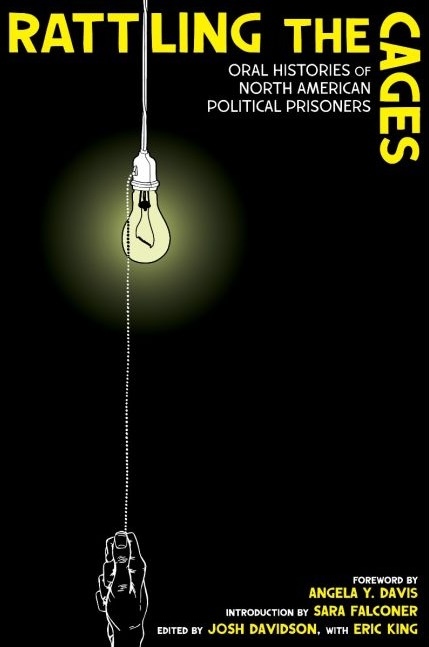

Officially, the United States has no political prisoners. But the reality is a different story. Rattling the Cages is a compilation of oral histories from three dozen current and former political prisoners. It provides firsthand details of prison life and the political commitments that continue to lead incarcerated people into direct confrontation with state authorities and institutions.

The following excerpts, adapted from the book, are drawn from the oral histories of three individuals: Jalil Muntaqim, a former Black Panther; Martha Hennessy, a peace activist in the Catholic Worker Movement; and Xinachtli, who came to identify as a political prisoner during the course of his incarceration. Their principled resistance in the face of the unimaginably cruel and tortuous conditions they survive speaks volumes to their character.

Their stories and experiences also serve as examples of the inhumanity of the carceral system and the depravity that the state embraces to maintain power. The fact that these interviews are filled with love, compassion, concern, empathy, and hope—with humanity itself—shows that no level of carceral torture can kill the revolutionary hope for a better world.

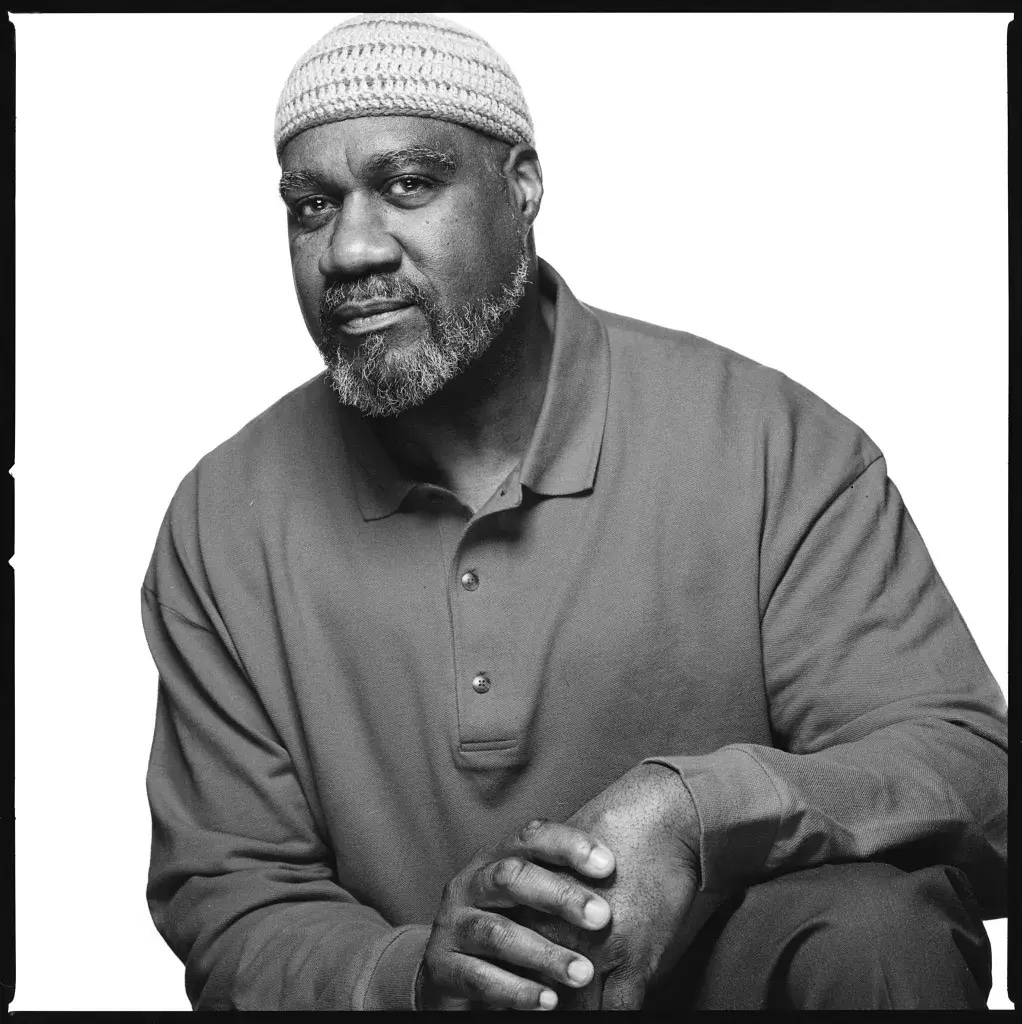

Jalil Muntaqim

Jalil Muntaqim became affiliated with the Black Panther Party at age eighteen. Less than two months before his twentieth birthday, he was captured with Albert Nuh Washington in a midnight shootout with San Francisco police. He was subsequently charged with a host of revolutionary activities, including the assassination of two New York City police officers. He was imprisoned for forty-nine years in numerous maximum security facilities in both California and New York and was released in October 2020. Jalil has published two zines—On the Black Liberation Army and Letters From Jalil Muntaqim: Reflections From Inside Prison Walls on Resistance to Police Terror—and two books—We Are Our Own Liberators: Selected Prison Writings and Escaping the Prism . . . Fade to Black: Poetry and Essays.

*

I’m a former member of the Black Panther Party (BPP) and the Black Liberation Army (BLA). I was arrested on August 28, 1971, in San Francisco. It was basically a shootout with cops, and they captured me and my comrade Nuh [Albert Washington], who passed in 2002 of cancer in prison. We were charged with a host of cases as a result of our activities within the BPP and the BLA. As a result, I was sent to prison from the age of nineteen, and I was released in October of 2020. That’s about forty-nine years and a few months in prison.

I have always had family support. My family was always there. But there were times when I didn’t have community support or outside support from organizations and so forth. You have to remember that at the very beginning, especially after the more militant development of the struggle had diminished, there was no more “Free Huey!” or “Free Angela.” No more “Free the Chicago 7” or the New York Panther 21. As soon as those cases died down, then the idea of political prisoners, for the most part in public narrative, became extinct. There was no discussion or talk about political prisoners to any large degree. For the most part, a lot of us in the early years, in the 1970s and 1980s, we had to fend for ourselves in terms of our own subsistence. It wasn’t until I began to organize the Jericho Movement in 1998 that we started to get a real, serious federation of friends and supporters who began to give recognition to the resistance of political prisoners.

We need to increase our capacity to highlight the existence of political prisoners inside prison. Use all of our print, digital, and social media platforms to raise the idea that political prisoners exist in the United States and that they should be supported. Also, in doing so, we have to raise the question of why there are political prisoners. This supports the overall struggle itself, which political prisoners evolve from and respond to.

We need to build and strengthen a prison abolitionist movement. We need to build a campaign like BDS (Boycott, Divest, and Sanction) in terms of a fight against mass incarceration. Any corporation or business that does business with the prison–industrial complex should be boycotted and sanctioned. BDS is important in that regard, so we need to build a BDS movement and take the money out of prisons. Fight the corporations that are exploiting prison labor. Challenge them and raise these questions in the name of political prisoners. If you do so, that’ll be a tremendous help in regard to the issues of building a campaign that is opposing mass incarceration.

Anyone who is concerned about mass incarceration, who is opposed to prison slavery, needs to bring these issues to every struggle. There should not be an issue in the community that is not attached to prison slavery, whether it’s housing, working, or minimum wage. If you’re fighting for a better minimum wage outside of prison, imagine what the minimum wage is inside of prisons. That kind of interlinking of struggles is very important. If we can do that, then essentially you have made that movement whole. You cannot have the organizing of the prison movement, or organizing the workers’ movement, because they go hand in hand.

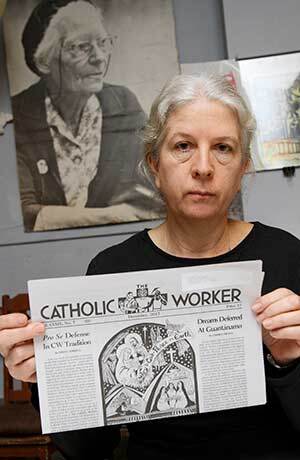

Martha Hennessy

Martha Hennessy is a peace activist and member of the Catholic Worker Movement, which was started by her grandmother, Dorothy Day. Martha has been imprisoned multiple times since the 1980s for her protests again nuclear weapons, drone strikes, and the torture being carried out at Guantánamo Bay by the U.S. government. Most recently, Martha was imprisoned for taking direct, nonviolent, faith-based action for nuclear abolition at the Kings Bay Naval Base in southern Georgia on the fiftieth anniversary of the killing of Martin Luther King, Jr., on April 4, 2018.

*

In prison, everything is dictated to you: what you eat, what you wear, what you do each day. It’s very regimented and yet very dead of things to do and a lot of downtime. But I worked in the library. I refused to do any kind of paid work because I refuse to pay restitution for the nuclear weapons. I took up knitting. They had a guitar there, so I was able to keep up a little bit with my guitar skills. I had a very large mail correspondence.

I think the lack of recognizing us as humans is the most shocking thing. This whole creation of a system where the sole, single goal is to punish and to criminalize. People are more than just what their charges were. The dehumanizing I found to be just so, so shocking. One woman tripping and falling and fracturing her elbow, and the way they treated her. They didn’t give her care, and that was incredibly painful to watch. Without my faith, I would have been more bitter, I would have been more angry, I would have been cursing a lot more. The faith component of it, that’s the tradition that I come from, conscientious objector, Catholics in action. No, I would not have had the presence of mind or stamina without that kind of background.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

For incarcerated people, outside support is critical, crucial. My support people were wonderful, just absolutely wonderful. Not everyone in my family fully understands my faith journey, never mind this nuclear resistance journey. But it’s really, really important to give the prisoner room to express themselves. Make sure they have enough stamps and envelopes. Make sure that you know somebody is staying in touch with them, so they feel like they’re not totally, completely abandoned. Support is so critical.

In prison, you have to hold on to your humanity and realize that you don’t have to scapegoat each other. In terms of advice, just greet new prisoners and introduce yourself. I did this at the halfway house. People would be coming through all the time, and people would be leaving without a word, and I would try and encourage—and other prisoners did this too—people to say goodbye to the folks leaving and introduce yourself to the new ones coming. Just maintain that basic humanity and social skills, if you can. And nonviolent commitment, that’s huge.

We’ve got to change it, we’ve got to change it. We’ve got to care, we’ve got to pay attention, and we’ve got to act.

Xinachtli

Xinachtli (Alvaro Luna Hernandez) is a lawyer and community organizer from Texas. In 1976 Xinachtli was wrongfully convicted, and he was paroled in 1991. Subsequently, in 1997, he was sentenced to fifty years in prison for defending himself by disarming a police officer who drew a weapon on him. While imprisoned, Xinachtli has helped countless people with his jailhouse lawyering, and his human rights work has been recognized in Italy, France, Spain, Switzerland, Mexico, and other countries. In total, Xinachtli has served over forty years in numerous Texas state prisons, usually in solitary confinement, where he continues to fight back against his imprisonment.

*

I became politicized in prison and suffered extreme forms of state repression, including beatings, false disciplinaries, horrible food, prolonged stays in solitary confinement, denial of parole, and being imposed with the label Security Threat Group (or “gang member”) to justify solitary confinement and isolation from the rest of the prison population. This is a policy and practice that continues today here at the McConnell Unit, as I am in a cell block housing the mentally ill, with extreme mental problems, and beyond reach of getting them engaged in the struggle for the defense of their human dignity and their human rights, behind white Amerikkka’s iron curtain, where suppression still remains the order of the day. My incoming and outgoing correspondence and legal and political writings, essays, letters—all critical of institutional racism, of colonialism, capitalism, imperialism, and fascism—continue to be denied.

I think it was Karl Marx who once said that it is for us not to merely interpret the world but to change it. For it is true men and women who make history. My revolutionary politics and my spiritual and intellectual growth and development, and my, if you will, ascendency to the heights of a life of dedication and commitment to the freedom struggles to change the world are what has kept me sane, alive, and never, ever losing hope. Dialectical materialist history is on our side, for we are gravediggers of the old capitalist order and delivering a new one, like a midwife delivering a newborn, but here, from the ashes of the old, rotten, corrupt, and bankrupt society, “pregnant with social revolution.”

When the prison knows that prisoners have strong outside support, I have seen them with my very own eyes back off or be more reluctant to unleash the unvarnished brutalities of its terrorist violence and brutalities against its captive population.

My advice would be to expect a racist and brutal prison regime, especially if you are Black, Chicano, or Native American, and get involved with jailhouse lawyers and demand your basic legal, democratic rights. You will face intense repression that may include beatings, false disciplinary cases, relegation to solitary confinement for long periods of time, horrible food, lack of adequate medical care, no educational, religious, or other self-help programs other than the ones you work to develop with existing “leadership” that is into it (and not into the holy-roller mentality of seeking salvation in religious dogma, or the pie-in-the-sky faith the prison system supports because it serves their own purposes of maintaining good slaves). As long as there exists this capitalist political economy, there will be prisons, for the prison is a pillar of capitalist class relations. Prisoners coming into the prison must discover their humanity and open their eyes beyond the social conditioning we are all subjected to as subjects of a racist and oppressive patriarchal system.

What has sustained and kept me alive has been my revolutionary belief systems which I came to discover through jailhouse lawyering, and from those that came before me, to bring me in, teach me the ropes and guide me in the right direction, to begin seeing myself, the world, and the dialectical sciences that are the destiny of us being the most marginalized and oppressed segments of U.S. society. Because of our condition under neocolonialism, capitalism, imperialism, and bourgeois fascism, we are the motor force for change, and we are the vanguard elements that eventually will lead a social movement from within, demanding changes, and a new society, a new political-economic system that does not exploit the labor power of the workers, and can provide true freedom, justice, and equality that the current capitalism system can never provide.

Excerpted from Josh Davidson and Eric King’s Rattling the Cages: Oral Histories of North American Political Prisoners, published by AK Press, with permission of the authors and AK Press.

Image: Rae Galatas/Unsplash