In September 2021, Michael K. Williams was found dead in his home after overdosing from a mixture of heroin, cocaine, and fentanyl. Throughout his life, Williams openly shared his personal experiences with substance use and helped to challenge the stigma of addiction that continues to pervade so many of our national conversations around the overdose and other public health crises. The actor, best known for his role as Omar Little on The Wire, saw the interconnected roots of so many of our country’s harmful institutions and also fiercely advocated to end the harms of our criminal legal system.

Federal prosecutors charged the four men accused of selling drugs to Mr. Williams with conspiracy, which carries a mandatory minimum sentence of five years in prison. But Irvin Cartagena, the man whom prosecutors accused of physically handing the drugs to Mr. Williams, also faces an additional punishment for the act of causing the actor’s death. When illicit drug distribution “results” in death, Congress has empowered prosecutors to enhance the penalties for the initial drug conspiracy charge, which can carry a mandatory minimum of 20 years and a maximum of life imprisonment. Such “drug-induced homicide” charges, as they’re known, do not require the finding of intent to cause harm, much less death — only that the latter “results” from the drug use.

This specific case is attracting extensive popular attention, but it is far from unique. Faced with surging rates of drug-related deaths, government officials at all levels have grappled with what solutions make the most sense. Damian Williams, the United States attorney who announced Mr. Cartagena’s charges, even conceded that what we’re facing “is a public health crisis.” Yet despite all the evidence, and despite the reality that these laws and prosecutions create more harm, expanding the number, scope, and deployment of drug-induced homicide laws has become the de facto approach to this public health issue — while the actual, proven life-saving responses are ignored or dismissed.

Mr. Williams’ memory and that of those who continue to perish under the status quo demand that we change course.

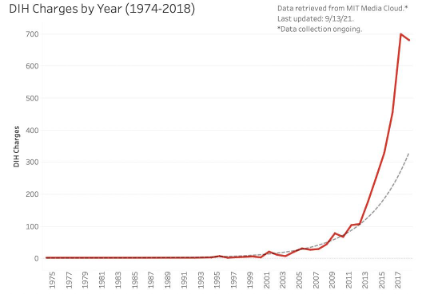

As used by prosecutors and reproduced in news accounts, “drug-induced homicide” broadly refers to a criminal offense in which the illegal manufacture, sale, distribution, or delivery of a controlled substance, when the controlled substance in question causes death, results in a specific charge, usually manslaughter or murder. The government’s prosecution of drug-induced homicide, or DIH, charges has exploded since its emergence in 1975. Like other carceral responses from that period, it is an outgrowth of the war on drugs and our nation’s punitive turn toward mass incarceration. Following the passage of the federal Controlled Substances Act in the mid-1980s, state legislatures began to pass their own state analogs, and both laws and prosecutions have grown exponentially since 2001. Between 2012 and 2018 alone, the recorded number of DIH prosecutions jumped from 109 to 696. As of 2019, 25 states have implemented legislation empowering prosecutors and judges to impose and adjudicate these and related charges.

Pennsylvania, in particular, has racked up a total of 781 DIH charges between 1974 and 2018. DIH charges are also pursued disproportionately against Black and brown people, who are sentenced, on average, to terms nearly two times as long as those of white people.

For all the hype and hysteria, treating accidental overdose deaths as homicides is not effective in reducing rates of drug overdose deaths. For one, because the zealous prosecution of these offenses has continued unabated; and drug overdose fatalities continue to increase nationwide, including in states known for aggressively prosecuting them. Yet many elected officials continue to push for the use of DIH charges. This incongruity rests on a number of myths pushed by carceral actors. But they’re just that: myths. Here’s why you shouldn’t believe them:

First, criminalizing people who sell and use drugs “amplifies the risks of fatal overdoses and diseases, increases stigma and marginalization, and drives people away from needed addiction treatment and other medical and harm reduction services,” reports the Drug Policy Alliance. In other words, that rather than diminishing the harms of drug misuse, criminalization makes things worse.

Second, research suggests that fear of criminal prosecution stands as a significant deterrent to seeking emergency medical help after witnessing overdoses. High-profile coverage of DIH cases and the resulting legal aftermath — including those involving Michael K. Williams, rapper Mac Miller, and actor Philip Seymour-Hoffman — only fuel this cycle of fear. Public health initiatives, such as Good Samaritan Laws, aim to encourage calling for medical help, preventing fatal overdoses. But these policies are rendered useless by enforcement of DIH laws, and remain underutilized tools in ensuring a timely response to an overdose.

Third, misplaced attempts to use carceral solutions to a public health problem means that proven overdose prevention strategies — like medications for opioid use disorder, overdose prevention education, and naloxone — are underutilized and underfunded. The very idea of pinpointing the point of sale as the “cause” of an overdose death is an exercise in distraction — and means that we are not dedicating attention and resources to the underlying causes of what is a public health crisis. Add to that the reality that the vast majority of these cases are actually brought against street-level drug dealers and the loved ones or co-users of the those who died. Indeed, DIH laws are often wielded against those reeling from the aftermath of a fatal overdose.

The Drug Policy Alliance has reported that the cost of incarcerating three individuals for drug-induced homicide equates to “approximately 100,000 doses of naloxone — 100,000 potential saved lives for the price of three ruined ones”. In Mr. Williams’ case, the government expended resources to fly officers to Puerto Rico and to pay for countless hours spent analyzing license plates, inspecting surveillance videos, and scouring Mr. Williams’ cell phone to determine his whereabouts prior to his overdose. In announcing Mr. Cartagena’s prosecution, the lead prosecutor name-checked no fewer than six different law enforcement agencies and task forces that worked on the case, which only underscores how burdensome and wasteful these cases can be.

The unrelenting focus on imprisonment for so-called drug offenders means that funds are siphoned away from programs and policies that could save lives.

When we consider those who are using, incarceration does not decrease substance use rates, either. Our country’s misguided approach to drug use is also reflected in carceral policies that target users and street-level dealers, who are often users themselves. One-fifth of the nearly 2.3 million people incarcerated in the U.S. are serving time for drug-related offenses. Amongst this cohort, research has found that carceral approaches are simply not effective in decreasing rates of substance use — or in improving associated mortality rates.

Rather, incarceration is associated with increased risk for fatal overdose. And this goes beyond people with DIH convictions. Everyone now serving a term of incarceration faces diminished life prospects: Those recently released from carceral settings are at a 129% greater risk of death from overdose than the general population. Incarceration worsens, rather than improves, drug-related harms.

The lingering emphasis on punishment rather than harm reduction for substance use is dangerous and disproportionately distributed, contributing to existing disparities along racial and socio-economic lines in broader applications of law enforcement and social support. It is critical that we curb the use of drug-induced homicide charges to avoid the perpetuation of already-appalling racial disparities resulting from drug law enforcement.

Public Health Approaches to the Overdose Crisis

Expanding access to the continuum of evidence-based prevention and treatment strategies, rather than fixating on punitive measures such as DIH laws, will reduce overdose mortality and related harms. More resources must be directed towards harm reduction services, such as overdose prevention, syringe access programs, and safe consumption sites.

Harm reduction is based on upholding the dignity and humanity of people who use drugs and bringing them into a community of care. This minimizes negative consequences and promotes optimal health outcomes. Harm reduction initiatives also work to combat the harms of racialized drug policies that disproportionately prioritize enforcement and incarceration over public health. The leading cause of death in the United States for those under 50 is accidental drug overdose. Most of these deaths are preventable, but effective strategies must be implemented in order to make a difference.

Many innovative solutions to prevent overdose exist and are firmly backed by research.

Some current harm reduction suggestions include:

- Equip members of your community with naloxone (an FDA-approved drug that reverses overdose) and train them in how to use naloxone in emergency situations.

- Advocate for broad protections under state Good Samaritan Laws.

- Create and maintain supervised consumption site programs to provide a safe place to use drugs with rapid overdose response and social support capabilities.

- Promote sterile syringe access programs, which lessen the risks of HIV and hepatitis C by providing clean syringes and disposing of used ones.

- Implement substance testing (also known as adulterant screening) which identifies the substance and any potentially dangerous contaminants.

- Provide access to and funding for medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) for people who use drugs who choose to start treatment.

David Simon, the creator of The Wire, tweeted after Mr. Williams’ death that the late actor would be appalled that incarceration, through the prosecution of his own and other overdose deaths, was used in his name. DIH laws are a calling card of the protracted, and failed, war on drugs. Like many other hyper-punitive tactics, they achieve little other than the perpetuation of drug and other related harms beyond just people who use, to others in their circles. The overdose crisis is a public health emergency — one that demands effective responses. By doubling down on war on drugs approaches, this prosecution and so many others like it desecrate the memory of Michael K. Williams and do not save lives.

Image: Janet Hu/Unsplash