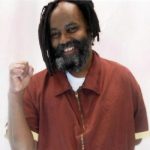

Mumia Abu-Jamal is likely the most well-known political prisoner in the United States. Before his incarceration, Abu-Jamal was already an astute critic of the carceral state, using his platform as a Philadelphia radio journalist to bring attention to the violence meted out by police against the city’s Black citizens. In 1981 Abu-Jamal was sentenced to death for the murder of a Philadelphia police officer. Although the Superior Court of Pennsylvania would eventually overturn the death sentence, Abu-Jamal remains incarcerated on a life-without-parole sentence.

Both at the time and throughout subsequent decades, Abu-Jamal’s conviction has been widely criticized by domestic and international human rights organizations. For many Americans involved in the fight to end mass incarceration, the fight to “Free Mumia” was their on-ramp, with Abu-Jamal’s books, interviews, articles, and radio programs helping them to connect their outrage over his specific case to a more holistic analysis of the intersection between systemic racism and the criminal legal system.

Abu-Jamal’s most recent book, a collaboration with literary scholar and activist Jennifer Black, is a slight departure, at least in genre, from his previous works. Rather than a collection of original essays, Beneath the Mountain: An Anti-Prison Reader leapfrogs through eras to assemble some of the most potent writing against incarceration, stretching all the way from nineteenth-century anti-slavery luminaries Frederick Douglass and John Brown to more recently writings by Assata Shakur, Malcolm X, and many others connected to twentieth-century freedom struggles. The result is a book that, though well-suited for solitary contemplation, would unquestionably come alive in classrooms, reading groups, and political education circles.

In the following interview, Inquest’s managing editor Adam McGee discusses with coeditors Black and Abu-Jamal how they came to work together and how they envision the anthology being useful in the work of ending prisons.

Adam McGee: So much of the violence of prisons is in how they aim to keep the people inside separated from everyone else and, whenever possible, invisible. Given that, Jennifer, maybe you can start us off by saying how you got to know Mumia and work with him.

Jennifer Black: I grew up in Pennsylvania, but I was drawn into the Free Mumia movement in the early 1990s when a family member learned about him while visiting Berlin. It was shocking to me that, first, an injustice of the magnitude of what happened to Mumia in 1981 had occurred in my home state, and, second, that he was on death row just thirty miles from where I lived yet it had taken a trip abroad to hear about his case.

The invisibility of incarcerated people is on purpose. It’s by design, and it is part of what allows so many grave human rights violations associated with incarceration to perpetuate. The experience of getting to know Mumia, joining the movement that demanded justice on his behalf, and learning about the phenomenon of mass incarceration was an education more powerful than anything I had ever learned in a formal classroom.

When Mumia and I decided to do this book, it was after many conversations and years of knowing each other. Our preparation and initial plans went very smoothly—after all, we study, teach, research, and write about this stuff! Not to mention that Mumia has been living in prison since 1981, so he has really deep knowledge about how to navigate the numerous impediments it places on communication. We sat together in the visiting room of SCI Mahanoy, over shared vending machine snacks, and easily came up with an initial list of people we wanted in the book.

The first suggestion for people to include was an obvious one: Mumia was the one who had suggested back in 2015 that I read Prison Writings: My Life Is My Sundance, the autobiography of maligned American Indian Movement activist Leonard Peltier, a political prisoner currently serving a double life sentence. Mumia thought it would be a great addition to the syllabus for a class on prison literature that I was prepared to teach at the Ohio State University. So I wasn’t surprised that, when we started sketching out the table of contents for Beneath the Mountain, Mumia pointedly declared: “Leonard. Leonard has to be in the book.” Of course, I agreed.

The book flowed, like water, from there. After we came up with a list of people—a list that got longer and longer—the next step was to determine just which essay or chapter or speech or letter we would use. Sometimes this was an obvious decision but sometimes it took back and forth over letters and in person to decide. We kept adding people to the book until it became quite lengthy. Writing the introduction was interesting and, for me, a bit intimidating: Me, alongside the mighty and great Mumia Abu-Jamal? But it got done. We took turns taking the lead on writing, with the other person coming in to add their suggestions and edits. The entire process took about eighteen months as we both have other commitments and projects we work on. As always, Mumia was the MVP and the GOAT. What he is able to accomplish from his cage, with no access to the Internet or a decent library, and with all his communications surveilled on the way in and on the way out, is truly miraculous.

Although we still had to leave out so many people we would have liked to include, we are happy with the finished product. Each contribution has a special significance and relevance for me, as each has been a signpost in the development of my anti-prison consciousness. So far, the feedback we’re getting from people is that they’re surprised by the breadth of the contributions, and most readers seem to be discovering at least some people they weren’t previously familiar with. We aim to get this book into as many libraries as possible, and into the hands of as many incarcerated people as we can. Hopefully people who read this book will become familiar with someone new.

McGee: Where did the idea for this book begin? Was there a private version of it already in existence as a collection of personal favorite readings, and it grew from that? Or was it something that really began with a consideration for what a specific audience might need at this moment?

Mumia Abu-Jamal: I think Jennifer initiated the idea during our conversations around prisons and the fact that there are so many deep readers in prisons (especially in an age where students seem to be reading less!)—kinda like: “Ya know what’d be cool? A book specifically for prisoners, with excerpts from Great Books, yeah?” The idea was addictive, especially as the abolitionist movement began to pop and bubble.

Black: I remember it like Mumia remembers. But the idea came from all the years spent watching Mumia, who is an incredible public intellectual, study, write, and publish from the confines of a cage. He is prolific and it really moves me to see how dedicated he is to his goals and ideals, and how much institutional bureaucracy he has to overcome just to get materials. That, and doing a lot of educational support work for people on the inside and being a witness to how much wisdom and knowledge and brilliance there is amongst incarcerated intellectuals. I have been inspired by the incarcerated radical tradition and by the political education that happens in prisons. I hoped we could create a book that would stand in the canon of that tradition as both a testament to it and an example of it.

McGee: What does it mean to you to be trapped “beneath the mountain,” as in the book’s title? How are our lives presently constrained by the weight of the mountain, and does the mountain weigh equally on everyone?

Abu-Jamal: “The mountain” is, of course, a metaphor for the ever-present (and rarely discussed) weight of repression versus the People. If we don’t speak on it, how do we oppose it? How can it be beaten? How do we oppose it? How can it be resisted?

Black: Right! I like how Mumia explains it. Mountains are figurative and symbolic, but they’re literal as well. Living in Central Pennsylvania, in a valley, I drive through a lot of mountainous terrain while visiting different prisons. I drive through mountains when I visit Mumia at SCI Mahanoy, and mountains again when going the other direction, where he used to reside on death row at SCI Huntingdon. The mountaintop represents glory, freedom, and the promised land; the regions beneath the mountain are modern-day dungeons.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

McGee: What audience did you have in mind as you were compiling the book? And for an audience of people who are already committed to ending mass incarceration, how would you encourage them to approach the book? What lessons or inspiration would you hope they would take from it?

Abu-Jamal: When Black Lives Matter was raisin’ the roof, many movement activists began thinking about the abolition of repressive systems, utilizing popular resentments to fuel such a call, such as the invitation screaming from graffiti on the walls: “Defund the Police!” This put me in mind of Angela Y. Davis’s 2003 work, Are Prisons Obsolete? I remember reading it years ago (actually, I had a prepublication copy), and I was stunned by the boldness of her analysis. I remember speaking with my big sister, Lydia Barashango, and our conversation went something like this:

LB: Whatchu reading these days, bro? MAJ: Sis, I just finished Angela Davis’s new book and it got me thinkin’. LB: Is it about what I think it’s about? MAJ: You thinkin’ ’bout abolishing prisons? LB: Listen, Mu; I’m a Black nationalist, but: Heyyyyy—I ain’t ready for that! That’s too radical! [laughing] MAJ: Lit! Lit! I gotta tell ya, she makes a lotta sense! LB: Heyyyy, Mu! I ain’t ready! Some of these dudes needs to be locked up! I’m just sayin’! Know what I mean? MAJ: I hear you, sis. But she sez these joints should be staffed to educate cats—and education is the only thing that works, dig? LB: Nah, Mu! Nàwwwww! Um-umm. I can’t get with that. [laughing]

That was the gist of our conversation. In any event, Davis’s book was an event where ideas of abolition broke through. The BLM movement and the George Floyd demonstrations (which were global!) were, too, moments when abolition broke through the walls of media and bourgeois politics. So, when we think about abolition, we should remember these social movements and historical lessons allow us to see the time-scape of social change movements, when people demanded systemic changes in society. For example, in the natal years of the French Revolution, the people attacked and destroyed the dreaded Bastille prison in France. They didn’t ask their political leaders to pass a resolution. They didn’t petition the court for a court order. They tore it to pieces. And lifted that dark cloud of repression from the minds and hearts of French revolutionaries. So, when you look at those vast numbers of folk who protested, we see all of them as potential readers of our work. Or most of them!

Black: I really love that exchange between Mumia and his sister because Lydia, who has since joined the ancestors, represents a subset of people whose lives have been negatively impacted by state terror and incarceration but who stop short of endorsing abolition. I think it’s helpful to see just how far back anti-prison sentiment stretches and our book helps demonstrate how essential pro-prison sentiment has been for the people who strive to stay in power. This can have a politicizing effect, and perhaps be a bridge that leads people from being generally suspicious of the role of policing and punishment to being more firmly anti-prison. We dedicated the book to those who reside “beneath the mountain.” Throughout the process of developing the book we kept the interests and needs of incarcerated learners at the heart of our mission. Beyond incarcerated readers, we also wanted to appeal to other intellectually curious, self-taught students who might not have access to university libraries, databases, or the acumen of esteemed professors.

But beyond prison pedagogy, Mumia and I are also steeped in traditional academia as well. Mumia is currently writing his doctoral dissertation after already earning a bachelor’s and an master’s. And I teach at Penn State University after years studying and working at The Ohio State University where I earned a doctorate in Comparative Studies (I wrote my dissertation on Mumia). Therefore, we know a compilation like this can be a helpful tool to those who learn and teach about carceral issues, social movements, and prison literature, and we strived to create a book that would be relevant whether it was being read in a cage or a classroom. It’s a good book for people just beginning to think about anti-prison consciousness—but I think people who are already steeped in abolitionist thought, theory, and practice can also learn so much from the wisdom of the contributors, even though they may be familiar with many (though probably not all) of the writers in the book. Why do people commit their lives to social movements? When organizing in dangerous times and dangerous places, what inspires unity and solidarity? What role does the state play in maintaining the status quo? How do people inside prisons organize on behalf of their own interests? Why is it so crucial to develop anti-prison consciousness, and what is the role of political education? The collective wisdom within this book helps to answer these questions. Moreover, they are examples of courage. Each contributor, spanning from the late 1700s up until 2024, is a teacher.

McGee: In the book’s introduction, you theorize a connection between anti-literacy laws under slavery and present-day book banning, anti-“woke” legislation, and prohibitions some states have attempted to enact against the teaching of Black history and ethnic studies. Your book, then, makes me think about the fugitive act of enslaved people risking their lives to teach one another how to read. Can you talk about how your book fits into that kind of history of teaching as a form of mutual aid? And of the long radical tradition of compiling readers as part of political education?

Abu-Jamal: Mass incarceration is an updated expression of the social institution of slavery—i.e., neoslavery. In other works, we’ve reported state repression of Black radicals—many of whom have existed in solitary confinement for decades! (Examples include Ruchell Magee and Russell Shoatz.) Thus, we learn how history enriches and deepens our understanding of our present.

Black: I think one of the powerful threads woven throughout Beneath the Mountain is about the power of education and its role in the development of political consciousness. Frederick Douglass represents this because one of the things he is known for is teaching himself to read as an enslaved child. Then he is able to represent to the world his experiences under the slaveocracy in a series of autobiographies, which detail the horrors of slavery, including his stint in prison. Malcolm X’s jailhouse conversion to Islam and subsequent self-education journey emancipated his mind in advance of his actual physical release from prison. In her essay in the book, Assata Shakur emphasizes the need for more political consciousness amongst the women she was locked up with. And everyone who served time with him knows that Russell “Maroon” Shoatz educated generations of men—including Robert Saleem Holbrook, executive director of the Abolitionist Law Center, who wrote the final essay in the book. It’s a genealogy. It’s the radical incarcerated tradition and is one of the connecting cords throughout the book. How can we not learn from all of these experiences?

Image: Daniel Lobo/Flickr/Inquest