Once the facts can be clearly established and shown to the people, where these dogs are practicing slavery under the color of law, then this automatically requires a special investigation by the people to look for themselves. They will find that these judges are criminals.

—Ruchell Magee

Angela Davis’s former codefendant Ruchell Cinqué Magee is familiar to some but not to the general public. In the absence of a book or memoir to attract attention to his story, Magee’s “autobiography” is written in the docket for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, in the case Ruchell Magee v. Daniel E. Cueva. His March 2022 petition against the warden of the California Medical Facility, Vacaville, where he is held describes the biases and violations of the courts and the refusal of courts to review his case without bias. Magee’s unpolished narratives maintain that the U.S. legal system ensnared him, along with other poor and Black people, into slavery, and thus he has a right to free himself from unjust captivity.

Incarcerated for more than sixty years, politicized in prison, Magee self-identifies as a political prisoner railroaded by law into captivity. Abolitionists assert that California’s extensive prison system is built upon the persecution of poor Black, Brown, and Indigenous peoples facing indeterminate sentences for petty theft and drug-related crimes. For his part, Magee was never convicted of aggravated kidnapping in a fair trial, nor was he convicted of murder—though, even if he had been, most state sentences for murder permit parole after fourteen years. And so, under a predatory economy of violence, one that is often racially fashioned, Magee and other imprisoned politicized rebels call themselves “slaves.”

While incarcerated, Magee took the name of “Cinqué” from the enslaved African Sengbe Pieh who led the 1839 rebellion to commandeer the slave ship La Amistad, and who, with former U.S. president John Quincy Adams as his attorney, convinced the Supreme Court that Africans have the right to resist “unlawful” slavery.

This essay draws attention to Magee’s lifelong struggle against the carceral state, his analysis of its functioning, his strategies for abolition, and his unique understanding of the entanglement of the categories “slave” and “citizen” within a democracy deformed by its historical and contemporary expansive carceral system. Magee is now eighty-four. Eligible for parole since 1981, and denied more than a dozen times, there has never been a more urgent need to honor his insight and bring attention to his plight and abolitionist agency.

Born in Ku Klux Klan country in “Frankkkington,” Louisiana, Ruchell Magee, at age sixteen, was charged in Louisiana with an “attempted aggravated rape” for having a relationship with an older, married white woman. That was in August 1955, the same month and year that fourteen-year-old Emmett Till was tortured and lynched for allegedly whistling at a white woman, Carol Bryant, who died last week at age eighty-eight. (Till’s murderers, acquitted by an all-white jury, later confessed to the crime in a paid Look magazine interview.)

Magee became the youngest person sent to Angola prison, a former slave plantation. Sentenced to twelve years of hard labor, he was paroled after eight. According to the Jericho Movement, the Louisiana court confiscated his inherited property and mandated that he leave Louisiana for parole in Los Angeles in 1963.

Six months later, Magee and his cousin got into a dispute in a nightclub with Ben Brown, a pot distributor, over a $10 bag of marijuana. Brown called the police, telling them that Magee had tried to kidnap him. During the arrest, LAPD beat Magee so savagely that he was hospitalized for three days. Magee had witnesses who could testify that the altercation over pot included no kidnapping, but the Superior Court of Los Angeles County convicted him of aggravated kidnapping. He was sentenced to an indeterminate sentence (seven years to life, similar to the one-year-to-life sentence meted out to eighteen-year-old George Jackson). In 1964 an appeals court reversed Magee’s conviction. In 1965 it was reinstated by a judge who refused to let Magee fire incompetent counsel and allowed guards to beat and gag Magee before the jurors when he vociferously protested (somewhat similar to the violence Judge Julius Hoffman permitted against Black Panther Bobby Seale in 1968 during the Chicago Eight trial; after Seale was removed it became the Chicago Seven trial). As had other impoverished, Black defendants, Magee v. Cueva notes that Magee in the 1965 retrial had been forced into an insanity plea without psychiatric testimony/documents by the judge, only to have the plea withdrawn after the jury convicted him of the 1963 aggravated kidnapping charges.

While in prison, Magee developed legal skills and assisted other prisoners with court cases, emerging as a thorn in the side of the prison bureaucracy. In February 1970—as Magee finally, after seven years, neared parole eligibility—San Quentin prison guards tear-gassed and beat Black prisoner Fred Billingsley to death in his cell. Magee would file a wrongful death lawsuit to help the Billingsley family obtain a substantial financial settlement. The guards who killed Billingsley were never charged with homicide.

On August 7, 1970, Magee as well as William Christmas were in the Marin County Courthouse testifying as defense witnesses for John McClain, who was facing charges for assaulting a guard at Soledad Prison in retaliation for Billingsley’s murder. All three men were in Soledad Prison, as was prison theorist and militarist George Jackson, the older brother of seventeen-year-old Jonathan Jackson.

Jonathan, reportedly one of Angela Davis’s bodyguards, had possession of guns registered in her name. At that time, Davis was a key spokesperson for the Soledad Brother Defense Committee (SBDC). SBDC sought to exonerate George Jackson, Fleeta Drumgo, and John Clutchette, who were charged with the killing of a white guard, John Vincent Mills, at the Soledad State Prison after another white guard, Opie G. Miller, had shot and killed W. L. Nolen, Cleveland Edwards, and Alvin Miller. (Jackson was killed by prison guards in San Quentin in 1971; Drumgo and Cluchette were acquitted in 1972.)

On that day in August, Jonathan raided the Marin County Courthouse in an attempt to engineer a hostage swap for the Soledad Brothers, with the additional aim of taking Magee to a radio news station where he could expose on air the racism of California prisons and courts. When Jon Jackson walked into the courtroom, announcing that he was in charge, the three incarcerated men spontaneously took the weapons he offered them; there was no conspiracy. Assuming that middle-class white lives were valued by the state more than their own, the Black men took as hostage three white women jurors and two white men—Judge Harold Haley and Assistant District Attorney Gary Thomas—and escaped to a van in the parking lot.

Rather than shooting out the tires and waiting for negotiators, prison guards fired into the van. The Coalition to Free Ruchell Magee asserts that, during the shooting, Magee used his body to shield the women jurors in the van. While the jurors were saved, the guards killed three of the Black rebels and the white judge, permanently paralyzed the ADA, and shot Magee multiple times. (A similar tragedy would happen in Attica in 1971 when the National Guard killed white hostages to neutralize “slave” rebels.)

During their trial as codefendants in 1971, Magee and Davis served as their own counsel. Davis, though, was assisted by six private attorneys trained at prestigious law schools. She and her attorneys soon agreed to sever the cases. Davis would then be able to receive bail and work more closely with her attorneys and Communist Party USA defense committee. This also allowed her to distance herself from Magee’s defense strategy, which was to assert his right as a slave to rebel for freedom. Davis, as a citizen, maintained that she never gave Jon Jackson permission to use her weapons in a rebellion or raid. In June 1972, an all-white jury acquitted Davis of all charges. The trial judge then entered the verdict into court records; the judge’s routine action may not seem to require noting, but the significance will become clear soon.

During his 1973 trial in San Francisco, Magee’s attorneys, Robert D. Carrow and former U.S. attorney general Ramsey Clark (unlicensed in California, Clark offered free legal services), argued in People v. Ruchell Magee that Magee had a legal right to rebellion. The Coalition to Free Ruchell Magee asserts that a Black juror held out for acquittal, arguing that the 1963 aggravated kidnapping conviction over a marijuana dispute was unjust because of lack of evidence, and thus Magee had the right to rebel against his imprisonment. Likewise, Magee argued in court that, as a slave, he had the right to free himself from unjust captivity. His spontaneous acceptance of weapons was a taking up of arms to free himself from repression.

The jury largely agreed. The New York Times reported that the jury issued a 12–0 acquittal for murder and a 11–1 acquittal for aggravated kidnapping. The jury reasoned that prison guards had shot and killed Judge Haley; and that Magee took hostages not for ransom but in order to negotiate an interview on a radio news station and share with the public his experiences with corrupt judges and a violent prison system. The jury did convict Magee of “simple kidnapping,” which carried a one-to-five-year sentence, with possibility of parole in one year.

However, following the verdict, the presiding judge did not read or enter the jury verdict into the court records. With the judge failing to enter the jury’s verdicts, Magee was caught in a Kafkaesque judicial circuit.

In August 1974, Magee pled guilty to aggravated kidnapping but retracted his guilty plea on the same day. Yet the judge upheld that plea—and the life sentence that came with it. The New York Times asserts that Magee was “so frustrated” with the legal proceedings that he pled guilty in order “to get it all over with.”

News media contributed distortions that upheld the courts as valid. For example, the New York Times coverage of Magee’s trial refers to a “shoot out” at the Marin County Courthouse, but historians (e.g., Bettina Aptheker) have noted that prison guards were the only ones to fire their weapons. The New York Times also described Magee as someone who “often shouted and argued vehemently in court” but who was expressionless and voiceless when Superior Court judge William Ingram pronounced the life sentence. Depression is a strong possibility for defendants, given the machinations of the courts and a living death sentence in prison. However, Magee in later interviews states that entering a guilty plea was a legal strategy on his part to bring attention to corrupt courts that had not acknowledged his 1973 acquittals of the most serious charges. While small numbers of determined demonstrators continued to protest outside the courts on Magee’s behalf, the final guilty verdict was entered in January 1975.

Magee, though, continued his work as a political strategist seeking abolition. For example, in 1975, organizing for the National Defense of Political Prisoners and the Panther 21 case, human rights activist Yuri Kochiyama sent Black Panther Party/Black Liberation Army member Jalil Muntaqim a draft petition on U.S. political prisoners—perhaps the first of its kind—for presentation to the United Nations. Muntaqim passed the petition to the next cell, occupied by Magee; the jail house lawyer added legal citations and references, and then sent the petition “upstairs” for final review by BPP/BLA leader Geronimo Pratt. (Magee and Pratt were on trial in California at the same time as Davis but most media ignored their trials, failing to investigate and show to the public how Magee was railroaded and Pratt was framed by the FBI and LAPD.)

In 2021 the Coalition to Free Ruchell Magee, organizing for Magee’s parole, had to no avail attempted to highlight how the deadly impact of the COVID-19 pandemic within prisons was especially dangerous for the elderly Magee. In 2022 Black Power Media cofounder Jared Ball devoted part of an episode of his show I Mix What I Like to the Coalition to Free Ruchell Magee and asked about Magee’s active supporters. The coalition promised to reach out to Angela Davis and others to increase advocacy. Following that podcast, they developed the March 19, 2022, Free Ruchell Magee 83rd Birthday Virtual Rally, a live-streamed event. Its first three speakers were Muntaqim, Davis, and Jonathan Jackson, Jr.

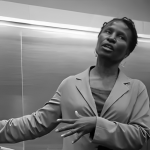

Describing Magee’s incarceration as “the most egregious example of carceral injustice of our time,” Davis offered her support: “I want to say ‘Happy Birthday’ to my brother, but I cannot in good conscience wish you a happy birthday without recommitting . . . to the struggle to free you, my brother Ruchell. It is an abomination that Ruchell is behind bars.” Davis noted that San Quentin guards had killed McClain, Christmas, and Jonathan Jackson—and more: “And let us not forget that the guards were responsible for the death of Judge Harold Haley.” She spoke of Magee as “the first person to link the prison system to slavery.” Maintaining that half a century ago most people could not “grasp . . . the genealogical system” of enslavement, Davis highlighted Magee’s analyses that corrected our “failure to address that we were living the afterlife of slavery.” Reading abolition scholarship, according to Davis, leads her to think of Magee. For Davis, Magee, as the longest-held political prisoner, must “be freed by the movement as a testament to the righteousness of our struggle for better and more just worlds for everyone.”

Seven months after Magee’s birthday event, PBS posted a video called “How an FBI Poster Became a Black Power Symbol,” in which Davis and other academics discussed the FBI wanted poster for Davis’s arrest after the Marin County Courthouse tragedies. The video garnered over 400,000 views, compared to the roughly 400 views for the Magee birthday virtual event. The PBS video opens with images of harried white prison guards (one photo prominently features a Black guard aiming at the van with hostages) and the visual menace of Black imprisoned men and a teen in resistance wielding guns. The video does not mention the names of those who died or who shot them—prison guards. It also fails to name Magee and to recognize that Davis’s former codefendant is still incarcerated. Also disappeared is the fact that the FBI’s COINTELPRO program, along with local police and prison guards, targeted Black Panthers and prison rebels—not Davis. (Her flight from California when police sought to interview her about the use of her weapons prompted the FBI pursuit; ten weeks later, Davis and her companion were arrested without agents drawing their weapons.)

The popular PBS video centers iconic visuals: the FBI poster, Davis’s captured guns, and her hair styled in an Afro. Its narrative assumes a framework that centers the citizen within democracy’s progress. There is no place for a narrative that is about slavery’s continuation, or the role of slave rebellions as avowed by our modern Cinqué. Thus, popular memory, circulating through liberal and state platforms, engulfs objective history and Black radical agency.

Freedom Archives founder and former political prisoner Claude Marks, an advocate for Magee, asserts that abolition must seriously address anti-colonialism, slavery, and slave rebellions in order to ally with the incarcerated who, while fighting for their lives, support communities that leverage mass movements into “magical moments” enabling the public to better see police and prison corruption and brutality. Magee’s analyses center colonialism: “Slavery 400 years ago, slavery today.” Over 184 years since Amistad, 158 years since the ratification of the Trojan Horse Thirteenth Amendment to allow slavery’s continuation within prisons, politicized prisoners manifest as “slave rebels,” and are targeted as such by the state. Magee insists that he was illegally convicted by a “a slave operation” within the courts. The eighty-four-year-old enslaved senior citizen continues advocating abolition while searching for solidarity: “I’ve wrote to about a thousand lawyers. They don’t respond.”

Editor’s Note: In the four-part series Abolition Alchemy, of which this is part two, Joy James and Kalonji Changa engage in an extended conversation with imprisoned intellectuals and organizers. Changa and James continue this discussion on YouTube with a new video, Living Death: Ruchell, Mumia & Sam, they recorded for Black Power Media to accompany their Inquest article.

The Coalition to Free Ruchell Magee asks the public to sign petitions and write letters to California Governor Gavin Newsom and Los Angeles County District Attorney George Gascón to demand clemency or release due to Magee’s advanced age and fragile health.

After viewing Kalonji Changa and Jacquie Luqman’s dialogue on the Atlanta nonprofit/city council awards that were silent about Cop City violence and political prisoners such as Magee, Julia Wright was inspired to approach Davis, who agreed to testify about Magee at the April 26, 2023, UN Mumia Liaison Group’s hearings for the UN EMLER (Expert Mechanism on Law Enforcement and Anti-Black Racism) on political prisoners. Held at Atlanta’s Auburn Research Center, these hearings focus on the cases of Magee as well as Imam Jamil Al Amin, Ed Poindexter, Kamau Sadiki, Major Tillery, and Mumia Abu-Jamal.

Image: Ali Marwan/Unsplash