As in prior years, the books that moved us in 2024 were as varied as our contributors. Some of them were written by people who have experienced incarceration. Other authors have fought against the system as organizers or advocates working on specific campaigns. Some have dedicated their lives to studying or documenting the harms of policing and prisons, and what communities are doing about them. And yet others work directly with those communities to create meaningful, alternative forms of public safety.

Our staff picks, which are by no means exhaustive, reflect the kind of work that inspires us regularly—and that we are pleased to continue publishing as we head into the new year. The challenges ahead for those of us who believe in a world without mass incarceration are daunting—but we still believe a decarceral future is possible if we remain committed to it.

Premal Dharia, James Forman, Jr., & Maria Hawilo (editors), Dismantling Mass Incarceration: A Handbook for Change (Farrar, Straus & Giroux)

There are so many different institutions that sustain mass incarceration, each with its own incentives and political logics, each with its own promises of reform, and each with its ethical morasses that threaten to bog down organizers. Dismantling Mass Incarceration tackles that many-headed hydra all at once. This collection of fifty-five writings and essays is organized into sections that are each devoted to a particular player: prosecutors, police, judges, prisons, and public defenders—the final choice standing out for its focus on a topic that’s often kept in the background but will be of interest to many readers. The essays explore what has been done and could be done, and they’re at their best when they surface tough strategic questions: lessons to draw from seeming failures, and pitfalls of seeming successes. Taken individually, the chapters are an easy entry point for someone just learning about these issues. Taken together, the book offers a guide for those who want to rekindle their imagination about all the paths their activism could take. [For our forum on progressive prosecutors inspired by the book, click here.]

—Daniel Nichanian, contributing editor

Max Felker-Kantor, DARE to Say No: Policing and the War on Drugs in Schools (University of North Carolina Press)

I don’t have many vivid memories from my childhood. One of the few is of being in elementary school and stumbling upon our DARE officer—Officer Dan—leaning against the brick wall of our school, smoking. The timing made it a doubly infelicitous discovery: Officer Dan had only just completed teaching a unit about the harms of smoking. It was, for me, a formative moment of realizing that adults often say one thing while doing something else, and—as much as my tiny brain could parse the lesson—a dawning awareness that one should approach the powerful from a position of skepticism. No surprise, then, that I was eager to read Max Felker-Kantor’s deeply researched DARE to Say No: Policing and the War on Drugs in Schools. The book uncovers how DARE was a carceral state effort to create a soft-power, cultural front that would advance its work of selling mass incarceration and the war on drugs. As Felker-Kantor shows, DARE sought to create a generation of snitches, baby police in every home. The extended hope was that we’d grow up to be voters who would embrace policing, in all its violent excesses, as a beloved defender of our communities. [To read our preview essay for the book, click here.]

—Adam McGee, managing editor

Rachel Herzing & Justin Piché, How to Abolish Prisons: Lessons from the Movement Against Imprisonment (Haymarket Books)

Nelson Mandela famously said that the work of upending monumentally entrenched systems of injustice “always seems impossible until it is done.” Inspiring as those words are, the quote’s retrospective cast can be perplexing: “It is done,” Mandela says, and in the light of its being done, we can see that what seems impossible actually is not. But of course, the daunting work of upending monumental injustice—like the monumental injustice of the U.S. penal system—feels most impossible precisely when the history of whether it has been done is not yet written. In that essential interregnum, when hopeful action draws needed strength from concrete inspiration, we are encouraged most not by evidence that the impossible has been done, but by reminders that the work to accomplish the impossible is in fact being done, with important progress, in the here and now. Incomplete, interstitial, and interrupted progress, to be sure, but forward moving all the same. In How to Abolish Prisons, Rachel Herzing and Justin Piché give us this inspiration and more, in a self-described “love letter to the people and organizations” doing the work of abolition today. Describing the campaigns, communities, and collectives driving that work forward, Herzing and Piché show, as they write, that a world without the harms of mass incarceration is not just a “beautiful vision of the future,” but a concrete practicality being constructed in our midst, by committed organizers fighting tirelessly to “enhance our collective well-being and ability to respond to harm.” [For our interview with Herzing and Piché, click here.]

—Andrew Manuel Crespo, coeditor-in-chief

Raj Jayadev, Protect Your People: How Ordinary Families Are Using Participatory Defense to Challenge Mass Incarceration (The New Press)

Law school textbooks are filled with court opinions, the words of judges declaring how laws should be interpreted, one winning side at a time. And lawyering often involves reading those opinions and trying to make your side the winner. This cycle continues, as does the illusion that these wins are the central means by which justice is delivered. As a lawyer and former public defender, this cycle is very familiar to me—it’s one I have participated in for years. And, indeed, there can be justice found in those wins—such as the intrinsic justice in a person being freed from the carceral system’s grip. But as Raj Jayadev describes in Protect Your People, the growth of participatory defense is pushing public defense in new, important directions. Participatory defense seeks those wins, but does so while never losing sight that all of this is ultimately about people—and, powerfully, about the collective power of communities learning, teaching, pushing, organizing, and fighting for their people. Pushed by participatory defense organizers, “public defenders could be a weapon of the movement rather than an apparatus of the carceral system.” In our system of mass incarceration, public defense is undeniably crucial. And as it barrels forward, trying to keep up with and push back on the state’s relentlessly punishing infrastructure, this intervention by organizers is invaluable. Instead of feeding the system by offering a service to its targets, it builds the power of the very communities targeted by the system to fundamentally challenge it. [For our excerpt from the book, click here.]

—Premal Dharia, coeditor-in-chief

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

Andrew Krinks, White Property, Black Trespass: Racial Capitalism and the Religious Function of Mass Criminalization (NYU Press)

Raised Catholic, I’ve always been interested in how adherence to religious principles shapes a person’s engagement with those around them—both positively and negatively—well beyond the context of a church or faith community. In White Property, Black Trespass: Racial Capitalism and the Religious Function of Mass Criminalization, Andrew Krinks extends this to a societal scale, using religion as a critical lens to examine how European, Christian ideals have underpinned carceral politics and sanctified whiteness, property, and police power. Krinks argues that the criminal legal system operates as a pseudo-religious order, enforcing racial and economic hierarchies while presenting itself as a force of salvation. At the same time, he challenges the idea of faith as merely a means for control, instead emphasizing the religious nature of abolition and how its spiritual and transformative practices empower us to resist and dismantle oppressive systems. [For our excerpt from the book, click here.]

—Daven McQueen, assistant editor

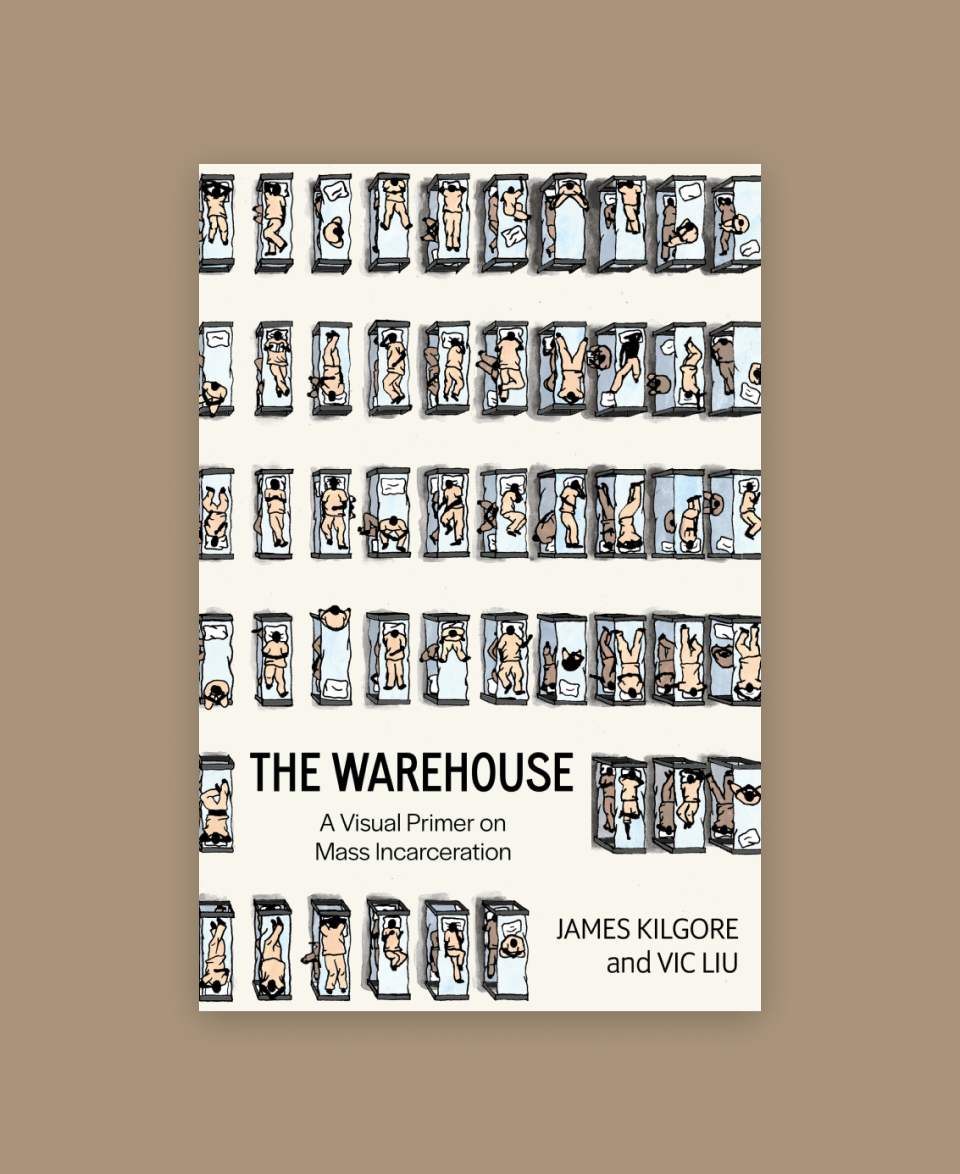

James Kilgore & Vic Liu, The Warehouse: A Visual Primer on Mass Incarceration (PM Press)

For the millions who experience them daily, the harms of mass incarceration are visceral, palpable, sensory, corporeal. Prisons aren’t good at very many things, but one thing they do well is keep these indignities—which the United States inflicts on its own on a scale unrivaled in the world—hidden from public view. Equal parts art book and illustrated guide, The Warehouse: A Visual Primer on Mass Incarceration is first and foremost a public service in that it forces us to not look away from these realities and the humans who live them—without glamorizing or minimizing any of the system’s horrors. In the best tradition of zines and other resources that educate and move people to action, this collaboration between James Kilgore and Vic Liu doesn’t simply inform, but also encourages us to imagine a different world. And, with that, what people in and out of prison are doing to build it. Indeed, as I read and appreciated this work, accessible and striking at once, I couldn’t help but imagine it, in a not-so-distant future, turned into an exhibition in a museum: not as a showpiece to boast about, but as an enduring reminder of a human tragedy, like chattel slavery and internment camps, that has no place in our shared reality. [For our interview with Kilgore and Liu, click here.]

—Cristian Farias, senior editor

Laura McTighe & Women With a Vision, Fire Dreams: Making Black Feminist Liberation in the South (Duke University Press)

Fire Dreams: Making Black Feminist Liberation in the South is about what it takes to keep going when everything around you tries to make you stop. Laura McTighe and Women With a Vision (WWAV) trace the history of this Black feminist collective in New Orleans—from their early days fighting the HIV/AIDS crisis in the 1980s to their work today on reproductive justice, harm reduction, and abolition feminism. But this isn’t just a highlight reel of victories. The book takes an honest look at the setbacks—like the 2012 arson attack that nearly destroyed WWAV—and what movements do in those moments of loss to persevere. It’s a refreshing, realistic approach that shows how hope isn’t abstract: it’s built in the relationships and care that sustain organizing through its hardest moments. WWAV’s story feels like a blueprint for how movements survive and thrive, rooted in the legacy of southern Black women’s community leadership and the worlds they keep creating, even in the ashes. [For our excerpt from the book, click here.]

—Daven McQueen, assistant editor

Michelle S. Phelps, The Minneapolis Reckoning: Race, Violence, and the Politics of Policing in America (Princeton University Press)

It is tempting to look back on the summer of 2020 and lament. For those few heady months, the way forward seemed so clear, as a swelling popular protest movement looked destined to bring a reluctant United States into a new era. Michelle Phelps’s Minneapolis Reckoning is an account of that long, difficult struggle to transform policing in the City of Lakes. Phelps resists the tremendous appeal of a simple elegy while paying careful attention to the many forces that have long constrained anti-police activists. What emerges from her study is an account of the limited, but nevertheless real, choices faced by those living in one of many over-policed and under-resourced communities in the United States. “I don’t have faith in [police] at all,” one Black woman tells Phelps. “But then at the same time, you gotta call them if you need ’em. . . . You damned if you do, you damned if you don’t.” Phelps does not settle for easy explanations, but makes a strong case for the possibilities—and perhaps even necessity—of dwelling in the here-and-now of anti-police activism, where those wishing for a new world must relate to 2020 as a practical resource rather than as a revolutionary reverie. [For our excerpt from the book, click here.]

—Daniel Fernandez, consulting editor

Jessica Pishko, The Highest Law in the Land: How the Unchecked Power of Sheriffs Threatens Democracy (Dutton)

The right-wing rallies at the heart of The Highest Law in the Land seem like another universe. Pishko sheds light on the people who serve as sheriffs, the ideologies that animate them, and the stories they tell about themselves. Spoiler alert: it’s a scary book. The sheriffs in this book often act like they’re above the law. Or rather, they say that they are the law—and, in a certain way, they’re right. Throughout history, sheriffs have been implicated in “some of the worst crimes of the criminal legal and policing system,” including administering convict leasing, running jails where death and disease were rampant, and, time and again, violently restricting Black Americans’ attempts to exercise their rights. Yet the office of the county sheriff still exists, a vestige of a bygone era that continues to arrest, incarcerate, deport, and kill people in the present day. The badge of the county sheriff still blesses the whims of a white man with a gun, and for this reason, the far right loves sheriffs and many sheriffs love the far right. Understanding the culture, legal status, and future of sheriffs in the United States is immensely useful to a reader wondering what may be in store for criminal legal reform and abolition in the next four years. These are big questions, and Pishko’s deep dive into sheriffs helps to answer them. [For our excerpt from the book, click here.]

—Avery Farmer, audience development assistant

Andrew Ross, Tommaso Bardelli & Aiyuba Thomas, Abolition Labor: The Fight to End Prison Slavery (OR Books)

If you, like me, wondered how voters this election could have rejected California’s Prop 6—a ballot measure to end forced prison labor that supporters dubbed the “End Slavery” act—Abolition Labor is for you. But more, this rich account of the origins and evolution of prison slavery, and the ongoing fight to “end the exception” to the Thirteenth Amendment, is for anyone who cares about prison conditions, labor rights, and what it means to participate in a capitalist economy facilitated by the labor of people in cages. In reading it, I was most struck by the interviews with currently and formerly incarcerated workers. Andrew Ross, Tommaso Bardelli, and Aiyuba Thomas weave vivid stories from these workers throughout the book—like Donna, whom Texas forced to pull weeds in the 104-degree heat while on her period with no bathroom access. These compelling stories helped me ground my understanding of prison slavery in the violent realities experienced by those inside. This book will tune you in to legislative and other campaigns around the country pushing to change these realities and avoid the same fate as California’s. [For our related essay from Ross, Bardelli, & Thomas, click here.]

—Corinne Shanahan, student attorney, Institute to End Mass Incarceration

Katie Tastrom, A People’s Guide to Abolition and Disability Justice (PM Press)

Katie Tastrom’s A People’s Guide to Abolition and Disability Justice makes a compelling case for allied liberation movements. It is not simply that abolition and disability justice both possess a vision for full, inclusive freedom; in many cases their aim is to protect the exact same people. Prisons not only worsen existing disabilities but also generate new ones. Moreover, disabled people—particularly disabled people of color—are more likely to be victims of police violence: Eric Garner and Freddie Gray, for example, both had diagnosed disabilities when they were killed by police. Disabled people are also more likely to end up working in criminalized sectors of the economy (such as sex work), and are more likely to end up in a carceral setting, whether that’s a literal prison or the locked ward of a hospital or care home. Tastrom’s book offers a thorough primer on all of these issues, and seasoned activists will be moved by its call to more thoroughly incorporate a disability justice perspective into abolitionist struggle, and vice versa. [For our excerpt from the book, click here.]

—Adam McGee, managing editor

Image: Heather Newsom/Unsplash