In July, a coalition of 17 health, environmental, faith, labor, student, racial justice and immigrant rights organizations filed a civil rights complaint with the Department of Homeland Security on behalf of 15 individuals currently or formerly detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement at the Baker County Detention Center in south Florida. First-hand accounts from the 15 detained at Baker, who are predominantly from Caribbean Basin nations, detail an egregious pattern of verbal and physical abuse, racism, medical neglect, and retaliation, corroborated by over 100 other people also detained at Baker.

One complainant, Eric Martinez, testifies to being assaulted by county guards at Baker in 2019 as they placed him in solitary confinement, breaking his nose. While in solitary, Martinez went on hunger strike in protest of this abuse, inviting further taunts and retaliation until he was ultimately deported. This was not an isolated incident. In May 2022, guards punished migrants participating in a hunger strike by shutting off access to water and medication, placing strikers in solitary confinement, and deporting others in alleged retaliation. Now living in Colombia, Martinez still organizes with the South Florida Immigrant Action Alliance. In a press release announcing the filing of the multi-individual complaint in July, he sums it up: “This is a place where ICE and Baker County try to cover up their abuses.”

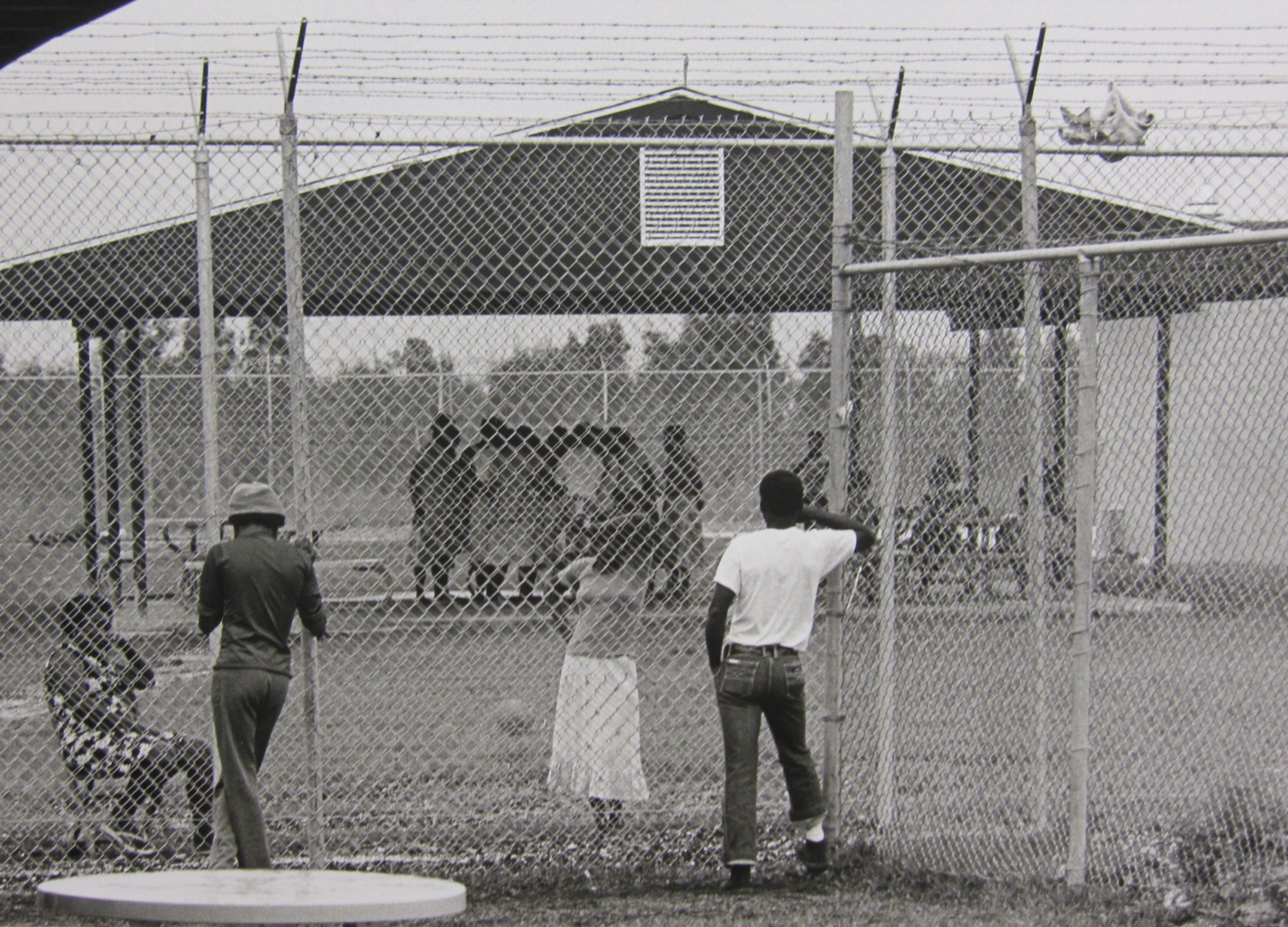

Over the last four decades, immigration detention rates in the U.S. have increased a thousand-fold, and in early 2020, some 55,000 people were incarcerated in immigration detention each day. Over the last two years, the COVID-19 pandemic has curbed admission rates, but it has also worsened already-horrific conditions in detention centers, sparking a new wave of hunger strikes and bolstering the growing movement to #AbolishICE.

And yet, border reporter John Washington, whose work has exposed systemic reproductive and sexual violence in detention in recent years, laments that these abusive conditions never seem to settle into our collective consciousness. Nor do they seem to spark change. “This is the current reality of immigration detention, the reality we have grown used to — at once shocking and any old day.” Are we inured by repetition, he asks? Or worse, resigned to the status quo?

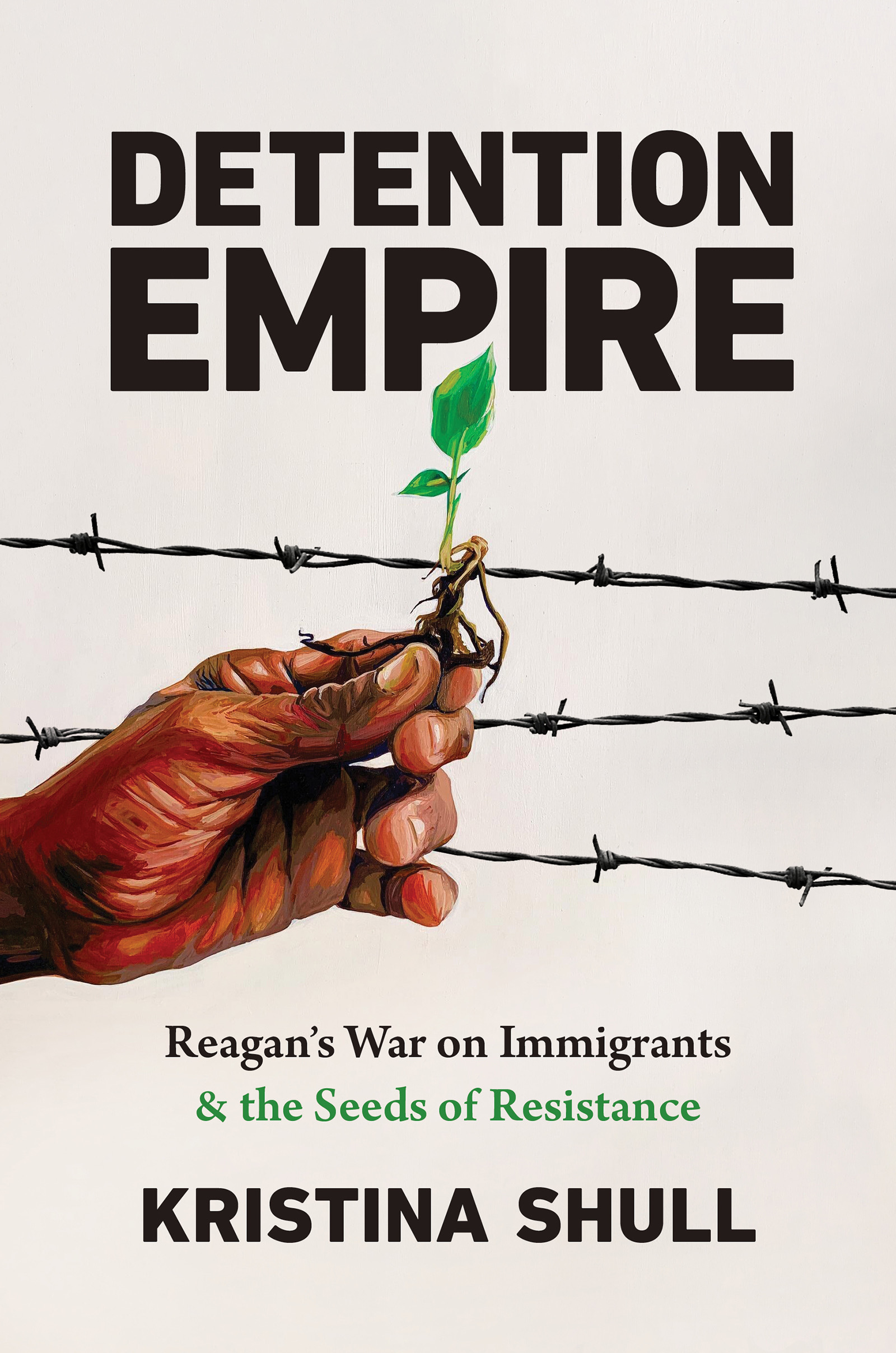

My forthcoming book, Detention Empire, zeroes in on the early 1980s as a critical turning point in the rise of mass incarceration. An event known as the Mariel Cuban boatlift, a large-scale migration of 125,000 Cubans to south Florida during the summer of 1980, alongside increasing arrivals of Haitian and Central American asylum-seekers, galvanized new modes of covert warfare in the Reagan administration’s globalized war on drugs. Demonstrating how detention operates as a form of counterinsurgency at the intersections of U.S. war-making and domestic crime-fighting, Detention Empire traces the Reagan administration’s development of retaliatory enforcement measures to target a racialized specter of mass migration. Laying the foundations of new forms of carceral and imperial expansion, these measures included the systematic detention of asylum-seekers, drug and immigrant interdiction programs, the militarization of a more broadly imagined U.S. border, and prison privatization.

Counterinsurgent, or counterrevolutionary, warfare has a long, racialized history in the United States. It is deeply embedded in U.S. foreign policy and its interventions in Latin America, which have collectively helped to shape contemporary migration patterns. As historians have shown, the United States’ embrace of counterinsurgency has also underwritten retaliatory prison and policing trends at home. Rachel Ida Buff notes that during the Cold War, deportations became a form of “domestic and international counterinsurgency, enforcing the postwar global racial capitalist order.”

In the book, I define empire as the state’s commission of transnational violence in order to sustain itself. Such violence takes many forms, including war and political violence; poverty via labor and economic coercion; race, sex, and gender-based violence; ecocide; and theft of Indigenous land and sovereignty. As multitudes of violence set in motion by histories of U.S. imperialism manifest in scales of migration, detention exacts violence on the scale of migrant bodies. More than a set of administrative practices, detention is a place where the violent ends of U.S. empire are reified and then rendered invisible.

As multitudes of violence set in motion by histories of U.S. imperialism manifest in scales of migration, detention exacts violence on the scale of migrant bodies. More than a set of administrative practices, detention is a place where the violent ends of U.S. empire are reified and then rendered invisible.

Detention Empire challenges two popular misconceptions about the Reagan administration: First, that it was soft on immigration; and second, that Reagan’s right-turn faced little public protest. Reading beyond government archives that tell an “official” story that renders state violence anodyne and casts migrations and social movements that challenge state power as a threat, I draw on community-created, “unofficial” archives, protest artifacts, and oral histories to show how migrants resisted repression at every turn. People in detention and allies on the outside — including legal advocates, Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition, and the Central American Peace and Sanctuary movements — organized hunger strikes, caravans, and uprisings to counter the silencing effects of incarceration and speak truth to U.S. empire.

Reagan’s Carceral Palimpsest

My former husband Andi was the first to point out the inherent contradictions written into the detention system, as when ICE’s Notice to Appear arrived in the mail this was, he joked, his “notice to disappear.” When I visited him in detention, I met with other spouses, siblings, parents, children, and friends. Together, we pieced together what was happening inside. “Recreation” in a bare room, a “law library” without books, a 9/11 mural in the visitation room painted “voluntarily” by detained migrants. Never Forget. We swore to tell our stories, maybe even write a book together. But as each of our loved ones left the detention center, we never heard from one another again.

In both official and unofficial archives, I encountered ongoing dialectics of resistance and retaliation that mirrored my own witnessing and work with people in detention over the past 15 years. And I was struck by how repetitive these patterns were across time and place. I saw how detention was both a site of solidarity and silence.

Over time, intertwining U.S. settler-colonial and imperial projects have laid foundations of what I call the carceral palimpsest. A term in textual and architectural studies referring to inscriptions of new writing or design practices over old ones that still remain visible, palimpsest is a helpful concept for understanding how material and textual, old and new features fuse and function together across detention sites.

The dialectic character of resistance and retaliation in detention is, at heart, a battle over truth. In my book, I was inspired by James C. Scott and Robin D.G. Kelley’s conception of hidden transcripts of resistance, which show how grassroots organizing shapes decision-making at the top levels of government. As protests from detention, amplified by inside-outside and coalitional organizing, met increasing state retaliation, the Reagan administration crafted enforcement policies — and a prose of counterinsurgency — to obscure the impacts of U.S. foreign policy and silence opposition. The result of this ongoing process of erasure is a collective amnesia and a totalizing narrative of “migration crisis” that limits our political imaginations, one that strengthens reformist reforms and only further entrenches border carcerality.

Few presidents are better known for their masterful rhetoric and ability to define themselves in opposition to their enemies as Ronald Reagan. As governor of California from 1967 to 1975, Reagan developed a revanchist politics that responded to actions by the civil rights, student, anti-war, and labor movements. Once in the White House, the Reagan administration drew upon these prior battles to wage a new war on migrant rights.

Reagan’s administration touted the United States as a “beacon of freedom” that embraced refugees fleeing communism, while at the same time giving nods to vigilante violence in the borderlands and U.S.-backed Central American civil wars. Reagan’s targeting of the Caribbean Basin, a region he dubbed the United States’ “third border,” strategically merged immigration control with criminal and communist threats, Cold War geopolitical strategy, and neoliberal designs. Anti-Blackness and homophobia surrounding Cuban and Haitian migrants also converged with Reagan’s dog-whistle signaling on race, deviance, and crime that predominantly targeted African Americans. The Mariel Cuban migration took on mythic proportions as this singular event became an enduring symbol of migration crisis, shaping policy even into the Trump administration.

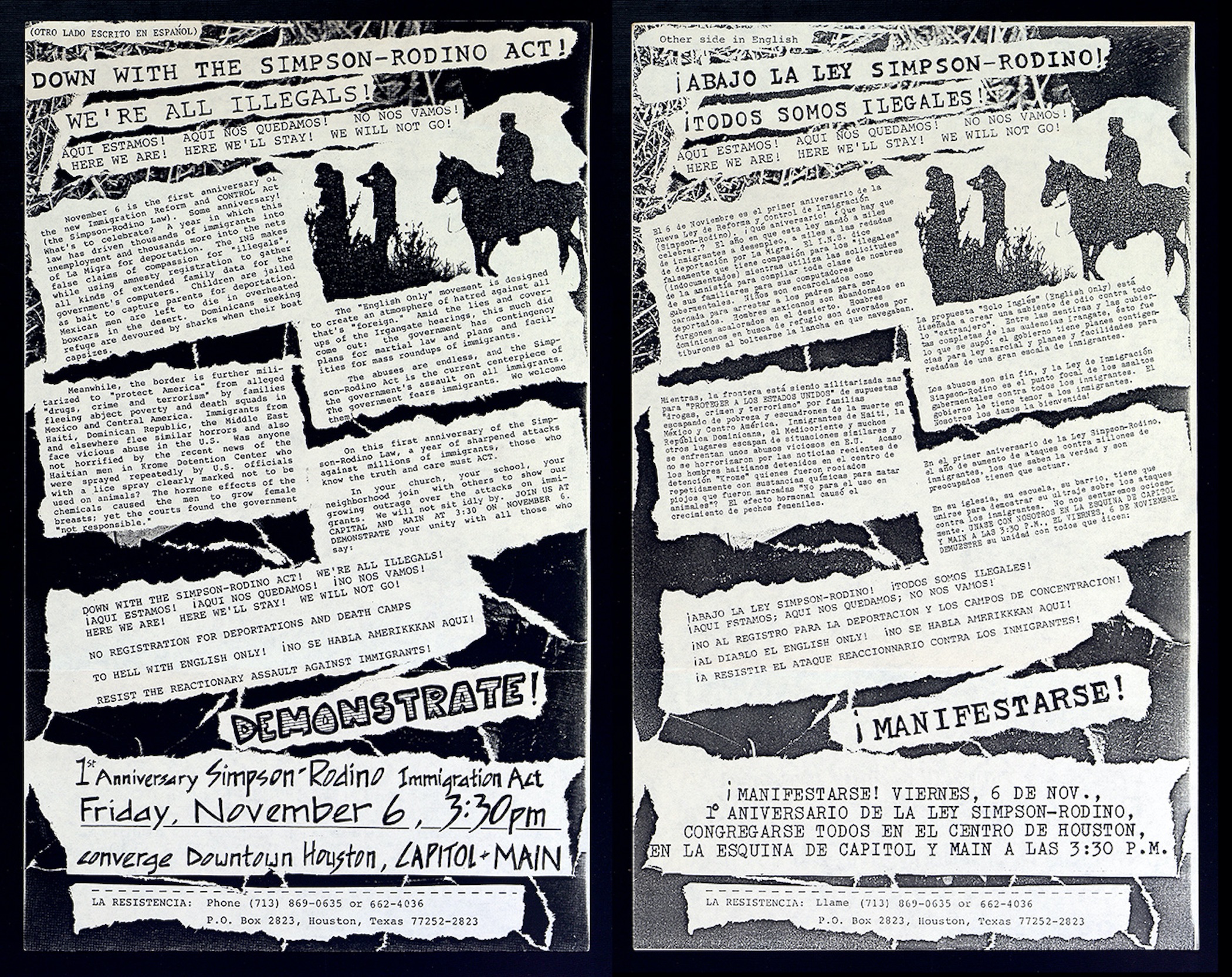

As Reagan’s associate attorney general, Rudy Giuliani was the architect of new detention policies that hastened crimmigration trends, including the administration’s 1982 Mass Immigration Emergency Plan. Tailored to a “Mariel-Type scenario” and further justified by increasing arrivals of Haitian “boat people” and Central American “feet people,” this contingency plan for establishing detention space for 10,000 to 20,000 migrants in the event of a migration crisis would serve as a blueprint for detention building across the U.S. sunbelt.

Inside Strategies, Outside Agitators

Piecing together hidden transcripts, Detention Empire connects landscapes of resistance against the Reagan administration across detention sites. Detained Cuban, Haitian, and Central American migrants wielded their bodies and voices to reclaim freedom and hold the state accountable for its abuses.

Personal and collective protest took various forms, from letter-writing, public petitions, and class action lawsuits; to creating alternate worlds through art, song, and poetry; to coordinating hunger strikes and riotous unrest. In 1987, Mariel Cubans subjected to years of indefinite detention staged a takeover and standoff at two prisons in Atlanta and Louisiana spanning 15 days — the longest prison uprising in U.S. history.

Ongoing resistance created pressure within detention, while transnational solidarity activism opposing Reagan’s foreign policies drew connections between conditions of confinement and global freedom struggles. This was seen in U.S.-Cuba student solidarity formations and advocacy on behalf of queer and trans Mariel Cubans detained on U.S. military bases; in the feminist journal Off Our Backs, which supported Haitian women on hunger strike in facilities across the country; or in Salvadoran and Guatemalan refugee caravans and “speech acts” mobilized by the Sanctuary movement. Off Our Backs published a message from one Haitian woman imprisoned in Alderson, Kentucky, to the U.S. government: “We have our hands and our bodies and our minds. In the death that they want us to have so much, we know life. You tell them they can never take that away from us.”

Along with masterminding new immigration policies, Giuliani also played a pivotal role in developing retaliatory measures and a rhetoric of counterinsurgency aimed at neutralizing Reagan’s opponents. After a hunger strike at the Krome Detention Facility in Miami that drew international media attention and coalitional protests led by civil rights leader Jesse Jackson, the now-defunct Immigration and Naturalization Service called in the Bureau of Prisons to help form a militarized Border Patrol Tactical Unit (BORTAC), while Giuliani directed the INS and the FBI to monitor “outside agitators.” These scripts would play out again on a larger scale as these agencies harassed and prosecuted Central American peace and Sanctuary movement activists, aided by Reagan’s issuance of Executive Order 12333, which legalized domestic surveillance “in support of national foreign policy objectives abroad.”

Giuliani monitored internal and public communications surrounding detention, refuting migrant and allied accounts of abuses in detention. Traveling to Haiti, he even forged diplomatic relations with François Duvalier’s regime to lay groundwork for the Haitian interdiction program and justify the United States’ blanket rejection of Haitian asylum-seekers.

The preemptive logic of the Mass Immigration Emergency Plan extended to stifling domestic dissent. In 1987, amid revelations of Reagan’s Iran-Contra scandal and months before the Mariel Cuban prison uprisings, the Miami Herald broke a story about a highly classified government plan developed three years earlier called Rex84. Authored by FEMA director Louis O. Giuffrida, head of Governor Reagan’s Specialized Training Institute in California, and Oliver North, Rex84 was a scaled-up contingency plan for suspending the Constitution in the event of wide-scale crisis — specifically, nuclear war, nationwide civil uprisings, or mass migration — sparked by the U.S. invasion of Central America. Originating in Giuffrida’s thesis advocating for martial law and recommending “relocation camps” for millions in the event of a national uprising of militant Black nationalists, Rex84 included plans for detaining up to 400,000 undocumented immigrants. Rex84’s civil rights-era origins reveal the tenor and anti-Black roots of Reagan’s counterinsurgent, carceral logic.

Abolitionist Imaginaries

That mounting protests from detention and the Sanctuary movement raised such alarm within the Reagan administration as to inspire plans such as Rex84 is instructive — both as a cautionary tale and for its abolitionist potential.

As I researched Detention Empire over more than a decade, I began working with communities to document, archive, and mobilize stories from detention that defy prisons and borders — and the prose of counterinsurgency that sustains them. Coalitional efforts to document abuse and reverse erasure are crucial for building power and reckoning with the enduring xenophobia driving detention policies today. In July 2022, immigrant rights advocates in South Florida also celebrated a victory — ICE’s decision to stop use of the Glades County Detention Center. Having organized with the Shut Down Glades Coalition over the past year and a half, Eric Martinez reflects: “It was an amazing feeling to raise up the voices of those in detention … what is done in the dark should come out to light. It was a great pleasure to be part of that light.”

However, recovering and documenting stories may not be enough. As a movement tactic, storytelling has been critiqued for lacking historical context, contributing to narratives of victimization or deservingness, and sustaining neoliberal agendas. Indeed, some of the most radical critiques of the Sanctuary movement came from within.

Alejandro Rodriguez was a labor organizer who experienced torture at the hands of US-backed death squads and fled El Salvador with his family to enter Sanctuary in Rochester, New York. Named an “illegal alien co-conspirator” in a 1986 federal trial against Sanctuary movement leaders, Rodriguez was forced to testify or face deportation, yet not allowed to tell his migration story to the jury. Censored by the U.S. government, but he also had a message for his co-conspirators. Speaking from sanctuary in 1985, he described his desire to “deepen the work until the movement becomes more aware of itself and its people, with a real expression of its historic roots. There is little vision of the work directed in solidarity with the people who are truly suffering repression. This manifests itself when you ask for a message without content.” Others in Sanctuary also urged allies to see it as a process of political education, and of learning to make way for migrant voices and leadership.

Detention Empire asks: What can grow from seeds of resistance already planted, and their interconnecting roots? I conclude that to end detention, different conceptions of migration are necessary, aided by abolition feminist and critical refugee studies scholarship that reject the premise of state sovereignty and foreground migrant journeys and lifeworlds as sites of critique, decolonization, and reparation. Stories from detention expose cracks in the architecture of detention itself. Placing them alongside one another across time and place — to build solidarity across groups and contexts — can dismantle its foundational logic in its entirety.

These visions are not new. As Alejandro Rodriguez concluded in 1985: “The sanctuary movement must take the next step, which is a historic step: to forge an anti-investment solidarity movement.” Ultimately, he was asking U.S. audiences to divest from complicity in empire in all its forms.

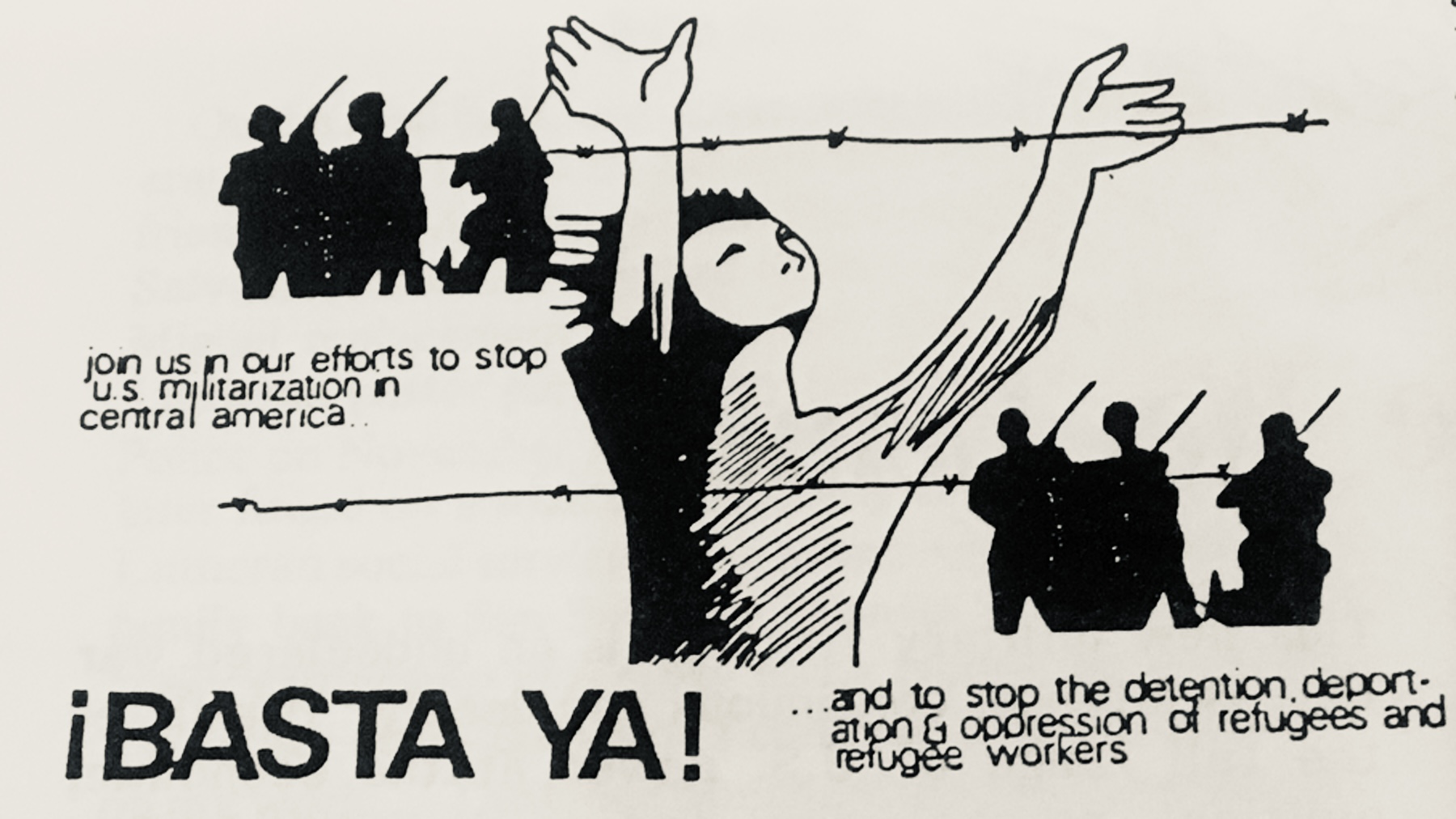

Header Image: Basta Ya! Image in “Sanctuary: A Justice Ministry,” Chicago Religious Task Force on Central America, 1985. Used by permission of Renny Golden.