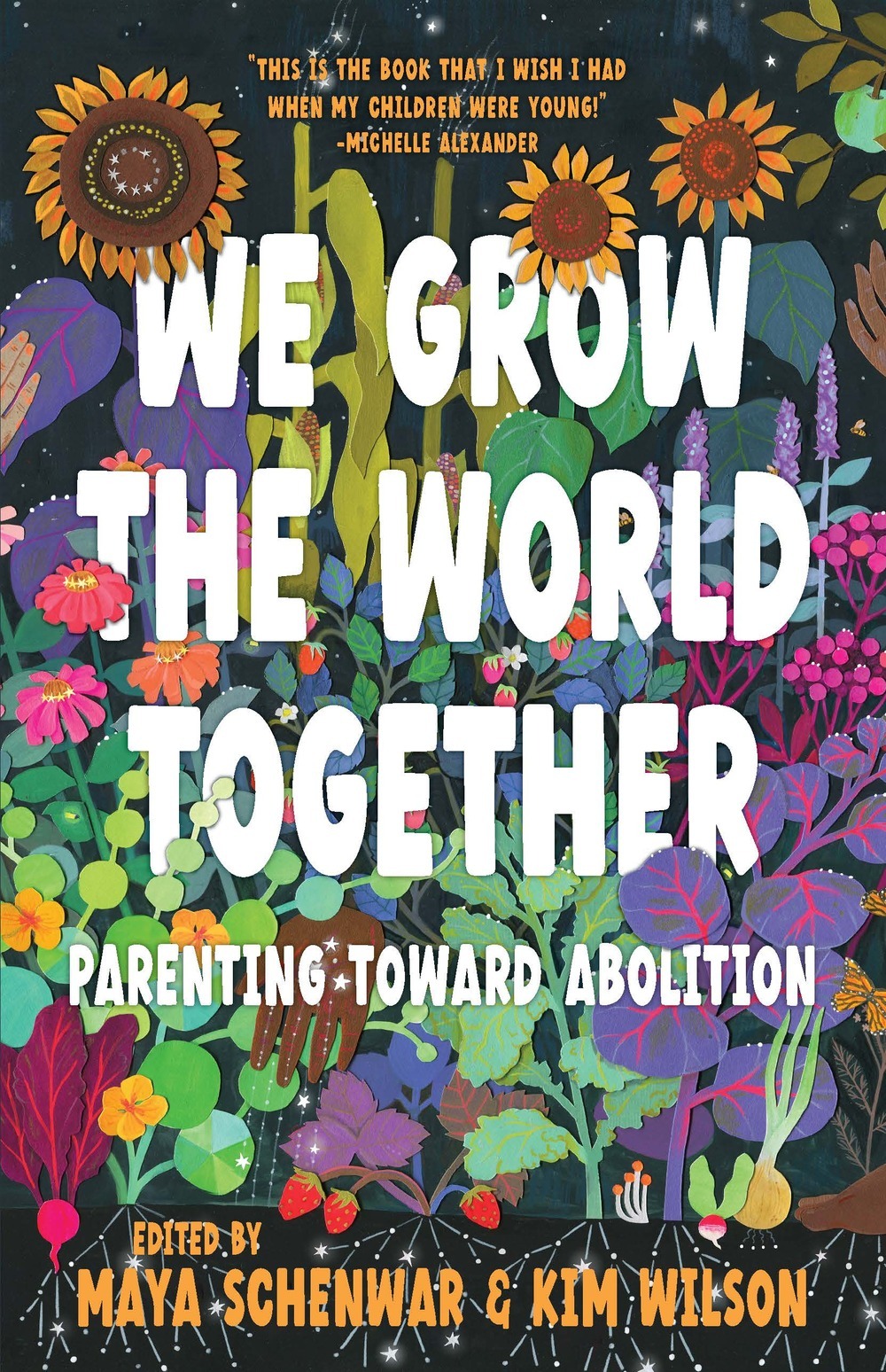

In their new anthology We Grow the World Together: Parenting Toward Abolition, Maya Schenwar and Kim Wilson assemble a group of contributors who engage with hard questions about how the work of raising children intersects with the world-building work of imagining a world without police and prisons. As they note in the following interview, parents are often the most receptive audience for police messaging. How then, they ask, can parents reject fear and instead raise children in a way that centers the desire for a world in which everyone is free?

The following interview with longtime liberation activist Bill Ayers was produced in partnership with his podcast Under the Tree. The full conversation can be heard there as Episode #111.

The interview was conducted before Donald Trump won the presidential election, but the necessity of care as a central component of movement work is made all the more clear in this heavy moment. There is cause for hope in the way caregivers work every day to build the world we hope to live in, even in the most dire of political circumstances.

Bill Ayers: I’m interested in both the title and the concept of your book. What is “parenting toward abolition”? Where did that come from? Abolition is a capacious concept, and one that allows for a lot of different ways of thinking, but I’m curious how parenting in particular came to you two as a topic.

Maya Schenwar: It was a winding road. When I was pregnant with my kid a few years ago, I was involved in abolitionist organizing. Another organizer, after finding out I was pregnant, asked me, “So are you still going to be doing abolitionist stuff once you have your kid?” That stayed with me way before the idea arose for this book. So many people have this idea that not only is parenting separate from organizing and abolitionist work, but also that it’s this anti-radical force. Not simply that being a parent keeps people from being involved in the struggle, but that it conservatizes people—as if you become a parent and are suddenly like, “I like the cops,” you know? But I felt like some of the most abolitionist work that I had done in my life was helping to care for my baby niece while my sister was incarcerated. That felt like applied abolitionist work to me. Yet there wasn’t a broader recognition within the movement that that is part of the work.

The specific idea for this book emerged after the 2020 uprisings, when we were seeing more and more people gravitating toward abolition. Of course, that shift was thanks to decades of grassroots organizing primarily led by Black feminist organizers and queer organizers. But in that moment, this broader consciousness around abolition was a massive—and very welcome—development.

I was a parent of a young child at the time, and I started talking with other parents in the movement. And a lot of people were asking: “What is the place of abolition in relation to parenting and caring for children? Why is that not a central part of these conversations around abolition?” We knew this conversation was necessary. We knew that these punitive state systems were constantly targeting parents, particularly parents of color, and we knew that police-like techniques of social control do sometimes manifest in the home. And we also know that parents are constantly working to build the world we want to see—imperfectly and full of “failure,” as many of our authors talk about, but trying always to “fail better.” There wasn’t much writing on this topic at that point, and I wanted to do something about it.

At the same time, I had major imposter syndrome and a clear understanding of the reality that no parent is an expert. I did not have a massive amount of experience with parenting and had only engaged in a tiny little slice of abolitionist work. I did not want to presume to talk in these really broad terms—and I wanted a coeditor. I was desperately hoping that Kim would say yes, as someone I have deeply admired for many years as a scholar, an abolitionist organizer, and as a mother. I’m so lucky that she did.

Kim Wilson: Thank you, Maya. I’m always really humbled when I hear Maya talk about why she approached me with this idea and deeply grateful that she did. It was one of those things that, for me, I felt had always been integrated into the work I was doing, even if I had not articulated it in that way. But it was how I was showing up for my own kids. I have three children, and both of my sons, unfortunately, are currently sentenced to life in prison. I was doing abolitionist work before they were incarcerated, too, so the idea of bringing a book together with all of these amazing contributors was an absolute dream. It was a very easy and simple yes, absolutely, of course.

With the title, we went through a lot of different iterations and many conversations. All the gardening metaphors kept coming up and it just seemed to fit. We were like: OK, what are we trying to do? We’re trying to grow a thing, right? And we identify as abolitionists, but we’re not firmly planted in this one little abolitionist space. We’re all aspiring. We’re seeing that horizon and we’re working toward that horizon.

Ayers: Both of you have experienced the harms of the criminal legal system and have been engaged in abolitionist work for quite some time. I think it’s so interesting, Maya, that when you became a parent, and when the movement moved forward, you wanted to think broadly about other aspects of your life that could be thought of as abolitionist. So I’d like to hear—and this is for both of you—what is your conception of abolition? And how has it grown or changed in the process of the last few years?

Schenwar: I’m having a sense of slight dread in needing to sum it up neatly, and I’m also thinking about how to talk about it with humility, as Kim and Dylan Rodriguez identified as a priority on Kim’s show—we can make all these grand statements about what it means to parent in an abolitionist way, but in practice, we’re always fucking up. It’s a continual process of trying, failing, and then failing better, as you and Bernardine put it, Bill.

For example, Jennifer Viets wrote this amazing essay for the book about using restorative justice practices at home, like holding family circles. But guess what? When I tried it with my child, they just asked when they could have dessert. I gave them a talking piece, and they asked, “If I take the talking piece, can I get dessert?” It’s that humbling disconnect between theory and practice. “Failure”—and trying again—are part of the process.

Decarceral thinkers and doers

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

Parenting and working on this book over the past few years have taught me a lot about imagination’s role in abolition. I’d always seen abolition as holding two parts, similar to the Critical Resistance definition: dismantling the carceral system and, at the same time, building generative systems for society that meet our needs and desires for connection, wholeness, and liberation. Thinking about abolition in the home, I’ve learned so much about practical imagination from my child; about dreaming, not just theoretically, of all the worlds we can imagine.

A lot of our contributors also wrote about what they’ve learned from their kids. Harsha Walia wrote about how her child brought home talking circles after learning about them in school. (Of course, she knew about this practice from restorative justice.) Unlike my kid, her kid wanted to do them at home. And Harsha says, you know, this was hard work. But her kid forced her to practice, to actually do the thing.

Other contributors wrote about how their parenting experiences and other people’s parenting experiences inspired them to organize. Dorothy Roberts talks about how parents have organized to abolish the system of family policing because of their own experiences of their kids being taken away. Ruth Wilson Gilmore talks about the formation of Mothers Reclaiming Our Children because of the ways those mothers’ children were criminalized. Holly Krig talks about forming Moms United Against Violence and Incarceration after her own experience of being arrested while she was pregnant. And many of these parents are organizing with other parents: that’s the coalition they’re building.

Wilson: Something that comes up for me again and again is how much abolitionist parenting is aspirational. There’s no definitive guide on how to be an abolitionist parent. What I’ve learned, and what our contributors showed, is that we’re all experimenting with different ways of showing up and being present.

A lot of this work, like Maya said, is about embracing failure, not as something negative but as part of a revolutionary practice. We’re going to try things, and much of it won’t work. When it doesn’t work, we reflect, learn, read, discuss, and figure out new ways to be together. A core part of my parenting has been not giving up, showing up even when it’s hard. This project really reinforced that approach for me.

When your children are incarcerated, when you’re dealing with state violence on multiple levels, you have to negotiate those systems—not only in your life, but with their lives, their friends’ lives, their friends’ friends’ lives. The systems we face are designed to tear us apart, to undermine what it means to be family or community. Staying with it is heartbreaking work. It’s not something that lends itself to photo ops or nice poetry.

I find that this book really demystifies the ways we often romanticize abolition. It shows that we can’t just sit around and talk about this thing and somehow that will make it all OK. We are dealing with the reality of the criminal legal system. It’s not optional. Once you or your loved ones are implicated in that system, you have to confront it. You also have to foster that sense that we can build something different—but until we’ve destroyed these systems, it’s a both/and.

Ayers: When I first got the invitation to contribute to this book, I couldn’t help but laugh. I thought, “Abolitionist parenting? This is going to be a trip.” Initially, it seemed out there to me. But the more I engaged with it, the more I enjoyed it. There’s a growing, exciting canon on abolition, and you’ve gathered an impressive group of voices to contribute to this conversation. I feel honored to be among them. And what strikes me is that the book invites readers not only into the conversation but also into the contradictions you’re addressing, because both parenting and abolitionist organizing are full of contradictions, and it’s valuable if we can identify them.

Let me point out two contradictions you’ve already mentioned, and maybe you can expand on them. First, when you become a parent, you want to say it doesn’t make you more conservative—but, in some ways, it does. For instance, you go to bed earlier than you used to. For my partner and I, with young kids and aging parents living with us, we have to pay attention to routines like mealtime, bedtime, bath time, even bathroom breaks.

The other contradiction is one we all discuss. Danielle Evans captures it well: the beauty of motherhood is that all the choices feel wrong. She says, “Ever since my child was born, I’ve had to struggle with how much am I trying to create a decent world for her to live in, and how much am I making her life decent in an indecent world?” Could you explore those contradictions a bit more?

Wilson: The first thing that comes to mind for me is Dylan Rodriguez’s brilliant essay in the book. He discusses discipline as an essential part of abolitionist parenting practice—or aspirational abolitionist parenting practice, to be more accurate. We often shy away from discipline, associating it with punishment and carceral systems, but Dylan argues that discipline is an important, strategic component in both organizing and parenting. We have to be disciplined about how we show up, what we do, how we have each other’s backs. We have to be brave enough to ask questions of each other and of ourselves when things don’t go according to plan.

Personally, I’ve often had to be disciplined in ways that I would rather not be in order to accomplish certain things. Prisons don’t care about what’s happening in your life; they don’t care if you have chronic pain, or you’ve just had surgery—or anything else going on in your life. You just have to do the thing. For my incarcerated family, it’s a promise: if I say I’m going to show up, then I’m going to show up, even if circumstances aren’t convenient. They know they can bank on that.

We all live in this capitalist hellscape. We have to contend with so many things: we have to go to work and get up when we don’t want to and deal with all of these systems and contradictions that run against our politics. That’s where the collective is really important. I can call on Maya, for example, at times when I’m struggling to align my actions with my values. It’s really difficult to live your politics all of the time. You’re forced to make choices under these oppressive systems that you would otherwise not make.

This work starts with creating microcosms where we can act differently, communicate differently, and be joyful—even if when we walk outside, we’re probably going to have to do some things differently. This can be confusing, especially for kids. But you can engage them in those conversations and say, “OK, this is the reason why we have to move this way.”

Schenwar: As Kim has been talking, I’ve been reflecting on the contradiction you raised of this conservatism, or at least limitation, that necessarily happens when you become a parent. You’re right: You can’t stay up all night. You can’t join every protest. You can’t take every risk. But I also think about how those changes can open up new opportunities to talk about these issues with different people, including people who would not be at the protest to begin with.

For example, in the book’s introduction, I talk about going to the playground with my kid, with my “Abolish the Police” shirt or tote bag, and striking up conversations with other parents. If I end up discussing my politics on the playground, the question that usually comes up is: “Well, don’t you want your kid to be safe? How can you be advocating for something like no police?” Of course, as Kim has shared, police interfere with the safety of many of our children. But these moments have raised a lot of interesting conversations for me with parents who have never thought about abolition or asked themselves what safety really means.

I think about my kid’s safety all the time. It’s what keeps me up at night. I don’t want my kid running into the street when there are cars coming. I don’t want someone abusing my kid. But what actually creates safety? Parents are one of the primary audiences for police propaganda because we’re so scared about something happening to our children. We have to get each other to dig deeper and think what safety actually is and what could create it. I’ve had good conversations on the playground about creative interventions that don’t involve policing.

Usually I say the wrong thing and people roll their eyes at me—but I had this one moment on the playground talking to another mom who’d asked me some of these questions. I said: “Well, why don’t we look at the way our kids are solving problems on the playground right now?” They are getting into conflicts, but are they calling the police on each other? No, they’re experimenting. They’re trying different solutions to work through their shit. Some of them are terrible solutions. Some of them involve throwing sticks at each other or calling each other names. But some are actually creative solutions. We see our kids invent a new chapter in their game to work together against the monster in the castle, so neither of them has to be the bad guy. Or they realize they don’t have to fight over who gets the giant stick, that they can take turns. These examples are being offered to us by our children that help us get outside some of the contradictions.

Ayers: There’s something beautiful about being drawn outside of our abolitionist circles into spaces where people don’t already think the way we do.

Schenwar: One of the most challenging experiences I’ve had in organizing over the past few years was when one of the children at my kid’s elementary school last year was tragically killed in a domestic violence incident. In response, a number of parents wanted to pursue a law that they thought would prevent similar tragedies from happening in the future. But a law could mean more criminalization.

A few of us in the parent community who are part of abolitionist organizing got together and started reaching out to folks who are doing anti-violence work around the city, getting their thoughts on how to redirect this energy. One of the main things these anti-violence organizers emphasized to us was, tragically, this child is already gone. No amount of intense supervision or incarceration is going to bring them back. So how do we look at the conditions that made this extreme act of violence possible? What happened and how can we change those conditions?

They brought these questions to the parent community, which included people who are not abolitionists, but when it was put in the context of this particular situation, they got it. We started brainstorming together, and one of the things that came up was the lack of education around gender-based violence and the dynamics of patriarchy in schools. So some of the parents talked to Healing to Action, which is an amazing organization that mobilizes survivors of gender-based violence to become organizing leaders, and they shared about their efforts to push for a comprehensive sex-ed curriculum in Chicago public schools that includes education around gender-based violence. Now more parents had the opportunity to support those efforts. I thought that was beautiful.

Bill Ayers: That’s a great example of elevating the conversation about what really creates safety. Parents are often the primary audience for police propaganda because we’re so afraid for our children, but conversations like that show how we can move toward community action.

Image: Jonathan Borba/Unsplash/Inquest