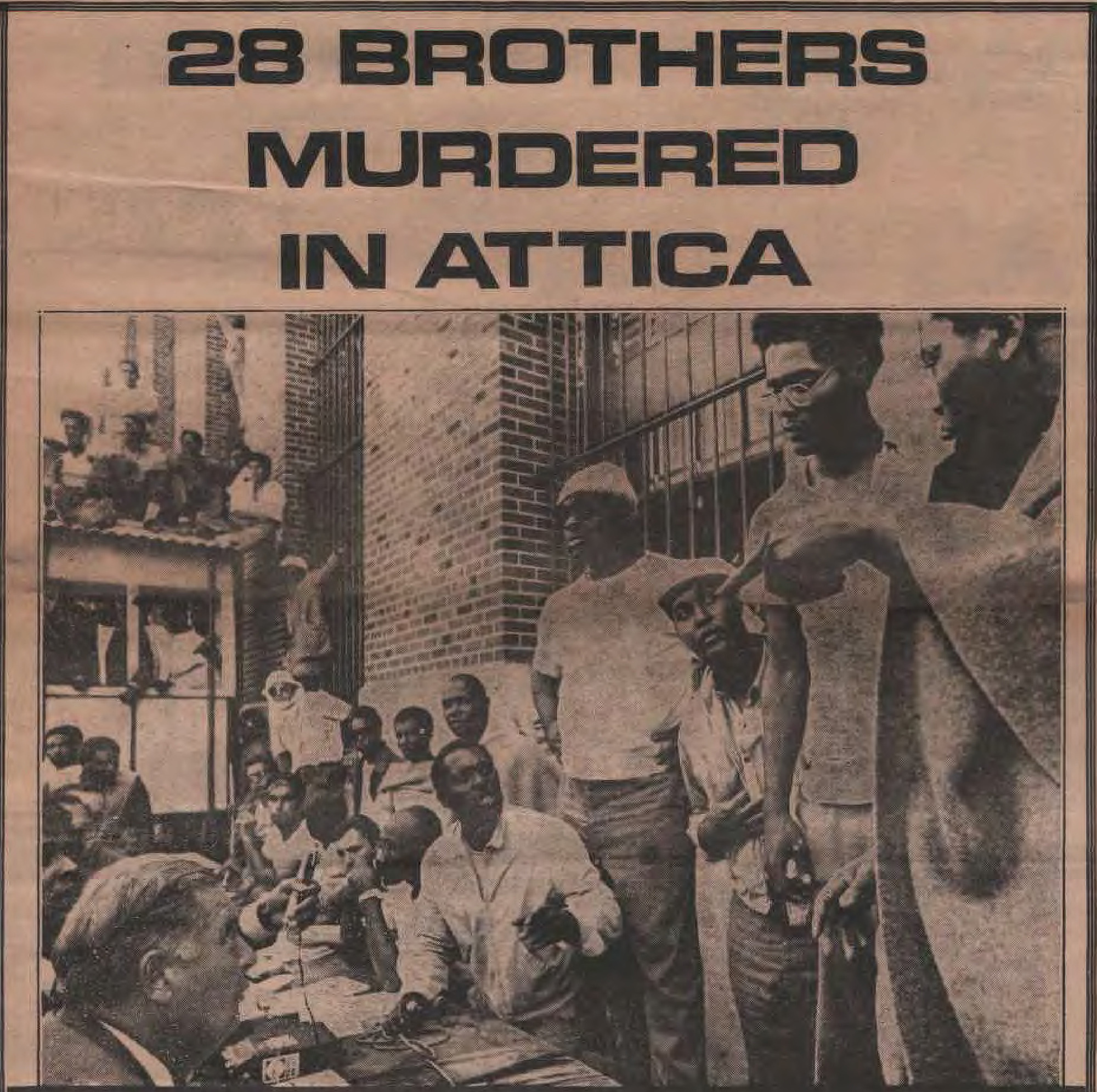

“The very day of the Attica takeover,” said Emily Goodman, “I happened to be at the Guild office when [William] Kunstler’s call came, saying that the place was going to blow up and that lawyers, and probably doctors, were needed. I was one of the lawyers who went there immediately.” They flew to Buffalo in the afternoon of September 13 and prepared the papers to obtain access to the prison through a federal court order. When they arrived, there was already a small contingent of attorneys and legal workers from Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia, and New York who had rushed to Attica on September 11, 1971. Two days earlier, prisoners there had seized the facility and taken forty-two guards and civilian employees hostage, catalyzing what would become the most dramatic prison uprising in U.S. history.

“But, when we got there by car,” Goodman recalled, “we realized that our court order was not worth anything. We found armed police and military. A person checked our papers. I said: ‘I have a court order.’ He said: ‘I got a bayonet.’ That was a startling moment, not only for me but also for other people. We went to law school, we believed in lawyers, court orders, judges. That gave us some power. But that was one quick lesson about how little all that meant.”

Denied access to the prison by the warden, the lawyers spent the night outside the gate. They were still there the morning after, when medical analysts said that all the prisoners had been shot by government agents. Rage escalated, but the Correctional Services Department still denied access, allegedly for security reasons. On September 17, only lawyers, without medical personnel, were allowed to step into the prison. The National Lawyers Guild immediately sent five persons to interview prisoners and preserve evidence, which ran the risk of being contaminated. In the meantime, the Guild sponsored the first class-action lawsuit on behalf of the Attica prisoners to compel the State of New York to institute criminal prosecutions against Rockefeller, Oswald, Attica warden Vincent R. Mancusi, and other state police and correction officers for committing, conspiring to commit, or aiding and abetting in the commission of crimes against inmates and guards at Attica.

Guild lawyers were not alone at the prison. The Legal Aid Society, the ACLU, and the Council of New York Law Associates had also been present, feeling the urge to provide their support. But since the very beginning Guild lawyers differentiated themselves by regarding inmates as “political prisoners.” They sought to capture their political claims and channel them into a common strategy—something that other, more neutral legal organizations disregarded. Guild lawyers also promised to identify with the defendants’ plight. As a dense correspondence confirms, many of the inmates, who lamented persisting intimidation, dehumanization, and victimization, specifically requested the exclusive “commitment” of Guild lawyers in mounting “a total defense.”

By January 1972, a loose coalition of legal groups had formed under the aegis of the Attica Defense Committee (ADC). The ADC aimed to raise funds, provide legal services to cases arising from incidents related to prison conditions, pursue affirmative legal actions for the rights of detainees, and disseminate information on prisons. “To forestall feelings of isolation and hopelessness,” the ADC also pledged to foster links between the movements inside and outside prisons, thus creating a broader base of support for inmates. Legal workers, former prisoners, concerned citizens, and students joined the group in addition to lawyers.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

Surviving prisoners had been the objects of brutality and humiliating retaliation in the days after the takeover. They were stripped naked, beaten with clubs, threatened, kept in solitary lockup, and denied elementary rights. Guards also confiscated or destroyed most of their personal property. In response, Guild lawyers filed several suits to denounce these punitive treatments. In conjunction with other groups, the Guild also filed motions challenging the special Attica grand jury, which was seated in Warsaw, New York, to investigate the events. They unsuccessfully contested both its venue—the County was a predominantly white and conservative area where the prison was a major employer—and its composition, which was, unsurprisingly, all white. A speaker’s bureau was also created to inform the public about the development of the case, its main goal being to present the inmates’ view of the rebellion and counteract the false reports that abounded from both official sources and the press. They were among the very few who denounced the campaign of systematic disinformation that, years later, would emerge.

William Kunstler, an attorney for the NLG, spoke at the State University of New York at Buffalo the day after the takeover. He described Rockefeller as a “murderer” and called for his resignation. The “real murderers,” he declared, “wore uniforms” and “had state-issued weapons and ammunition.” Dan Pochoda, another Guild lawyer who had been at Attica since September 13, reported how he was inspired by inmates’ courage, perception, political understanding, solidarity, and will to resist. He was taught “that a person must resist the forces of oppression, of racism and exploitation in every context, that a person must constantly fight the humiliations and indignities or die.” An act of resistance at the highest level, Attica had shown that “an effective, multiracial organization under third-world leadership” was able to take control “in the most controlled of institutions” and to expose worldwide that America’s rulers were liars and murderers.

After thirteen months of hearings, the special Attica grand jury handed down its initial thirty-seven indictments in December 1972. Sixty Attica Brothers were charged with crimes ranging from murder to possession of a prison key. Only prisoners were indicted. The ADC immediately accelerated the recruitment of lawyers, so that any defendant could have a trusted attorney instead of a court-appointed counsel and demanded that the state officials responsible for the conditions that led to the revolt and for the “mass murder” be brought to justice. The committee also urged sympathizers to “pack the courthouse” to demonstrate their solidarity with the Attica Brothers and to show the authorities they were being watched.

A few days later, when the arraignments took place in Warsaw, prisoners declined to enter pleas and, to dramatize repression, refused to walk into the courtroom, often forcing prison guards to drag them. The defendants turned to their supporters in the audience and rhetorically asked them if they—the people—had indicted them. The answer was a loud “No!”

There were serious difficulties for the lawyers hoping to defend those charged in the aftermath of Attica, however. The defendants were numerous, and the ambitious pledge to “get every brother a lawyer” had to be honored, together with the commitment to preserve “a unified resistance against the prosecution.” Many experienced attorneys were needed—not just the activists and legal workers who represented the majority of the volunteers. But despite their generic proclamations of solidarity, few lawyers wanted to get involved in the complicated cases that were to be tried in a remote place over a period of many months. The ADC could make no commitments about covering expenses, let alone fees.

But beginning in mid-June, lawyers, legal workers, and law students gathered in a two-hundred-year-old farmhouse in Victory, New York, to work on the defense effort. The group was aware that it faced “one of the most massive political prosecutions in [the] country’s history.” Nevertheless, disorganization, divergent political outlooks, lack of resources, sexism, and elitism seemed to put a spoke in the Guild’s wheel. Donald A. Jelinek, the group’s first coordinator, recalled having a hard time dealing with the younger volunteers, describing them as “callow sloganeering young crusaders.” According to him, they had alienated community organizers, refused to be directed by seasoned lawyers, and advocated a “suicidal” politicization of trials.

This old-time contrast between radicals and moderate leftists risked compromising everything. But that strange communal house did not collapse, and by the fall, attorneys from all over the country were rushing to the Brothers’ aid, ready to file pretrial motions and to investigate state claims. By September 21, the original Defense Committee had morphed into the Attica Brothers Legal Defense (ABLD), which explicitly combined legal and political goals. Based in New York City, the ABLD built branches in Victory, Buffalo, Syracuse, and Rochester, New York, as well as in Detroit, Chicago, and Berkeley. Its staff included eighteen defense attorneys and at least twenty-eight investigators. Funds finally began pouring in, mostly through community groups such as FIGHT (Freedom, Integration, God, Honor, Today) and BUILD, and through lawyers’ networks, such as the Association of the Bar of the City of New York.

Since the task seemed colossal—the legal defense planned to contact over four thousand witnesses, volumes of physical evidence had to be sorted and filed, and a massive jury selection needed to be prepared—during the summer of 1974 the Guild sent another twenty law students to New York and Buffalo to assist the ABLD, and also to contribute to community network and fundraising.

The trials began in September 1974, after a $4 million state investigation that involved twenty specially appointed attorneys general and required three years of work. The hardest challenge for the ABLD was to fashion and keep together a common political strategy for the Brothers—a strategy that combined militant goals and effective judicial outcomes without loosening the solidarity pact among defendants. There were two dominant legal philosophies that emerged: Moderates intended to discharge inmates by demonstrating their innocence on legalistic grounds, whereas radicals were eager to mount an aggressive political campaign to put the state on trial and justify inmates’ violation of the law as a response to the barbarous conditions of imprisonment.

In many respects, this reflected the diversity of opinions among the Attica Brothers. Some of them preferred to be discharged or avoid political contention, while others were ready to assume considerable risk to denounce state brutality. Some opted for entrusting their lawyers with all responsibilities, while others, usually the most politicized, claimed a more active role and typically demanded to act as co-counsel. Still others directly contested the “white leadership” in the legal field and invoked self-defense.

As always, the enhanced commitment of lawyers brought together discussions and divisions. Trial strategies varied—and so did their outcomes. Bilello refused radical lawyers’ help and pleaded guilty in the very first Attica case that went to court. In the prosecution for the death of officer Quinn, for which two Native American prisoners John Hill and Charles Joe Pernasalice were indicted, diverging lines of defense emerged. William Kunstler and his girlfriend Margaret Ratner defended Hill with an openly militant strategy, seeking to politicize the case as much as possible. He participated in street demonstrations, insisted on denouncing state violence, decried the neglect of prisoners, and vehemently challenged the jury selection. He referred to Hill by his Indian name, Dacajeweih; wore Indian ornaments in the courtroom; and beat an Indian drum outside the building for press. At the same time, Hill showed up with a ribbon in his long hair and was escorted by a claque of tribesmen, including Mad Bear, a spiritual leader who sported traditional garments. Kunstler concluded with a poignant seven-hour summation that needed an additional day to be completed.

However, the judge systematically denied defense motions and barred any evidence that was not strictly related to the murder. Only faltering evidence linked the two inmates to the actual beating that left Quinn dead, but the jury found Hill guilty of murder. He was sentenced to twenty years to life. By contrast, Pernasalice, who was represented by Ramsey Clark, Herman Schwartz, and others with a more traditional, by-the-book approach, was sentenced to second-degree attempted assault and received an indeterminate sentence of up to three years.

As Kunstler’s biographer, David Langum, noted, the temper of America in 1975 was far more conservative than it had been during the Chicago Seven trial, and the case of Attica failed to catalyze the same level of sympathy and mobilization, even on the Left. This remained the case even after Malcolm N. Bell, a chief assistant prosecutor in the Attica case, spoke to the New York Times in an expose. Bell told the world that the prosecutors who investigated the revolt had systematically prevented any legal action against the law enforcement officers who ended the siege, despite a large volume of evidence against them. “I couldn’t call witnesses, I couldn’t ask questions, I couldn’t pursue leads,” he protested, suggesting that authorities had pushed for a coverup.

These complaints of “fabrication and selective prosecution” were hardly isolated. But before anyone else had mentioned them, the ADC had been denouncing them. Its lawyers had spelled them out in court, and later two state commissions had reiterated them. Even state legislators questioned why only inmates had been indicted, whereas state troopers and guards had been left out of any prosecution. Eventually, it was no longer possible to overlook the facts. By December 1976, Governor Carey halted all prosecutions, issued a pardon for some Attica inmates, and commuted the sentence for John Hill, who would be eligible for parole shortly after.

A bittersweet feeling pervaded Guild lawyers and activists. Former prisoners and their families, as well as hostages’ families, felt they had been denied justice and lamented that authorities had forgotten them. But the story did not end with Carey’s actions. In the early 1990s, a former prisoner, Big Black, brought attention to the fact that a class action, filed in 1974, which sued the governor and other state officials for damages, was dormant but still alive.

Twenty years after the revolt and with little hope of winning anything, Elizabeth Fink decided to reopen the case. With Black, she set up the Attica Justice Committee, and with the help of other radical attorneys and volunteers, they won a historic decision establishing that the civil rights of Attica inmates had been violated and that the state had to refund them. A settlement was reached only in January 2000, when the state finally agreed to pay $12 million, to be apportioned between prisoners and attorneys. Since some prisoners were not being adequately compensated, lawyers gave up a portion of their share. Although the state never admitted wrongdoing nor issued official apologies, defense lawyers and militants could stand tall. They had not fought in vain.

From Up Against the Law: Radical Lawyers and Social Movements, 1960s-1970s by Luca Falciola. Copyright © 2022 by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by permission of the publisher. www.uncpress.org

Image: Washington Area Spark/Flickr