To live in the United States is to be aware of the high levels of interpersonal violence in everyday life. Far less often do we acknowledge the prevalence of state violence. On the rare occasions when the nation turns its attention to atrocities such as George Floyd’s murder by police, the public discourse around state violence tends to occur separately from conversations about street violence in our neighborhoods or family violence in our homes. Seldom do we examine the causal relationship between them all, recognizing and discussing the ways that state violence, inflicted as punishment, is deeply tied to the violence that happens in communities.

For the last two years, the Justice Beyond Punishment Collaborative in New York has come together to challenge carceral punishment and advance community-based mechanisms for safety and justice. Our work is rooted in naming, exploring, and addressing the interconnection between state and community violence.

The origins of Justice Beyond Punishment are intimately tied to the work and legacy of the late Kathy Boudin, who cofounded the Center for Justice at Columbia University and codirected it for nearly ten years before her death. Kathy spent twenty-two years incarcerated for her participation in an armed robbery connected to the Black Liberation Army and the Weather Underground, in which three people were killed. Throughout her time in prison, Kathy was committed to the work of justice, building communities of care and healing.

Kathy took seriously the dominating and totalizing violence of the state, while refusing to turn away from the devastation that comes from the violence people commit against one another. When she got out of prison, her work focused both on challenging the harms of state violence and getting people out of its grip, which inspired her to cofound Release Aging People in Prison (RAPP Campaign), as well as supporting people still inside in their own growth and transformation—including in coming to terms with the violence they had committed. Coming to understand the relationship between these two forms of violence became a central goal.

For Kathy, community and collectivity were both the method and the means, so creating a collaborative of diverse voices was an obvious approach to the work.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

The Justice Beyond Punishment Collaborative is made up of activists, organizers, academics, lawyers, and educators who hold a range of identities and experiences, including being formerly incarcerated, queer, and immigrant. Many also identify as survivors or as people who have caused harm—sometimes both. Our backgrounds include survivor-led work, violence interruption, anti-racism and gender justice, parole and drug policy reform, as well as healing justice, transformative justice, and restorative justice.

We chose narrative change as a focus of our work to end state and interpersonal violence because the current punitive narrative works so powerfully against the world we believe we can build. This narrative holds that state punishment is the best, most effective response to interpersonal violence. Against a wealth of evidence to the contrary, this carceral narrative keeps current practices firmly in place. This is especially true in New York state, where local news constantly bombards the public with skewed images and stories that demonize those accused of violence—particularly Black men—and unflaggingly glorifies carceral responses.

Yet we believe we can take back this narrative—by shifting it ourselves. Narrative change is a growing field in which activists, organizers, storytellers, media makers, and many others first understand and then reshape the deeply held stories and messages in our culture that create the basis for how we see, understand, and respond to the world. As Ai-jen Poo and Eldar Shafir of the U.S. Partnership on Mobility from Poverty have written, “Narrative change is not about . . . changing which news reports get broadcast.” Instead, “narrative change is about reworking the stories that come to mind after we hear that news” and “about rerouting the path between what we hear and how we make meaning.” Making new meanings of the world people see and hear is how we hope to drive change.

When so many stories and messages have been so deeply ingrained for such a long time, rerouting our path to meaning is hard won. For example, social change activists generally agree that the dominant narratives in the United States about who is deserving of safety, care, and justice are steeped in white supremacy and racial capitalism. Yet many in our movements struggle with identifying and ultimately denouncing these narratives whenever people who have committed violence are criminalized. Despite a recognition that mass punishment in the United States is heavily racialized, many believe those who have committed violence should be punished by that same racist carceral state.

Our collaborative’s hope is that focusing on narrative change would not only create the basis for lasting progress, but do so in a way that gets to the roots of racialized punishment and gives us a chance to develop new stories about what equitable justice means and looks like when we are confronted with violence of all stripes.

We take inspiration from groups who have laid the groundwork for confronting all forms of violence, like those from the movement for prison abolition—groups like Critical Resistance and Interrupting Criminalization—as well as the anti-carceral feminist struggles within the anti-violence movement, as advanced by groups like INCITE! and Creative Interventions. We also take inspiration from, and hope to build with, coalitions around the country working to build collective people power, like Californians United for a Responsible Budget and the People’s Campaign for Parole Justice in our own state of New York.

For more than two years, the collaborative has worked to develop a shared understanding about punishment, violence, safety, and justice and to strengthen our narrative change skills and strategies. Our process surfaced the tensions where we did not agree, bringing us face to face with the complex emotions and deep personal investment the dominant narrative fosters in each of us about what causes and drives violence, the in/effectiveness of punishment, and how we can achieve whole and safe communities.

Individually and collectively, we came to grips with the possibility of accountability and healing without incarceration and state-inflicted violence. Through these conversations, the connection between interpersonal and state violence became undeniable. Stories emerged that directly linked carceral violence to protracted physical violence as well as violence in the forms of truncated education, food and housing insecurity, destruction of progressive movements, medical and mental health injury, severe isolation, and ignoring and compounding unaddressed trauma. These root causes can drive people to commit violence, whether out of desperation or in response to trauma, leaving them vulnerable to further victimization.

This process resulted in three foundational pillars:

- Mass incarceration and carceral punishment are forms of violence, often referred to as state violence.

- Mass incarceration and carceral punishment do not make us safer or prevent interpersonal violence. Instead, they promote interpersonal violence.

- We need to elevate and grow community-specific and community-based approaches to address interpersonal violence that prioritize safety, healing, and accountability.

Our ongoing work lives in the tensions and questions prodded into being by these pillars. Our job became to create narratives that offer answers; address people’s emotional need for safety and justice; and, in the process, disrupt old narratives. Our primary audience is people in or adjacent to justice movements—people who may be open to thinking differently about justice and punishment. Because that audience is so diverse, and because we are trying to engage both emotion and intellect, we want to share our narrative in various styles and through varied media forms.

One of them is theater. We commissioned writer-director Kirya Traber to create Beyond Punishment: Stories of Justice and Healing, an original, interview-based theater production that follows the lives of four people who grapple with the intersections and impacts of interpersonal and state violence—and explore what it means to embrace accountability. This production, performed by the storytellers themselves, gives insight into their lives, leadership, and healing journeys, encouraging us to imagine justice beyond a punitive system that begets further violence.

Chi” Absolam performing Beyond Punishment: Stories of Justice and Healing on Dec. 1, 2023.

Another one is a soon-to-be-released podcast series. In The Problem with Punishment podcast, we talk to a cross-generation of New Yorkers from various walks of life to explore with them why turning to punishment for everything is a problem—and what can be done instead. More than anything, we want these conversations to be a resource for listeners to imagine ways to solve problems without resorting to carceral methods, and to get them to challenge how and why punishment is the only thing society has to offer for just about every aspect of our lives.

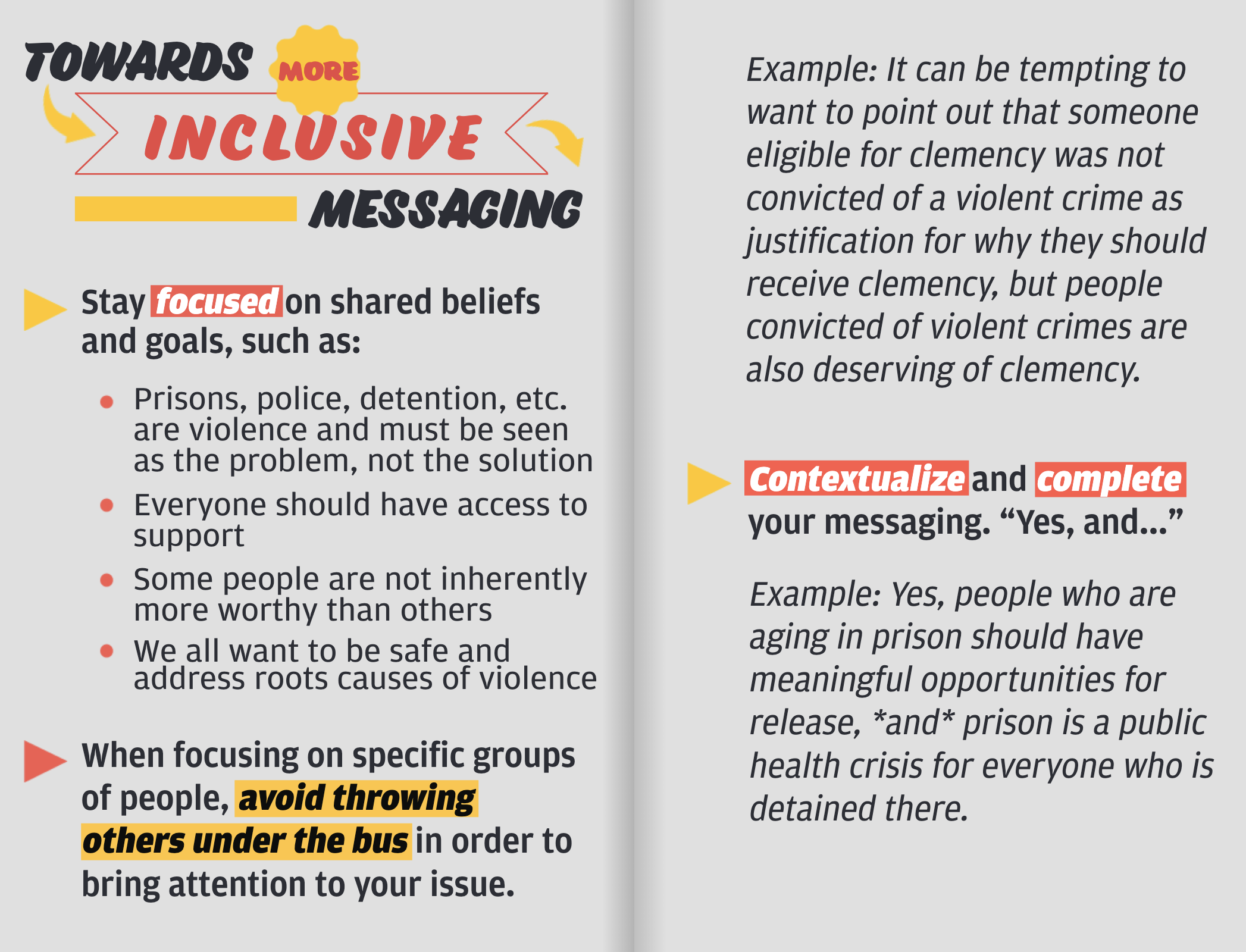

We’ve also created the Freedom for All zine. This publication emerged from a working group within our collaborative that looked at how well-intentioned advocacy efforts often create binaries or hierarchies of worthiness. By separating people into “deserving” and “undeserving,” advocates tend to engage in messaging, policy demands, and legislative concessions that end up leaving others behind. The goal of the zine is to explore the harmfulness of this approach—not just for our movement, but also for marginalized people whom the state already oppresses and others.

And, last but not least, we’re doing messaging work and offering political education. For messaging, we’ve engaged the communications experts at Change Consulting to help us boil down and strategically deliver the key points we want to share and amplify within our larger communities. And for organizations in New York City working on issues of violence, safety, justice, and punishment, we’re offering an introduction to the pillars of Justice Beyond Punishment, as well as an invitation to join us in moving away from punishment paradigms and toward ending all forms of violence.

We believe that the bulk of the work lives in our third pillar. The reasons for this have much to do with the power of the current carceral narrative.

Scenarios in which people call for punishment as necessary for justice, accountability, and healing lend themselves to story and narrative. I want someone punished because I care about their victims, someone might say. What could be a more satisfying equation than justice equals punishment, particularly when there’s an entire state apparatus ready and able to bring that punishment to fruition? Even if that sort of justice isn’t available (perhaps because the suspected wrongdoer has evaded the police) the idea of hunting them down is itself powerful.

It is far more difficult to name—and tell stories about—what should happen instead. This is especially true in an environment poised to reject non-carceral options. We know from our own families and communities, as well as from research conducted by the Center for Justice Innovations and others, that when people see harm done by family members or other loved ones, they will often take matters into their own hands rather than involve police, prosecutors, or the courts.

But these stories of family and community responses to violence, even when supported by community organizations that advocate for family safety or violence interruption, are often tightly held secrets. It goes against the norm—and, in many cases, against the law—to not call the police when harm occurs. Secrecy, or lack of public awareness, thus becomes yet another barrier to openly discussing viable options for alternative responses to violence.

Yet New York is a place where more just options do exist. The city is home to groundbreaking groups that practice community-based, community-specific approaches to addressing and reducing violence. These groups center safety and support for survivors as well as community accountability, while offering those who have been harmed options outside of carceral systems. A few examples are:

Community healing prevention / intervention:

- Collaborative for Restoring Healing and Transforming Communities in NYC

- CONNECT NYC!

- Girls for Gender Equity

- H.O.L.L.A!

- Common Justice EverAfter Project

Violence interruption:

- Community Capacity Development

- Street Corner Resources

- Kings Against Violence

Supporting people impacted by violence and those who cause harm:

- The Violence Interruption Project (VIP)

- The Anti-violence Project (AVP)

We decided to focus on the movement ecosystem in New York state to build community among the groups and organizations who could learn and grow together. Collectively, we can develop the infrastructure necessary to step more boldly into this new territory. We also know that New York is a blue state with a very mixed record on criminal justice: From bail reform and parole justice to the multiyear struggles to close Rikers Island and to pass and then enforce the Humane Alternatives to Long-Term Solitary Confinement (HALT) Act, progress has been hard to come by. Yet these stepping stones have been instrumental to building a movement in New York—one that is building shared commitments to lasting and equitable safety and justice, rooted in dignity and self-determination of all peoples.

We believe that if we can make a dent in New York, our work could have legs elsewhere.

Shortly before she came home from prison, Kathy wrote about the ways in which her own remorse shaped her belief in a different world:

Strangely enough, remorse also contains hope. In prison, we—probably more than most people—look over our shoulders at the past with regrets, questions, and sadness. But I must also have faith that I do not have to be frozen in my wrongdoing. The past and present are always circling into each other, yet always containing the possibility of moving forward.

Through her words and organizing, Kathy shared what it looks like to live the possibility of accountability and healing without punishment. This is the energy, faith, transformation, and forward movement we want our work to foster.

Header image: Chris Turgeon/Unsplash