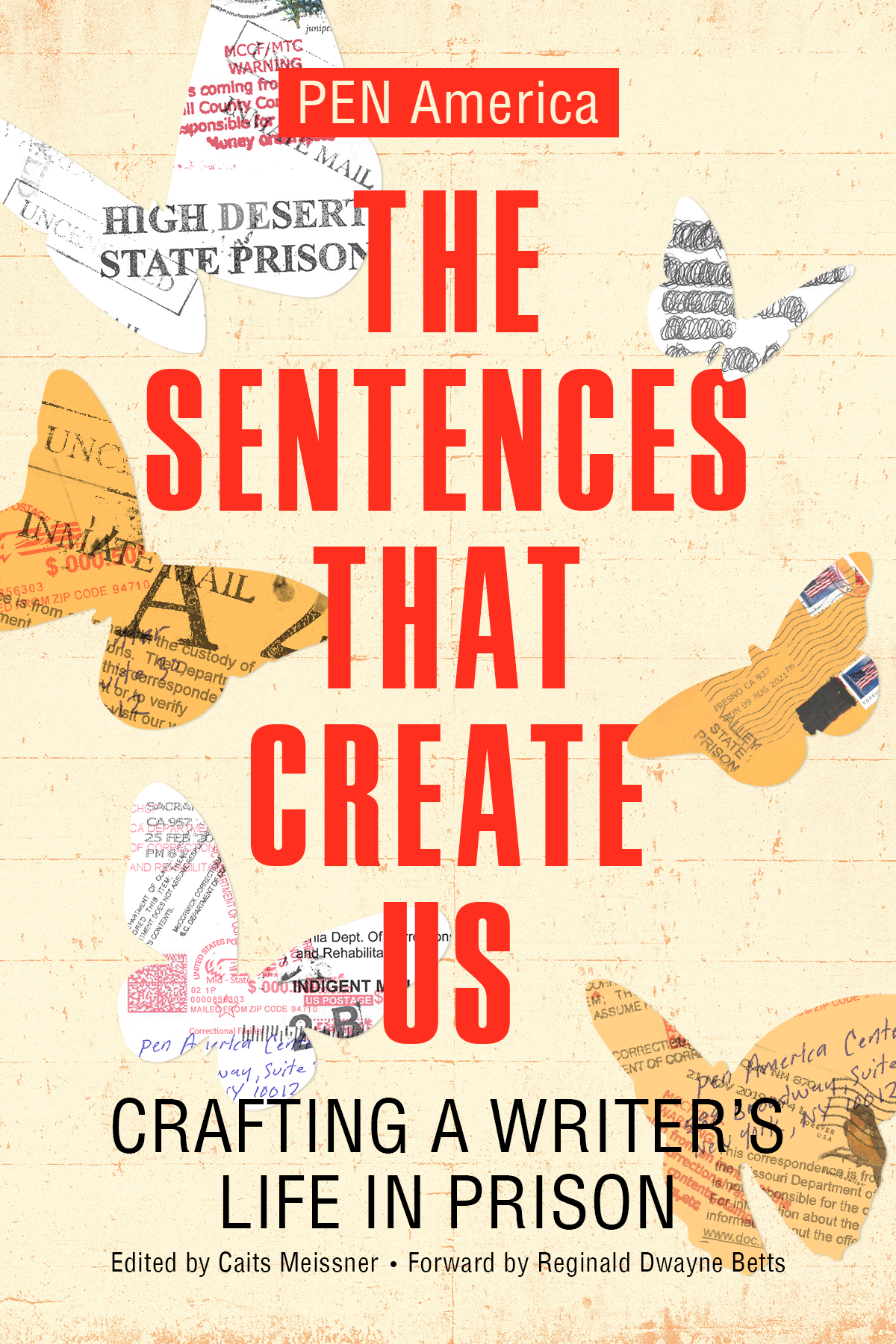

As the director of Prison and Justice Writing at PEN America, Caits Meissner receives a lot of mail from incarcerated and formerly incarcerated writers, both aspiring and established. Others are simply thinking of putting pen to paper and are seeking guidance. Meissner cannot read every piece of correspondence she receives, let alone respond to them. But together with a small team of eight, she works hard to lift up writings that need to be widely read — be they personal essays, reported pieces, poetry, dramatic works, or other forms of written expression. Because the need for guiding writers in prison is great, Meissner, in collaboration with her organization and Haymarket Books, edited The Sentences that Created Us: Crafting a Writer’s Life in Prison, which she describes as a collection from “writers who have broken boundaries, made the impossible real, and challenged every notion about who is in prison, what they are capable of, and why it benefits us on the outside to listen.”

In this narrative essay, as told to Cristian Farias on March 9 via Zoom, Meissner shares how the mail she reads has shaped her thinking around mass incarceration, names the challenges writers in prison face, and offers tips on how emerging voices on the inside might use the written word to challenge the harms of the penal system.

From a human lens, reading the work of incarcerated writers has been a profound journey. Often when people get to the level where they’re able to dictate their narrative onto the page, and do it in a way that has some mastery and craft involved, you’re interacting through words with people who’ve gone through a tremendous personal journey of self-transformation. So what I’ve learned is that people do and can change. What I’ve learned is that any one of us could have a moment where we snap or some circumstance that puts us in the way of being harmed and harming others.

I don’t want to say that this work has given me hope for humanity. But what it’s done is showed me that there are almost codified ways that we can learn from people who’ve been through these tremendously difficult life experiences, both as perpetrators and victims themselves. I’ve learned the kind of grit and resilience and humanity and personal accountability that it takes to write from this extreme environment — to be writing from the often extreme position of having done something really difficult. Incarceration is an extreme human condition.

Incarceration is an extreme human condition.

Incarceration is also an American story — with 2.3 million people incarcerated at any given time, plus parole and probation plus families that are affected plus communities. If you haven’t been touched by mass incarceration in this country, you’re one of the lucky few. At this point, incarceration is another American narrative that has so many different iterations, and it’s as multitudinous as any other identity. For that reason, there’s so much life to be found in the work that I read, that comes right through the pages. And as we know, a prison is a space that really likes to clamp down on life and life force, because life force, creative life force is very powerful.

PEN America, where I work, doesn’t take a position on the harms of American mass incarceration. Our mission is freedom of expression. But speaking as Caits, I believe we absolutely need to destroy the system and figure out ways to deal with harm. Since I was a 14-year-old kid, watching the Ella Baker Center video “Books Not Bars,” about youth incarceration in California, I already knew that the system was terrible. I understood the racial inequity, the class inequity, the myriad ways in which the system has worked to further repress Black and brown people in particular — but really, it harms everybody, regardless of race, class, and gender. It is a harmful system that perpetuates harm. I’ve felt its horrors, even if I haven’t directly experienced them, since I first visited Rikers Island in my 20s to teach a poetry class, and then went on to do the same at Bedford Hills, the only women’s prison in New York. Prison work has been the center of my life since then and has taken me to over 25 prisons and jails around the country.

And later, from reading these essays and books by people in prison, I’ve learned that the solutions are going to come from being in partnership with people on the inside. They are frontline reporters. They see and experience things that I can’t even stretch my imagination to envision, being in some of these highly abused positions, even having seen it with my own eyes in many ways. The people who know the most and have the most nuance are the folks who have experienced that day to day and who have the talents, skills, and grit to put that down on paper.

My hope is that the writings in The Sentences that Create Us give us a real investment into why prisons are not the answer — to really push us to start confronting some of these age-old questions of humanity: How do we deal with violence? How do we interrupt somebody’s path when it’s steeped in survival, and often results in crime? What kind of social services do we need? What are the interventions? What does restoration look like? These are the questions that the abolition community is really grappling with. I don’t believe we can change the current system; it will just become another version of the same. And I was on the fence about that for a long time. But after years of doing this work, I’ve become a lot clearer.

Prison degrades all of our humanity. And I’d like to see a world in which we develop solutions and prison becomes a term that we put up in museums, because now we’re studying our past.

There is one place in America that’s very dangerous to be a writer, and that’s prison. And in prison, there are layers. One is personal and the other is systemic. At the personal level, many writers in prison have a hard time believing they have any value or worth or ability to contribute to the conversation — or even to get to the point where they’re sitting in a prison cell, examining their past, thinking about the outside world, and what people think of them and their case after it’s been on TV or the newspaper or wherever it’s lived. The very first obstacle is the idea that they can and should and are allowed to write about their circumstances. From a personal accountability perspective, just being reduced to a number and abused and living in a cage, just to even find the self-esteem to believe My words are worth it, is the very first battle.

Then there’s getting the work through the walls, and that’s where we run into where the system exerts its power. Everything that’s going in and out of prison is censored. What we often see is writers who are being put in solitary confinement for their work, especially if the prison believes that it may make them look bad in some regard. We see people losing their jobs because they’ve written about the mental health unit. And even though people are in prison, like many of us, our work gives our life purpose and value. That kind of job loss is something that’s a spirit killer behind the walls. We see mail not getting to people from us and from others to prison because it gets flagged by mailroom staff.

Prison officials love to use safety as a blanket term to not allow many things. That’s not to say that safety is not an issue — the whole environment is an unsafe environment. So it’s already created. But there’s a lot of loopholes and ways that that gets thrown around — safety — as a way to just make sure that prison stays opaque. So that what happens behind these walls stays there. No access.

It’s important for people who want to work with incarcerated writers to know that the comrades they’re working with are taking a major risk in order to contribute to the national dialogue through their writing. I never take for granted that when incarcerated folks say, Yes, I’m going to work with you on this, Caits, that they might not see another human for quite some time if the prison doesn’t like what they’ve published.

The first question a writer must ask themselves in prison is, Am I willing to put myself out there? You’re joining a legacy of freedom fighters, essentially, through your writing. But what that comes with is risk. It comes with the possibility of an audience looking your crime up. It comes with the possibility of the prison administration coming down on you. I don’t want to say this to scare people off; I think we really need you. But I also want to underscore that the position you take when you start to write about the system from the inside is one of a comrade in a larger movement. Something that I’m so excited about with the book is that people in prison see other people in prison who are doing what they want to do as part of a movement, even if you can’t see it. People in prison are always going to see what the press can’t see; none of us can see what people in prison see.

The first question a writer must ask themselves in prison is, Am I willing to put myself out there?

The second piece worth thinking about is professionalism. This comes from the powerful Wilbert Rideau, who believes deeply that writing gets people out of prison. And his advice in the book is actually his rule in his newsroom at the time when he was inside. That rule was, Don’t bring your personal agenda into this, because people will not believe your writing if they feel you are trying to get something out of it. And of course, everyone in prison is desperate to get out of prison. How could they not be? I think it must be a significant personal challenge, and a creative challenge, to really separate my survival and my desire from my serious work as a writer in the world.

There’s a great essay in the book by Vivian D. Nixon, who taught women in prison to write grievances, which are formal administrative petitions within the prison system. And through the grievance-writing process, she’s really laying out how you write a personal essay. These things are not dissimilar: When you think about writing a grievance — which often are thrown out, or they don’t go anywhere in the prison system — it sometimes can be just a symbol of personal agency. But the idea here is, you’re writing a grievance, you’re saying this was done to me, and this is what I want to happen because of it. And that’s the lens: Agency in telling your story, pointing to the problem that your story illuminates, and then working towards fixing it.

I can’t overstate the importance of making visible to incarcerated writers their peers who are getting published, because I think the sense for many is, Who wants to hear from me?What do I have to offer? And then you read somebody’s work who’s in your same condition, and it breaks open a whole world of possibility. Our book accomplishes that in a lot of ways. Naturally, there are those who do feel their voice matters but still face various barriers. Something we do on our mentor program, where we pair writers working through the walls with the writers on the inside, is sending in the work of other incarcerated writers that has been published in a high-level scale — and giving people a sense of what’s even available to them.

Image: Samuel Rios/Unsplash