I first heard about “Eric” on the evening news when I saw the headline “Teen Arrested for Bringing Explosive Device to D.C. School.” The story immediately caught my attention. It sounded serious, and as a defense attorney practicing in Washington, D.C.’s juvenile court, I knew I would likely see Eric in court the next day. Indeed, as fate would have it, just as I walked into the courthouse, a teenage girl approached me to ask if I could represent her brother — Eric. Coincidentally, I had met Eric’s sister a few months earlier in a drama workshop at a local high school. And when I checked in with the court staff the next morning, I learned that I had already been appointed to Eric’s case.

Within minutes of talking to Eric in the juvenile lockup, I realized that what sounded so shocking on the news wasn’t so serious after all. Eric was a typical 13-year-old boy who was watching a movie and saw someone with a Molotov cocktail. Eric thought it was “cool” and wanted to see if he could make something that “looked” like that. He grabbed an empty bottle from under the kitchen sink and started filling it with household products — bleach, Pine-Sol, stainless steel cleaner — whatever he could find. He didn’t research it. He didn’t look up “Molotov cocktail” on the internet, and he didn’t know if any of the products he grabbed were flammable. He was just being creative. He taped up the entire bottle with black tape and put a long piece of toilet paper underneath the cap so it hung out of the bottle like the wick of a cocktail. After admiring his design, Eric put the bottle in his book bag so it wouldn’t spill on his mother’s white carpet and moved on to his next source of entertainment for the day. This all happened on a Saturday night, and like most 13-year-olds, he had completely forgotten about it by Monday morning when his mother drove him to school. As he did every school day, Eric walked through a metal detector and put his bag on an electronic conveyor belt. A police officer assigned to the school as a so-called school-resource officer saw the bottle and stopped Eric to ask about it. Eric responded without thinking, “Oh, that’s nothing. You can throw it away.” He walked on to class. Little did he know this was the beginning of a very long and painful ordeal for him and his family in juvenile court.

Eric was pulled out of class, questioned by the police, and arrested. No one believed him when he told them he forgot the bottle was there and was not planning to blow up the school. Eric spent the night in the local juvenile detention center and was brought to D.C. Superior Court the next day. The prosecutor charged him with possession of a Molotov cocktail, attempted arson, and carrying a dangerous weapon. When I heard the prosecutor read out the charges, I kept expecting there to be more to the story — maybe a letter or some cryptic online message by Eric threatening to hurt a teacher. Maybe Eric was sad, isolated, and bullied by his classmates. Maybe Eric had a history of depression and dressed in all black. None of that turned out to be true. There was nothing more to the story.

Quite to the contrary, Eric was a happy and creative Black boy living in Southeast D.C. with his mother and little brother. Although his father was in prison at the time, Eric was raised in a large, close-knit family, including two older sisters in college and another in the U.S. Air Force. His mother worked in a hospital and catered food a bit on the side while studying for her nursing degree. His father was a college graduate who had worked for many years as an emergency medical technician before his incarceration. I visited Eric’s home many times and met many of his family members over the next several months. I saw nothing other than a well-adjusted boy who loved to show me his kittens and play with his brother. He was active in youth theater, participated in the city’s local youth orchestra, and tutored second and third-grade students in reading four days a week. He also enjoyed youth activities at church. His teachers described him as calm and respectful, and he had never been in trouble at school or with the police.

The only thing that could really explain the school’s extreme reaction to Eric’s duct-taped bottle was our country’s outsized fear of school shootings. And for a while, I accepted that as the reason. I let myself believe that our schools were just being extra careful in the era of mass violence. But then something happened that forever changed my view of this case. Several months after I met Eric, I shared his story at a conference in New Haven, Connecticut. When I finished, a white woman walked over and said, “My son did exactly what you described. He tried to make a Molotov cocktail and took it to school.” When I asked what happened to her son, she said, “They rearranged his class schedule so he could take a chemistry course.”

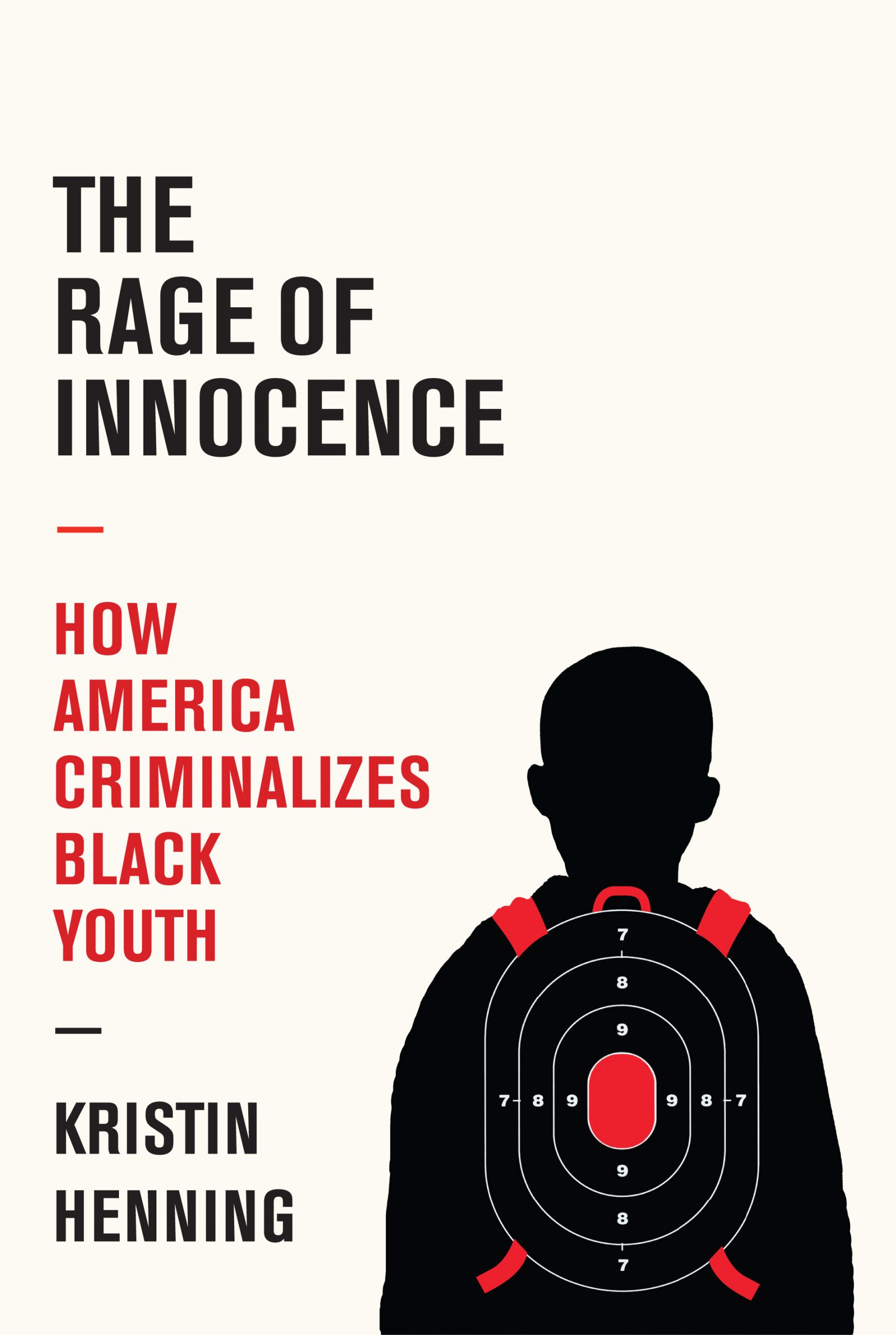

No, we are not just afraid of school shootings. And we are not just afraid of children with guns. We are afraid of Black children. There was nothing Eric could have done or said that day to convince the police or anyone else that he was not a threat to the school.

We live in a society that is uniquely afraid of Black children. Americans become anxious — if not outright terrified — at the sight of a Black child ringing the doorbell, riding in a car with white women, or walking too close in a convenience store. Americans think of Black children as predatory, sexually deviant, and immoral. For many, that fear is subconscious, arising out of the historical and contemporary narratives that have been manufactured by politicians, business leaders, and others who have a stake in maintaining the social, economic, and political status quo. There is something particularly efficient about treating Black children like criminals in adolescence. Black youth are dehumanized, exploited, and even killed to establish the boundaries of whiteness before they reach adulthood and assert their rights and independence.

The Invention of (White) Adolescence

Most of us take adolescence for granted as a distinct stage of life bridging childhood and adulthood. But it is actually a relatively new concept. The modern idea of adolescence did not appear until the late 19th century and didn’t gain widespread traction until the 1950s or 1960s. Before the Industrial Revolution (1760–1840), we thought of development in only two stages, with childhood including anyone under the age of 18, or sometimes 21, and adulthood including everyone else. As industrialization shifted the nation’s economy from farming to manufacturing, the role of children also changed. In 1860, 72 percent of those employed in the United States worked in agriculture. By 1930, that number had decreased to 21 percent. Children raised in agrarian cultures were expected to work and contribute to the upkeep of the family just like adults.

After the Industrial Revolution, the number of youth working in the field decreased, and the number of youth enrolled in high school and college increased dramatically. Shifts in the workforce created higher-paying jobs that required skilled labor and advanced education. In response, many parents, especially those in the middle class, encouraged their children to stay in school to develop the skills they needed to succeed. In 1900, 43 percent of 14- and 15-year-old boys and 18 percent of 14- and 15-year-old girls were employed in the United States. By 1930, only 12 percent of boys and 5 percent of girls were working at that age. At the same time, the number of students enrolled in public high schools increased from 519,000 in 1900 to 3.9 million in 1928. In 1852, Massachusetts became the first state to pass a law requiring children to attend school. By 1900, most northern and western states had passed similar “compulsory education laws.” Enrollment in college and professional schools also increased after the Industrial Revolution. In the 1890s, the number of students enrolled in colleges increased by 38.4 percent, and the number of medical, law, dentistry, pharmacy, and other professional schools doubled between 1876 and 1900.

Adolescence was essentially “invented” — by white, middle–class parents — to give their children an advantage in the changing western world. Adolescence brought with it the privilege of extended education, prolonged self-discovery, and new opportunities for fun and leisure. In the transition to adulthood, society expected — or at least hoped — youth would not only develop new skills but also test boundaries, wrestle with moral dilemmas, and find their special talents. Parents and teachers taught children about the important responsibilities of family, work, and community but gave them time to think independently and shape their own identities.

This newfound adolescence wasn’t always greeted with joy. Adolescence originated at a time of considerable upheaval in the United States, and some worried that this new period of freedom would weaken the family and wreak havoc on society unless young people were controlled. As workers moved from the country to the city in search of industrial jobs, families changed and society seemed less orderly. Many believed that young people were the cause of that disorder and should be regulated “at every turn.”

American psychologist G. Stanley Hall emerged as the “father of adolescence” in 1904 when he wrote about the physical and biological changes that begin with the “growth spurt” and conclude with the end of physical development, usually in a person’s 20s. Although Hall focused on the physical changes that occurred during adolescence, he was also concerned about the character and personality traits that accompanied those changes. Hall described adolescence as a time of “storm and stress” and believed that adolescents should be protected and excluded from adult activities.

Responding to Hall’s work, cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead argued that the characteristics of adolescence were caused by the cultural pressures of western society, not biology. Although Hall and Mead disagreed on the cause, both expressed an increasingly negative view of adolescence and advocated for new social programs that would monitor and control young people.Heeding the call for increased supervision and more opportunities to teach youth moral values, states not only passed mandatory school attendance laws but also expanded laws to reduce child labor and created a special juvenile legal system to deal with delinquent youth. These policies allowed states to impose middle-class values on youth and further separated adolescents from children and adults.

Although most psychologists no longer talk about adolescence as a time of “storm and stress,” they do remind us that it is a season of impulsivity and recklessness. During adolescence, the brain changes in ways that affect how we seek out and enjoy pleasure, how we control ourselves, and how we interact with other people. Changes in the brain that accompany puberty make us more easily aroused by our emotions and more likely to become angry or upset at a time when we don’t have the capacity to fully regulate our thoughts, emotions, and actions. These changes also increase our willingness to take risks and chase excitement.

Researchers have been collecting data about teenagers’ behavior for years. Forty years of adolescent self-report studies from the University of Michigan and the Centers for Disease Control confirm that youth of all races and ethnicities admit involvement in risky, irresponsible, and even dangerous behaviors. In 2018, 58.5 percent of high school teenagers surveyed in the United States reported that they had tried alcohol by the 12th grade, 42.9 percent had been drunk, and 49 percent had tried marijuana. More than 39 percent reported having had sex, and within that group 13.8 percent reported that they had used no protection to prevent pregnancy. Nothing in this data collection suggests that Black youth are inherently more reckless, impulsive, or dangerous than white youth. In fact, notwithstanding some differences in the type of drug, type of weapon, or age at the onset of such behaviors, white youth report risky behaviors at rates similar to — and sometimes higher than — Black and Hispanic youth.

All of these behaviors arise out of the same impulsive, short–sighted features of adolescence that are common among youth of all races. Yet we don’t treat youth of all races the same. Poor Black youth who experiment with drugs and alcohol in public spaces like a park or a street corner are more visible — and appear more dangerous — than wealthier white youth who use drugs in the privacy of their own homes and clubhouses. Black youth who have greater access to more stereotypically frightening drugs like crack are demonized as violent criminals, while white youth who can afford more expensive drugs like powder cocaine are excused as impulsive and experimenting teens. Teachers and counselors who are inundated with negative images and faulty narratives about Black youth in poor, urban schools are less likely to tolerate and forgive adolescent misconduct than teachers who work with white youth in rural or wealthy communities. And police officers who are vulnerable to racial bias and stereotypes in fast-paced and stressful encounters with youth make snap judgments and racialized assumptions about what they see and how they will respond.

At every stage of the juvenile legal system, Black youth are treated more harshly than white youth. Despite years of evidence that white youth use drugs at the same rates as Black youth or higher, 19 percent of all drug cases referred to U.S. juvenile courts in 2018 involved Black youth. This data is notable when we consider that only 15 percent of youth in the juvenile-court age range that year were Black. Black youth also accounted for 35 percent of all juvenile arrests for any crime in 2018 and 40 percent of all cases in which the youth was sent to a detention facility to await trial or sentencing. Black youth accounted for 39 percent of all cases formally processed in a juvenile court, 37 percent of all cases in which the youth was found guilty, and more than 51 percent of youth whom a judge transferred from juvenile court to be tried as an adult.After they were found guilty, Black youth accounted for more than 41 percent of all cases in which the youth was placed in secure or nonsecure residential settings.

So if the science and the data tell us that white youth act a lot like Black youth, then why don’t we treat Black youth the same? The answer is simple: We don’t see Black children as children.

So if the science and the data tell us that white youth act a lot like Black youth, then why don’t we treat Black youth the same? The answer is simple: We don’t see Black children as children.

One area where Black children are robbed of their childhood in ways white children aren’t is in our collective failure to accept that they, too, can play with toy guns. Toy guns are a staple of adolescent play. A quick Google search turns up several Top 10 lists for the “best toy guns of the year.” Water guns, paint guns, guns in virtual video games, BB guns, cap guns, dart guns, and Nerf guns are standard merchandise in Walmart, Target, Amazon, and the local dollar store. Boys — and girls — play with guns at home, in the park, and at school. Entire parks are devoted to paintball guns. Cops and robbers, cowboys and Indians, and war games are common themes at the movies and on the television screen.

Playing with guns, especially among boys, has been a common feature of American culture for centuries. It wasn’t until the 1980s and 1990s that parents and teachers began to worry about the dangers of toy guns. Despite sporadic attempts to ban them after high-profile school shootings, toy guns remain popular in the 21st century. Surveys show that about 60 to 80 percent of boys and about 30 percent of girls play with aggressive, toy-like guns at home. Even when parents refuse to buy them, childre chase after each other yelling “pow pow” and pointing their thumb and forefinger in the shape of a gun. Toy guns are inescapable. Cartoons like Looney Tunes, Batman, The Simpsons, Family Guy, The Boondocks, and Pokémon have all aired episodes with guns. The cartoon images are so plentiful that in 2014, Democrats attempted to ban gun manufacturers from using cartoon characters to market guns. The bill never passed.

Contrary to common fears, research offers no scientific evidence that playing with toy guns in childhood leads to violence later in life. In fact, some have argued that roughhousing, verbal dueling, playing with toy weapons, and war games might be good for children who learn to negotiate power and achieve victory in the safety of fantasy and play. Of course, the toy industry has resisted any claim that toy guns themselves encourage aggressive behavior and prefers to highlight the benefits of friendly competition, exercise, and an active mind.

A Tragic Case Study

Given the saturation of toy guns in our society, we shouldn’t be surprised or even worried about a 12-year-old boy playing with a toy gun at a local park on a lazy Saturday afternoon. But that’s exactly what happened in Cleveland on November 22, 2014. Someone was very worried.

He looked big for his age.

tim mcginty, Cleveland county prosecutor

Shortly before 3:30 p.m., a park visitor called 911 to report that someone, “probably a juvenile,” was pointing a “pistol” at random people at the Cudell Recreation Center in Cleveland. Twice, the caller told dispatch the gun was “probably fake.” When a police car sped onto the Cudell park lawn, 12-year-old Tamir Rice was sitting on a picnic table in a gazebo. One of the officers in the car, Timothy Loehmann, jumped out and shot Tamir two times in the chest. Loehmann later said he saw a Black male pick up a black gun and put it in his waistband. The car carrying Loehmann and his partner had not come to a complete stop before Loehmann fired his weapon. Within two seconds of the officers’ arrival, Tamir was shot down.

It turns out that Tamir had been holding an imitation pistol — or an “airsoft” replica gun, popular among children and sold at places like Walmart and Dick’s Sporting Goods. Surveillance video shows that Tamir had been walking around the park earlier, occasionally extending his right arm, and talking on the phone. Tamir’s mother said that a friend gave him the toy shortly before he went to the park.15

So many things went wrong that afternoon. At the outset, the police dispatcher never told officers that the 911 caller said the gun was probably fake and the person holding it was probably a child. Although the officers approached the gazebo from the safety of their car, they did not take any time to assess the situation before jumping out to fire. The officers drove up at a high rate of speed, stopped less than ten feet from Tamir, and did not take cover inside or behind the car long enough to ask questions and allow Tamir to respond. Contradicting the officers’ claims that they had repeatedly yelled “Show me your hands!” through the open car window, several witnesses reported that they never heard any verbal warnings before the gunfire.

Even with a warning, two seconds is an incredibly short time for anyone — especially a 12-year-old — to process an officer’s commands and comply. And Loehmann, who had been deemed emotionally unstable and unfit for police duty prior to joining the Cleveland force, was never prosecuted for killing Tamir. Two experts on police use of force concluded that the shooting was reasonable under the circumstances.The county prosecutor, Tim McGinty, blamed the shooting on human error, mistakes, and miscommunication by all involved.

McGinty’s analysis ignored a critical variable — race. Tamir’s death was much more than the sum total of administrative and procedural errors. His death draws us to the center of what it means to be Black and adolescent. It wouldn’t have mattered if the officers had been told that the person in the park was probably a child or the gun was probably fake. When officers arrived on the scene, they saw a Black male with a dark object. That alone made him “dangerous.” Tamir’s race negated any possibility that he was a child — playing in a park, with a toy.

If you were ever outraged about Tamir’s loss of life and innocence then, as I was and still am, please know that his case was not an exception. In ways large and small, what the state did to Tamir is what we routinely do to Black children: Deny them their childhood. His life mattered. The lives of Black youth in America matter. And anyone who wants to change the way Americans view and engage with Black children, can start today by seeing them for what they are.

For Black children are children, too.

Excerpted from The Rage of Innocence: How America Criminalizes Black Youth by Kristin Henning, to be published by Pantheon Books on September 28, 2021. Copyright © 2021 by Kristin Henning.

Image: Unsplash