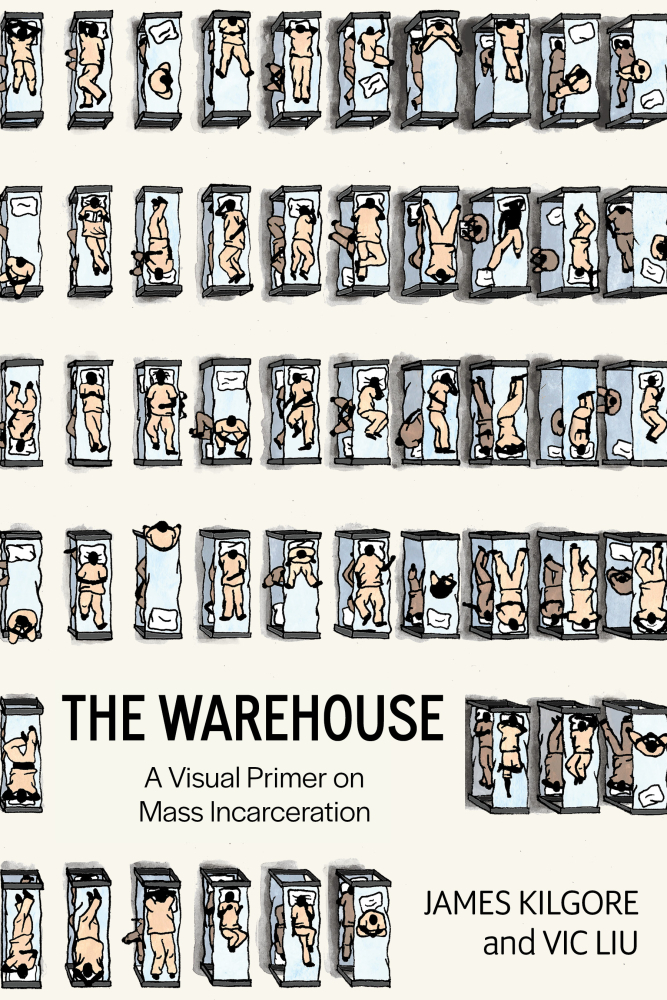

When artist Vic Liu first reached out to activist James Kilgore, it was to propose the idea of improving the graphic design of Kilgore’s award-winning book Understanding Mass Incarceration. Several years later, something much more complex and striking has come into being: The Warehouse: A Visual Primer on Mass Incarceration, out now from PM Press. The project, cowritten by Kilgore and Liu with design and art by Liu, is an art book that offers a kaleidoscopic introduction to the carceral state. The nimble text, paired with Liu’s careful design, allows for a work of striking compression, covering a remarkable range of topics despite its brevity. In the following interview with Liu and Kilgore, I talked with them about how the project came about, and how they see art playing a role in decarceral struggle.

—Adam McGee

Adam McGee: How did this project get started?

Vic Liu: I reached out to James because I read his book Understanding Mass Incarceration and thought that the graphic design—respectfully—could be better. I cold emailed him and was basically like: I want to make a visual version of this book and redesign it. What would you think about working together on this? And then it took three years to make it happen.

James Kilgore: It’s a credit to Vic’s imagination that she could see how to translate the previous book into this one. From my perspective, I could see the limitations of the book that I wrote before: not only was some of the information dated, but people read in a different way now than they did in 2015. I thought that adding in more visual elements could only expand the audience.

McGee: Vic, you’ve done an instructional art book before (Bang!: Masturbation for People of All Genders and Abilities) and clearly have a commitment to the power of art to teach people. When you read James’s book, were you thinking that adding art would deepen its instructional power?

Liu: Yes. If I were to have a thesis about my work right now, I think it comes from a place of finding text quite elitist. Text requires you to have a high comfort level in reading, and currently the average U.S. reading level is between seventh and eighth grade. This is not to say that people aren’t extremely smart, but it does point to a need to encase information about the world in a way that everyone can understand.

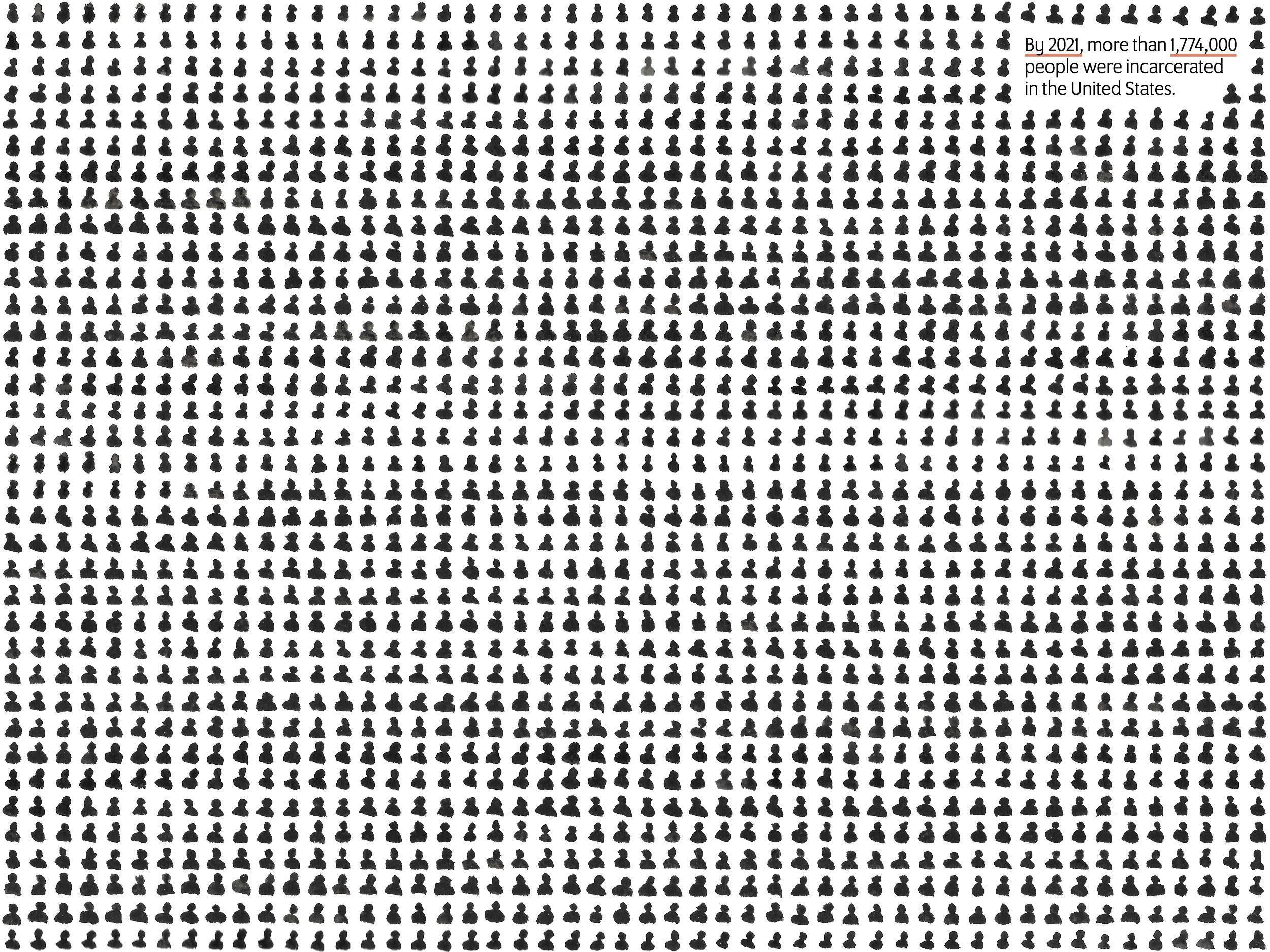

For me, art opens up a lot of possibilities in terms of intuition. I think that text is not intuitive. There are a lot of dimensions in art that allow you to communicate information on more of a gut level. For The Warehouse, for example, we have very few direct images of incarcerated people. That was entirely intentional. We don’t want you to just be staring at these people from a distance. We want to put you in their place so you understand the issues they’re going through.

Reading requires attention and energy, and people are burnt out and exhausted. We just went through a pandemic, we have to survive under capitalism—most people just don’t have the energy to read a big book that talks in unfamiliar language about a subject that’s excruciating to learn about.

Kilgore: I would second that. I wrote my previous book because when I was incarcerated, I was being sent books about prisons that nobody else on the yard could read because the text was so academic. When I wrote Understanding Mass Incarceration, I was writing with incarcerated people in mind as my intended audience, trying to create something that was readable by people of different reading levels. But, as Vic points out, even fairly accessible language and design still leaves out some people. So I’m hoping that this book extends the boundaries of who might engage with it.

McGee: With The Warehouse, you were building from the premise of James’s book. But it’s not just an illustrated version—it’s a new text. What was the process of developing the images and the text? Did the text come first, or the images?

Liu: Crucially, we did both at the same time. I really find the idea of having text on one page and a picture on the next page quite limiting. That automatically makes your brain go: Oh, this is just a depiction of the text. There’s a lot more potential when the elements are working together. You’ll find that some of the pages of The Warehouse are much more shaped by the text, and some of the pages are much more shaped by the images.

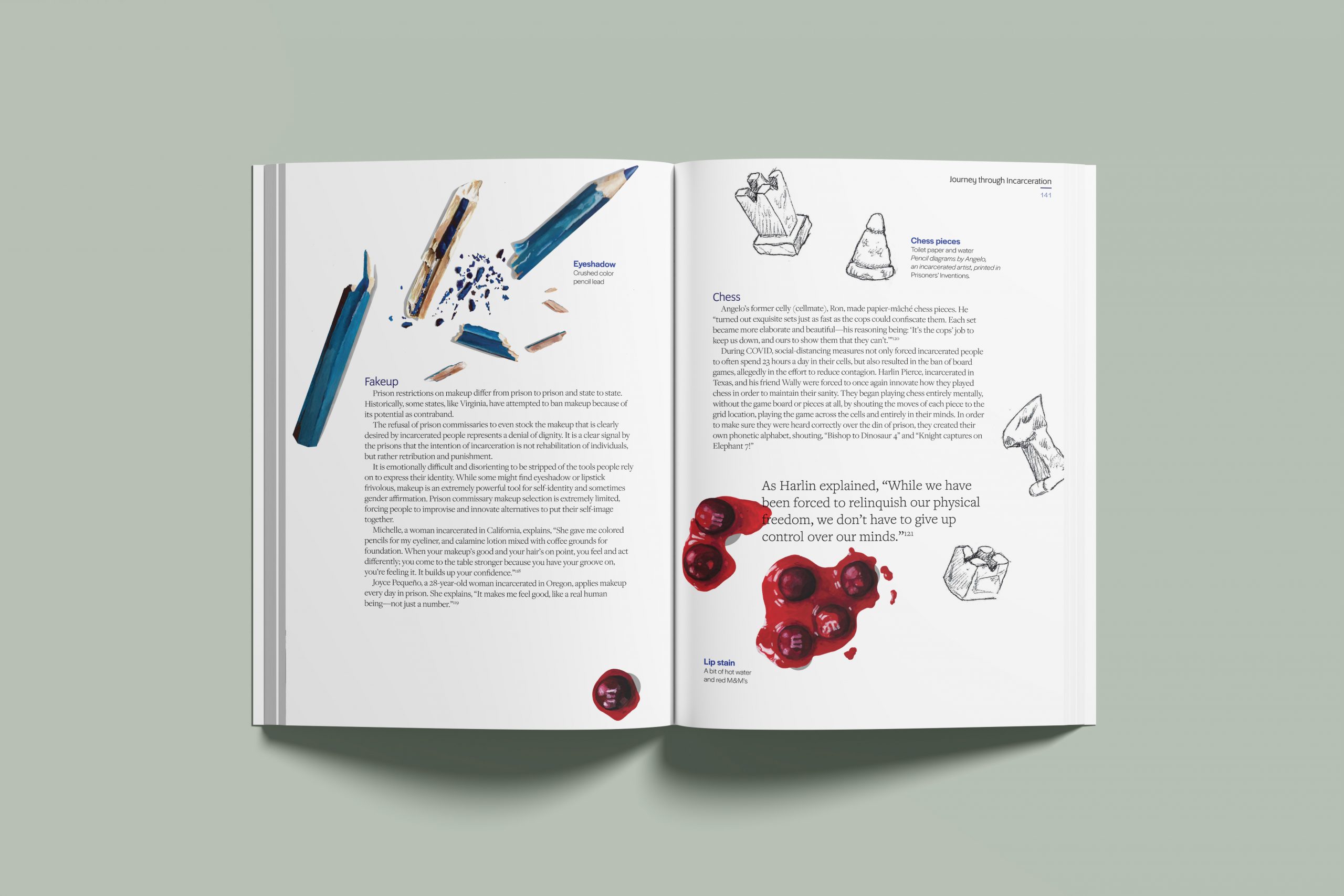

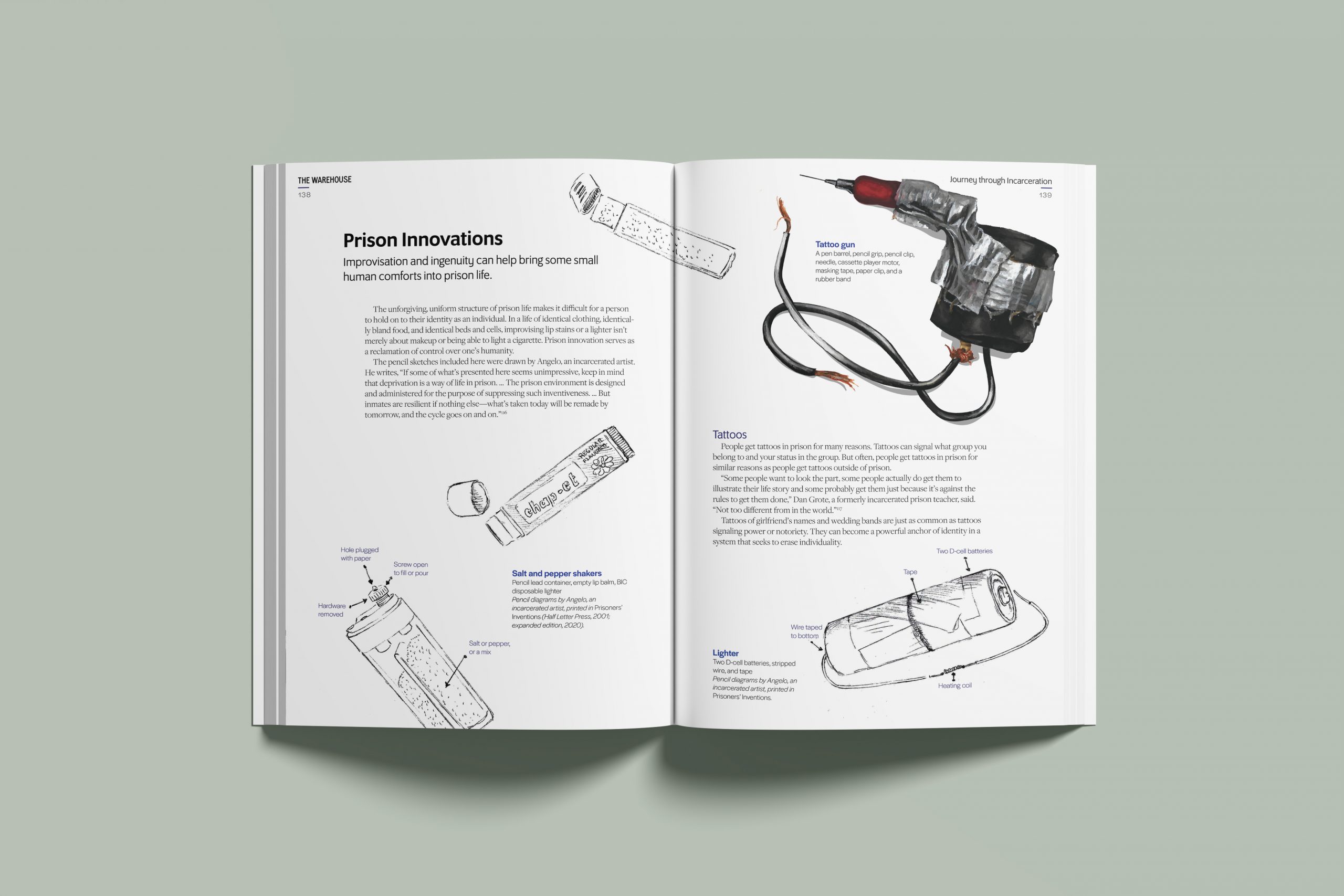

So sometimes James would write some sections and send me a rough draft, and then I would start playing with it, laying it out on the page. But, other times, if I had an image in mind or an illustration in mind, I would just go for it. A crucial part was that I wanted to stick to media, like illustration and painting, that are available inside of prison. I wanted you to be able to feel the human hand on every page.

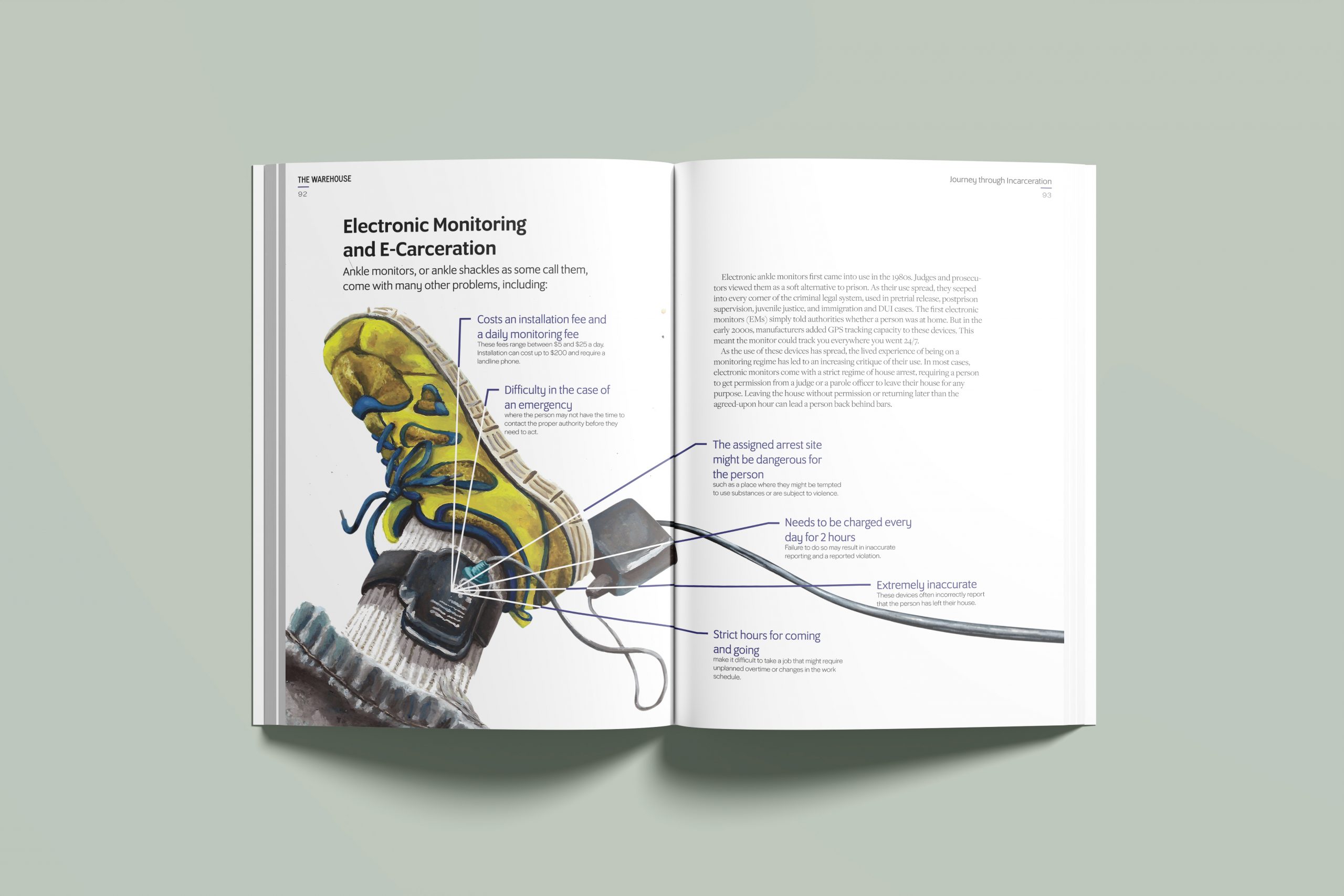

McGee: Reading the book, I was astonished by how many topics you covered, including many that are rarely discussed in texts aiming to give a survey introduction to mass incarceration. I’m thinking, for example, of the sections on prison tattooing, and how incarcerated people make their own makeup, and how glitchy ankle monitors are. Even still, I imagine that there were very difficult choices that had to be made about what to include. How did you decide what to address?

Liu: I think we probably have different answers to this. Making this book was very hard. It was emotionally quite taxing. A lot of that has to do with the tension between what mass incarceration does, which is dehumanize people, and what we want to convey, which is the humanness of those people. That’s a huge challenge: How do you communicate how incarcerated people succeed at reclaiming their humanity without downplaying the extent of the system’s dehumanization?

For nearly every image that we did end up including, I went through at least twenty other options. I don’t know if I always ended up choosing the correct one, but I certainly tried very hard. There are a lot of images that would speak to exactly how horrific mass incarceration is—but would also create distance between the reader and the person suffering. I also wanted to respect the fact that people will bring their own trauma to reading this, and I want them to be able to engage without being retraumatized.

Kilgore: One of the things that I really appreciated about the images that Vic chose and developed is that they had a lot to do with daily life inside prison, and that wasn’t the case in the first book. I wrote my PhD dissertation about domestic workers in colonial Africa and how, in their daily lives, they resisted the impositions of their employers. It’s the same thing in prison: people resist the rules. They find ways. They create makeup from what is available. They make wine. They smoke, they smuggle in drugs, they liberate stuff out of the kitchen and cook things in the microwave. I call these daily acts informal resistance.

The big prison labor strikes are also important, but you have all these other ways in which people resist oppression on a regular basis. In this book, we tried to capture some of that—and part of including that was wanting to create a book that has people who have been incarcerated in mind as readers. They’re going to be able to look at a page and say, “Yeah, that’s what we do,” with some element of pride. I think people who haven’t been incarcerated will learn from that cleverness as well. It’s really asking: How do you make something out of nothing?

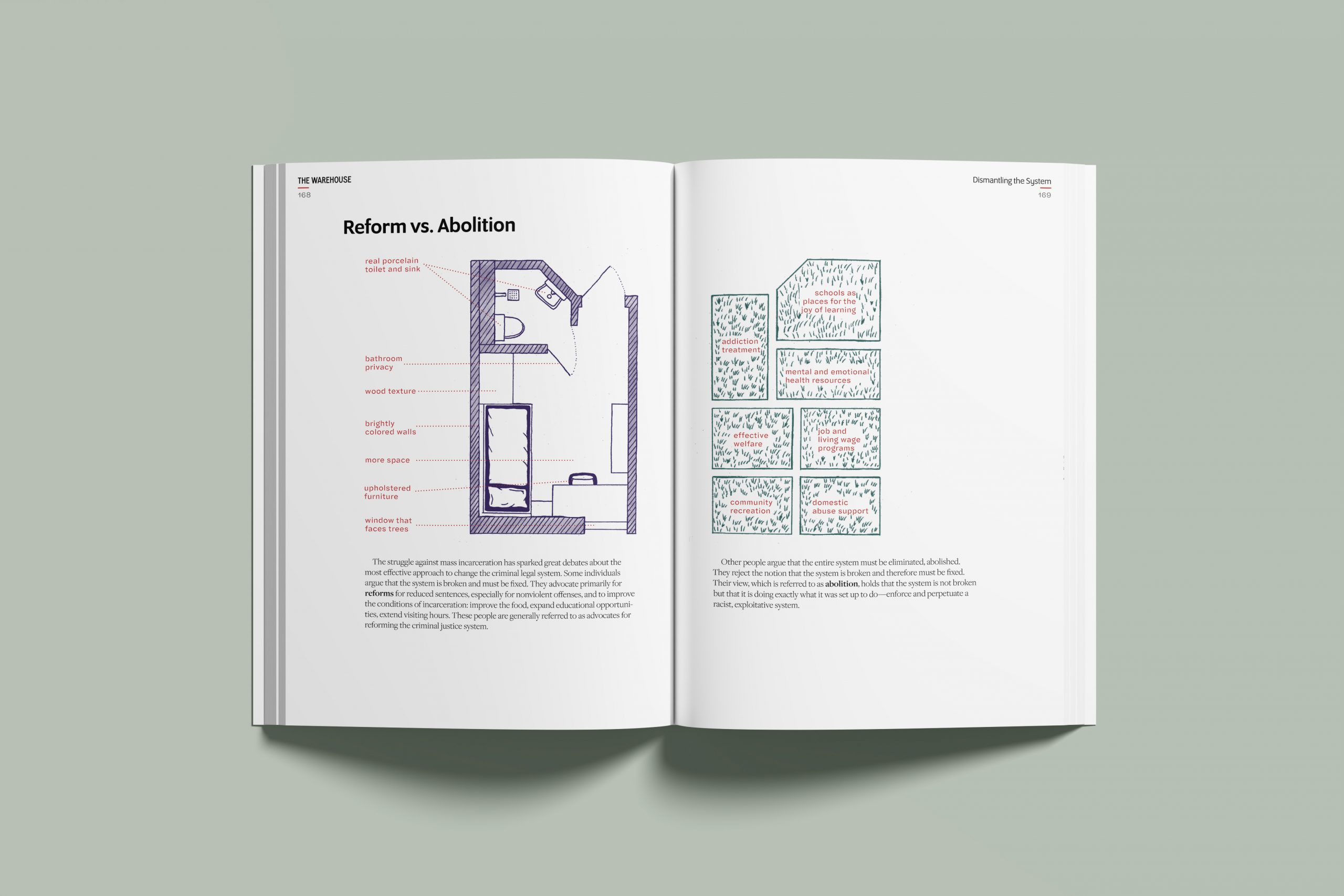

McGee: My favorite spread in the book is the one that shows the contrast between reform and abolition. On the left-hand page, there’s a drawing of a prison cell on which there are arrows pointing out all of the things that would be nice reforms—basically, to improve the living conditions of the cell. The facing page contains a shape that is the mirror image of the cell’s outline, but it’s broken up into all these smaller boxes that describe what it would take to transform society to actually end our dependence on incarceration. For me, this did the thing that art is uniquely capable of, which is offering a totally new way to see something.

Liu: I’m so glad you liked that spread. I’m not supposed to say this, but I felt very clever after designing that one.

McGee: It’s really great. I would love to hear if you have favorite pages or spreads.

Liu: I would say the portraits that we commissioned from incarcerated people. Those are really, really important to me. I think that the book would feel a lot more empty without them. They bring a lot of heart, and the diversity of voices is so palpable from just seeing the different hands behind them. James, what about you?

Kilgore: Well, I like that abolition spread that you mentioned, Adam. As you said, it kind of captured it all in two pages. I feel like you can have a long discussion about that particular spread. I also love a lot of the images that show the scale of mass incarceration; those are really powerful. And Vic’s drawings are amazing at capturing the details of technologies and hacks that incarcerated people develop themselves to make life inside livable. Those things rarely appear in photos, or when they do, seem a little bit sterile.

McGee: There are things art can do that straightforward documentary photography can’t always capture. Art can conjure possibilities that didn’t seem to exist before. On that note, having created a sort of art book about mass incarceration, I’d love to hear your thoughts about the political potential of art, and what role you think it can play in progressive movements.

Liu: I am currently in a very difficult relationship with art. I think that a lot of people have complex feelings about art that ends up in museums, understandably, because in the circles where you can survive as an artist comfortably, art is a vessel for money. But I do think that at its highest potential, art has the ability to capture something about the human condition, whether that’s written or visual art. Art is a way of having conversations about things that are important to us. That is where art has the potential to further social change, because it connects us. We would be so much more lonely in a world without art.

Kilgore: I’m going to take things in a bit of a different direction. Back in the prison cell blocks, I was surrounded by art. Dozens and dozens of people are creating different things with the limited resources that they have. You’ll see guys who have taken all the threads out of their sheets, boxer shorts, and pillowcases and they’ll be weaving those into something. You’ll find people taking potato chip bags and making them into picture frames or purses and sending them home. And then you find dozens of people creating cards and portraits of their family members or family members of other people there. All of this is happening on a constant basis.

Decarceral thinkers and doers

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

When I first landed in prison, that was in South Africa. Within a week, one of the guys there had made portraits of all my family members, which I was able to give to them. I’m not a visual person, but for me, the art of writing is really what kept me connected to my communities after being extradited to the United States. I had no way to regularly connect with my family back in Zimbabwe and South Africa. So I wrote. I wrote stories; I wrote novels that dealt with that scenario. I made lists of the smells and sounds of the community where I lived and incorporated those into my fiction. Those were real emotional connections.

People don’t really talk about prisons as a hotbed of art, even as the people there are making art all the time. People can make a cheesecake out of ingredients liberated from the kitchen, and it becomes a work of art. It also then becomes a commodity. People create these things and then sell them, and it creates a whole informal barter economy. Creativity is inspiring and builds pride but also is a source of income. So I think art plays a really important role for people who are incarcerated. It allows people to take their skills and make something out of nothing.

Header image: “By 2021, more than 1,774,000 people were incarcerated in the United States,” a spread from The Warehouse, used with permission of the authors.