Tewkunzi Green is a community educator at the Illinois Prison Project. In this role, Green helps families of incarcerated individuals navigate the prison system and the process of release, providing crucial support and knowledge. Green herself served more than 13 years in prison. In 2007, she was the victim of intimate partner violence and, in an incident that occurred while she was holding — and feared for — her newborn son, she stabbed her partner, the father of her son, resulting in his death. She was sentenced to 34 years in prison. With the support of the Women & Survivors Project at the Illinois Prison Project, Green sought clemency. Governor J.B. Pritzker granted it to her, commuting her sentence and leading to her release in November of 2020. During her time in prison, Green remained a dedicated mother to her son, actively involved in supporting and encouraging him in his day-to-day life. She worked in the visiting room where she used her interpersonal skills to navigate complex emotional visitations and support other incarcerated mothers. She also worked to raise awareness about domestic violence within the prison. On October 15, 2021, Premal Dharia spoke to Tewkunzi Green over Zoom. Portions of that conversation have been edited and condensed for clarity to form the below narrative, as told by Ms. Green.

Rachel White-Domain, who runs the Women & Survivors Project at the Illinois Prison Project, was the lawyer who helped with my clemency petition. I was one of the first clients represented by the project because Rachel had been my lawyer for years, even before she started working at IPP. They started the Women & Survivors Project because I’m not the only one. There are so many other women like me who need help with their clemency and post-conviction cases, whose stories are not being told right now. And something I learned in this process, working with Rachel, was that the work of putting together the clemency packet, the details you pull up and the putting together of the puzzle pieces of your life, it gives you your story. Clemency gave me my story in many ways.

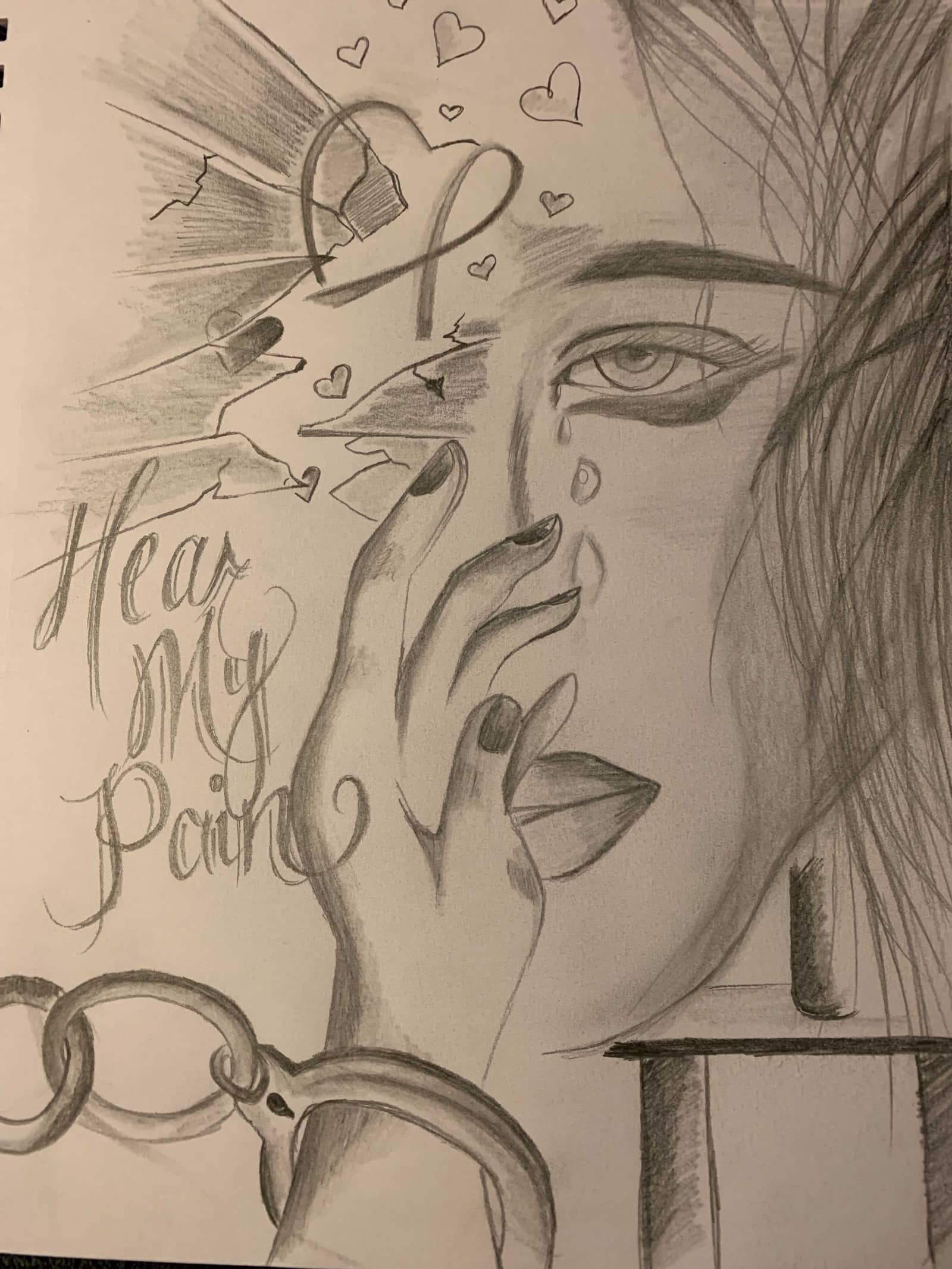

Especially for mothers who have kids out there, what it means to show yourself, to show why you need a second chance to rejoin society, is so important. Some people take clemency to be just a one-way ticket out. But for me, and for lots of others, clemency is more than that: It is a second chance, a second chance to show people exactly who you are, and that you make a big difference to the people in your life. For me, it was a chance to tell my truth — a truth I’ve been made to feel the courts do not want to hear, especially having gone through a sentencing hearing that led to a sentence of 34 years. With clemency, I was asking, “Can somebody hear my voice?” And then, with the success of our efforts, I felt it made me visible. That clemency made me visible after the courts and prison had made me feel invisible.

Now, I spend a lot of my time working with families. I educate them about the process; I fill in gaps in knowledge. I tell them about clemency. A lot of people have loved ones in prison and don’t know where to start. I connect families with resources, with legal clinics or other resources. When I came home from prison, I started doing a lot of speaking and community engagement. I started working with Love & Protect and Survived & Punished — movements and coalitions that support survivors of interpersonal and state violence. I joined the Illinois Prison Project because of this engagement. I was speaking out on what it means to be free, what it means to survive something so traumatic. And others thought my words and experiences and advocacy could help even more people out there.

My truth is that I was in hardship for years. And now I understand where I need to get to in life. But the system didn’t give me that chance when it had the chance to. It just slapped cuffs on me. It just took me away. It just made me invisible.

The chance to speak out has been really important to me because when I speak, you hear the real me instead of what you assume that you know about me. This gives me a chance to say, “Hey, I’m not the person that you might think I am.” I’m more visible to myself now. I am visible to my son. My truth is that I was in hardship for years. And now I understand where I need to get to in life. But the system didn’t give me that chance when it had the chance to. It just slapped cuffs on me. It just took me away. It just made me invisible.

That impacted everyone. Not just me. That impacted my family. I was hurting. I am hurting. I’ve been through too much hardship. This clemency is going to be the way that I show them, “Hey, I wasn’t the person that y’all said I was.”

My son was 14 years old when I came out of prison. I never got a chance to see anything — anything of what he went through in life until then. He was 6 months old when I was incarcerated. And I could only express so much from behind the wall.

I was incarcerated at Logan Correctional Center here in Lincoln, Illinois. It’s an all-female facility. The staff was majority men. The administrators, like the wardens, they were more women. But if you count the officers, we had more male officers than we did female officers. Being in a prison run mostly by men, it was very clear that they don’t understand women. The women that were running it, they were focused on getting us to understand the rules and regulations when you come to prison — like, stand in line the way you’re supposed to, make sure you dress appropriately. But the men — they want to degrade you. They tried to maintain power and control by degrading us. There was a lot of verbal abuse. They called us monkeys, assholes, bitches. But of course, when you speak back you get in trouble for it. It was like they were trying to take the little bit of freedom left within me in order to just demolish me. The system had already taken what it could take from me, and then you come into a place like that and people don’t understand how they are taking away what very little there is left. Do this. Do that. They took everything, and then they wanted to take my dignity from me. I almost felt bad for some of them sometimes, and for the people in their lives at home. They used so much energy and power to degrade us. What happens when they are at home, with their families and with their children? Who else will they degrade?

My son will be 15 soon, and it’s been really special and exciting to be close to him. We are really close. He’s amazing — I am so proud to be his mother. He has good grades. He plays football and is one of the best on his team. He’s a wide receiver. Every weekend, he has at least a touchdown and more than five tackles. And he keeps mostly As on his report card. A lot of children with incarcerated parents struggle, and I am so grateful for how he has grown.

He turned 6 months old the day I went to jail. It was very hard when I left him. He needed me; it was just me and him. He had a sister and brother on his dad’s side, but I still felt like, “That’s my only child.” And his father was gone. I missed seeing him take his first steps, and the first tooth that came out of his mouth, and the first day of kindergarten. I have missed a lot. But I have family who supported me and him, and who gave him things I could not at the time. And they brought him to the prison, so I could see him walk — you know, things like that that you miss out on.

The biggest change in my life, honestly, was that I had to learn my son from prison. And in the process of learning who he was, I was honest with him. I never made up a story about why I was in prison. I gave him the honesty he deserved. Basically, I had to be a real parent and have very hard conversations. I had to say, “Hey, this will happen. Your grandma will take you to school. Your aunt will take you to the doctor. I’m in prison.”

But he was the reason. The reason I needed to get home.

When you’re a survivor of harm and violence — when you’re still surviving — sometimes you deny yourself. There’s a lot of shame. And there are so many women in prison who deny themselves, who are survivors and surviving. There are a lot of nights in prison where you just play cards and talk. And you sometimes get into deep conversations about your past. And one of the common themes is about people surviving. And being afraid: afraid of their own shame, afraid to be embarrassed about what has happened to them, afraid of the people that might label them, stereotype them, judge them. Or afraid that if they put their personal family business out there, that their families would abandon them.

The organizations I’ve come to work with — Illinois Prison Project, Love & Protect, and Survived & Punished — have been tremendous sources of support, not just for me but for helping me realize that I could talk about my experience and find support and even help others. So many of us are surviving — domestic abuse, harm in our families, relationships and communities, rejection, abandonment, and then also surviving mass incarceration. We are surviving everywhere. And that support is so important. It helps get at the deep shame.

So many of us are surviving — domestic abuse, harm in our families, relationships and communities, rejection, abandonment, and then also surviving mass incarceration. We are surviving everywhere.

You know, the word victim is so interesting. Take a murder case, for example. We talk about how the victim passed away. But then do we ever consider that the suspect may have been a victim as well? The criminal system doesn’t know how many suspects are victims — actually victims — in that situation. It does not get to define that I cannot be a victim. I’m not going to be invisible any longer. I’ve been invisible all my life. I’m proud now to make a difference. I’m proud to stand up and say, “I am visible now.”

Image: Unsplash