When he wrote his memoir, Bird, Uncaged: An Abolitionist’s Freedom Song, the last thing Marlon Peterson wanted to do was to write a prison book. Instead, he wanted to reflect on how his experiences on the inside were manifestations of things happening on the outside. After spending 10 years, two months, and seven days incarcerated, Peterson has dedicated himself to writing, creating programming, lecturing, organizing, and advocating alongside the formerly incarcerated, victims of gun violence, women, immigrants, and young people. Marlon is the host of the Decarcerated podcast and the owner of a social-impact endeavor, The Precedential Group Social Enterprises. His TED talk, “Am I not human? A call for criminal justice reform,” has garnered more than 1.2 million views. On August 19, 2021, he spoke to Inquest via Zoom, and his words, as told to Premal Dharia, have been edited and condensed for clarity.

I would often say that I knew how I got to prison very quickly. And it wasn’t the crime necessarily that I was arrested for; it was for this path of choices I started making that began with certain traumatic incidents that I had early in my life, throughout my teenage life. And I’m not absolving myself from what I was a part of but, just to say, “Wow, these things led to that decision, and that led to this, and I wouldn’t have been around there if that didn’t happen.” And connecting these dots. Now, we tend not to connect these dots in real time. But I had hindsight, and we all do — hindsight is 20-20 so we can see these things.

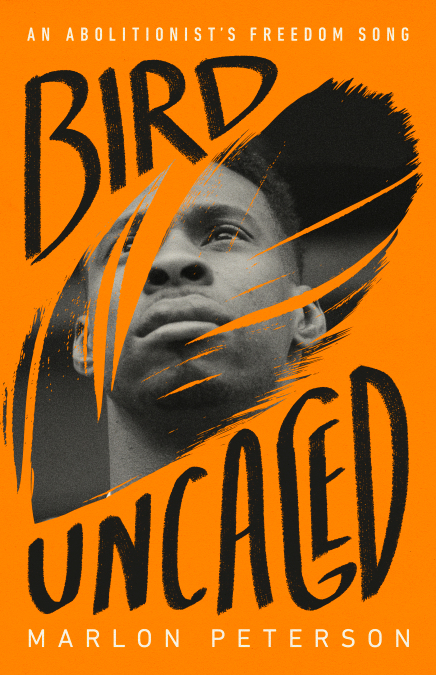

The title of my recent book is Bird, Uncaged: An Abolitionist’s Freedom Song, and the latter half of the title of the book didn’t come about until the book was written. I point out to folks that you don’t even see the word “abolition” in the book until the very last few pages. I didn’t set out to write an abolitionist memoir. The journey of writing led it there. Now, I’m not saying I discovered abolition through the process of writing this book. I’ve been talking about abolition and writing about it for a while now. But for me, I went through these various types of things as a perpetrator and as a person who has been harmed. And I was like, “Wait. The thing that I’ve gotten to, the politics that I’ve been speaking about, reading about, learning about over the years — abolition is where all of that leads me.

The reason why I didn’t want to write a prison book is that I realized that the issues happening in prison are happening on the outside, too. We need to look at all of those things — the root of all of those things.

I knew I was writing a memoir and I knew I didn’t want to write a book just about me being incarcerated. The reason why I didn’t want to write a prison book is that I realized that the issues happening in prison are happening on the outside, too. We need to look at all of those things — the root of all of those things. That, to me, is the politics of abolition.

I recall how in New York state — definitely now, but more so in the 1990s and early 2000s and even early 2010s — people would not get released on parole. Even though that wasn’t my situation, I worked with men on the inside who were dealing with many, many parole denials of release. And it was arbitrary and capricious and vindictive and all the things. In so many ways that was my introduction to the politicization of incarceration. All these men around me who are wonderful guys have been in jail 20 or 30 years and haven’t done a thing wrong in most of that time. And they’re still getting denied parole. It was political. I really understood then the politicization of these individuals’ freedom.

I’ve realized that there’s an infusion of the macro into our lives. We don’t live in a vacuum. There may be certain idiosyncrasies to the neighborhood, but this is not just about Crown Heights or Bed Stuy in Brooklyn or Jackson, Mississippi or wherever. It’s a larger context. For me it’s always important to home in on the interpersonal, but don’t leave out how systems and policies are impacting that. Because when you do that, you’re leaving the people who are being directly impacted on this island of Why don’t you just get it together? That’s how our criminal system has worked: Why don’t y’all just get it together? These people did! And that’s incorrect. It’s a harmful way of looking at policy.

A good amount of my work has been around gun violence and gun violence prevention — at least post-incarceration. I’ve worked with people who have been shot. People who have shot. I’ve been in the hospital, in family’s homes, in funeral homes, on streets. I’ve been around all sides of that. And I realize that, as I’ve connected my dots, I’m seeing people illustrate these dots in front of me. But our criminal system isn’t set up that way. It’s not operationalized that way. Of course we’ve got individuals, institutes, and nonprofits — we’ve got all sorts of people that try to interject and interrupt it. But operationally, it doesn’t work that way. It doesn’t work to care about why you’re making those decisions. For me, it’s just super important that we investigate the truth and the entire biography of people.

We need to talk to the people who have been harmed. And to the people who have done harm. Talk to them! Talk to people we’re scared of. They can tell us. We have to talk to the people. The way that we figure this out is by talking to us — understanding who we are in totality. Understanding that that man who committed a nonviolent crime is not more of a person than the person who committed a violent crime.

Think about who ends up in abusive relationships. Or those who end up in relationships where they feel like they’re never emotionally cared for. They find themselves in these situations and these types of relationships over and over again. There’s often a parent issue. Or somebody didn’t show them attention or love. Or they were abusive to them. Or they weren’t given enough love or affection or touch, so they keep seeking this sort of thing from other people, not realizing that they need to create these sorts of things internally. A lot of these things are internal to how you feel about yourself and your own self-esteem and security. So when you think about people in the carceral space, it’s no different. We aren’t creatures from another planet. You know what I’m saying? We are everybody’s brother, sister, cousin, father, mother — what have you. So, we also are, in so many ways, informed by experiences that were harmful or hurt us or confused us or left us feeling empty. You have all of these people and all of these experiences and then you have all of these opportunities for social deviance.

Just think about weapons: We just happen to live in a society where there are more guns than there are people! People are funneled into the system — whether it be through the foster care system, whether it be through the school-to-prison pipeline. The school-to-prison pipeline — it’s not just that they have security guards and police and metal detectors in the school that helps prepare people for prison, or desensitize people to that type of overreach of the law. But teachers also miss things that are happening to the kids. And when you miss it, and the kids are looking for it, they find ways, they find friendships, they find community, they find other ways. They find mental health — even if it’s a façade — they find mental health support: weed, drugs, sex, gangs, robbing, stealing. All of these things gives them a sense of belonging, of escape.

So when we think about the criminal system, it’s not operationalized to be able to understand those things or how to deal with those sorts of things. The emotional pains that so many end up with. And I want to be clear: I’m not saying you have to be mentally ill to go to prison. But I am saying that the scope of mental instability doesn’t only reside in the DSM.

The reason I use the term operationalize is because I have a degree in organizational behavior, so part of my mind just works that way. I’m just thinking about the system as a machine. It is a machine, and everybody is trying to interrupt it in various ways — throw a little cog, throw a little wrench in there. But it’s a machine and it’s moving, you know? And that’s what we do to bodies. No matter what the men or women or other people inside of these places think or say — not only does the system think they should be censored, but their ability to even critique the system while they’re here just shouldn’t happen. That’s an interruption to the system that it doesn’t want because it doesn’t want more people thinking they can critique it, especially from inside.

Anytime you go and transfer from one prison to the other, and I’ve been transferred, you’re cuffed however you’re cuffed — ankle to the neck to the hip, maybe. And they always refer to you as bodies. “We have 35 bodies on this bus.” “We have 25 bodies on this bus.” And you’re hearing it! You’re there. You’re right there, and they’re just saying “bodies.” “How many bodies?” They can’t keep count of how many of us are going through the system every day, every week, every month, every year. So it’s moving on its own. It’s an engine of humans! That’s why slavery — chattel slavery worked for so long because it didn’t matter if his name or her name was such-and-such. Or if he had an illness or she had dementia or they had heart problems. It didn’t matter! It was just, We just gotta keep this thing going. And if you step out of line, there’s a discipline for that because we gotta keep this system going. It’s no different from the operationalization I mentioned. I think it’s important for us to realize that we are either working within a machine, or we’re working to interrupt or demolish this machine. It’s humbling to look at this machine that has been working for a long time, because obviously one person can’t do it. One organization can’t do it.

I think it’s important for us to realize that we are either working within a machine, or we’re working to interrupt or demolish this machine.

There are signs right before us that we need to be undoing this idea of what we think America is. Actually, not so much what we think America is — we need to undo what America is and create a community and a society that is much more loyal to the ideals of freedom and justice and liberty.

When we approach this work we have to think about not only how we can impact hearts and minds — a lot of my work is about hearts and minds — but also how we can create what I call a disruptive innovation. It’s a business term, disruptive innovation. I think I got it from the Harvard Business Review years ago. I’ll give you an example of what disruptive innovation is: the best one is Blockbuster Video and Netflix. Once upon a time you could go to any video store and rent your videos. And then someone came along and said, “Hey, you can see all these movies, but you don’t even have to have a physical tape. You can do it from your house. You don’t even have to leave.” And what that did was, it didn’t say, “Look, we’re gonna take Blockbuster and VHS out of business.” But it did say, “We created a new thing. We created this whole new thing. And now, you can stay with the old thing, but you should know that this new thing is more convenient. It’s better.” That’s how we need to be thinking about this work because that’s a systemic shift. Nowadays, there are no Blockbuster Videos, right? Nobody uses VHS anymore. We’re all on Netflix and Hulu and all the different platforms. We don’t feel bad that there’s no longer Blockbuster Video — maybe there’s some nostalgia or something like that. But we don’t feel bad about that. We created a whole new engine, an entire economy around this new disruptive innovation. When we think about this work, we have to think about it in those operational terms. How do we create disruptive innovations that just make it no longer necessary or possible for this arcane, inhuman system to exist?