The war on drugs has played an outsize role in fueling the racial disparities of mass incarceration. By the end of the twentieth century, African Americans and Latinos accounted for two-thirds of incarcerated drug offenders. This is in spite of the fact that during the same period, white Americans constituted a large majority of illegal drug users and dealers, and broke the law at identical or often higher rates than nonwhite groups.

Understanding how this disparity occurred requires that we consider how the public drama of the war on drugs played out in affluent suburbs. White youth have long represented in the American imagination the most sympathetic and innocent victims of the narcotics trade. Likewise, they have been identified, by pundits and lawmakers, as the most resonant justification for punitive legislation against drug dealers, and they have been the chief beneficiaries of public health prevention and rehabilitation programs, often in lieu of incarceration. The war on drugs has continually flourished as a bipartisan crusade thanks in no small part to these racialized tropes of the person-of-color urban pusher and foreign trafficker, set against an idealized white suburban victim.

In the following, I explore how these themes have played out in public life and been constitutive of the racial disparities of mass incarceration.

In the 1950s, a series of mandatory-minimum narcotics laws were enacted in the bellwether state of California. This would eventually be taken up at the federal level, and then expanded dramatically into a national anti-drug crusade with Nixon’s 1971 declaration of war on “public enemy number one” and the much-copied 1973 Rockefeller Drug Laws which targeted Black heroin dealers and addicts in New York City.

The fact that California’s early war on narcotics escalated was in large part thanks to grassroots suburban pressure, not simply top-down elite machinations. White suburban organizations representing more than a million residents mobilized to demand this crackdown on Mexican and Mexican American “dope pushers” who allegedly supplied marijuana and heroin to innocent teenagers. The state produced more than half of all drug arrests nationwide from the 1950s through the mid-1960s, and then the number of white middle-class youth detained on marijuana charges began to skyrocket.

California’s mid-century suburban white teenagers and young adults usually acquired illegal drugs by crossing the Mexican border themselves. They distributed and consumed marijuana as well as illicit amphetamines and barbiturates through casual networks based in beachfront areas and other centers of youth subculture. The political system and its criminal legal arm responded by devising a complex array of formal and informal policies. Building on the total statutory discretion, and deep racial and class inequalities, of juvenile delinquency controls, it arrested and then channeled these white middle-class youth into rehabilitative programs. But California’s war on narcotics had negligible effect on either supply or demand, and by the late 1960s between a third and a half of white college students and older teenagers in affluent California suburbs had broken the felony marijuana law.

The most remarkable and underappreciated feature of the war on drugs in white middle-class America is hidden in plain sight. The annual crime reports published by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the California Department of Justice show that between the mid-1960s and the late 1970s, the proportion of white Americans arrested on drug charges reached historically high levels and the percentage of apprehensions in the suburbs quadrupled, primarily because of targeted enforcement against surging recreational marijuana use among teenagers and young adults. By 1973 white Americans accounted for 81 percent of all drug arrests nationwide and 89 percent of juvenile apprehensions, which approximated their population share. This represented an unprecedented intervention by the carceral state as it scaled upward and geographically outward in the quixotic mission to criminalize and control the youth subculture through an enormous increase in marijuana arrests.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

The crackdown was an exceptional political experiment, exceeding the scope of alcohol prohibition enforcement in the 1920s, aimed at testing whether criminal law could deter white youth from smoking pot—and, if not, whether coerced rehabilitation worked. It’s necessary to exercise caution in utilizing the FBI’s unreliable and politicized crime data, especially because the arrest category illustrates criminalization and discretionary enforcement rather than actual “crime,” much less convictions, and also because the white category encompasses most Hispanics. Even still, the mass criminalization of white middle-class marijuana users was an extraordinary development in the U.S. war on drugs (though it is important to note that the incarceration of African Americans remained disproportionately high).

For the millions of white teenagers and young adults arrested in California for drug violations during the 1960s and 1970s, the criminal legal system left few official traces of their illegal activities. It was an astonishing, concerted act of bureaucratic discretion by the state’s most local agents. This, too, would become a model for the national war on drugs, which has, by explicit design, undertaken what Khalil Gibran Muhammad labels the “masking of crime among whites.” There are extensive and deliberate silences regarding how illegal drug markets and discretionary law enforcement actually operated in white middle-class suburbs.

Despite this, it is possible to reconstruct some of these silences to understand the scale of arrests and diversions to mandatory drug treatment. Police and probation departments frequently provided governors and legislative committees with summaries of enforcement operations as well as detailed internal studies of the discretionary processes of diversion and disposition following arrest. Agencies such as the California Department of Justice published extensive annual reports breaking down aggregate data on drug and delinquency arrests, probation, diversion to rehab, prosecution, and incarceration by categories such as race, gender, and geographic location. Federal agencies funded academic surveys of illegal drug activity among college and high school students as well as multiyear studies of “Drug Abuse in Suburbia” by probation departments that tracked the discretionary disposition process following arrest.

These sources reveal the broader patterns for white middle-class youth who encountered a drug-war apparatus that sought to deter, rehabilitate, occasionally confine, and most of all to protect them from their own actions without the stigma of a criminal record. In affluent suburbs, police and delinquency authorities almost always released college-bound youth to the custody of their parents, leaving no official record, in exchange for informal commitments to internal family discipline and often private psychiatric counseling. When this strategy failed to stem the illegal drug culture, police departments intensified profiling of white marijuana users based on age, gender, and “hippie” appearance. Surging arrests created a quandary for prosecutors and juvenile judges who wanted to deter their felony activities without inconveniencing middle-class futures with a permanent criminal record.

Many white youths pled down to alcohol-related violations, such as public intoxication or disorderly conduct, and others agreed to enter treatment programs under threat of prosecution. But the criminal legal system simply dismissed a majority of marijuana possession cases by the late 1960s. The futility of this approach of scaring white youth into obeying the law through felony arrests without consequences led to the federal- and state-level misdemeanor possession reforms of the early 1970s. This approach still involved discretionary justice but had considerably harsher outcomes for tens of thousands of recreational pot smokers defined as “sick people” and “drug abusers” and forced through probation into mandatory rehabilitation programs. Growing anger about the carceral state’s crackdown on marijuana crimes by “otherwise law-abiding” youth inspired popular campaigns for legalization and decriminalization supported by the ACLU and the interest group NORML, which each operated within “political whiteness” by reserving true victim status in the drug war for these middle-class and suburban Americans.

The suburban zero-tolerance movement that reinvigorated the federal war on marijuana during the late 1970s and 1980s blamed the increase in pot smoking among younger teenagers on the “permissiveness” of decriminalization. But the Carter and Reagan administrations also remained within its racial and spatial boundaries by prioritizing public health policies of prevention and private-sector rehab for white middle-class suburbs while intensifying crime control enforcement against heroin and later cocaine markets in nonwhite urban centers. As the FBI data reveals, the drug-war interregnum came to an end during the militarized assault on urban crack markets following passage of the bipartisan Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, and the arrest proportion of African Americans returned to the level of the early 1960s though at an exponentially greater scale.

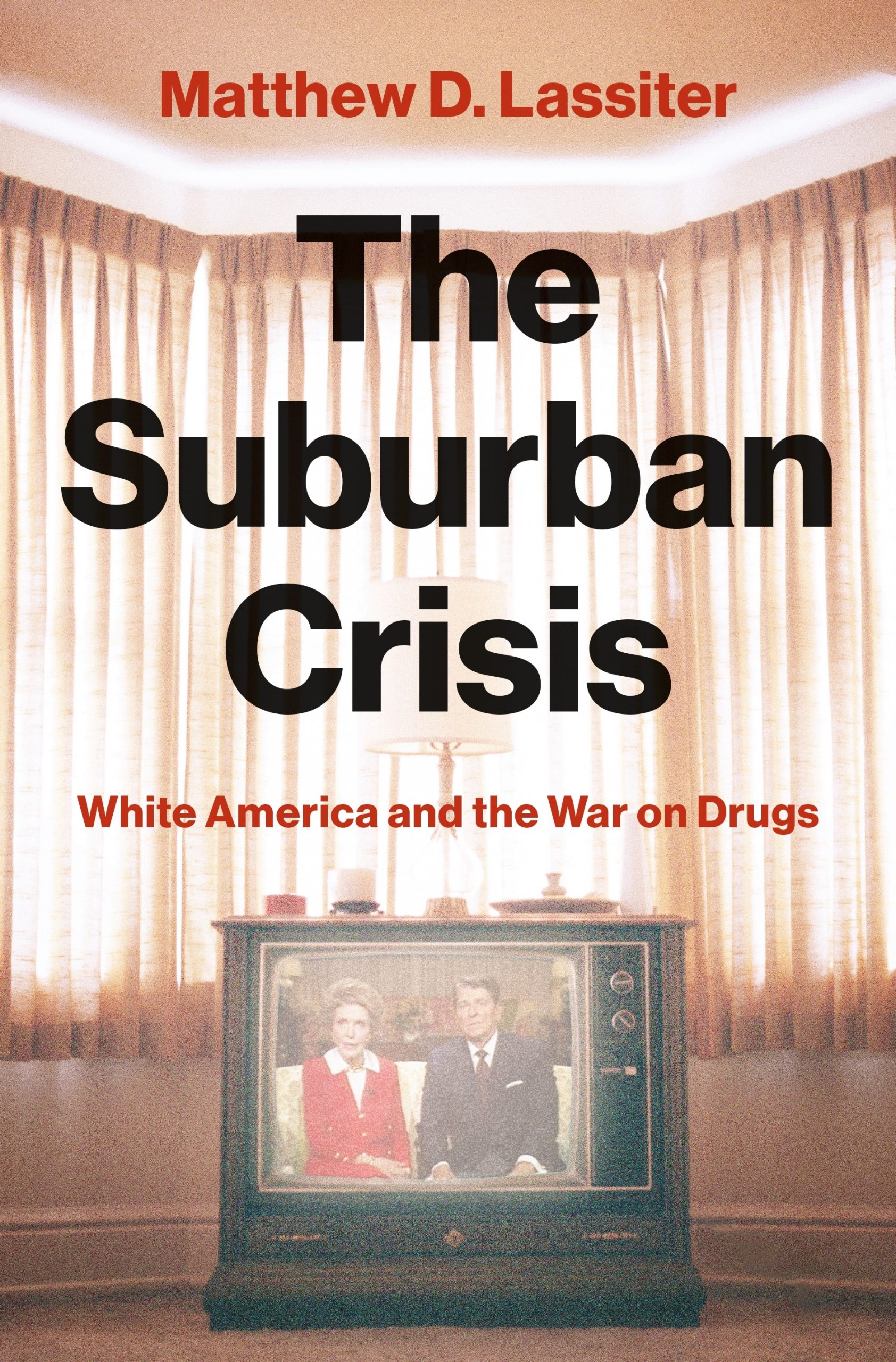

Excerpted from The Suburban Crisis: White America and the War on Drugs by Matthew D. Lassiter. Copyright © 2023 by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission.

Image: Tristan Gevaux/Unsplash