During his 2020 campaign, President Joe Biden pledged to reform the criminal justice system and reduce mass incarceration. As he announced his top nominees to the Department of Justice, he promised to restore its integrity, independence, and commitment to equal justice under the law. But more than six months into Biden’s presidency, a top department role — one that shapes criminal law before the highest court in the land — remains empty. If President Biden is serious about reform, he must first reckon with how the solicitor general of the United States, the federal government’s top appellate litigator, has historically been a pro-prosecution friend to the Supreme Court — and hope that the person he has chosen for the role, Elizabeth Prelogar, will depart from that practice.

The Office of the Solicitor General is little-discussed outside of elite appellate circles, but its influence is enormous in criminal matters. The office exerts that influence not only in cases brought by federal prosecutors, but also in many cases that percolate up to the Supreme Court through state courts — that is, cases where the federal government isn’t even a party to the dispute. And that is because the solicitor general wields singular sway by jumping into cases as an amicus curiae — literally, as a “friend” of the court — by filing an amicus brief and seeking permission to argue. Anyone can file an amicus brief at the court, but the justices must affirmatively permit a non-party litigant to argue in a case. As we document in a recent article in the Vanderbilt Law Review, the justices grant that privilege almost exclusively to the solicitor general. Expert Supreme Court litigators we interviewed for that piece told us repeatedly that they believed that the traditional conception of the solicitor general as the Supreme Court’s “tenth justice” was one of the main reasons the court permits the solicitor general to argue as an amicus so frequently.

Our qualitative and quantitative review of the solicitor general’s amicus positions in our article revealed that the solicitor general has increasingly used that discretion to enter politically charged cases on the side that reflects the president’s ideology. The solicitor general enters many high-profile cases on issues like abortion, affirmative action, and civil rights in order to advocate for the position favored by the president who appointed him or her. There is one category of cases, however, in which the solicitor general almost always seeks to participate and does so on the same side, regardless of the administration and even though the federal government’s interest is minimal: The office routinely supports efforts by state and local governments to expand their coercive power over criminal defendants.

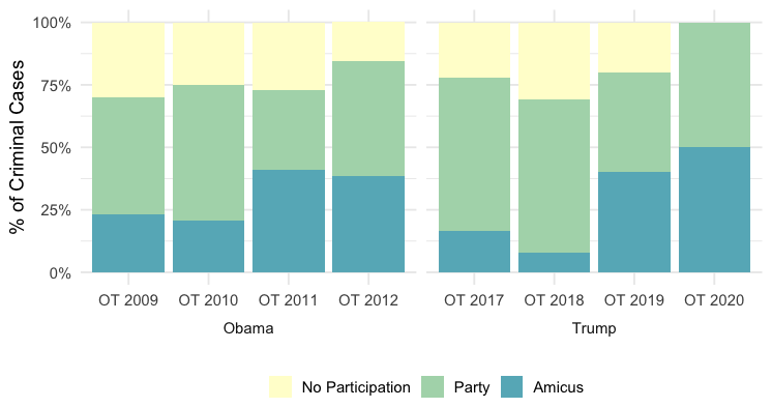

Relying on a data set compiled for our original piece, plus a data set that formed the basis for earlier scholarship in the Minnesota Law Review, we examined every Supreme Court case argued during the Trump administration and the first term of the Obama administration to compare their solicitors general’s approaches in criminal cases. (We excluded cases from the beginning of each administration, where the previous administration’s DOJ had already weighed in on which cases are heard.) Despite the two presidents’ differing political views, the solicitors general they appointed all participated, either as a party or amicus, in over 70 percent of the criminal cases heard each October term. Some terms, the solicitor general participated in as many as 80 percent of the criminal cases argued at the Supreme Court.

Despite modest differences in the breakdown of how each administration participated in criminal cases — as a party versus as an amicus — each had similar overall participation rates: 79 percent under Trump and 74 percent under Obama. And they predominantly came down on the side of prosecutors. As a senior attorney in the Office of the Solicitor General explained to us during an interview for our law review article: “In criminal cases, we know that if we are going to enter the case as an amicus we will do so on a particular side.”

One area where the two administrations did part ways somewhat was in the small universe of criminal cases in which the solicitor general confessed error. This tradition, in which the solicitor general occasionally admits that a lower court erred in siding with the government, is another mechanism that an administration committed to criminal justice could use to course-correct by siding with defendants — thereby reducing the power of prosecutors and carceral reach. Unlike most attorneys, who are required by the rules of professional ethics to abide by their clients’ objectives (even those with which they don’t agree), the solicitor general has no client issuing specific directives. Confessing error is often touted as evidence of the office’s commitment to “doing justice.” It is thus an underexplored tool for a DOJ that recognizes the societal harms caused by mass incarceration.

The Obama and Trump administrations confessed error in criminal cases at slightly different rates. Under Obama, five of the solicitor general’s nine total confessions of error took place in criminal cases. Under Trump, only one of eleven confessions of error was in a criminal case. Although the Obama administration confessed error in a higher percentage of criminal cases during its first term than did the Trump administration, five cases is still paltry compared to the court’s entire federal criminal docket during those years.

| President | Total Criminal Cases at the Court | Criminal Cases with SG Participation | Total Criminal Cases with SG as Party | SG Confessions of Error in Criminal Cases | SG Confessions of Error in Civil Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obama | 89 | 74% | 40 | 5 | 4 |

| Trump | 47 | 79% | 26 | 1 | 10 |

Although there are 2.3 million people in prisons and jails, and millions more subject to other forms of state control, solicitors general appointed by Presidents Obama and Trump repeatedly took party and amicus positions that would worsen mass incarceration. For example, the U.S. Sentencing Commission has, over time, lowered presumptive sentencing ranges and mandatory minimum sentences for certain offenses (including methamphetamine trafficking), citing the specific goal of reducing federal prison overcrowding. Solicitors general under both Obama and Trump nevertheless repeatedly tried to limit the extent to which those changes could apply to individuals who had already been sentenced under an earlier, more punitive sentencing scheme. They similarly opposed efforts by defendants to be resentenced after judges miscalculated the relevant sentencing guideline ranges.

Solicitors general under both administrations also regularly entered cases about the legality of state court convictions as an amicus in order to advocate for pro-government positions likely to contribute to mass incarceration. For example, Trump’s solicitor general helped Kansas convince the Supreme Court that police can stop cars if a license plate search reveals that the car’s registered owner has a suspended license, even if the officer has no idea who’s driving — thus paving the way for pretextual stops. During the Obama administration, the solicitor general’s office supported Utah’s winning argument that the discovery of an outstanding warrant makes evidence seized during an arrest admissible in court even if the investigatory stop that led police to find the warrant was illegal. As Justice Sonia Sotomayor noted in dissent, these invasive stops are likely to fall hardest on communities of color, and many cities and counties have huge backlogs of outstanding warrants for things like traffic offenses and unpaid tickets.

By federal statute, the solicitor general’s sole charge is to represent the so-called “interests of the United States,” an amorphous concept that the solicitor general has tremendous discretion to define. A solicitor general committed to containing the damage of decades of mass incarceration should simply stay out of many more state criminal cases, recognizing that these cases do not implicate federal interests. Such cases include those concerning issues that do not affect the functioning of the federal government, such as habeas review of state court convictions. But the solicitor general should also think seriously before entering cases about state laws and practices that do not, or only very minimally, implicate the federal government. There is no compelling reason for the solicitor general to weigh in on the constitutionality of an insanity defense standard that a small number of states has adopted but has never been federal law, or what constitutes reasonable suspicion to stop someone for drunk driving — a crime that’s almost never prosecuted in federal court.

And when the solicitor general does feel that the court should hear the federal government’s perspective in a criminal case to which it’s not a party, he or she should recognize that the interests of the United States do not necessarily favor prosecutors. Last term, the Trump administration’s solicitor general argued, and the Supreme Court agreed, that an officer’s use of excessive force can constitute a Fourth Amendment seizure, even if the defendant ultimately escapes. More recently, Prelogar, President Biden’s acting solicitor general and whom he has selected to lead the office, reversed the Trump administration’s position in a case dealing with sentencing reductions for certain offenses involving crack cocaine under the First Step Act (although the court ultimately disagreed).

Going forward, if a solicitor general’s supposed commitment to “doing justice” is to be taken seriously, he or she should account for the ways in which increased prosecution and mass incarceration harm society when considering whether to defend a lower court’s judgment or support a state or local government as an amicus. This reckoning should be bipartisan. Like President Biden, Presidents Trump and Obama recognized the need to shrink the federal prison population. In 2020 alone, more than ninety percent of those convicted in the federal system were given prison sentences. And federal prisons are at 103 percent of their maximum capacity, despite the ongoing pandemic.

Reducing, rather than increasing, America’s prison population can and should be the goal of solicitors general appointed by presidents of both parties. But especially for President Biden, who has already nominated many public defenders and civil rights lawyers to restore balance to a federal bench stacked with prosecutors, his choice of solicitor general could be a refreshing acknowledgment that he is cognizant of how this role also shapes the law. And that for far too long, it has been in serious need of course-correction.

Image: Unsplash