It was through prison art activism that I got connected with Duane “DJ” Montney and James “Yaya” Hough. Both men are talented artists who lived through decades of incarceration and make art about their experiences. Fortunately both are now free. I first met DJ through the Prison Poster Project, when he designed an incredible panel relating lynchings during slavery to the death penalty. Yaya and I met some years later, when he reached out to the art collective where I was working and we got to feature one of his pieces in a gallery show. I’ve been working with both of them ever since.

DJ and Yaya have played significant roles in making Creative Resistance and our yearly art shows what they are today, and I got the chance to bring them together to talk about their experiences as incarcerated artists. What follows is an interview, sort of—mostly, it’s a conversation about the power of art in prison between two of my favorite artists and dear friends.

This is the second half of Inquest’s feature about the work of Creative Resistance and Let’s Get Free. To read the first part, about Creative Resistance’s annual shows of work by incarcerated and formerly incarcerated artists, click here.

—etta cetera, cofounder of Creative Resistance and Let’s Get Free

etta cetera: To start, could you guys give a bit of an introduction to yourselves and your art?

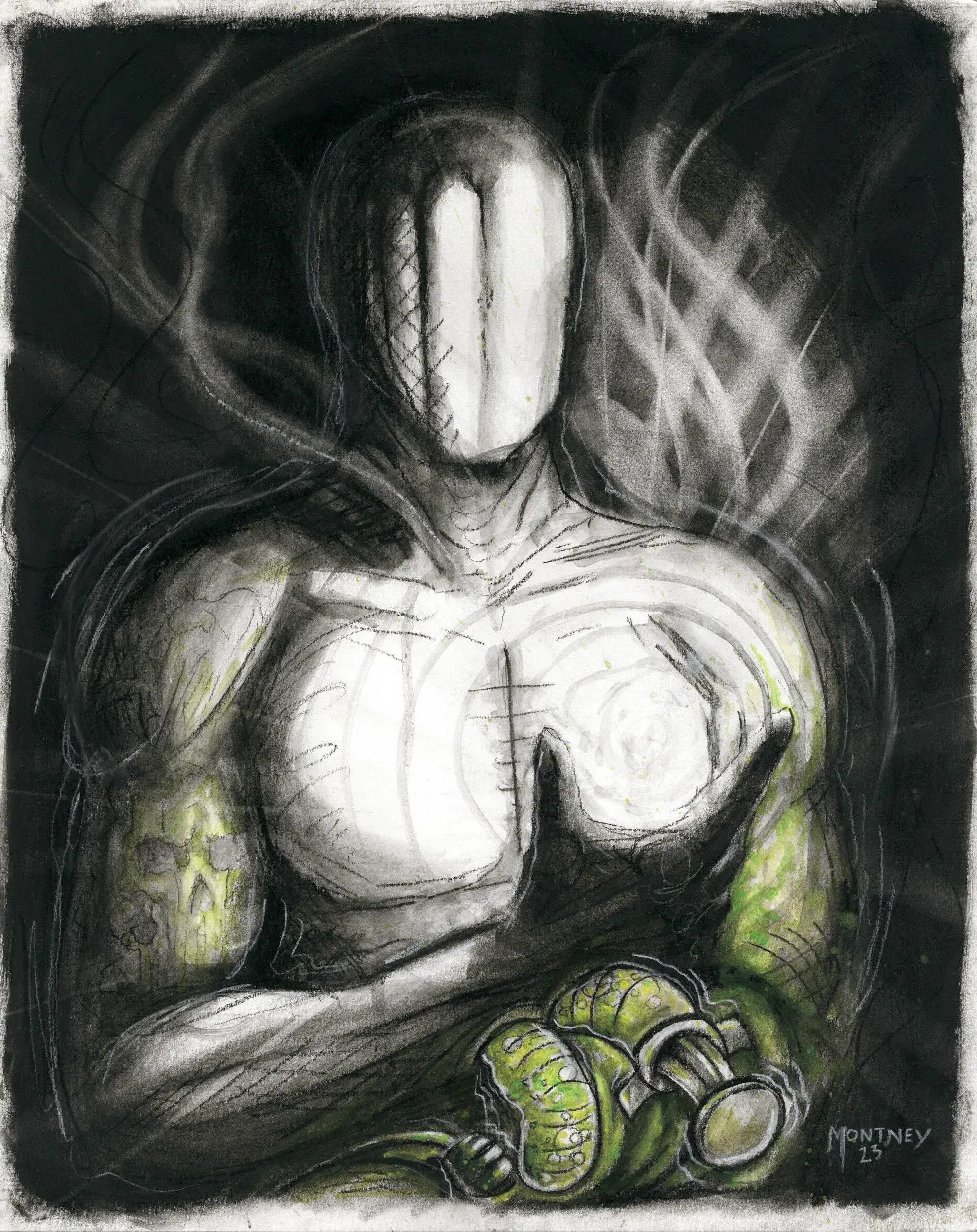

Duane “DJ” Montney: I went to the hole at age twenty and started tattooing, and that’s how I got started as an artist. Later, I transitioned to painting and other visual art forms. I met etta when she saw some of my work at the University of Michigan Prison Creative Arts Project show and asked me to contribute something to the Prison Poster Project. I really liked the idea and the energy behind it. At that time, I was starting to involve my art with talking about political things within prison, and this opportunity really helped me to step my game up. It gave me a more open atmosphere where my work could be raw.

One of the pieces I was involved with was a death penalty scene. Even though my state isn’t a death penalty state, I did time in a death penalty state due to overcrowding. I was sent to Virginia, and the Death House was right in my backyard. I’ve locked eyes with guys who were getting ready to be sent to their death. So I know that crazy feeling when you look in somebody’s face, and know that they aren’t going to be around after Tuesday.

It’s easy to look around the yard sometimes and find the things that either piss you off or make you happy or make somebody think about prison in a different way, whether it’s the normal things that people associate with incarceration, or the funny things that might happen within a prison. I’ve been in dog training programs, so I’ve done paintings of dogs and stuff like that. But I’ve also done pieces dealing with overpriced store goods and horrible food. It’s helped give me a voice to show people a different side of incarceration, the good and the bad.

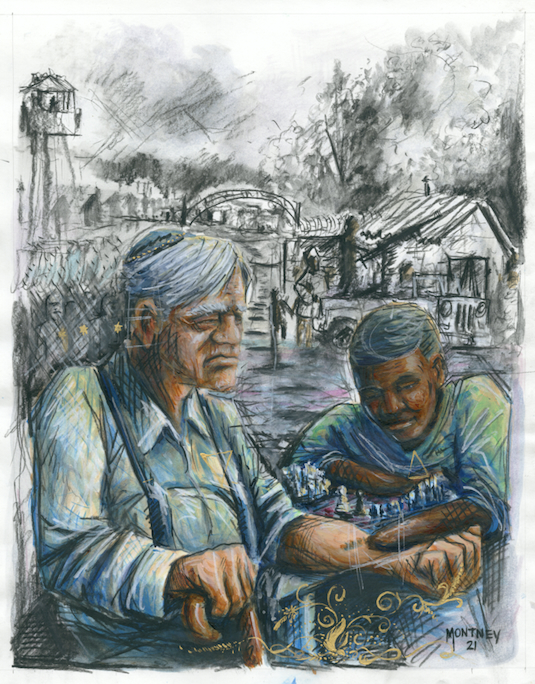

James “Yaya” Hough: I did twenty-seven years incarcerated as a juvenile, was released in 2019, and since then, I’ve had the blessing and the privilege to be a working contemporary artist. Fortunately, I’ve been able to have shows in New York and plenty of other places. With connections through Art for Justice and the Ford Foundation, I was able to execute a piece in Battery Park City in Lower Manhattan called Justice Reflected. I would say that project is the culmination of the period of my release from incarceration to the moment of its inception. That piece is currently being bounced around as possibly being part of the permanent collection of artworks in Battery Park City. It has a very strong connection to a very important place in that park, which is where Frederick Douglass first landed by boat and stepped onto the shore in New York City. That location is just a very short walking distance from where this work is located. It’s a beautiful location.

I want to echo what Duane has said: part of my personal transformation was through my artwork. I’ve always been an artist, and it’s one thing to be an artist, but I think you need life experiences to shape you, which in turn shapes what you create. In many ways, you are the sum total of your experiences and how you filter them through your mind and your emotions. Prison definitely played that role in shaping how I view the world and how I express myself through art.

For a good two decades during my incarceration, I had been working primarily with organizations in the Philadelphia area; the prison I was in was about twenty-five miles out of Philly and had a very strong connection to the city. I was able to do a lot of art-related activism through the prison and the community we built there. But being from Pittsburgh, while I enjoyed working in Philly, I still wanted to have an impact in my hometown in some way. I wanted to begin to lay the groundwork for that. I found out about Boom Concepts—where Let’s Get Free was holding its art shows at the time—and wrote to them. I said, let’s see how I could integrate myself and replicate, in some ways, the same things I was doing in Philadelphia to impact people in Pittsburgh, particularly the incarcerated population, their families, and the prison brothers I was incarcerated with.

Art has always been intrinsic in social justice movements. Pick any movement from around the world. They all have their particular artists, poets, musicians, or collectives that push forward the politics. Art is not just a beautiful, decorative thing but a powerful force. To me, art and education are the two most powerful, transformative tools that exist to spark that redemptive flame within a person. Art and education have an illuminative effect on the mind and the spirit of anyone, but particularly someone who is in dire need of those two forces to redeem themselves; not necessarily to become another person, but to rediscover who they truly are.

I know you can identify with this, DJ. I used to invite everybody to art classes, and so many guys used to say they used to draw as a kid but they stopped. And it’s like, well, why don’t you restart? What if you reclaim that part of who you are and let it spark something within you? I’ve seen that happen with guys who were weightlifters but became casual watercolor painters. We have these concentric spheres of existence within any society, and in prison, you have the same thing. There are guys who are into sports, guys who play ball or lift exclusively, and they’d be over there painting with us at night. Other guys would see them get better, and some of them would actually get to sell or trade a piece. It wouldn’t just enhance their own self-esteem, but it would add something new to their personality, something they could share with their family.

DJ: I’ve seen a lot of people reconnect with their family through art, whether it’s cards for their kids, a portrait of their mom, scenes from their youth. They send those pieces home, and their families just light up. It’s amazing to see. Through the University of Michigan, they have an art show where everybody has a chance to write a comment about everybody’s art. That’s one of the biggest draws. Guys love to get paid for their art, but they also want to see the comments. They want to know somebody looked at their art and took the time to be like, “Hey, this looks great.” It’s just a great feeling to see guys get that positive reinforcement, just a little nugget of it, and watch them work through the rest of the year for the next show. It’s a really powerful thing.

Yaya: Absolutely. I’ve seen the light go out in people’s eyes, but I’ve also seen the light turn on. I know what it means for the lights to go on inside somebody’s eyes and in their heart. To see that transformation of the person, that’s been the most important thing for me. I love beautiful art. I love meaningful art, powerful art. But equally, I love seeing people transform and change and become better. We had guys on our programs who were innocent. They were the victims of a system. But these guys also discovered parts of themselves and were able to, while in prison, use the survival tool of art to continue to grow themselves and not be swept under the vicious nature of what incarceration can really be.

Decarceral thinkers and doers

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

etta: Both of you have participated in a bunch of different programs, including the Mural Arts Philadelphia program and the Michigan Prison Creative Arts Project, and then all of these art shows you’ve been in. Can you say more about the impact of these programs? What is the importance of doing these inside-out art projects?

DJ: I participated in a program that brought sixteen Michigan artists and sixteen British artists together for what they called We Bear. It was shown in Coventry, England, during COVID, and had 60,000 people go through there. It was so successful that they transplanted it over here for Art in the Park (a big festival near Ann Arbor). I never thought that I would get off my block, let alone have art in a show in England. It’s crazy where we’ve gone while sitting in prison. Supreme Court justice Sonia Sotomayor has one of my mentor’s pieces. A German supreme court justice has one of my other buddy’s pieces. When guys around us see that, it stirs that hunger in them to participate. To see them rise to the challenge of these programs and put out such powerful pieces—I wish there was more of it. I wish there was more recognition. A lot of these guys, they might not be the most well-spoken guys, but you put a paintbrush or a pencil in their hand and they will tell you a story of how they feel.

During my first four days out of prison, I went to the Detroit Institute of Art and got to stand next to Picassos and Vermeers. I was in a room full of Van Goghs and almost lost my mind. But I also thought about all the guys whose art I’ve seen over the years and I was like: This guy deserves a spot here. This guy deserves a spot here. This lady deserves a spot here. There are all these people inside who cannot believe that they have something to say just like these famous artists. We see it in a book and we want to attain it, but we just can’t quite cross the threshold.

Yaya: Yeah, that has a lot to do with people’s perceived notions about who they are and who they aren’t. These inside-out arts programs are 100 percent net positive in my opinion. I couldn’t imagine the prison environment without any structured arts programming. I don’t mean that in a pejorative way: there’s a great freelance and mercenary art culture as well. Tattoos, card makers—there’s everything, and they’re part of the community as well. We all share resources, we all compete, we all talk mess on each other. However, some of those artists may not necessarily participate in many of the structured programming, because their intent is to make money. That can be done in the structural programming as well, but they want a 24/7 hustle. That grind is not gonna accommodate sitting in a chair with fifteen other people talking about what they think a picture is. They’re like, Man, I could have made seven cards by now. But yeah, net positive. I think guys begin to put their energy into these programs instead of playing cards, checkers, and chess, which I have nothing against, but which are super leisure activities. Art is not a leisure activity. Art is a redemptive, powerful, meditative, actionable force within a person—within a human being.

DJ: It creates discipline in a lot of guys, too.

Yaya: Exactly, because you have to sit there and come up with an idea. Even to copy a picture takes a lot of focus, a lot of mental energy, and a lot of discipline. And you have to reach out. I can’t count how many times people have come to me and others, and said: Could you help me with this? I can’t draw this hand, I can’t execute this particular portion. How do you mix colors? How do you do this? Guys become able to humble themselves and take instruction. Also to be able to share what you know with somebody else, that’s all building community. The hours spent, the bonds being created between people who don’t know each other, people from different towns, from different cities, from different backgrounds, different ages, different races—all these barriers begin to dissipate and, in many cases, drop and disappear. People begin to form these new relationships through art, and through trying to achieve something within themselves that they will also share with others. Even sometimes just sustain themselves, which is just as much a reality as anything else.

In a carceral environment, the artist is one of the most respected. In general, if you go into any prison day room or prison cell and you start drawing, people gonna come up to you and say, “Hey, man, you got talent.” And then the next move is, “I need a picture drawn of my daughter, it’s her birthday.” That artistic power has a currency that can really be the essential DNA of the community. Fortunately, I was in an environment where we had a bunch of guys on that same code, who understood that our journey was to reap all the benefits of making art, but also to build a sustainable community of artists that could work together. We’re human beings. We celebrate each other, we talk trash on each other, we get on each other’s nerves, but at the end of the day, we back and we painting. We’re working together.

DJ: Like you said, in a lot of places you’re doing this in a day room. I was fortunate enough to land at a spot for a number of years that had an art room. Our teacher was a former Harlem Globetrotter, Herschel Turner. He was this big angry grandpa, but he could really draw, he was great with his pastels, and everyone really respected him. We were all under Herschel Turner like a bunch of little ducks, just following him around. Every crumb he dropped, we were listening.

Unfortunately, the state ended up pushing Turner out when he was just trying to help the guys. That left us in control of that environment. In the seventeen years that I was part of that environment, I can’t recall an argument, a fight, any kind of nonsense happening in that room. That was a sacred place. Guys didn’t always like each other, but we went in that room and we respected each other. We shared resources, traded art magazines. It was just a beautiful thing. I was running two airbrush classes a week, trying to get my artwork done, and working forty hours, but whenever someone asked me something, whether they were just starting out or were more established, I always felt a sense of pride that they would come to me.

Of course, you have to deal with the prison limiting your art supplies. They don’t want you doing this. It was mind boggling—just out of pure spite. They didn’t want us to grow. But we found our ways to grow, whether it’s pencil, guys drawing on typing paper, painting with coffee, whatever. We find a way. That’s the beauty in it for me, because if you can find the way to learn art, you can find the way to learn everything else that you need to get your ass out and stay out. How I see it, I’ve used the discipline that I learned to become a prison artist to come home and be a hard worker whom everybody in my community loves. I mean, everybody in my neighborhood has adopted me. They love me. Though they know that I did a horrible thing when I was a kid, it’s not like these people on TV, all that “get that asshole out of my neighborhood” stuff. And the thing is that there are more people like that in prisons, the light’s just got to be shone on them. If you could meet some more of these guys and understand their stories, it would blow you away.

Yaya: I totally agree. Prisons are completely irredeemable. I reached that conclusion quite a while ago, and that’s not a gleeful thing to say. We would hope that people in charge could create an environment which would rehabilitate those who need it. Unfortunately, the vast majority of the real rehabilitative effort is left up to the prisoners themselves, with a few determined people who provide support from the outside or venture within the prison to lend their abilities. But a very mighty but small contingent of people are actually the ones executing the rehabilitative effort we’re seeing across the country. Rehabilitation happens in spite of the system, not because of it. Prisons do not want to be redeemed.

We looked at us artists as the center of the prison petri dish, because everybody always comes to us and asks us for stuff or wants to work with us. So we said, in order to prevent losing the goodwill that we have with the administration and institution, we need to interlock our program with every other program that is functioning on the same wavelength as we are. You had the Fathers and Children Together program run by an organization called United Community Action Network. We linked with them. Not in a subordinate fashion, but as equals. We linked with the Temple University inside-out college program. We linked with Villanova University. We told them: Listen, we admire all the work you do. Any type of banners or anything you guys need, you will have it from us. You want a banner for your alumni association? We’ll do it. You want a banner for an event you’re having? We’ll do it. In return, we need you to share with us the support and goodwill you’ve garnered. And we’ll do the same. So it became extremely hard for the institution to resist us in doing anything we wanted to do because of all these strategic partnerships we created within the prison.

An unforeseen effect of this was that it increased the connectivity between the outside partners as well. Mural Arts Philadelphia people began to connect with the Fathers and Children Together program, with Temple University and the inside-out program. Outside partners began to form their own relationships as well, which were also beneficial to them. All the extended family, I would call it, became connected to the outside partners in a stronger way. I always looked at it like dreadlocks, you know what I mean? We be tied so tight together we couldn’t be pulled out.

Header image: Creative Resistance/Let’s Get Free