In the social sciences, dependency theory has often been used to explain the exploitative dynamic between richer and poorer countries. Dependency theory proposes that poor countries are not inevitably reliant on rich ones. Rather, this dependence is orchestrated by rich countries through extraction of natural resources and exploitation of the labor power of working classes. In turn, rich countries are dependent on their exploitation of poor countries to maintain superior status.

In this essay, we ask whether dependency theory can also help make sense of our police-centered world. After all, police operate in much the same way as rich countries, and policing is as dependent on political-economic inequality as it is exploitative of marginalized populations.

In what follows, we offer some background on dependency theory before diving into three illustrative cases of dependency, examining them through an abolitionist lens. Finally, drawing on this discussion, we describe how dependency theory can make sense of contemporary reliance on police and point the way toward how we can loosen this stranglehold.

Dependency theory was first embraced by radical scholars in the mid-twentieth century as a tool of decolonization, useful in helping to analyze how colonial powers had structured global resource and labor exploitation to their benefit. We extend the concept of dependency in three ways that differ from its previous uses. First, we extend the concept beyond economics into policing. Second, we engage with the concept on multiple scales, including municipal and national, and not just the global perspective. Third, we argue that policing functions much the same way as the global exploitation identified by dependency theory; it relies on the exploitation of marginalized populations.

Dependency theory describes global political economic systems as exploitative of countries in the Global South for the benefit of countries in the Global North. For this global system of exploitation to function, it needs to be enforced. Police, who possess unparalleled authority and capacity to use violence, constitute the enforcement mechanism of these exploitative relations. At the global scale, there are international police, such as Interpol. There are also “peacekeeping” forces as well as national armies of Global North countries scattered throughout the Global South. Most prominently, the United States Army has bases on six of the seven continents (and in outer space as well).

These police make exploitation possible, and the relationship is reciprocal: police thrive when resources are extracted from marginalized populations. Moving from the global scale to the local, abolitionist scholar Ruth Wilson Gilmore coined the term organized abandonment to describe how the intentional disinvestment from communities leads to the gradual disappearance of resources and labor value/power within them. There is an inverse relationship between public resources and police. As resources are extracted, policing in its various forms increases, both to sustain the extraction and to manage the social insecurities that extraction causes. What is more, police have become powerful political actors in their own right, experts at making arguments to increase their budgets, especially in times of austerity.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Inquest, finalist for the 2025 National Magazine Award for General Excellence, brings you insights from the people working to create a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest in your inbox every Saturday.

Newsletter

Below we discuss three cases that illustrate—across local, national, and global scales—how contemporary dependence on policing serves important social, political, and economic functions, while helping to concretize regimes of exploitation. In the first case, The Municipal, we provide an illustration of the manufactured dependence of marginalized people on police. In the second case, The National, we discuss how policing represses political dissent, as well as the dependence of propertied stakeholders on this function. In the third case, The International, we present an instance of devolution of reliance on policing after exploitation and extraction. We selected these examples for their range, breadth, and unfamiliarity: they illustrate how deep dependency on the police runs, and the different forms it takes.

Case 1: The Municipal

In legal scholar Monica Bell’s 2016 study of low-income Black mothers residing in public housing in Washington, D.C., forty-seven of the fifty women Bell interviewed criticized the police. To be sure, praise of police was common as well (forty-two women). But the criticisms leveled against police were deep, including descriptions of police as “crooked” and multiple references to specific incidents of police theft, violence, and human and constitutional rights violations, along with the complaint that police couldn’t handle gang problems and violent street crime. Despite these criticisms, thirty-three of these Black women reported calling the police at least once; many had called multiple times.

Bell’s interviews reveal explanations for this apparent contradiction. Police were often the only means available for these mothers to address social problems. This is an example of organized abandonment. In one case, a mother was struggling to compel her son to attend school. His frequent truancy threatened her parental custody rights, potentially triggering child welfare investigations and a criminal conviction. Despite her deep distrust of the police, she called them on her son. Involving the police repositioned the woman as an agent of the carceral state, but she viewed this step to be necessary because it allowed the woman to demonstrate to a different arm of the policing system, the family policing system (child protective services), that she deserved to continue to be her child’s mother. While this strategy was adaptive, it also illustrates her profound dependency on police; she had to call one branch of the police to defuse the threat posed by another branch.

In another example, a woman in a dispute with her neighbor called the police as a preventative measure. The rule in her public housing complex was that a single violation was enough to trigger eviction. Thus, if her neighbor had called the police on her first rather than the other way around, she would have been kicked out of her home.

As these examples show, Black mothers in public housing in Washington, D.C., have been made dependent on police. Absent other social resources, these Black mothers are reliant on police to mitigate noise complaints, domestic violence, child behavior problems, and disputes with neighbors—despite the social power hierarchy that disadvantages and harms them. What is more, the housing authority itself is encased in police and surveillance; the authority depends on police to maintain social control.

Case 2: The National

A key function served by police is the repression of dissent. The powers that be depend on policing to quash political resistance to their extractive projects. This often takes the specific form of having police defend property against damage by protesters. For example, in 2016 the North Dakota Access Pipeline was slated for construction across multiple states on land that is, under the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty, unceded Lakota territory. This pipeline project threatened the water supply of the Standing Rock Indian Reservation and led to massive resistance, as members of more than 300 tribal nations and their allies gathered. A network of police—a mix of public, private, local, state, and national agencies—formed to quash this resistance; the network was overseen by TigerSwan, a military contractor. The violence unleashed by this policing network eventually decimated the protests, and the oil pipeline was built, although resistance to the project continues. Since then, at least eighteen states have passed laws criminalizing anti-pipeline protests, facilitating further policing of future protests.

This is an example of the critical role played by police in resource extraction from marginalized populations. When corporations seek to extract resources from land occupied by marginalized groups, police are brought in to overcome resistance, ensuring the corporation’s access to these resources.

Case 3: The International

The Pacific nation of Nauru has been decimated by the phosphorus industry since the turn of the twentieth century. This resource extraction has ravaged the previously lush island of its soil minerals. Without these minerals, Nauru residents cannot grow their own food and must instead rely on ultra-processed foods imported from the West, creating economic dependence and leading to the rise of diabetes and other inflammatory diseases.

The original decision to extract phosphates from the soil was not made by Indigenous Nauruans but by colonists: first the Germans and, after World War I, the Australians. The colonists priced the extracted phosphates low as a means of subsidizing their own farmers, a clear case of wealth transfer. The colonial powers carried out this resource extraction with military might.

While Nauru achieved formal independence in 1966, the island’s economy remained tied to the fate of the West, as it now relied on exporting phosphates. After the primary supply of phosphates was exhausted and island leadership squandered money its trade of phosphates had yielded, Nauru’s economy went on life support. Desperate for income, Nauruan policymakers in the early twenty-first century turned to a form of racialized policing: immigration policing for Australia in return for per capita payments. As with women in public housing in Washington, D.C., we see dependence on policing even among the “losers” in the game of global resource extraction.

Instead of being able to migrate to fertile lands, there is an international system of passports and visas, facilitated by Australia and Indonesia, that impedes most Nauruans from global mobility. The colonial countries that profited from exploitative phosphate mining now depend on a form of global political-economic policing to profit from Nauru’s dependence on imported ultra-processed foods. This case shows that police dependence is not relegated to the Global North but also lies everywhere capitalist exploitation thrives.

Policing in its violent historical and modern implementation is not a bug of capitalist societies but a feature. Dependency theory serves as an excellent framework for analyzing our society’s political and economic reliance on policing. The three cases offer examples of this reliance. The first case, focused on Washington, D.C.,shows how economically marginalized populations are made dependent on policing by organized abandonment, economic divestment, and political design. The second case, focused on Standing Rock, illustrates how police function to repress political and economic dissent, and how corporations and private interests are reliant on this role of police, enshrining it in law. The third case, focused on Nauru, demonstrates how dependency theory explains policing not only in the Global North, but also within other nations and between nations too.

Dependency theory can help make sense of our police-centered world and its reliance on police. Attempts to abolish police must reckon with this deep-seated police dependence. To align ourselves against police requires us to align ourselves against the relations of wealth extraction that police make possible.

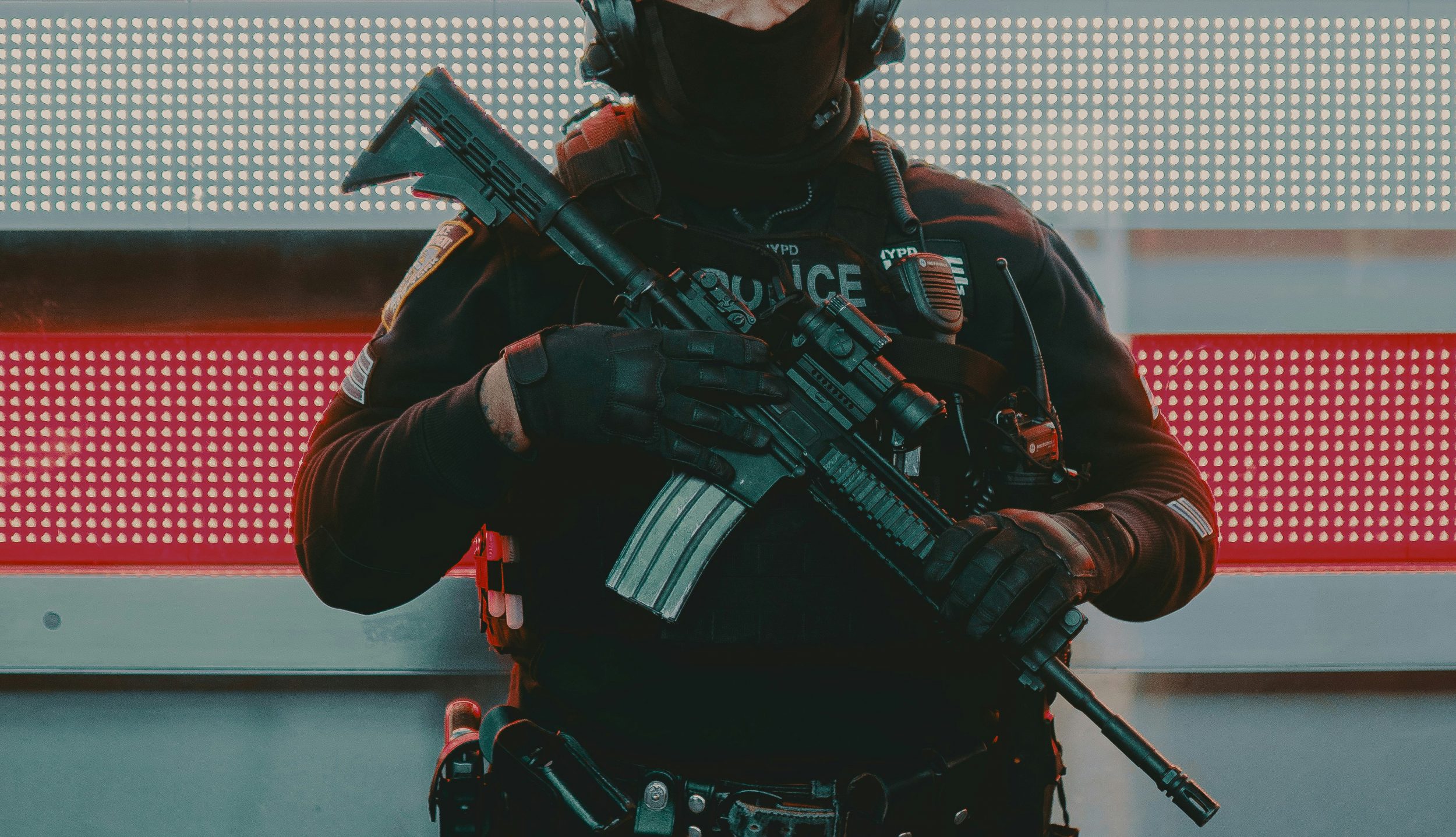

Image: Alec Favale / Unsplash