For those seeking to dismantle the machinery of mass incarceration, police and prosecutors have long been a focus. But many have lately come around to the potential of public defense as a site for change. Public defense is uniquely positioned within the criminal legal system: it is a part of the system, but it seeks to protect and support the people targeted by that system. To make matters more complex, the field is not a monolith: different defenders have different motivations and goals, some of which may even be in tension with one another.

I was a public defender for nearly fifteen years. Like other public defenders, I represented people during some of the worst moments of their lives. I spent countless days in courtrooms, arguing to judges and juries. I spent endless evenings and weekends in jail visiting rooms, discussing cases with my clients. I spent hours upon hours at family homes and the scenes of incidents. I researched drug treatment programs and looked for shelter beds. I spent late nights reading records from schools, hospitals, and all of the state agencies that loom large in the lives of people our country criminalizes. I tried to help people return home to their families sooner than they otherwise might have, and I hope I mitigated at least some of the harm that people experienced.

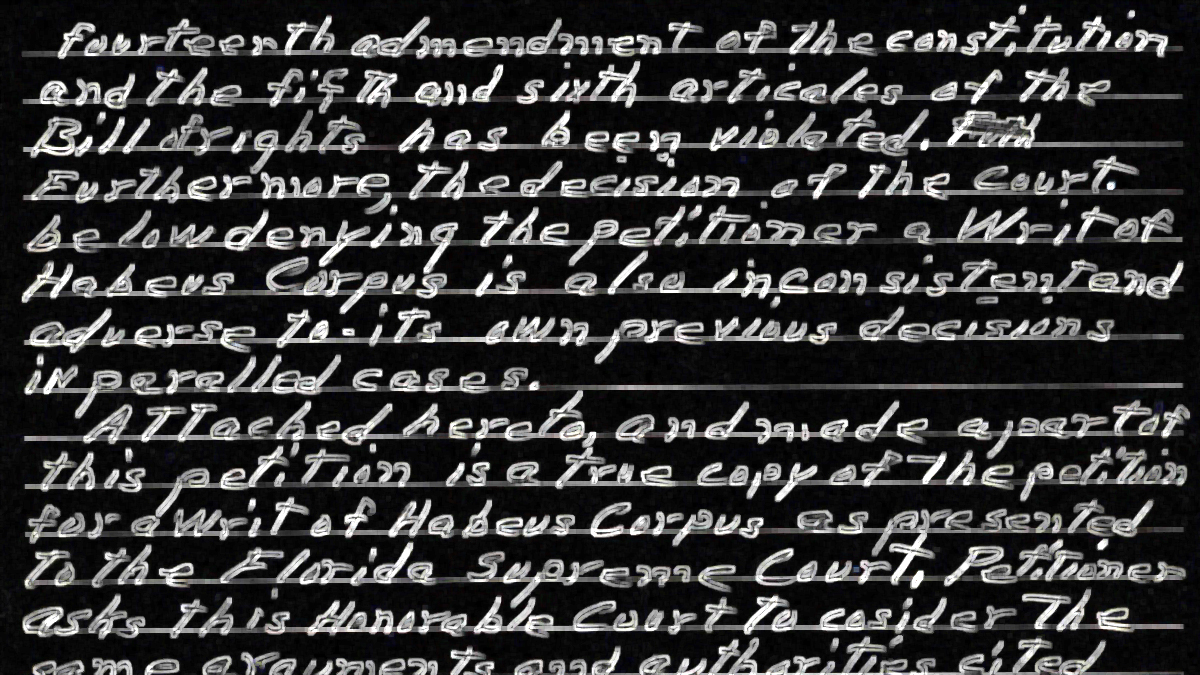

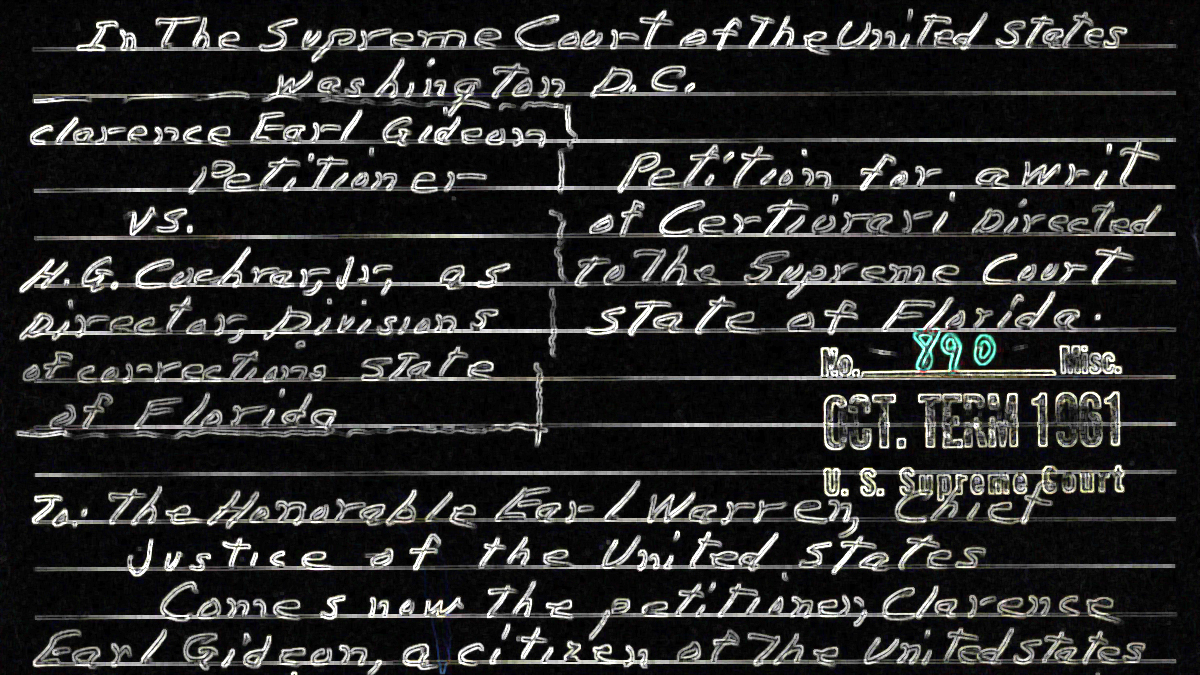

For public defenders in our country, the Supreme Court’s 1963 opinion in Gideon v. Wainwright is a polestar. It’s the opinion that constitutionalized the right to counsel for poor people facing criminal charges—and, in the national imagination, it’s lauded as the righteous origin of modern public defense. Accordingly, many around the country are marking this month’s sixtieth anniversary of Gideon as a great moment in the history of our democracy.

This essay is from the series

Beyond Gideon

A collection of essays examining how—or whether—public defenders can meaningfully contribute to the end of mass incarceration.

But what did Gideon truly stand for? What has it given us? What progress has it facilitated? The Gideon court wrote, “In our adversary system of criminal justice, any person haled into court, who is too poor to hire a lawyer, cannot be assured a fair trial unless counsel is provided for him.” The benchmark, then, according to Gideon, is a fair trial.

There are scores of defenders for whom public defense is much more than that. For whom justice does not end at, or even necessarily relate to, a fair trial. For whom the reality of structural and individual racism necessarily calls into question any supposed fairness in our criminal legal system.

Public defense can be leveraged to do so much. It can be channeled toward the work of challenging our system of mass incarceration. But how?

In recent years, there has been a surge in the number of public defenders eager to make change. They are pushing for an end to the harms enacted by the carceral state while doing the essential daily work of disentangling their clients from its tentacles.

Our system of mass incarceration is a vast network of policing, prosecution, incarceration, surveillance, debt, and social control that is rooted in, builds upon, and reproduces economic and racial inequality and oppression. And it will be communities—the people most directly impacted and those organizing alongside them—that will take it apart. The popular uprisings of the last few years have galvanized defenders to find more and new ways to support that work. Public defenders are marching in the streets, organizing themselves, and finding creative ways to tackle the system.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

But questions about how best to support that work are rarely easy to answer. I and many others have been steeped in them for years. A necessary first step—for which this Gideon anniversary provides an excellent prompt—is to examine not just the history and mechanics of the role of the defender, but to look inward and examine its fundamental goals.

Gideon is a rallying cry for defenders. It offers community, camaraderie, and points toward a shared value: We care about the people the criminal legal system devours and devastates.

At Inquest, we are also marking this anniversary, but without the rallying cry; there are important prefatory questions that must be addressed first. Not just What is Gideon’s legacy? Or What has been Gideon’s impact? But, zooming out, how are we defining impact?

Because to declare progress, we would have to know what the progression is toward.

Defending the “procedural and substantive safeguards designed to assure fair trials” was part of my daily work as a public defender. That mattered; it continues to matter deeply in the daily lives of people experiencing the system. But even if all of those safeguards were defended fully, and all trials were as fair as they could be, public defense clients would still not necessarily be experiencing justice. Why were they there in the first place? What kind of trauma did the experience itself inflict on them, their family, and their community? What would be the aftermath? And what role could a defender play in challenging the system that put them through that? That would put future clients through that?

There is no question: Having good, resourced counsel has deeply positive effects on the lives of the people ensnared in the criminal legal system. We know this from qualitative data, quantitative data, and common sense. There is critical value to that work—especially in this era of massive criminalization and incarceration. Public defenders help to reunite families, expose and challenge police and prosecutorial abuses, and explain to judges why long sentences harm while making us no safer. Public defenders, especially those who handle appeals, can help change laws. Defenders serve a powerful function in a system rife with structural racism that feeds on social control and punishment. Defenders do all of this while outrageously overburdened and under-resourced—because, despite the pronouncement of Gideon, no meaningful roadmap was ever provided to actually implement organized and funded public defender offices across the country.

And yet. It can also be simultaneously true that the deeply positive effects defenders have on a daily basis will not, on their own, help to dismantle mass incarceration. Indeed, they may even facilitate a collective turning away, a widespread diminution of our imaginations about what is possible. As long as we provide lawyers, it will all be fair.

As law scholar Paul Butler writes, Gideon sells the comforting lie that all that is needed is to guarantee that “every person accused of a crime [has] an excellent lawyer.” In a redux of his classic article “Poor People Lose,” penned specially for this Inquest series, Butler pulls the rug out from under this naïve hope: “Gideon created the false consciousness that criminal justice would get better. It actually got worse. Even full enforcement of Gideon would not significantly improve the wretchedness of U.S. criminal justice.”

Butler’s critique is heavy. It focuses on the question of rights through the lens of the right to counsel enshrined in Gideon. Butler draws on the work of legal scholars who posit that the valorization of rights can actually hinder social change. By declaring something a “right,” the law makes it seem objective, neutral, universally understood and accepted. The question then becomes: Has the right been protected or not? Has Gideon’s promise of a right been fulfilled or not? As a result, discussion stops about what the right was meant to provide, and what values it was meant to embody. It also seems to preempt consideration of whether there are other ways—perhaps better ways—that those goals could’ve been achieved. Celebration of the right muffles these inquiries, pushes them to the side.

Lost, too, is a public process of trying to define democratic goals in the first place. By fiat, the Gideon court simply declared that the goal is for everyone to get a lawyer so that their right to a fair trial is protected. Indeed, the court appears to relish the bloat of our massive criminal legal system, and justifies its delivery of this new right based on it: “Governments, both state and federal, quite properly spend vast sums of money to establish machinery to try defendants accused of crime,” the justices wrote, explaining why lawyers should now be provided to those defendants.

But what if community members got to define the goals of public defense? What if defenders did? There are myriad potential goals that one could imagine. Indeed, in the wake of Gideon—its identified goal coming nowhere close to addressing the harms of mass incarceration—people have asserted a number of visions of what public defense should be and do. While these share some basic assumptions—respect and dignity are good; lawyers should center clients’ expressed interests; the public should be apprised of the harms of the system; people should suffer less and be able to thrive—there are also vast differences when it comes to ultimate goals. Some reforms aim for better outcomes from the system. Others seek to expand public defense to do more within the system. Still others seek to challenge the system. These goals are not the same, a fact which can be lost in the din of the rallying cry. Some are even in tension with each other. For those seeking broad social change, an important litmus test is whether any proposed change contributes to the goal of dismantling mass incarceration. The symbolism of Gideon can lead us down unexamined paths, galvanizing reform efforts without this preceding inquiry.

This risks skipping the crucial step of asking questions such as: Should public defense be bigger, expanded? Should it be a catch-all for various social services that the state has otherwise declined to provide? What does it mean for the carceral system to grow in this way through public defense?

Consider how these queries can shift our thinking about something like holistic defense, or related reform efforts to add myriad services to the provision of public defense. There can be no question that the experience of individuals is often improved by these supports. More people receive access to housing assistance, benefits, treatment options, and health care, and are thus less likely to face criminalization or punishment. But, in the long term, are people and communities strengthened? Is power built—or depleted? Is the system that created the problems in the first place weakened? Adding more services to alleviate the immediate harms of the system can risk further entrenching the harmful system itself. It may rob attention from tackling the structures that create harm and divert it to helping people better navigate those systems. As though we are saying, It’s OK—the more harm created, the more help we will offer to mitigate it.

This connects to the critique made by community organizer and educator John McKnight in his essay “Services are Bad for People” (1991): “Service systems require clients and community organizations require citizens. That is why service systems are often antithetical to powerful communities.” The essay’s subtitle states it boldly: “You’re either a citizen or a client.” In another of his classic essays, “Why Servanthood is Bad” (1995), McKnight writes, “Peddling services instead of building communities is the one way you can be sure not to help.” Instead, he urges, “Whenever a service is proposed, fight to get it converted into income.”

Another reform effort—one which at first may seem uncontroversial—is to simply increase access to counsel. Again, there can be no question of the tangible benefits for people who are able to access counsel. But the long-term implication could simply be to bring the veneer of due process to more corners of a fundamentally unjust system. In Inquest, law scholar Angélica Cházaro, an expert in immigration and deportation, has argued against the provision of federally funded counsel for immigrants for this reason:

I want to avoid a future where one or two decades from now we are reading reflections on the anniversary of the establishment of federally funded counsel for immigrants in which the authors lament the exponential growth of mass deportation while celebrating the expansion of access to counsel. Indeed, increased due process in the criminal system context provides an example: There was ultimately no contradiction between Gideon v. Wainwright’s 1963 promise of counsel to criminal defendants and the growth of the most incarcerated population in world history in the ensuing decades.

Public defenders possess a diverse set of motivations. Some want to serve others, driven by religious or secular commitments to aid their communities. Some want to win arguments, years of well-honed debate skills now turned toward prosecutors and judges. For others the criminal legal system represents the epicenter of racial justice work. Others want to mitigate the harms of that system, one day at a time. Some want to make it more fair; some want to abolish it. Many may be driven by more than one of these motivations, or other ones altogether.

Many of these personal motivations are worlds apart from each other—as are, for that matter, many of the potential goals of public defense work. And yet, when it comes to popular narratives, these nuances are generally missing. Words like fairness, justice, and equality are wielded inexactly, blurring critical differences. Is the goal to dismantle mass incarceration—or to make it more fair? Does justice really look like a public defense system that relentlessly metastasizes to match the scale of the system’s harms?

Consider some alternative paths. Defenders around the country are increasingly supporting the power of communities through participatory engagement. Defenders are also organizing themselves as a tool to challenge the system; an essay in the coming days will highlight an example of this powerful momentum. Indeed, collective action by defenders could be utilized to shrink, rather than grow, the system—including by seeking decreased prosecutions. But the role of public defense in the work of broader social change will remain challenging to access until we look inward and ask hard questions. We cannot move forward without knowing which way to go—and why.

Having honest conversations, shifting old narratives: these are not dangerous or scary paths, but rather essential ones. In his 1990 essay “The Role of Law in Progressive Politics,” Cornel West wrote, “The role of progressive lawyers not only is to engage in crucial defensive practices . . . but also to preserve, recast, and build on the traces and residues of past conflicts.” Legal historian Sara Mayeux’s Free Justice (2020) provides a rich, complicated history of the origins of modern public defense—including the legal, social, political, and economic motivations that may have guided the Supreme Court at the time of the Gideon ruling. Free Justice does important work to unravel popular narratives of public defense, including narratives of a court doling out capital-J Justice through the delivery of a right. Mayeux describes, for example, how divisions among lawyers themselves laid the groundwork for the gross underfunding that persists in public defense today. Contrary to popular narratives that portray lawyers as firmly on the side of the Gideon-delivered right, and politicians against it, this exploration of contested history helps to remove the gloss of a supposedly unfulfilled promise offered by the Court and allows us to better assess meaningful paths forward.

In this spirit, to mark the sixtieth anniversary of Gideon, we bring you a five-part series of essays (plus an archival reading list) that we hope will spark discussion about public defense. We believe deeply that public defense has the power to make meaningful change—and we also believe that that power will not be fully realized unless old narratives are broken open, differences are acknowledged, and shifts are made. There can be camaraderie, love, and support while also asking hard questions and embracing complicated truths; in fact, doing so would be the best way to express those things.

This is how we celebrate. Happy anniversary.

Image: National Archives/Inquest