In recent years, rates of incarceration among American Indian and Alaskan Native people have been rising faster than for any other racial or ethnic group. “Because we are a colonized people,” Luana Ross (Salish and Kootenai) relates, “the experiences of imprisonment are, unfortunately, exceedingly familiar. Native Americans disappear into Euro-American institutions of confinement at alarming rates.” According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the groups most likely to be killed due to injuries inflicted by law enforcement are Native Americans, followed by African Americans. These statistics tell a story about the deliberate defining of certain kinds of bodies and lives as “criminal” and thus in need of “apprehending” through a myriad of state punishing practices.

The fact that state violence is experienced at radically different rates depending on race, ethnicity, or Indigeneity is nothing new, and has its roots in the origins of the United States as a settler colonial and slave state.

In Why Indigenous Literatures Matter (2018), Daniel Heath Justice (Cherokee) delineates between “stories that wound” and “stories that heal,” the former being the dominant settler colonial narratives told about Native and First Nations peoples. Quite likely any person—Indigenous or not—who has grown up on this continent could, if called upon, regurgitate these stories that wound: brave “explorers” penetrating untouched virgin land; Thanksgiving meals involving happy, patriarchal nuclear families of pilgrims and Natives; young Indigenous heterosexual ciswomen who fall in love with benevolent white cismen; the “progress” of westward expansion bringing Christian sexual norms; “primitive savages” who antagonize settlers with deviant gender identities; “noble savages” who adapt and assimilate to Euro-American ideals. . . . These stories that wound are integral to the carceral state, providing a founding myth for how the United States imagines itself to mete out justice and redress harm, and excuses its own inherent violence.

The U.S. settler state is not discrete from the slave state, however. They are concomitant, parallel phenomena that culminate together in today’s carceral state. Both have been central to the creation of the U.S. state as an Othering and punishing apparatus. On top of these ways of producing difference through racialization and colonization, there are multiple intersections of gender and sexuality that have contributed to the particular kind of Otherness produced by the combined slave/settler/carceral state—and this reality continues to impact the experience of imprisonment in the present day. Saidiya Hartman contextualizes this historically in the colonial and antebellum eras, when the confluence of racialized and gendered Othering became enshrined in law: “The failure to comply with or achieve gender norms would define [B]lack life; and this ‘ungendering’ inevitably marked [B]lack women (and men) as less than human.”

Yet mainstream LGB (and sometimes T) activism has colluded with slave/settler/carceral state interests and focused on legal reform efforts, such as passing hate crime laws. Law scholar Dean Spade identifies the strategy behind this maneuver, noting that being a crime victim grants the legal protection that is often desperately sought by vulnerable populations. But state protection entails competing for safety and security as a subject who conforms to norms of good citizenship and simultaneously distancing oneself from what Amy Brandzel describes as less desirable, abject (non)citizen positions—requirements that Black queer, trans, and gender nonconforming people are always denied under the settler/slave/carceral state. Ultimately, any legislation bolsters punitive, retributive justice systems and, per Brandzel, “serves as an alibi to state violence” within white supremacist, settler colonial, cisheteropatriarchal structures that, in Spade’s words, “cannot be redeemed.”

Gendered settler norms and restrictions are reproduced inside jails and prisons. Not only are these spaces antithetical to any traditional healing practices—in reality, they are actively antagonistic to those aims—they also subject Native individuals who identify as queer, trans, gender nonconforming, and/or Two Spirit to the cisheteropatriarchal whims of non-Native police, corrections officers, wardens, doctors, and counselors.

The methods settler colonialism has used to instill cisheteropatriarchal norms operate at multiple registers, through Indigenous peoples’ forced assimilation into institutions like prisons and residential schools. For Native Americans, historian Ronald Takaki notes that punishing and isolating mechanisms—such as the asylum, the boarding school, the penitentiary, and the reservation—all serve “the principle of separation and seclusion” that “would do more than merely maintain Indians: It would train and reform them.”

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

Part of what colonists sought to “reform” was what they perceived as Indigenous people’s deviant sexuality due to how settlers, in Scott Lauria Morgensen’s words, “interpreted diverse practices of gender and sexuality as signs of a general primitivity among Native peoples.” Deborah Miranda (of the Ohlone-Costanoan Esselen Nation) demonstrates that part of the murderous momentum of settler colonialism has been the deliberate “gendercide” of these Native identities and practices deemed “queer” in terms of gender and/or sexuality.

Other Indigenous feminists also confirm that the settler state actually requires the violence and death of the gendered and sexual Other, because, as Audra Simpson (Kahnawake Mohawk) indicates in the article “The State Is a Man,” an agentic, autonomous, and self-determining Other poses a threat to the settler state’s sense of sovereignty. Sarah Deer (Muscogee Creek) provides a comprehensive overview of U.S. settler colonialism’s sexually violent history, in which there is an inseparable connection between the sovereignty of Native bodies and the sovereignty of tribal nations. “It is impossible,” Deer tells us, “to have a truly self-determining nation when its members have been denied self-determination over their own bodies.” The loss of self-determination on an individual level creates the conditions for a loss of political self-determination, and vice versa.

In place of what Ardele Haefele-Thomas identifies as “the more open gender possibilities” and sexual possibilities that settlers have demonized in Indigenous communities, the settler colonial state sought to impose, in Sarah Hunt’s words, “a binary gender system based on a hierarchy of male supremacy over women that erased non-binary Indigenous gender roles, such as those we now call transgender and Two-Spirit.” By erasing gender and sexual diversity, bodily autonomy, and, ultimately, tribal sovereignty, narratives of “backward” people are formative to the violent, even deadly, punishment of Indigenous peoples under the slave/settler/carceral state.

All of this is to say that stories matter; stories have an impact. If the dominant ones told about Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) communities have wounded and continue to wound—specifically by justifying the deadly punishment doled out by the carceral state—then any attempt to tear down and exist outside and in spite of these conditions must confront these stories. Overall, I see the stories told about Black and Indigenous peoples to be central to the carceral practices that need to be combatted. Conversely, the stories told by Black and Indigenous feminists, queer, trans, gender nonconforming, and/or Two Spirit people help to challenge policing, prisons, and punishment. I am in no way saying that to be Black is the same as to be Indigenous, or vice versa. What I am arguing is that to be either (or both) means that narratives that are not our own are foisted upon us. These narratives have formed parallel justifications and valences of Othering as it pertains specifically to the carceral state. (For instance, Black and Indigenous peoples are both overrepresented in incarcerated populations.) If these stories that wound precipitate parallel effects, then it behooves those of us invested in prison abolition to investigate and counter them and to create our own.

However, the narratives of the slave/settler/carceral state belie the continued existence, resistance, and survival of Black and Indigenous lives that exceed the forces that seek to control, punish, and kill with impunity. We certainly need to tell our stories of lives that have not been entirely determined by and, indeed, have forged sociality in spite of the restrictions of the slave/settler/carceral state. These are what Justice might call stories that heal—alternative visions that speculate beyond the many harmful narrativizations I’ve laid out above.

At the same time, abolition must also counter the stories that wound by denarrativizing the Othering lies that the slave/settler/carceral state requires to define itself in relation to. It is only by exposing and unsettling these narratives as stories that wound, which prop up attempts to dictate lived realities, that we can then see we are living in a past that is not past (to borrow Christina Sharpe’s evocative phrase). We are living with the historical resonances in the present day, and we must do the work of denarrativizing them to resist retelling them.

The contemporary carceral state draws from the foundational narratives of the slave state and the settler state to inform its consensus about who is to be punished, controlled, and killed under (and beyond) the purview of law. These are narratives that must be actively opposed. Black and Indigenous peoples working toward the abolition of the slave/settler/carceral state challenge what we have all been told are the limits of possibility and actively forge paths beyond.

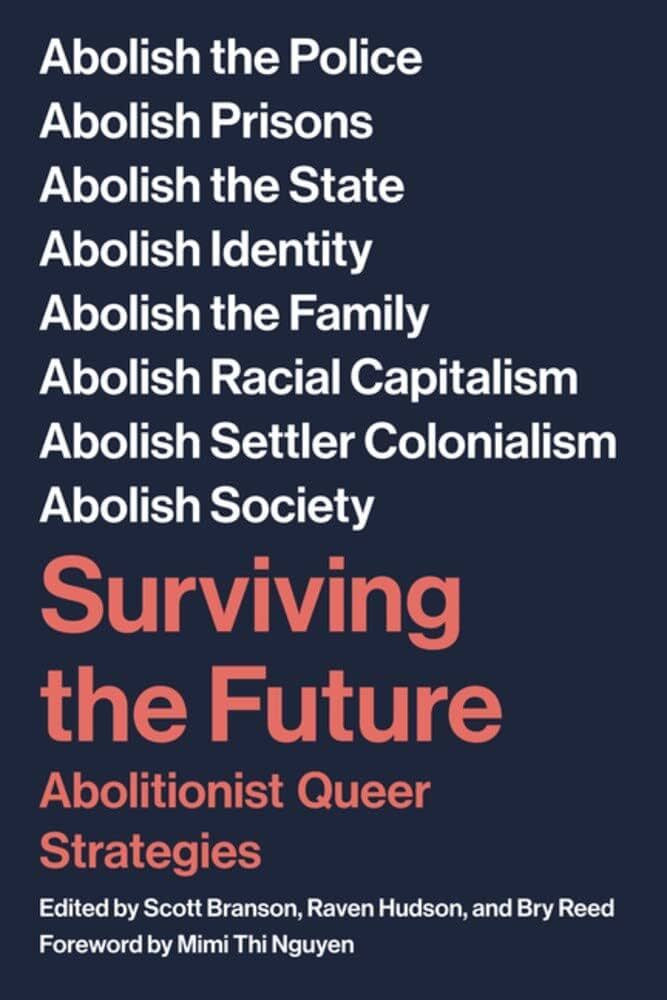

This article was adapted by the author from their essay “Telling ‘Our Stories’: Black and Indigenous Abolitionists (De)Narrativizing the Carceral State” in Surviving the Future: Abolitionist Queer Strategies, edited by Scott Branson, Raven Hudson, and Bry Reed. It appears here with permission from PM Press.

Image: Bailey Littlejohn/Unsplash