Guadalupe, a Salvadoran asylum seeker, was seated for an interview in her lawyer’s office in February 2020, dressed demurely in a pink down vest and sweater, a month before the COVID-19 pandemic shut the nation down. She politely described her circumstances. What Guadalupe told was a horrific story: While asleep one Sunday morning, she heard three gunshots. Wanting desperately to believe the sounds were benign, she ran to her brother, who suggested that the noises came from one of the street vendors in her small town who set up stands to sell fruit, pupusas, or clothes. She was not reassured. “I knew in some way that they were gunshots,” she said. Within minutes, a cousin showed up at the house in tears, saying that Guadalupe’s father had been shot and was seriously injured. Running to the park where her father worked each morning, she found him dead. Later, gang members approached her on the street and at the house to warn her that they would kill her and the family if they cooperated with police. “You will end up in black bags,” one gang member said. That left Guadalupe, her mother, and siblings no choice but to migrate to the United States to ask for asylum. Given El Salvador’s small size and the gang’s ability to track people down in neighboring communities and even countries, the United States offered the most safety despite the journey’s distance.

Another woman, Ximena, age twenty-five, fled El Salvador with her four-year-old son after her gang-affiliated partner beat her repeatedly, threatening to cut her tongue out if she told police. Ximena escaped the home they shared to seek safety at her grandmother’s house. Her partner stalked her there, standing outside for hours and threatening to take their son. Ximena grew increasingly alarmed as her son began exhibiting behavior learned from his father, calling her a “whore” and mimicking the gestures and gait of a gang member. One day her son picked up a toy gun and screamed at her, “I’m going to kill you!”

Internal relocation to escape gang or domestic violence usually isn’t an option because of law enforcement corruption and ineffectiveness, as well as the widespread belief—often borne out of experience—that internal relocation won’t provide safety. For women from Central America and Mexico who suffer violence at the hands of a domestic partner or gang member, an application for asylum in the United States proffers hope for survival and a future. Yet while a cliché dubbing the United States a “nation of immigrants” persists, most asylum seekers face a path fraught with legal obstacles.

Over the course of this century, research has probed how laws force migrants into spaces of limited rights and numerous social harms. As a result, there exists an extensive corpus of scholarship delineating how shifting statuses constrict life for those who do not have fully legal status. In their conceptualization, sociologists Cecilia Menjívar and Leisy Abrego argue that fragmented immigration policies such as arrests for unauthorized border crossing or employment restrictions cause suffering across multiple life domains, an accretion of laws and policies they term “legal violence.” Drawing on the work of Mary Jackman, Menjívar and Abrego note that legal violence is inconspicuous as it results from socially accepted policies and practices. Such policies seem routine and reasonable to many Americans because they are the law, although they lead to deportation, social exclusion, tenuous legal status, and violations of rights.

Undocumented immigrants live in a state of legal nonexistence; since they are not incorporated into the nation, mundane tasks such as working require clandestine activity. Asylum seekers exist outside the law while at the same time occupying a hyper-legalized space—one in which laws constrict and limit their life options as they enjoy minimal legal protections but abundant restrictions. Efforts to conform and abide by the law, including completing tax forms or obtaining a child’s birth certificate, expose people with tenuous legal status to risk and immigration enforcement, causing suffering and limiting opportunity.

But how, then, do we conceptualize life choices, legal struggles, and social suffering for women seeking asylum? Winning asylum is a fraught process, and women who seek asylum occupy a space of legal ambiguity and public opposition—a space we call compounded marginalization—as they await asylum hearings. For years, their lives are defined by uncertainty.

Lula, a thirty-three-year-old Salvadoran whom gang members targeted for rape because she is a lesbian, emphasized to us that she wants little from the United States beyond safety:

The only thing I want is to be calm and to know if I am going to be in a place where I can work and I can have my little meal. As I tell you, I do not long to have many things, because I have never had it. I have always been humble and all I want is to be well, nothing more. Being safe, then feeling safe. Security is what I want, peace of mind. It’s the only thing.

But Lula and others seek asylum while many American voters clamor for reinforcing the border, and public discourse ignores the gender-based violence that led to their migration. Perhaps the latter point is not surprising: Gender-based violence is historically understood as a family or interpersonal issue, a framing that feminist scholars argue renders the state reluctant to intervene. Feminist scholar Gillian Youngs writes, “Patriarchal systems have traditionally classified violence against women as private, denoting its distance, and to some degree protection, from the legal gaze and thereby from accountability and punishment.” Thus, women asylum seekers experience unique legal violence: Popular discourse characterizes asylum seekers as fraudulent or as illegal by virtue of unauthorized border crossings. Their lived realities entail holding down jobs, paying lawyers, and raising children while struggling through the aftermath of trauma unacknowledged by the wider society. Structurally, they must negotiate a byzantine legal system that holds out limited hope for a successful case. Away from the public eye, in law offices and closed courtrooms, they fight for permanent legal status.

These women carry the weight of multiple traumatic experiences that cause depression, fear, nightmares, and intrusive memories—symptoms associated with PTSD. Public discourse characterizes them as suspect as political leaders curry favor by conflating them with “illegal immigrants,” thus stigmatizing them as unworthy for inclusion. At the border, they are handled as criminals: held in jail cells and fingerprinted even though asking for asylum is legal. Thus, we call this space compounded marginalization to capture the legal right to seek asylum while delineating the precarity caused by social exclusion, the possibility of forced removal if they lose their case, and trauma that remains unacknowledged by the wider society.

Although the United States enshrines the right to seek asylum in law, apprehensions and incarceration of asylum seekers, coupled with political narratives about the need to “secure the border,” arguably ascribe to women who are fleeing unspeakable violence a status as lawbreakers. Routine arrests and detention of asylum seekers thus culminate in legal violence against this population, processes that cause immediate harm in the form of detainment and punishment, but also threaten long-term outcomes by stigmatizing them as unacceptable for social inclusion. The arrest and detention of asylum seekers constitute a key element in the framework of compounded marginalization: Through processes such as fingerprinting, interrogation, and detention, immigration officials and policies attribute a quasi-criminal status to these women in the eyes of the broader society.

When women cross the border and ask for asylum, they enter what Nicholas DeGenova and Nathalie Peutz call “the Deportation Regime,” in which all who cross the border from Mexico—regardless of the reasons for doing so—are characterized as illegal. Efforts to prevent asylum seekers from reaching the border aggregate them in public perception, and sometimes via policy, with other unauthorized migrants. Thus, at the border, two competing policy imperatives collide: the U.S. insistence on arresting and detaining asylum seekers who cross the border from Mexico, and providing humanitarian assistance and welcoming those fleeing persecution.

Furthermore, some legal scholars note that Western nations built asylum and refugee law on the understanding that state actors perpetrate violence in the public sphere; it did not originate to provide protection to those harmed by non-state actors in the so-called private spheres of domestic partnerships and/or gang violence. Gender-based crimes and persecution, such as rape, have been deemed “private” or “cultural,” and not political, and thus do not easily fit within asylum laws. Such ostensibly gender-neutral protections for asylum seekers fail to acknowledge women’s experiences, although feminist legal advocacy and new precedents are incrementally reshaping asylum law and slowly improving odds for survivors of gender-based violence. Meghana Nayak notes in Who Is Worthy of Protection? the tenuous nature of gender-based claims: “Due to the politics of immigration restriction and the ‘missing’ category of gender, asylum/immigration officials and judges put an added burden on asylum seekers with gender-related claims to prove that they are deserving of legal protection.”

Decarceral thinkers and doers

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

The accretion of policies, coupled with the legal constraints of the U.S. immigration system, complicates the struggle for asylum. A lack of congressional action has meant that the executive branch exerts a disproportionate ability to shape asylum law, a key consideration given how a president’s failure to acknowledge harms suffered by Mexican and Central American women can create legal barriers. Rulings from the nation’s highest immigration court may not be precedent-setting and are often applied inconsistently or arbitrarily. Denial rates vary greatly by court location and individual judges, leading some scholars to label the asylum process “refugee roulette.” In one courthouse where we observed hearings, a judge denied all but 4.6 percent of asylum cases, while another granted it to 71.2 percent. While data separating asylum claims based on categories such as domestic/gang violence or political opinion are not available, statistics on grant rates speak to women’s precarity.

Numerous barriers impede women’s struggle for asylum, and few avenues exist through other means. According to the United Nations, 110 million people were suffering forced displacement as of the end of June 2023, and only a tiny percentage of the world’s refugees receive the opportunity to resettle in another country. The process for obtaining refugee status poses barriers everywhere, and the United States rarely grants it to Central Americans and Mexicans. From 2012 to 2021, 3,085 refugees from El Salvador, 530 from Guatemala, and 494 from Honduras were admitted to the United States; no refugees from Mexico had been admitted. This issue isn’t unique to the United States. As noted by David Scott FitzGerald in his description of Syrian drowning deaths near Greece, deaths could have been averted if more countries allowed people to apply for refugee status at their embassies. “There are very few ‘humanitarian corridors’ providing a legal way for refugees to travel to a safe country and ask for asylum.”

In theory, Central American and Mexican women could attempt to immigrate for reasons unrelated to violence, but legal channels are few, and gendered realities persist: Women typically use the family-based immigration system by relying on male sponsors. Central American women rarely immigrate through the employment-based immigration system; current law gives preference to high levels of formal education and specialized work experience, making receipt of work visas virtually impossible for the very low-income labor and educational attainment that shaped life for many women seeking asylum. With minimal options for winning admission as a refugee or through another channel, and global corridors constricted by unprecedented numbers of people seeking refuge, asylum becomes the lone option for sanctuary from gender- and gang-based violence.

Asylum applications fall into one of two categories: affirmative or defensive. Affirmative asylum is available for people who are not in deportation proceedings. Although an undocumented migrant can apply, most applicants have temporary status, such as a visitor or student visa. In affirmative cases, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) asylum officers evaluate applications and conduct interviews. Interviews are meant to be non-adversarial, with the government not represented by a lawyer. Applicants have no right to appointed legal counsel and must bring their own interpreter. Historically, applicants in the affirmative process are more likely to succeed than defensive applications. As noted by communications scholar Sarah Bishop, there is a “great class bias” in the asylum system, as someone who can afford a plane ticket and a visa can seek affirmative asylum.

Women fleeing gender-based violence often fall on the wrong side of that divide. The Border Patrol will apprehend them shortly after crossing the border from Mexico, and they become subject to removal. Thus begins the tenuous existence for women seeking asylum, as they face apprehension and the need to defend themselves in defensive asylum proceedings—a process that takes years. While detained, asylum seekers are supposed to be referred to an asylum officer for a credible fear interview to determine whether there exists a “significant possibility” of establishing eligibility for asylum because of persecution. Women who establish a credible fear will face a hearing before an immigration judge.

At least, that is how the system is supposed to work. We spoke to immigration attorneys who told us that their clients never had credible fear interviews at the border. Rather, the Border Patrol detained the women before government officials released them and ordered them to appear in immigration court. In other cases, women are deported without having the opportunity to ask for asylum and receive a credible fear hearing, seemingly in violation of U.S. and international law.

Even for those who establish a credible fear, the asylum process is arduous. Women detail trauma—death threats to themselves and family members, assaults, menacing with weapons, multiple rapes—on the witness stand to convince judges that they meet strict legal criteria. But, as noted earlier, asylum laws were not created for survivors of gender-based violence but for victims of political persecution. Western nations built refugee and asylum laws on the understanding that state actors perpetrate persecution in the public sphere—a distinction that leaves those harmed by non-state actors in the private sphere with fluctuating legal guidance.

By treating gender-specific crimes and persecution, such as rape, as “private” or “cultural” but not political, the U.S. asylum system fails to fully acknowledge the gendered realities of persecution by non-state actors—a fact that characterizes the space of compounded marginalization. Without new laws or clear guidance opening the door for more approvals of gender-based asylum claims, women from Central America and Mexico who flee violence face more legal challenges in court.

The asylum system as a whole could be characterized as volatile, subject to shifting standards according to legal precedent and the imperatives of the Oval Office. Bishop writes:

Asylum practice changes frequently and without public warning, and complex, intersecting variables mean even applicants arriving around the same time from the same nation can experience different outcomes. Factors including the kind of persecution an applicant faced, where they entered the United States, the personal whims of the Border Patrol agents they encountered and the political landscape at the time of their entry will impact what comes next.

Even women with extremely sympathetic and well-documented cases face difficulty navigating the asylum system. Through legal battles and advocacy, some survivors of gender-based injury have won asylum and made the case that their gender is an immutable characteristic that renders them a member of a particular social group, but they are not a majority. Congress has been unable or unwilling to pass new laws that recognize the shortcomings of this country’s decades-old asylum laws and create new legislation meeting this century’s concerns. Instead, women are subject to the choices of individual immigration judges, changing interpretations of the law, and decisions made by politicians more focused on appealing to their constituencies and winning elections rather than humane and effective policymaking. Critically, as noted by FitzGerald, asylum globally exists not to protect large numbers of people from the Global South who need protection in Western nations. Instead, the asylum system seeks to sort a limited population that must run a legal gauntlet—if they can cross the border or survive a perilous marine crossing—to prove they are worthy of protection.

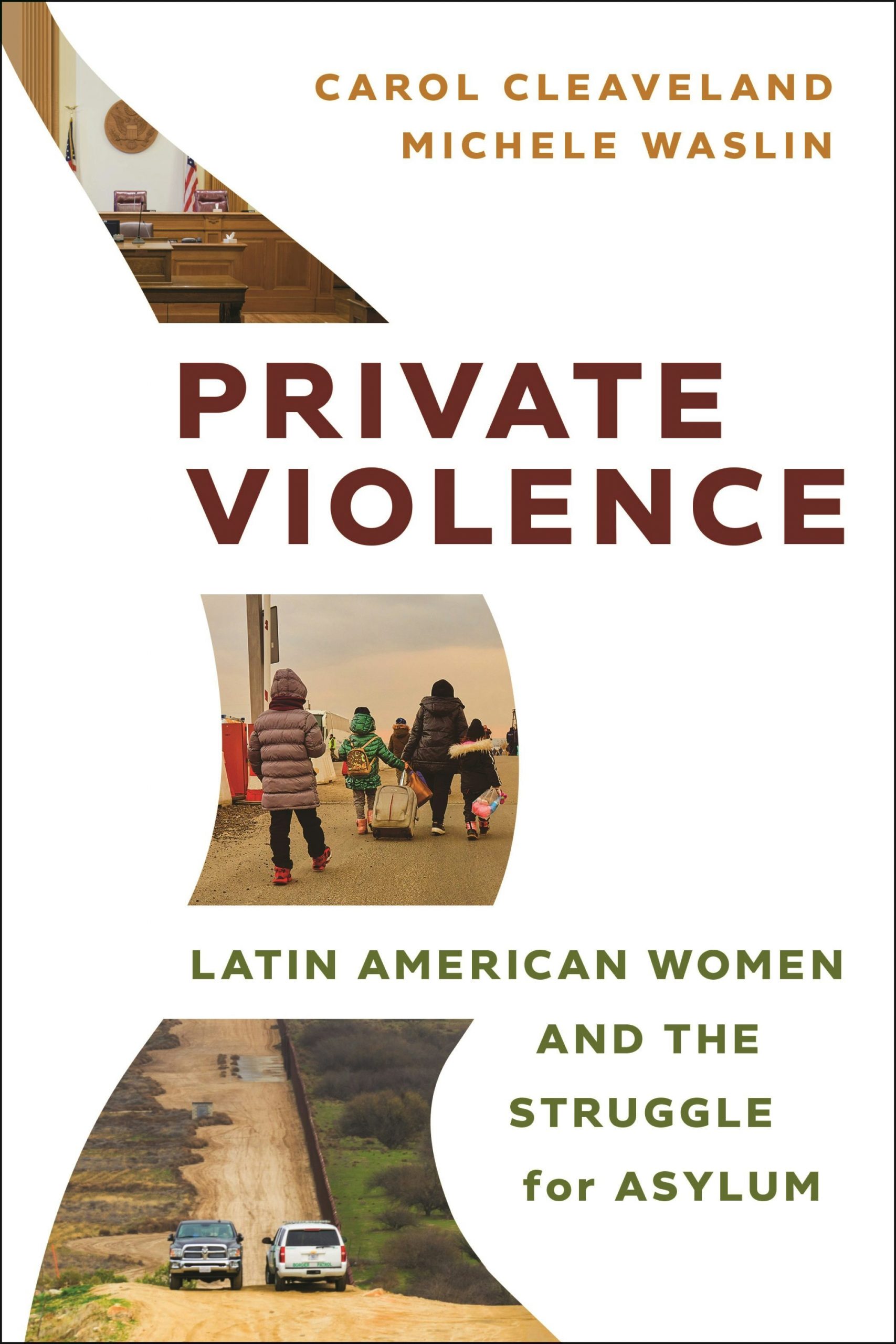

Excerpted from Private Violence: Latin American Women and the Struggle for Asylum by Carol Cleaveland and Michele Waslin, reprinted with permission from NYU Press.

Image: Nils Huenerfuerst/Unsplash