Signaling a break with his predecessor, Joe Biden promised to “follow the science,” a line he repeated over and over during his campaign. He also made the dual pledge to reform the criminal legal system and to rely on a public-health approach to combat the nation’s opioid crisis. Driving the point home, he declared, after becoming president, that “no one should go to jail for the use of a drug.”

But his administration’s latest proposal, sadly, is more of the same. Earlier this month, the Biden administration asked Congress to make permanent the classification of certain fentanyl analogues into Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act — a request that, if heeded, would go against scientific evidence, the need to treat opioid abuse as a public-health emergency, and the president’s own stated ideal that no one should be imprisoned over drug use.

By proposing to make classwide scheduling permanent, the administration is supporting an unprecedented — and harmful — shift in drug control policy that may mark the final ouster of public health agencies from drug control decisions. In many respects, classwide control would be the culmination of a steady, 50-year campaign to tilt the balance in drug-control decision making away from science and towards enforcement, criminalization, and incarceration. But Congress doesn’t have to follow along. Lawmakers have a generational opportunity to truly lead with science and truth in this area — the very things Biden promised those voters who elected him president.

Best of all, Congress doesn’t have to do a thing. Simply by not acting, it will allow the current punitive regime to expire.

To understand why we’re here, and why inaction is the best action Congress could take after decades of a failed, enforcement-first approach to drug policy, we need a historical primer on how science and public-health have been all but evicted from drug scheduling.

Since the dawn of modern drug policy, the United States has pretended to hew to a dual approach to illicit drugs, one that emphasizes law enforcement and public health in roughly equal measure. That duality is a farce: Federal funding for enforcement has historically dwarfed public health and other demand-reduction strategies, and 50 years of the same approach to drug policy have shown that the whole enterprise has been a spectacular failure.

Federal funding for enforcement has historically dwarfed public health and other demand-reduction strategies, and 50 years of the same approach to drug policy have shown that the whole enterprise has been a spectacular failure.

To this day, headlines still abound with reported large-scale drug seizures and ever-present arrests, but none of this has reduced the demand that drives the supply. The overdose crisis, which has run parallel to the war on drugs for decades, is “the clearest indictment so far of the failure of prohibition to curb drug use,” as experts in drug policy recently put it. Meanwhile, tens of millions of Americans continue to struggle with substance-use disorder and its consequences. And enforcement policies have come at an unfathomable cost, sending far too many young men of color to crowd our prisons, leaving broken families and communities in their wake.

This is by design. Law enforcement has successfully lobbied to expand its authority over drug control since the 1970 enactment of the Controlled Substances Act — which established the system of categorizing drugs based on their “potential for abuse” and whether they have an accepted medical use by placing them on one of five schedules. Enforcement and criminalization flow through scheduling; placement of a drug on the schedules gives the federal government the authority to prosecute and often sets the severity of penalties for illicit use, manufacture, or distribution. Convictions involving Schedule I substances often carry the most severe penalties. That’s the “control” in drug control.

When the CSA was first enacted, law enforcement agencies clashed with the medical and scientific community over whether the attorney general or the secretary of the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare (the precursor to the Department of Health and Human Services) would be in charge of drug scheduling decisions. Doctors and scientists warned that drug use should be treated as a public health issue, and that handing law enforcement the responsibility for drug control would permanently skew drug control towards criminalization. Science and medicine lost that fight, and Congress put the attorney general in charge of drug control. But even after that, law enforcement agencies continued to push for more. Dissatisfied with so-called “gaps in the law” and “loopholes” that they regarded as procedural roadblocks to prosecuting emerging drugs, those in law enforcement claimed they needed more control in order to swiftly respond to what they deemed to be a drug “threat.”

Doctors and scientists warned that drug use should be treated as a public health issue, and that handing law enforcement the responsibility for drug control would permanently skew drug control towards criminalization. Science and medicine lost that fight.

So they appealed to Congress. And in 1984 and then again in 1986, Congress awarded enforcement agencies two powerful new tools designed to expedite prosecution: emergency scheduling and the Controlled Substances Analogue Act, also known as the Analogue Act. Emergency drug scheduling gave the attorney general authority to swiftly add new substances to the drug schedules without awaiting a scientific and medical assessment by the health secretary of evidence about a substance and its pharmacological effect. And the Analogue Act gave prosecutors the tools to immediately go after such substances — even before they had been controlled or even identified.

Importantly, both tools retained important checks against the Justice Department and the Drug Enforcement Agency’s drug control authority. Under federal law, a temporary scheduling action cannot become permanent if the health secretary disagrees with the attorney general’s recommendation to control a substance. The Analogue Act requires the government to prove to a jury beyond a reasonable doubt, among other things, that a novel substance has a substantially similar chemical structure and a substantially similar effect as a Schedule I or Schedule II substance. Congress created these checks to ensure accuracy and precision in drug control decisions — and to account for the outsized penalties at stake in federal drug prosecutions.

In all, by the late 1980s, the Department of Justice had amassed a powerful toolset to control and prosecute drugs domestically: the power to schedule drugs in consultation with health and science agencies; the power to schedule drugs (albeit temporarily) without health and science agencies; and the power to prosecute drugs with no health or scientific input required.

And yet these powers were still not enough for law enforcement agencies. So-called designer drugs continued to proliferate, and as the Justice Department made greater use of the Analogue Act, prosecutors soon came to view it as unduly burdensome and began to chafe at it. In 2013, the DEA told Congress that “[t]he Analogue Act answered the designer drug problem at [a] particular time in history,” but was no longer a “deterrent effect” to “large scale foreign manufacture” of drugs. Despite these complaints, a department representative told Congress in 2019 that the “government has a very good track record in Analogue Act prosecutions.”

That brings us to today. The latest chapter in this story is the federal government’s request that Congress make permanent its temporary placement of a “class” of fentanyl-related substances onto Schedule I — so-called “classwide scheduling.” The DEA used its administrative authority to create the class control on February 6, 2018, but the scheduling action cannot become permanent without congressional action. Tellingly, in testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee, the DEA has described classwide scheduling as “untested” and acknowledged their authority for the action was “legally uncertain.”

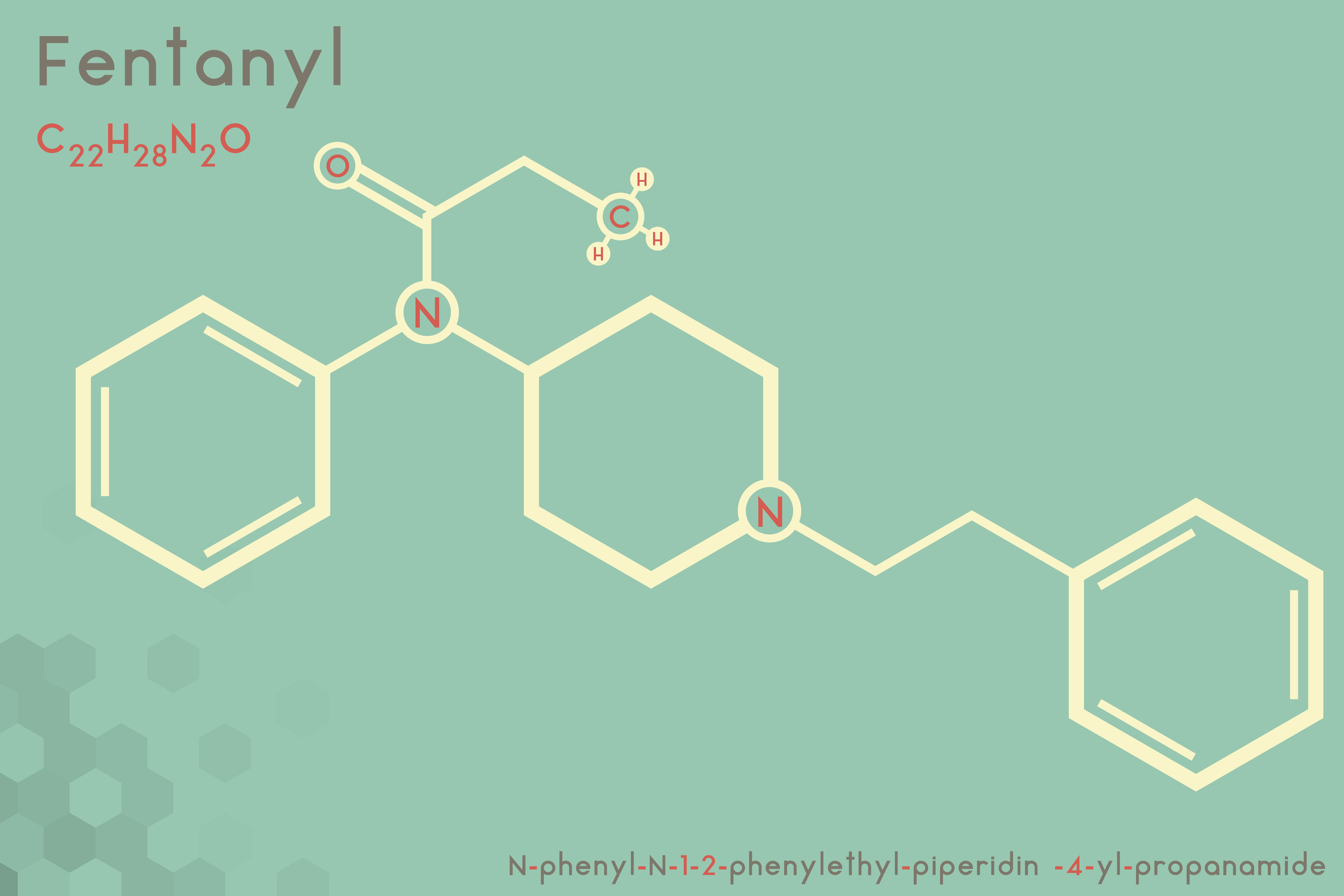

Classwide scheduling preemptively criminalizes drugs based solely on their chemical structure, an approach to categorizing drugs that is not supported by science. That’s because it is impossible to know how a substance will act in the human body by just looking at its chemical structure. For example, Imodium is an over-the-counter anti-diarrhea medicine, with the same core structure as fentanyl, but it does not act on the brain; it acts on the gut. Imodium shows that not all fentanyl analogues are harmful. In fact, fentanyl analogues vary wildly in potency. “Some analogues, like acetyl fentanyl, are less potent than fentanyl; others, like carfentanil, are many times more potent; and still others, like benzylfentanyl, are believed to be essentially biologically inactive,” an official with the Office of National Drug Control Policy told Congress in written testimony in 2019.

Classwide scheduling preemptively criminalizes drugs based solely on their chemical structure, an approach to categorizing drugs that is not supported by science.

The Government Accountability Office, for its part, has found that the DEA’s use of a classwide approach “preemptively includ[es] an unknown number — potentially thousands — of substances that have not yet been identified by [the] DEA and which may not have been developed.” Because of this approach, the class control criminalizes substances that have no place on Schedule I. Scientific research has already identified specific fentanyl-related substances improperly controlled by classwide scheduling that have little to no pharmacological potential for abuse — some even have therapeutic promise. But under classwide control, whether a substance is harmful, helpful, or benign is irrelevant — all are criminalized alike.

DEA and DOJ claim that this authority is a necessary component of an effective enforcement response to fentanyl analogues and rising overdose deaths. Even prior to classwide control, enforcement of fentanyl and its analogues was ramping up. Between 2015 and 2019, prosecutions for federal fentanyl offenses increased precipitously by 3,592 percent, while fentanyl-analogue prosecutions increased by 5,725 percent. In 2018, DOJ launched the Operation Synthetic Opioid Surge, or S.O.S., program, which was designed to prosecute “every readily available case involving fentanyl, fentanyl analogues, and other synthetic opioids, regardless of the drug quantity.”

In the intervening years, public health has not improved. On the contrary, despite this aggressive ramp-up in arrests and nearly three years of temporary classwide scheduling, “deaths from synthetic opioids — the biggest killer — were up by 52% year-on-year in the 12 months to August [2020], the last month for which data are available,” according to a March report in The Economist. The GAO has reported that overall seizures of fentanyl and its analogues “increased substantially” from fiscal year 2018 through fiscal year 2020. Meanwhile, the racially disparate enforcement of drug laws against communities of color persists: The federal Sentencing Commission has reported that, in 2019, 68 percent of those sentenced for fentanyl analogues were people of color, and federal law enforcement agencies have targeted minimally involved individuals and street-level dealers in its fentanyl-analogue enforcement efforts — instead of kingpins, importers, or large-scale manufacturers.

The Justice Department’s “vice-like grip on federal policymakers,” as Professor Shon Hopwood has termed it, hasn’t made us safer. Time and time again, when those policymakers have asked the government to explain why drugs continue to flood into the country, and why overdoses continue to skyrocket, the response rarely varies: The problem is not too much enforcement, they explain, it is not enough enforcement. According to the department, all we need is a way to “make it easier to charge and incarcerate people.” Enforcement needs tools, and when those tools are delivered, drug supply will drop, overdose deaths will decrease, and the public will be safer, the line goes. These promises have never been fulfilled, and they never will be.

In light of this history, the Biden administration’s request to Congress to make classwide scheduling permanent is all the more dismaying because the proposal accepts that classwide scheduling will inevitably misclassify some drugs as Schedule I, and that some people might wrongfully be prosecuted for those substances. But rather than reject this overreach, which could very well destroy lives, the administration embraces what’s essentially a guilty-until-proven-innocent approach — by providing mechanisms to remove substances from Schedule I and to reduce or vacate wrongfully imposed sentences after the fact. The administration’s announcement minimizes the potential harms that will flow from classwide scheduling — and, puzzlingly, touts President Biden’s professed commitment to funding public health responses to drug misuse.

Congress has so far greeted the Justice Department’s earlier request for permanent classwide scheduling with some skepticism, and barring any action by lawmakers by January 28, 2022,* the temporary scheduling of fentanyl-related substances will expire. This is an opportunity for Congress to stop believing the unfulfilled promise that more draconian enforcement measures will end the harmful effects of some drugs, and to reassert the role of science and evidence in federal drug policy.

The Biden administration's pending request to permanently place all fentanyl-related substances on Schedule I may be the last front in the government’s decades-long quest to evict science and health agencies from drug control once and for all.

Indeed, the pending request to permanently place all fentanyl-related substances on Schedule I may be the last front in the government’s decades-long quest to evict science and health agencies from drug control once and for all. It will not be long before the Justice Department returns to ask for the next tool it needs — perhaps to control another class of synthetic drugs, or for the power to control classes of substances with no sign-off from Congress at all. In 2019, DOJ and DEA suggested as much in congressional testimony, observing that there is a need to “address the scheduling system on a more comprehensive basis” so that “savvy illicit drug manufacturers” won’t have a way “to avert current controlled substances scheduling authorities.”

Lawmakers would be wise to ignore this fearmongering. For over 50 years, prosecutors and law enforcement have promised Congress that interdiction, arrest, and prosecution are the panacea to drug misuse and will end overdose deaths. Time and time again, Congress has believed them, expanding their authority and dominance over drug control. Despite this record — if not because of it, and the related refusal to follow the lead of public health experts — almost 92,000 Americans lost their lives to the drug overdose epidemic in 2020. This death toll has been exacerbated and persists due to the acute toxicity of the illicit drug supply. It is time for a new way forward, and the good news is that this time there is law enforcement and other official support for finding a new path, or paths, forward.

Some policing professionals in the United States and notably the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police have recognized the impact of substance use disorder on the communities in which they work. Above all they have found that harmful criminal justice interventions increase stigma, the risk of overdose, and the transmission of blood-borne diseases. Together, these problems have led to health and criminal justice inequities in marginalized communities, especially communities of color. If we are to successfully achieve drug strategies to save drug users’ lives, mitigate the harms of mass incarceration, and uproot systemic inequities that create racial, economic, and health disparities for marginalized communities, we need to design and implement 21st-century drug strategies. Among them is the decriminalization of certain substances and practices and reallocation of resources spent on enforcement toward more effective interventions — such as overdose-prevention sites, which more and more state and local officials are recognizing as valid public-health responses.

As Brandon del Pozo and Leo Beletsky have written, the most effective way to do that is to “place public safety within the framework of population health, with the goal of honoring the sanctity of life.” In other words, an effective strategy will view the law and the government’s exercise of regulatory and enforcement powers as effective only when they pursue and achieve the end of improved public health (and therefore safety), and not when enforcing the law is viewed as an end in itself. Congress can start toward that path by following the science — which in this case simply means doing nothing and letting temporary classwide scheduling of fentanyl analogues expire.

*After publication, Congress extended, and the president signed into law, the deadline for when temporary classwide fentanyl scheduling was set to expire — from October 22, 2021, to January 28, 2022.

Image: iStock