Popular culture tells us that profit-driven incarceration began in the South after the Civil War, that it was a way of re-enslaving African Americans after the end of southern slavery. This version of the story often connects to the Thirteenth Amendment, which outlaws involuntary servitude “except as a punishment for crime.” Scholars, including Daryl Michael Scott and Rebecca McLennan, have long known that, in fact, profit-driven incarceration originated in the North, not the South, and it began long before the Civil War. Forced carceral labor did begin in the wake of slavery, but it originated after northern, not southern, slavery. This knowledge has not, however, entered the popular consciousness. Robin Bernstein’s latest book, Freeman’s Challenge: The Murder That Shook America’s Original Prison for Profit, reopens northern prison history by vividly recounting the life of one individual, William Freeman, an Afro-Native teenager who challenged carceral capitalism at its root.

In the following conversation, Bernstein talks with Nicole Fleetwood, celebrated curator of the Marking Time traveling exhibition of work by incarcerated artists. It is based on a conversation between Bernstein and Fleetwood that took place at the New York Society Library, and which has been revisited for Inquest.

Nicole Fleetwood: Who was William Freeman?

Robin Bernstein: William Freeman was born in 1824 in the town of Auburn, in New York’s Finger Lakes area. Auburn was the place that invented the diabolical idea that a prison could exist primarily, fundamentally, to stimulate an economy. Profit—capitalism—was more important than justice. It was more important than punishment. It was more important than reforming people, helping people live better lives. That idea was invented in Auburn, New York, in 1816 with the establishment of Auburn State Prison.

Freeman was part of the most prominent Black family in town. His grandparents had been fundamental in establishing the town of Auburn. So he grew up in the shadow of this prison that had invented a new form of unfreedom, and he had a reasonably good life as part of a close-knit Black community. But in 1840, when he was fifteen years old, Freeman was accused of stealing a horse. There was no hard evidence against him, but it didn’t matter. He was tried, he was convicted, and he was sentenced to five years hard labor in Auburn State Prison.

The labor of people incarcerated in the prison was leased to local profit-driven companies, which had been allowed to set up factories inside of the prison. Freeman was set to work for these companies in these factories, working twelve hours a day for no compensation at all: no pay, no special privileges, no early release, literally nothing. And he was incensed. He resisted from the very beginning. He resisted by speaking up and saying that he did not want to work because he had committed no crime, and because he should be a free person. He also said that if he was going to work, he should be paid for his labor. He resisted in a lot of small ways while he was in prison. He resisted by doing things like working slowly and deliberately working badly. A lot of people were doing that. And then when Freeman was released in 1845, he struck out on a legal mission to recover what he saw as back wages that had been stolen from him. He had worked twelve hours a day for five years, and he felt that money was owed to him for this labor. So he went on a campaign to legally recover the money—and he was laughed at, and he was dismissed. And after six months of being laughed at and dismissed, Freeman murdered four people whom he knew only slightly. By committing violence that seemed random, rather than by hurting people who had directly hurt him, Freeman implicated the entire population that was profiting from the system of profit-driven incarceration. The quadruple murder was an act of terrorism that succeeded in terrifying the entire city and deeply threatening the Auburn State Prison: when asked to give an account for his actions, Freeman was clear that the prison had deprived him of wages and that if it would not give him back wages, he would have payback.

Freeman’s story is so important because it reveals the reality of profit-driven incarceration, and resistance to it, in the North long before the Civil War and the Thirteenth Amendment. If we tell the history of convict leasing beginning with the South, the Civil War, and the Thirteenth Amendment, we’re starting the story in the middle. The problem with starting the story in the middle is that when we do that, we’re letting the North off the hook. My broadest goal in Freeman’s Challenge was to put the North back on the hook.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Inquest, finalist for the 2025 National Magazine Award for General Excellence, brings you insights from the people working to create a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest in your inbox every Saturday.

Newsletter

Fleetwood: How did you come across Freeman?

Bernstein: One of my fields of knowledge is U.S. theater history, and I came across a footnote that said that, in 1846 in Auburn, New York, there had been a stage performance in which a Black character named William Freeman murdered white people. I thought, “Wait—how could that be on stage?” It was so surprising to me because in the mid-nineteenth century, white people absolutely did not want to see images of Black-on-white violence. It was too threatening to be entertaining. They wanted so badly not to see it that they used to doctor performances of Othello, because Othello has a scene of Black-on-white violence, and they would change Shakespeare to avoid that image. And yet, here were white people in Auburn lining up and paying to see this thing that white people everywhere else were running away from. What could have made them behave so differently from white people elsewhere? I realized that something race-shaking must have happened, and I had to learn more. So I pulled that thread. And I learned that the play staged a real murder committed by a real person, William Freeman. As I learned more about Freeman, I realized that he had something very important to say: profit-driven incarceration is wrong. People needed to hear it in 1846, and we need to hear it now.

Fleetwood: It’s profound because not only is this the period that creates the modern form of punishment, but also because Freeman is fifteen when he is sentenced and begins to make this brilliant critique of carceral labor.

It’s really important for us to think about this early prison holding the body in captivity, but also incapacitating people so that the system can exploit labor—and seriously impact the life expectancy of those who are incarcerated. So much of the current moment we’re in is still based on punishment, still profiteering from incarceration, still causing premature death.

Bernstein: Absolutely. Indeed, even the Auburn prison itself still exists. It’s now called the Auburn Correctional Facility, and it’s the oldest continually operating maximum security prison in the United States.

Cornell University has a wonderful program called the Cornell Prison Education Program, which enables people incarcerated in Auburn to earn an associate’s degree from Cornell. I’ve worked with the folks in this program for a few years. Recently, I was able to go in and meet with incarcerated students. My publisher, the University of Chicago Press, was incredibly generous and donated seventy copies of my book to currently incarcerated students. I was nervous that the books wouldn’t get in, because when you’re dealing with a prison, as you know, everything is arbitrary. The administrators can make up any rule at any time and do whatever they want for no reason at all. So I wasn’t sure Freeman’s Challenge would actually get into the prison.

But the copies did get in—three days before I visited. I met with the students, and it was incredible. Many of them had read the book cover to cover in three days. They had wonderful, smart, insightful things to say and to ask. I spoke with about forty students. For about half an hour, I talked about Freeman and his experience in Auburn. Then I opened it up and I asked them what parts of Freeman’s story resonated (or didn’t) for them.

Their answers focused on labor. People incarcerated in Auburn still work, and the prison is still built around factory work. Today, every license plate in New York State is made in Auburn. Any time you see a New York license plate, you should know that that individual plate was made by a man who literally walked in Freeman’s footsteps. A lot of the students said this: they talked about their experience of factory work in Auburn prison, and how it was similar to what Freeman experienced. More than one person actually said, “Freeman’s story is my story.” It broke my heart. They also talked about what you mentioned just now, Nicole—the shortening of lifespan. One incarcerated student said that he was upset about the fact that he knew his lifespan was being shortened by his time in Auburn prison. He spoke in particular about the nonnutritious food and the dirty air. Both these things were absolutely true in Freeman’s day. The food, then and now, does not sustain life. The air, then and now, is terrible. When Freeman was incarcerated, the top reported cause of death was tuberculosis, which was caused, of course, by contagion, but worsened by the smoky, awful factories.

Fleetwood: What were some differences between Freeman’s experience and current life in Auburn prison?

Bernstein: There was one thing that I assumed would be a difference, but it turned out to be a connection, and that stunned me. This was the use of silence. In Freeman’s day, the prison enacted extreme social isolation by forbidding people to speak—ever. It’s really hard to take this in, but it’s true: incarcerated people were not allowed to say a single word during their entire incarceration, unless it was a direct answer to a guard’s question. They worked together in factories in total silence, never speaking to each other; at night they were housed in single-occupancy cells that were designed to prevent conversation. This means that when Freeman entered the prison at the age of fifteen, he was told, essentially, “You are not going to speak another word until you are twenty.” It is so hard to take in that reality. Let’s be clear: this is torture. And the purpose of this torture was not punishment. The purpose was to squeeze as much labor out of these men as was possible. The purpose was productivity and capitalism.

That rule is no longer in effect. Today, people incarcerated in Auburn are permitted to speak in the factories. So I expected that they would say that this was a difference between their experience and Freeman’s. But they didn’t. Instead, they said that silence is still a weapon to control them and their work. They told me that at any time, a guard can call for total silence. When that happens, everyone needs to fall silent, immediately. This is an everyday part of the experience of working in the factories in Auburn prison. And the purpose is the same as it was in Freeman’s day: social control that aids productivity.

Nicole, you work with so many incarcerated and formerly incarcerated artists through your Marking Time project. Do you have a sense of how Freeman’s experiences would resonate for them?

Fleetwood: So many of the artists I work with, and have helped to exhibit, reflect on labor and captivity. James “Yaya” Hough, for example, has an incredible watercolor called I Am the Economy. It’s a Black male body being fed into a machine, and out of it comes dollars. He has another called How the Big House Makes Boxer Shorts. It’s about incarcerated people making underwear, being paid a pittance for it, and then having to buy it back at three to four times the cost. So it’s not only an exploitation of labor and the body and one’s life capacity, but then being forced as a captive audience into certain consumption practices. There’s a work called Institutional Nightmare, by Gilberto Rivera, where he incorporates wax floor because his job in prison was to mop the floor. He also incorporates the warden’s signature. So he incorporates all this materiality about his exploited labor into the work itself.

Kenneth Reams, another artist I work with who’s currently in prison, was on death row for twenty-seven years, the youngest person on death row in Arkansas when he was sentenced at the age of eighteen. He’s now about fifty and in general population, but he spent nearly three decades in solitary confinement, much of it on death row. He has become a prolific artist and activist from that space. He made a work called Capitalization. It looks at all the ways that corporations profit off of punishment—but also off of the loved ones who are trying to support the incarcerated person.

The artists I work with also resist in some of the ways Freeman did, like slowing down or doing the job poorly. The artist Dean Gillespie was in prison for twenty years for a wrongful conviction. Over those years, he said, “They were stealing the years of my life and I was ‘procuring’ their goods.” He uses “procure” as a euphemism for his unauthorized use of state goods in the service of art. He “procured materials” to make incredible works of art. So these forms of resistance are very similar to what you share about the way that Freeman would speak up, but also critique.

Bernstein: I’m so glad you brought up these very intentional, thoughtful critiques of the prison by the incarcerated artists you work with. One thing I wanted to do in Freeman’s Challenge was show how thoughtful and rational Freeman was. He was told over and over that his desire to be paid for his labor was “delusional.” But his point was anything but irrational. He was saying that he was a citizen, that he was not an enslaved person, and that he deserved to be paid for his work. I wanted to amplify that very important rational thought.

Fleetwood: I was so moved by how you talked in the book about Freeman being loved. I wanted to connect that to my own experience with having family members who are imprisoned. During one of my first public presentations of Marking Time, someone came up to me after my lecture and said, “I never thought about people in prison being loved.” It’s so important to foreground that because of what the stigma of incarceration does to the subject who’s being held in captivity. And the public perception of that is what sociologist Michelle Brown calls “penal spectatorship.” We’re supposed to look at incarceration as a way of justifying and reproducing its violence by saying, “Well, they must have done something really bad.” Removing people from sociality and intimacy can seem deliberate and simple, so it’s shape-shifting in the book when you talk about Freeman being loved.

Bernstein: Thank you for saying that. It’s true. Freeman was part of a beloved family. His parents loved him. And that was really important to me to say, because later on he was vilified. And he did commit murder. But Freeman’s family never stopped loving him. There was never a moment in Freeman’s life when he was not loved.

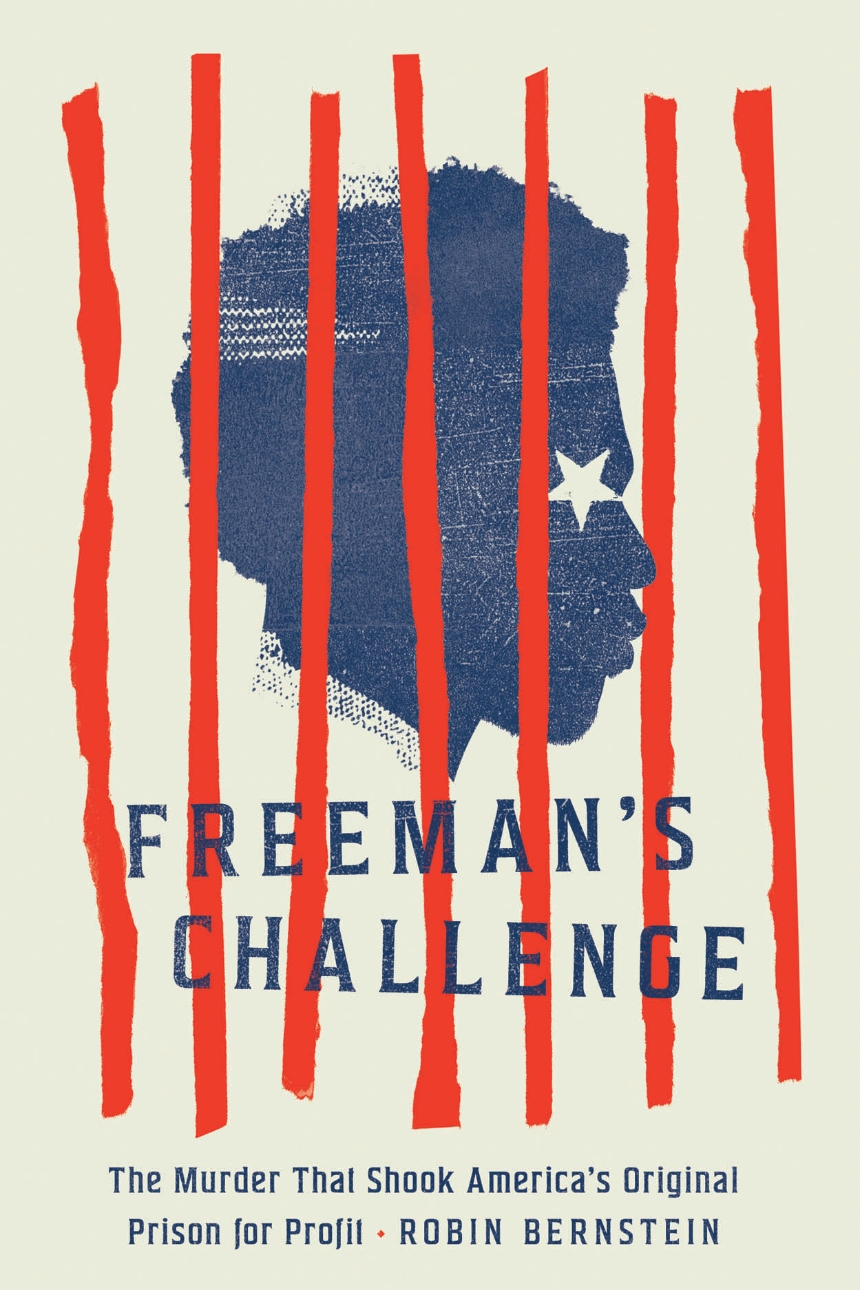

Image: Stereoscope image of the front yard of Auburn State Prison sometime before 1930, probably around 1850. Credit: Public domain, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library Digital Collections.