In a gritty corner of suburban Denver, near where I lived and taught for many years, a line of warehouses looks onto the blue façade of a prison entrance.

An unassuming parking lot and a row of flags — Colorado, the United States, and private prison corporation GEO Group — clash with the high concrete walls and razor wire that top the perimeter fencing. From the street, the inside is invisible, Kamyar Samimi’s death announced through the bureaucratic version of a whisper: a simple news release claiming he “fell ill” before dying. From the inside, the street is a world away, the activists who regularly hold vigils and encampments, who park their mobile reception vehicle there, are unseen and unheard by the people who GEO holds on behalf of federal immigration authorities. In immigration prisons, mundane administrative decision-making masks physical trauma and violence. Under President Obama, they thrived. In the era of Donald Trump, they were glorified. Under President Biden, they should close. Instead, they are filling.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the Department of Homeland Security unit charged with enforcing federal immigration laws in the nation’s interior, finances a sprawling network of county jails and private detention centers in which it holds people waiting to learn whether they will be allowed to remain in the United States. As the federal government’s chief immigration enforcement agency, ICE mostly relies on county sheriffs’ departments and private corporations like GEO and its main competitor, CoreCivic, to operate immigration prisons. Sometimes ICE essentially rents beds in the county jails that sheriffs run. Other times it contracts with a private prison company to staff entire facilities.

Abuses inside these facilities are legion. At the suburban Denver facility where ICE agents held Mr. Samimi after they arrested him at home in 2017, two weeks was all that this 40-year resident of the United States could handle. He got sick, “became unresponsive,” then died at a local hospital, ICE’s news release announced. An internal agency review released more than a year later, revealed that prison staff took away his methadone, ignored his complaints, and didn’t monitor his symptoms using standard medical processes. Staff failed to comply with 12 of ICE’s detention standards, the review found, and had trouble reaching the facility’s doctor.

Today, the facility where Mr. Samimi died remains operational. No one has died there under Biden’s watch, but illness and death remain a concern. As of May 5, 111 of the 502 people detained there were being monitored for Covid; and 36 were quarantined or cohorted because they showed symptoms of the disease.

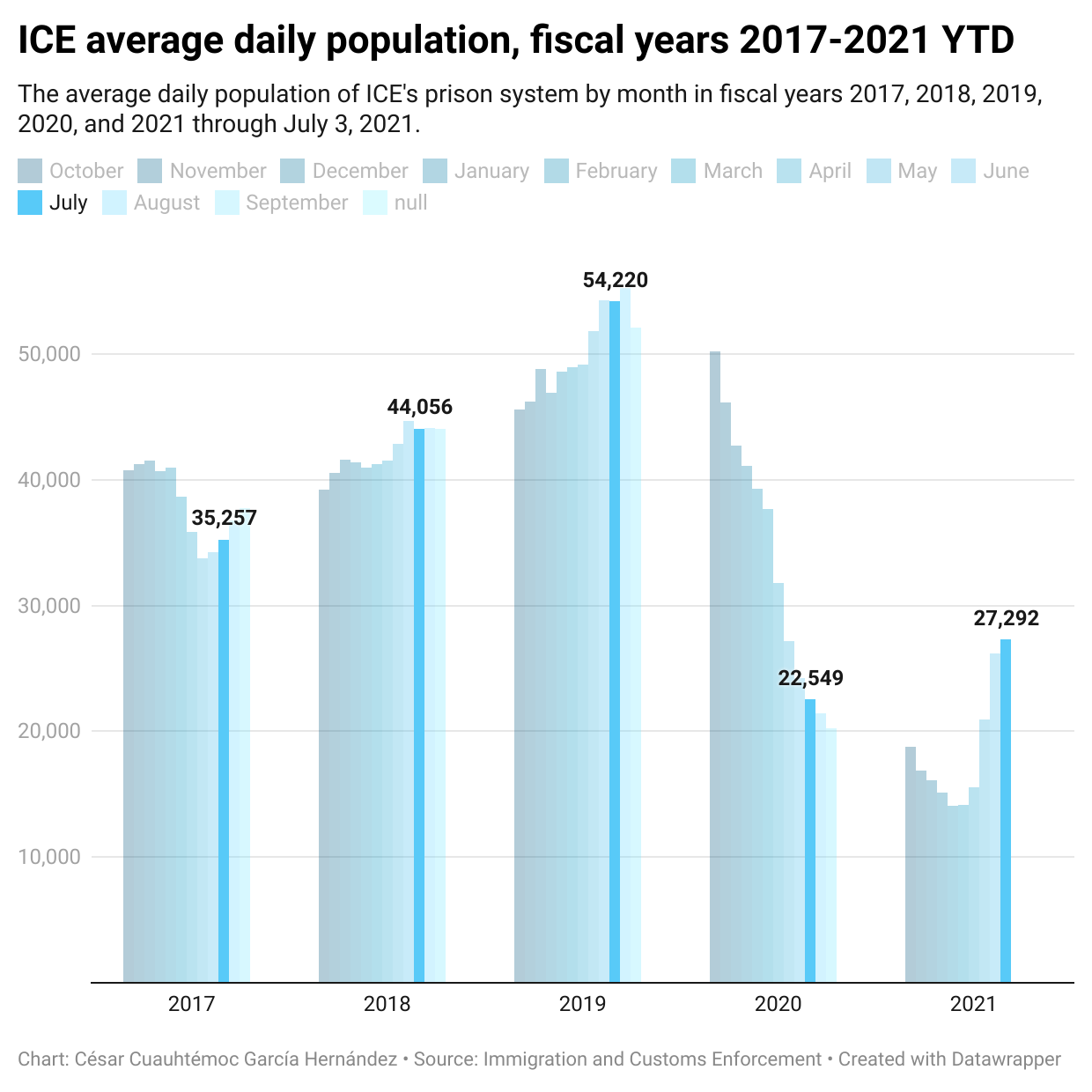

Under President Trump, ICE’s prison population grew to record highs before plummeting. For seven months in 2019, ICE’s average daily population surpassed 50,000, topping off at 55,238 in August 2019. The pandemic changed all that. At the end of Trump’s presidency, the average daily population in ICE’s prison network had fallen to 15,104, fewer people than the agency had detained since its creation in 2003.

For all his talk of parting ways from President Trump’s vilification of migrants, President Biden has yet to push ICE’s prison operations in a starkly different direction. After dropping in February and March 2021, ICE’s average daily population began to increase in April. By early May, ICE’s prisoner population count had surpassed the Trump-era low and seemed headed back toward the days of President Obama when the agency regularly detained more than 30,000 people on a given day.

Despite ICE’s heavy reliance on imprisonment to enforce immigration law and its willingness to stomach troubling detention conditions, both are often a policy choice. Some of ICE’s detainees are subject to a federal statute that prohibits ICE or immigration judges from allowing their release. In early July, this described 11,990 of the agency’s average daily population of 27,217 (44 percent). But the rest are held subject to discretionary powers, meaning that ICE agents and immigration judges are supposed to release them unless they are unlikely to show up for court dates or likely to endanger the public.

Independent of the legal basis for confinement, the Biden administration can use its immense executive authority to reduce ICE’s prison population quickly, legally, and unilaterally. The immigration bureaucracy extends across several agencies and its laws are unwieldy, but the administration has several options to set people free and keep the detained population at historic lows. For people already in detention or those at its front door, the Justice Department and DHS simply have to choose to unravel the prison’s clutch.

When it comes to people whom Congress has purportedly pushed beyond the reach of immigration judges, the Justice Department could adopt policies favoring release from detention. Added to federal immigration law by the Clinton-era Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, the so-called mandatory detention provision of immigration law doesn’t actually say anything about detention. Instead, it requires “custody,” a term that is anything but unique to immigration law. In other contexts, courts often say many restraints on liberty — from full-on imprisonment to a paroled prisoner’s requirement to hold a job —qualifies. But in 2009, the nation’s top immigration review agency — a Justice Department unit called the Board of Immigration Appeals — took custody to be synonymous with detention. With one decision, the Board or its top supervisor, Attorney General Merrick Garland, could reinterpret immigration law to fit more neatly with other areas of law and, in the process, enable more people to petition for release from ICE’s grip. An immigration judge could turn down the request, but at least migrants could ask.

Under President Obama, immigration prisons thrived. In the era of Donald Trump, they were glorified. Under President Biden, they should close. Instead, they are filling.

César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández

Meanwhile, for the 56 percent of people detained in early July who could be released, options abound. ICE and immigration judges are supposed to consider whether a person in ICE’s custody is likely to endanger the public or skip court dates. For its part, ICE uses a secretive algorithm that almost always concludes that the risk is too high. DHS could toss the computerized risk assessment if it wanted to, leaving ICE agents and immigration judges to make these decisions in light of existing laws and government policies, but so far Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas has shown no sign that it’s considering this. And immigration judges don’t weigh in unless a person asks for a bond hearing, a procedural step that migrants who are not represented by lawyers often don’t know to ask for. When immigration judges do get involved, they are barred from considering a person’s ability to pay and subject to Trump-era workload pressures that prioritize final decisions over thoughtful deliberations.

With Garland at the helm, the Justice Department could transform immigration-court operations without waiting for Congress to change a word of the immigration-law statutes. To start, Garland could rescind the Trump administration’s 2019 order instructing immigration judges to hold asylum applicants in federal custody until officials reach a decision on their applications. Though the order of Trump’s attorney general, William Barr, claimed that “there is no way to apply” the relevant provisions of immigration law except to demand confinement, the opposite was true for most of ICE’s history. In 2005, when George W. Bush was in the White House, the Board of Immigration Appeals, comprised of members appointed by the attorney general, concluded that immigration judges had the discretion to release or detain migrants who had shown a credible fear of persecution if forcibly removed from the United States, a critical step toward obtaining asylum. Returning discretion to immigration judges would allow people who have requested safe harbor in the United States to pursue their legal claims without the yoke of confinement. The Justice Department has recently shown some willingness to exercise its immense powers of immigration law. In June, Garland revoked the decision by Trump’s first attorney general, Jeff Sessions, to effectively bar survivors of domestic violence or gang violence from qualifying for asylum, instead reinstating a 2014 decision that opened a pathway to asylum for people fleeing situations that are sadly all too common in Central America today.

Beyond these steps, two further moves would reduce the number of people who are swept into the system — and ensure minimal standards of safety for those who ultimately end up being detained. The administration could direct DHS to alter its enforcement practices to rely less on local law enforcement agencies, which would inject fewer people into immigration prisons. The Biden administration inherited almost 150 agreements between ICE and local police and sheriff’s departments, all of which remain in place and are big drivers of detention. Through these partnerships — known as 287(g) agreements, in reference to the section of federal immigration law that authorizes their use — encounters with local police officers often lead to life-altering entry into ICE’s immigration prison system. There is no exception for lawful permanent residents with green cards in hand or people who haven’t committed a crime but lack the government’s permission to be here. By continuing to respect Trump-era agreements, the Biden administration is sending the message that its predecessor’s policies, if not its rhetoric, are acceptable.

And in May, the administration hinted at what’s possible when ICE announced that it would end its contracts with two facilities — a county jail in Massachusetts and a county-owned prison in Georgia operated by a private prison company. One year earlier, sheriff’s deputies at that Massachusetts jail violated the civil rights of ICE’s detainees by using “excessive and disproportionate” force, the state attorney general found. The Georgia facility, a former nurse there complained in 2020, sent women to a gynecologist who needlessly performed hysterectomies, often without fully informing the women about their options. Closing these two facilities will have a limited direct impact. By the time the agency’s decision was announced, approximately 120 of 1,200 beds were in use between the two sites. What these closures lack in direct impact, they make up for in symbolism. ICE rarely exercises its option to terminate contracts over poor conditions, so its decision to cut off ties to the Massachusetts and Georgia facilities suggests a newfound appreciation that when it comes to detaining migrants, there does indeed exist a floor for what the federal government views as acceptable treatment.

From the very top, administration officials know well the horrors of ICE’s prison practices. On the campaign trail, President Biden promised that, if elected, no one would profit from locking up people seeking asylum in the United States. And Mayorkas, who leads Homeland Security, said that ICE facilities are “not where a family belongs.” So far, neither commitment has become reality. And as Mr. Samimi’s family knows well, sometimes it only takes a few days in ICE’s hold before preventable death arrives.

The administration could use existing legal authority to limit confinement, but so far it has largely failed to do so. Instead, the rising number of people detained by ICE suggests that the Biden administration is likely to turn the low population counts during the closing months of the Trump administration into a floor rather than a ceiling. With options for an alternative future in hand, though, the growing number of imprisoned migrants whiffs of a policy choice rather than a legal mandate.

Image: Unsplash