Before the 1960s, there was no such thing as “prisoners’ rights.” At that time, federal courts paid allegiance to a hands-off approach when it came to individuals in state prison; judges abstained from interfering with state punishment practices. Moreover, there was still no nationwide ban on cruel and unusual punishment during this period, which meant that people in prison had practically no power to challenge their conditions of confinement. The era, while bleak, was still not as bad as earlier times when incarcerated individuals were considered “slaves of the State,” as the Virginia Supreme Court described in Ruffin v. Commonwealth.

It was out of this history of hard times that a prisoners’ rights movement was born. In this struggle, Muslims became a force in forging a path for people in prison to sue for civil rights. It was followers of the Nation of Islam who began the major push toward establishing rights for those in prison, which finally broke through in Cooper v. Pate. That 1964 case was a watershed moment in American prison history, since it marked the first time the Supreme Court cleared a way for federal courts to hear complaints by people in state correctional facilities. While the ruling was based on the religious grievances of Nation of Islam followers, the decision was monumental for all individuals in prison.

Since those days, there have been demographic shifts in prison. For example, the influence of the Nation of Islam has waned with the growth of Sunni, Shia, and other denominations in prison demographics. However, decades of ongoing litigation demonstrate a unique commonality among these groups — a shared affinity for court action. The sheer magnitude of lawsuits by Muslims in prison suggests something unique is occurring, or perhaps two unique things are happening together. On one hand, Muslims may sue in greater numbers because they are actually treated more harshly than others in prison; on the other is the force of religion, which drives the litigation in singular ways as well.

Islamic Attitudes Toward Justice

Prominent in Islamic traditions is the value placed on pursuing social justice and equality. As one adherent put it in an early volume of Muhammad Speaks, “Justice is an attribute of Allah Himself.” The Muslim faith puts a premium on justice, which makes the pursuit of justice synonymous with one’s duty as a Muslim. These ideals provide a theological frame for understanding attitudes in the prison context.

Scriptural references in the Qur’an abound with exhortations to treat others justly and seek justice for others. Verses extol that alongside the worship of God, one should show kindness toward disenfranchised groups and stand for justice even against other Muslims: “O you who believe! Stand out firmly for justice, as witnesses to Allah, even as against yourselves.” Resisting tyranny and looking out for the safety and sanctity of one’s fellow humans are recurring themes in the Qur’an. Those who stand up to oppressors are likened to saviors sent by the grace of God:

And what is it with you? You do not fight in the cause of Allah and for oppressed men, women, and children who cry out, “Our Lord! Deliver us from this land of oppressors! Appoint for us a savior; appoint for us a helper—all by your grace.” Believers fight for the cause of Allah, whereas disbelievers fight for the cause of the Devil. So fight against Satan’s forces. . . .

As the statements propound, standing for justice and standing against subordination is God’s work, for as described in the Qur’an, “Allah commands justice, the doing of good. . . .” By contrast, the Qur’an lays out over two hundred admonitions against injustice.

There is a strong emphasis on racial justice in the Qur’an and other traditional sources. One prominent notion is that “everyone is born a Muslim,” a principle of equality that lays out humans as equal from the beginning. Traditional works describe skin color as akin to the colors of clay in the earth — black, brown, and white — all of which is a sign of divine creation: “Among His signs is the creation of the heavens and the earth and the diversity of your languages and your colors. Verily, in that are signs for people with knowledge.” As such passages indicate, there is meaning in the fact that people come in different colors and cultures.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

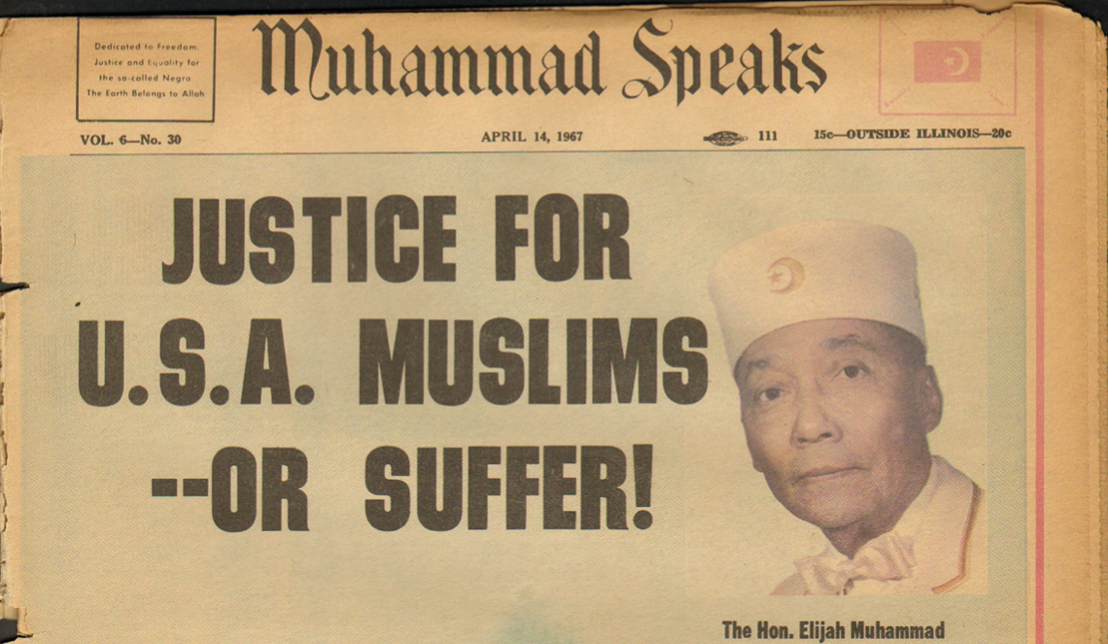

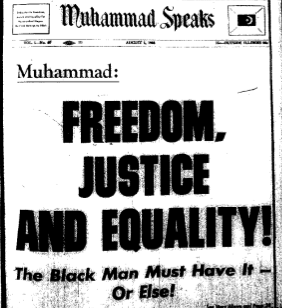

In the years of the civil rights movement, members of the Nation of Islam were at the forefront of advocating for justice for Black Americans. Muhammad Speaks, for example, adopted slogans like “A Militant Monthly Dedicated to Justice for the Black Man” and “Justice and Equality for the so-called Negro.” The paper’s back cover often lists the organization’s core tenets, including, “We believe in justice for all, whether in God or not; we believe as others, that we are due equal justice as human beings. We believe in equality — as a nation — of equals. We do not believe that we are equal with our slave masters in the status of ‘freed slaves.’” As this creed indicates, justice is such a strong commitment that even those who identify as atheists should receive it.

Other writings in this publication strike at the heart of what justice means to followers. Consider “The ABC of Divine Knowledge,” which situates justice as a divine attribute:

J is for justice.

Justice is equality.

Justice is freedom and peace.

Justice is part of the Muslim’s divine faith.

Every Muslim believes in justice.

Justice is an attribute of Allah (God) Himself.

Allah is the most justice.

Justice is Good.

Without justice, nothing can be good.

The devil knows no justice.

The devil is the enemy of justice.

That is why there is no good in the devil.

I do not like the devil.

I do not like those who do not believe in justice.

The poem identifies Allah with justice, which is the enemy of the Devil, drawing cosmic battle lines that legitimize the taking of earthly action. In this struggle, justice is the central tenet, as described in “Up You Mighty Nation”:

Rise up and shine you mighty sons, For gods you were born and will die; The Muslim cry is Justice For Allah we live — we die.

This sentiment continues to the present. For example, one traditional saying has become a central reference for Muslim justice advocates and organizations in the United States. The saying proclaims:

Whosoever of you sees an evil, let him change it with his hand; and if he is not able to do so, then [let him change it] with his tongue; and if he is not able to do so, then with his heart — and that is the weakest of faith.

This passage holds the taking of action against injustice as an indication of the strength of one’s faith. As Sahar Aziz notes, while the maxim to oppose evil “is frequently interpreted as a mandate against injustice and oppression, it inspires many Muslims in the United States to defend civil and human rights at the local, state, national, and international level.” In addition, Muslim student associations across the country invoke this saying in their calls on members to defend certain causes, including joining campaigns against sexual assault on campus and Black Lives Matter. As one individual in a Missouri state prison described:

For every Muslim, enjoining what is right and forbidding what is wrong is the key to fight for truth and justice. It is an Islamic concept and practice [that] permeates the soul of every true believer. It doesn’t have to be an Islamic matter, but any injustice, and we are commanded to fight oppression until no more oppression exists. Not in a violent manner, but in a peaceful way.

Religion’s Influence on Litigation

While the Muslim contribution to the prisoners’ rights movement and prison litigation beyond has been noted in scholarship, little is known about the impacts of these religious ideas on litigation. My forthcoming book, Muslim Prisoner Litigation: An Unsung American Tradition, details how religion has influenced litigation efforts. The work explains how religion profoundly influences litigation at multiple levels of analysis.

One obvious way is when a lawsuit centers on a religious issue. In these instances, the individual’s ability to practice religion may be at stake. Whether it be the inability to fast for Ramadan or congregate for prayer, curtailments of religious freedom may cut at the heart of one’s beliefs and practices.

Less obvious is how religion influences through the organizing efforts of groups and individuals. Muslim organizations have orchestrated lawsuit efforts and spearheaded litigation campaigns. For example, in the 1960s, the late Martin Sostre, the famed jailhouse lawyer, litigated numerous cases, including some that had lasting impacts. He believed that pen and paper were weapons in the fight against Satan and was known for taking great risks to create and circulate templates that other litigants could use for their court filings. He was virtually a one-man army who worked to streamline litigation.

Religious conversion is another factor that bears on litigation. As a general matter, converts are known for possessing boundless energy and zeal for their newfound faith. Converts to Islam are no exception, and many have focused their energies on litigation. Moreover, converts may be particularly sensitive to curtailments on their newfound faith and be especially willing to take on the risk and burden of a lawsuit.

Lastly, religious ideology itself may factor directly into litigation efforts. In such instances, traditional messages of Islam, like those described above, are a motivational force to take court action, the likes of which are described below.

Spiritual Activism through Litigation

You asked what motivates me to litigate: Justice and the taking of power from oppressors who seek to destroy Islam by watering it down. Islam enjoins the right and forbids the wrong, so . . . as righteous Muslims we have a duty to resist and disobey. So our form of resistance at the present time is court action. —Gregory Holt aka Abdul Maalik Muhammad

Despite that Muslims make up less than 2% of the American population, collectively, they sue in numbers that make them the most litigious religious group in prison. One might even be tempted to say that Muslims sue “religiously,” which is not off the mark. For some, the inspiration that motivates litigation comes directly from religious scripture, tradition, and practices. When one considers the above quote from the plaintiff in the Supreme Court case Holt v. Hobbs, it becomes clear that religion and litigation sometimes share a causal relationship. I have used the term “Muslim litigiosity” to describe how religion directly informs and animates lawsuits. Referring to the above saying, the plaintiff in Holt explains, “This form of action is one of the means of resisting oppression that the hadith refers to when it states that you can fight oppression by using your tongue.” As such, his work as a litigator fits squarely within his understanding of Islam:

Lawsuits surrounding Islamic issues are also a form of dawah or calling because it educates the non-Muslims about what true Islam is . . . . I believe that when I stand before Allah (swta) on the Day of Qiyam, when I receive my Book of Deeds inshallah in my right hand, that my actions here will be the things that allow me to run across the Sirat bridge into Paradise. As Imam Jamil Al-Amin said: I seek truth over a lie, I seek justice over injustice, and I fear Allah (swta) more than I fear the state.

Understanding this religious dimension of litigation helps to make sense of the fact that Muslims sue in disproportionately large numbers. Of course, this reality does not mean to undermine the lawsuits that arise directly due to discrimination and repression visited upon Muslims in prison; genuine misconduct by officials also causes individuals to seek remedy in court. Yet to the extent these overlap, there is a clear indication that some individuals are guided by spiritual ideals. As one individual in Florida state prison describes:

What inspired me is my faith. How even though I’m Muslim & others are not. Islam (Quran & Sunni) still tells Muslims to stand up for the right even if they are not Muslims. So I always felt, whatever I win on behalf of Islam, the non Muslims can even benefit.

As such statements suggest, what religion does behind bars is more than what has been previously understood; for Muslims, faith mobilizes individuals and inspires them to take up the perilous work of going to court, which is no easy thing while incarcerated. Individuals are subject to further mistreatment for reporting the misconduct of their keepers, and individuals have been targeted for retaliation by prison staff. Still, despite these and other perils, Muslims continue to march to court in steady numbers, never mind that most legal claims will be unsuccessful. An individual in a Georgia prison supports the point, describing that “Islam played the only role in filing my [religious] claim. . . . Islam commands all Muslims to stand against oppression to fight in the cause of the religion (not a physical fight), not to mention my rights secured by the federal constitution to do so as well.”

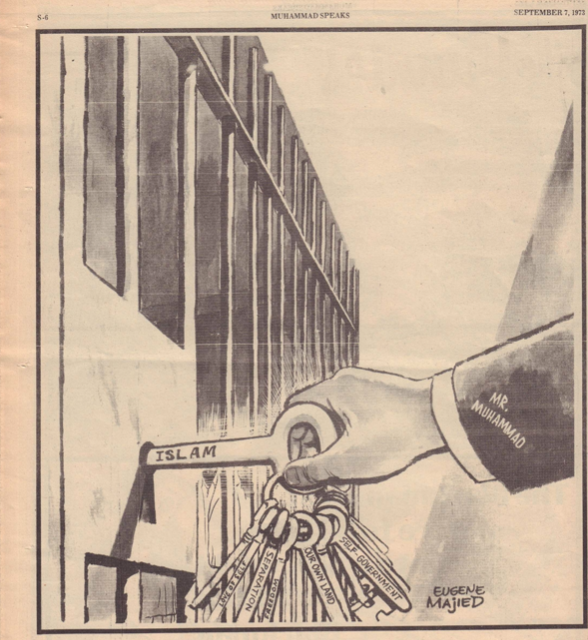

The notion that religion is an impetus for litigation might strike some as novel, but it has been evident among Muslims from the early years of litigation to modern-day efforts. In prison, individuals like Sostre connected their acts in court directly to ideology. From his perspective, because pens, papers, and notebooks could create court petitions, they were like “dynamite” and were imbued with spirituality as the “most essential weapons to fighting Shaitan.” In a 1967 Muhammad Speaks article, one individual describes how justice was the driving force of his undertaking: “The main thing I would tell them was how the Muslims wanted freedom, justice, and equality and unity of the Blackman. . . .” More importantly, he saw the law as the best way to continue his struggle:

The only way I could win was to fight him with his own weapon which was law enforced by the state and Federal Government. I began studying State and Federal law. As I studied I wrote petitions seeking religious privileges in order to hear a Muslim Minister speak the word of Islam. I filed petition after petition, but in each court it would lose. So I began writing. I even wrote for other prisoners — getting them out of prison and back home again.

Although these sentiments were expressed decades ago, they have modern iterations, as another describes:

I believe that I have been commanded to fight to establish Allah’s Religion if it is being oppressed from its establishment. In the prison environment, the pen is the mightiest weapon given to an inmate. As a martial artist in Wing Chun and Ti Quan Do martial arts, I have mastered the art of writing as a means of self-defense technique against the prison administration. I only fight (write) when I am forced to.

Such individuals reflect the essence of Muslim litigiosity — they are willing to take great risks to litigate, sometimes even learn the law and how to write, and fight against injustice for themselves and others.

While many may be familiar with devotional acts like fasting and performing rituals, Muslim prison litigation forces us to reimagine the role of religion in prison. This phenomenon challenges conventional notions about religious expression and experience and makes it a mistake to associate litigation with the mundane. As some cases clearly indicate, bringing a court action may embody the essence of spiritual consciousness, which makes Islamic justice a foundation from which prison reform has been building for decades.

Header image: April 14, 1967 front page of Muhammad Speaks. (Image courtesy of author.)