only days after a similar police raid in Chicago that killed Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, in what poet Haki Madhubuti called a “one-sided shootout.” Both incidents highlight the close relationship between local law enforcement and the FBI during the period.

The show Adam-12 featured the Rampart Division of the LAPD, which, two decades after the show’s debut, would become the basis of a police corruption case involving the Community Resources Against Street Hoodlums (CRASH) unit. Also conceived of by Gates, CRASH intimately connected to the police brutality narratives heard in gangsta rap of the late 1980s and 1990s in songs like Toddy Tee’s “Batterram” and N.W.A’s “Fuck the Police.” In the case of CRASH, the narrative of urban radicals had shifted to concerns about the “war on drugs” during an era when crack cocaine was being introduced to Black and Brown urban communities. Aside from the examples in rap music, most Americans were unaware of these efforts until the release of the 1988 film Colors, in which Robert Duvall and Sean Penn portrayed CRASH officers.

The irony was that the affable Dominic Luca and Jim Reed of the shows S.W.A.T. and Adam-12, respectively, were the public faces of the LAPD in an era in which its figureheads like Gates — who became the very symbol of racist policing in the post–civil rights era — were creating apparatuses that would have dramatic and traumatic impacts on Black communities for decades. These contradictory realities speak to how palpable copaganda was as a resource to influence public opinion and thus public policy regarding law enforcement.

With the exception of the ensemble casts of the sitcom Barney Miller and the melodrama Hill Street Blues, Black officers were largely missing as primary characters in the narratives of the ’70s and ’80s, a dearth that reflected the lack of diversity in station houses in the period. Charles Barnett’s 1994 film The Glass Shield, for example, fictionalized a real-life attempt to integrate a Los Angeles area sheriff ’s office. Black novelists filled in the gaps, though. Chester Himes’s Harlem Detectives series featured Grave Digger Jones and Coffin Ed Johnson, two detectives who became more prominent when they were depicted by Godfrey Cambridge and Raymond St. Jacques, respectively, in 1970’s Ossie Davis–directed film Cotton Comes to Harlem and Come Back, Charleston Blue two years later.

In Raymond Nelson’s 1972 essay on Himes’s detective novels, he describes Grave Digger and Coffin Ed as “bad niggers” — symbols of “defiance, strength, and masculinity to a community that has been forced to learn, or at least to sham, weakness and compliance.” And indeed, on-screen, Cambridge’s and St. Jacques’s performances of the duo were given the gravitas of “race men” — these figures, often men, within Black life and culture who were committed to the “race”; they didn’t simply acquiesce to the white power structure that employed them but also offered a healthy skepticism of ghetto hustlers while using their badges and relative privilege to look out for the “least of” in Black Harlem. The extent to which Grave Digger and Coffin Ed were depicted as being embedded in the very fabric of Black Harlem was a refreshing counter to the drive-by treatments of Black life found in most film and television in the era, particularly with regard to law enforcement.

The 1991 film A Rage in Harlem, a third of Himes’s detective novels to be adapted for the big screen, found Grave Digger and Coffin Ed on the periphery of the film’s focus, as if it were a metaphor for the cultural shifts that had seemingly occurred in the previous two decades. In many ways, Grave Digger and Coffin Ed were precursors to the Black-White cop buddy films of the 1980s — think Danny Glover and Mel Gibson in Lethal Weapon, or 48 Hours, in which Eddie Murphy played a petty criminal working with a detective (Nick Nolte). Whereas the idea of cop buddy films with two Black actors was not tenable to Hollywood at the time — and would not be until the Bad Boys franchise — the Black-White cop buddy films were more marketable given the success of films like The Defiant Ones (Sidney Poitier and Tony Curtis) and the Richard Pryor and Gene Wilder films of the 1970s and 1980s.

Notable about these films, including the Bad Boys franchise with Will Smith and Martin Lawrence, is the way that Black officers were largely evacuated from Black life and community. Though Glover played a family man in Lethal Weapon, there was nothing inherently Black about his life. (In fact, Gibson played the role of the rogue cop.) This could also be seen in the television series NYPD Blue, where James McDaniels portrayed Lt. Arthur Fancy for the series’ first eight seasons, yet there was little attention to his life outside of the precinct. The Law and Order franchise reveals little about the backstory of numerous Black officers played by the likes of Jesse L. Martin, Anthony Anderson, and Ice-T, who has portrayed Sgt. Odafin “Fin” Tutuola for nearly twenty years.

The aforementioned fictional officers exist in contrast to Boyz n the Hood’s Officer Coffey, a Black cop (played by Jessie Lawrence Ferguson) whose disdain for Black youth is palpable. Denzel Washington’s Oscar-winning performance as Alonzo Harris in Training Day is yet another example of a character who is allowed to reign terror on a Black community due to the faulty logic of Black-on-Black crime and the benign neglect directed toward poor and working-class communities of color that renders those communities as complicit in their own pathologies. In such instances, it seems Black people and other marginalized communities do not deserve to be protected and served.

In much of popular culture Black officers are no longer race men at all — but, rather, stand-ins for the very anti-Black violence directed at Black communities.

That such characters were featured in films by Black directors (John Singleton and Antoine Fuqua, respectively) doesn’t change the fact that in much of popular culture Black officers are no longer race men at all — but, rather, stand-ins for the very anti-Black violence directed at Black communities. As a whole, these characters are complements to the purposes of copaganda, serving as examples of Black exceptionalism on the one hand while suggesting that policing is race-neutral but criminality is not. In fact, such characters help valorize and legitimize both the extra-policing and extrajudicial forms of violence directed at Black bodies. Yet the more things change, the more they stay the same. Those beat cops on Adam-12 that I once idolized as a kid now sit comfortably around the Sunday dinner table as three generations of officers on the police drama Blue Bloods. Thoughtful, introspective, and devoted to God, family, and the law — who wouldn’t want them to protect and serve?

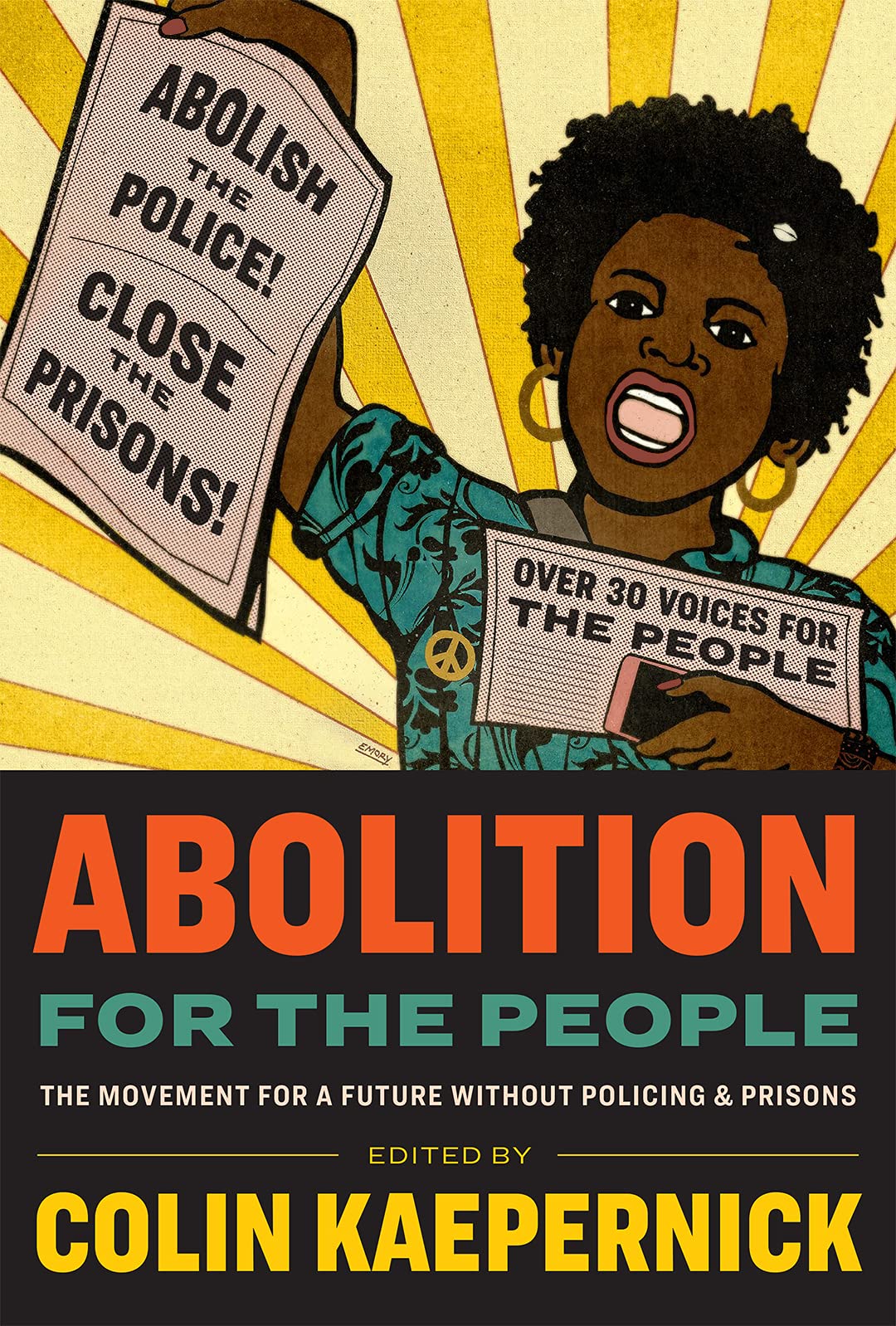

From Abolition for the People: The Movement for a Future Without Policing & Prisons, edited by Colin Kaepernick. Used with permission from Kaepernick Publishing.

Image: Unsplash