As a physician in Atlanta, I work with many patients who come from marginalized and neglected communities, many suffering from what Ruth Wilson Gilmore describes as organized abandonment. Alongside other local health-care workers and students, I have advocated for people’s release from detention and alternatives to incarceration—driven by the reality that a multitude of negative health consequences stem from criminalization and incarceration. In clinics and hospitals across Atlanta we see vividly the unmet needs of patients. We also see that the political choices city and county officials make—where and what to invest in—constitute structural violence that ultimately leads to preventable suffering and premature death. In a city and county where racialized inequality is the norm, the criminal legal system remains the primary institution “provided” to low-income Black residents.

The horrifying death of Lashawn Thompson at the Fulton County Jail in September 2022, one of at least fifteen that year, is illustrative of a problem that is entirely preventable. He died in the so-called “mental health wing” of the main jail on Rice Street, after being detained for three months for a misdemeanor, unable to afford his bail. His death, for which the family commissioned a private medical review, was attributed to complications from severe neglect—with untreated schizophrenia, dehydration, malnutrition, and severe untreated insect infestations all serving as contributing factors. Confined for months, decompensating and unaided, Thompson, like so many others in custody, died a death that was not inevitable. Since July 2023, motivated in part by this tragedy, the Department of Justice has placed the entire Fulton County Jail under the microscope.

Thompson died only a month after elected officials approved a controversial new jail lease in Fulton County—Georgia’s most populous county and home to 90 percent of Atlanta’s residents. Despite decades of reforms, litigation, financial investments, new contractors, and new leadership, Fulton County’s sole strategy to address the pervasive conditions of violence, suffering, and abuse in its facilities has been to simply obtain more space, no matter the financial and opportunity costs. In 2021, at the height of COVID-19, instead of taking decarceration for public health reasons more seriously, Fulton claimed it needed more space, and so jail officials sent a hundred people to neighboring Cobb County’s jail. Today, a few hundred people are still shuffled around to surrounding county jails, at significant cost, because space, we’re told time and again, is the primary issue.

To acquire even more space, Fulton County sheriff Patrick Labat, elected in 2020, sought to lease the city of Atlanta’s jail, the same one he presided over as chief jailer before his election. The Atlanta City Detention Center (ACDC), a 1,300-bed facility built for the 1996 Olympics, has sat nearly empty for years, ever since advocates pushed the city to end its contract with ICE in 2018. With fewer than 25 people incarcerated on a given day, at a cost of over $18 million, ACDC was slated to be transformed into a community resource center. Former Atlanta mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms even signed legislation planning to repurpose the space in 2019.

With plans in place for the repurposing of ACDC and the redirection of Atlanta’s outsize correctional budget to community-based resources, the Atlanta City Council and new mayor Andre Dickens needed a narrative to justify favoring the sheriff’s plan and abandoning the work of a large and diverse coalition that fought hard for this change. Following the uprisings of 2020, simple “tough on crime” rhetoric proved more difficult for manufacturing consent of the public, so officials found their narrative in the language of compassion. Officials pointed out that, due to persistent overcrowding, a few hundred people were sleeping on the floor of the Fulton County Jail on any given night. The mayor called this a humanitarian crisis and the urgent need to lease ACDC a “humanitarian” intervention. In this way, he could assure the public they were doing this for the right reasons. He also reassured advocates that Atlanta was not in the “jailing business”—a contradiction that stood at odds with the plan to lease 700 jail beds for explicitly this purpose. In lending support to the four-year lease, Fulton County commissioner Natalie Hall stated, “If you care about just people in general, you would want to do something to relieve this situation.”

Many of us, in fact, did want to do something about it—by shrinking, not expanding, Atlanta and Fulton County’s carceral footprint.

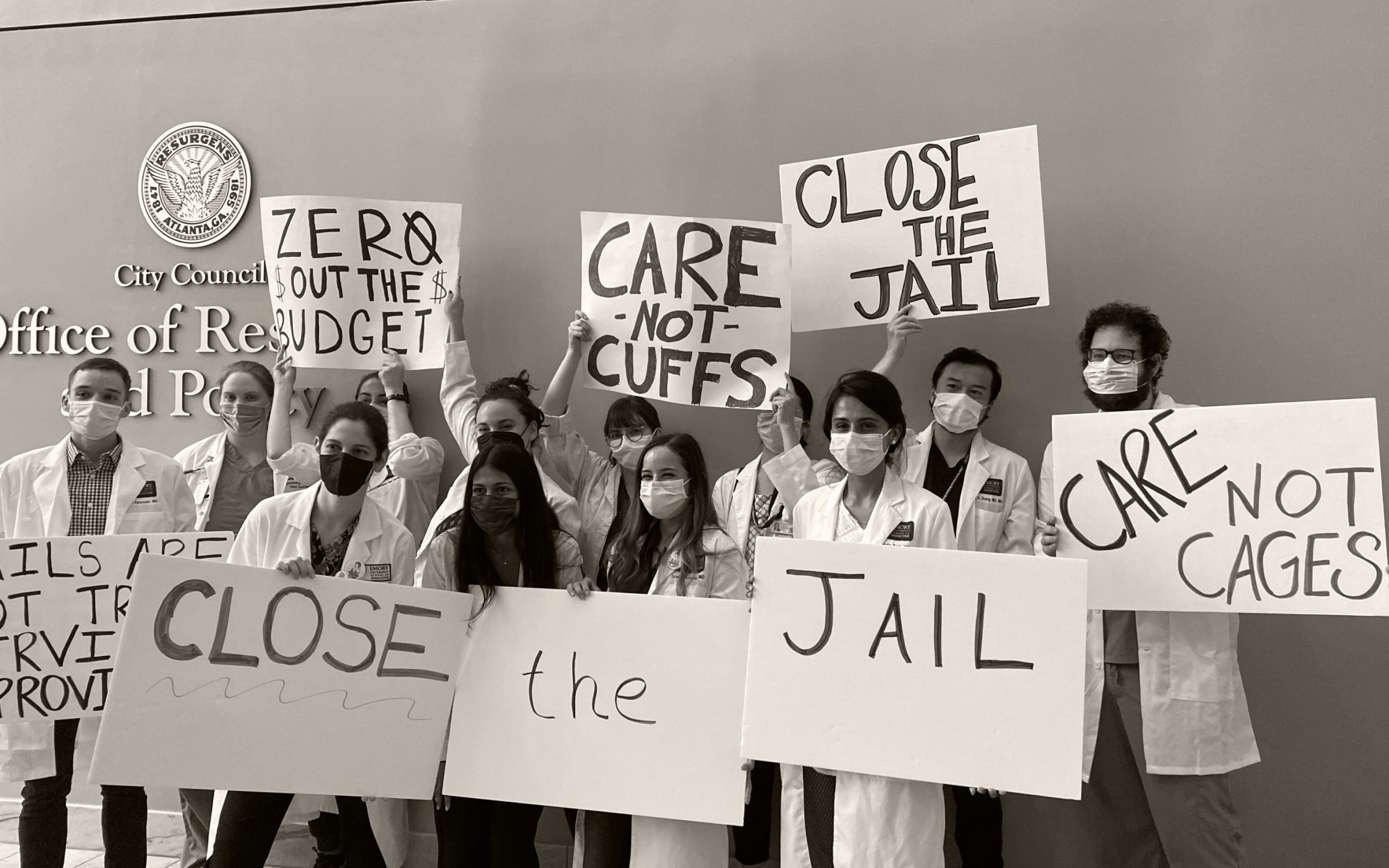

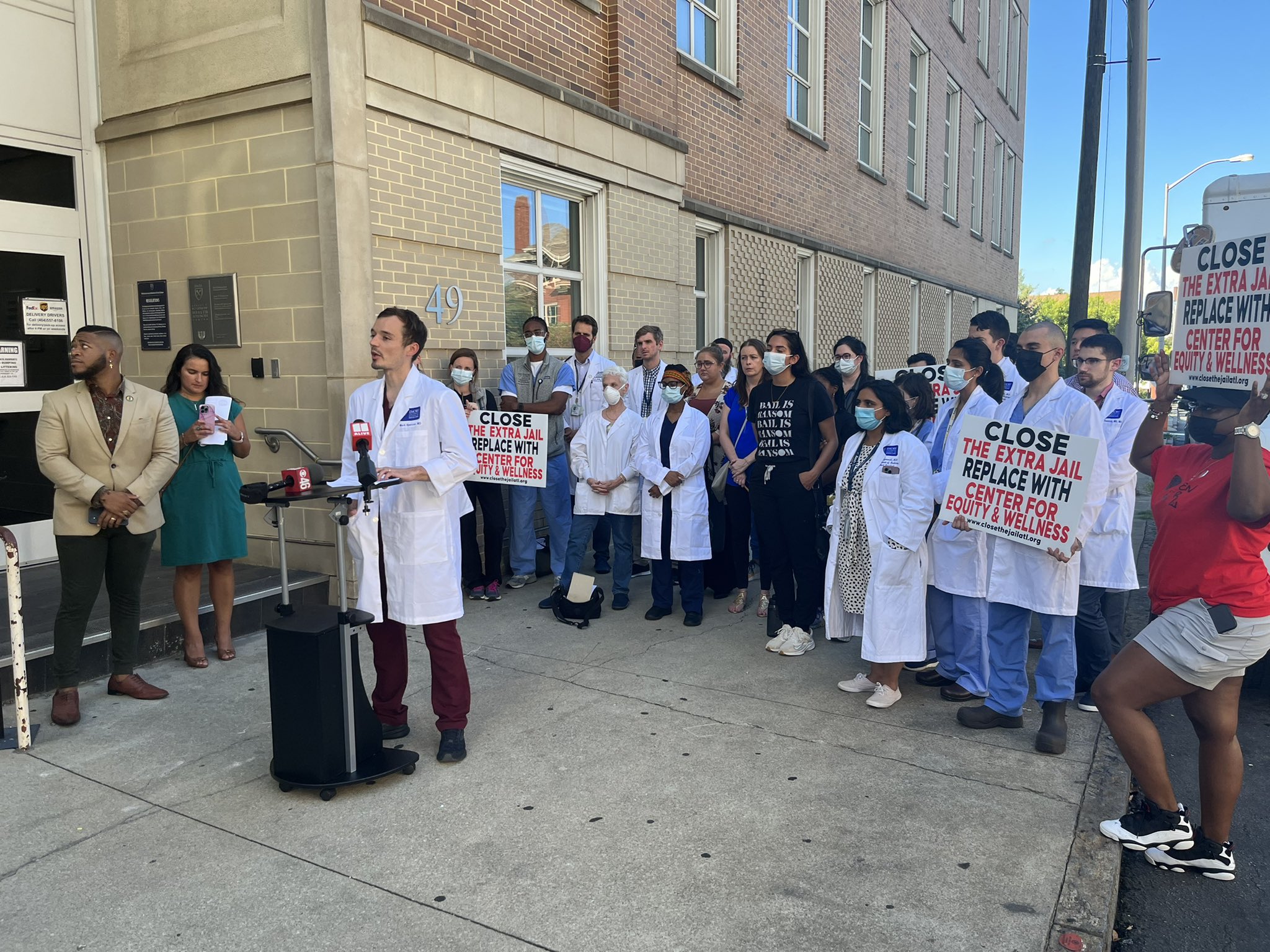

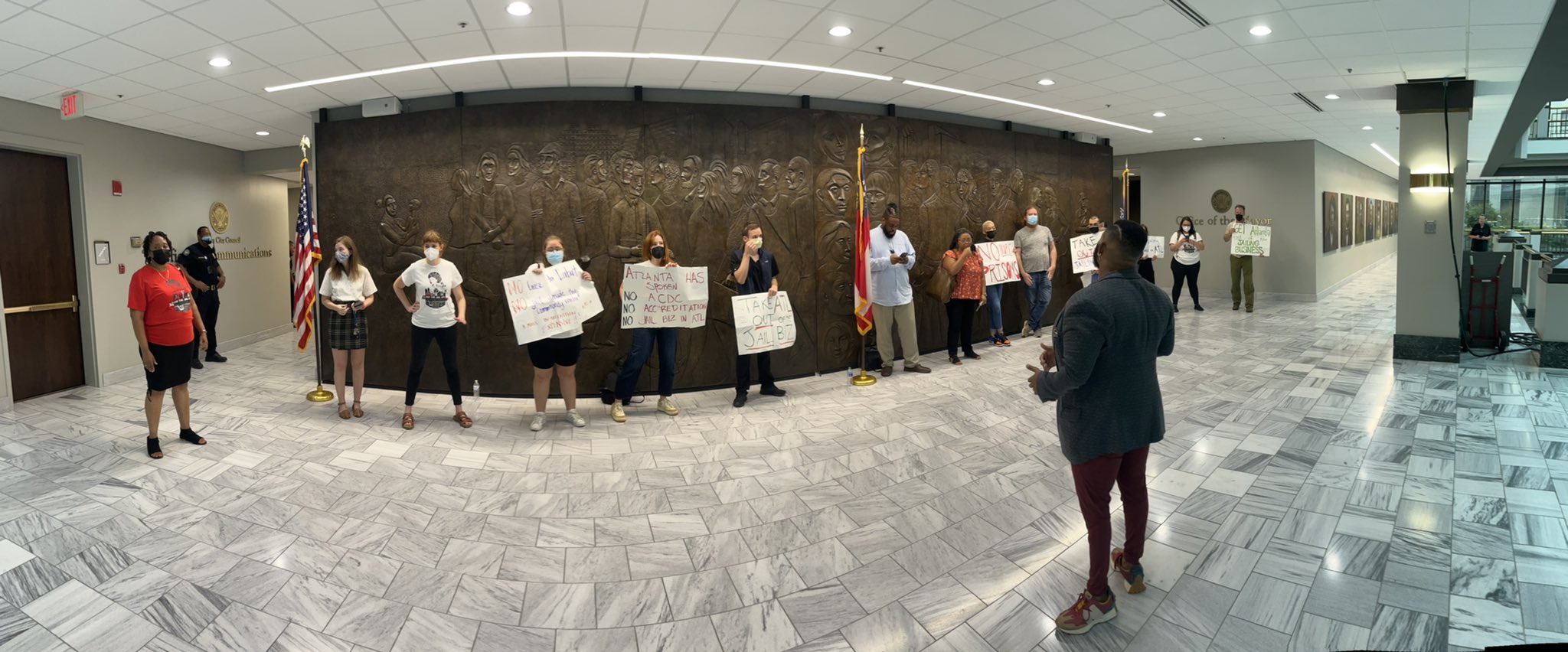

As the Fulton sheriff and Atlanta mayor ramped up their public campaign to convince people of the humanitarian need for additional jail space, our coalition of Atlanta health-care workers vocally supported the Communities Over Cages Campaign to close ACDC once and for all and replace it with the John Lewis Center for Equity and Freedom. Over 300 Atlanta health-care workers and students signed our open letter to the city council prior to voting on the bill. We held press events, wrote opinion pieces, held teach-ins for other health-care workers, and showed up to city hall consistently for public comment. Through sharing our experiences and data on health outcomes with the city council, we added one more voice to an already robust coalition of formerly incarcerated individuals, lawyers, advocates, community members, and social service providers.

We made it clear that we were not to be swayed by the language of humanitarianism, telling the mayor that “to talk of humanitarianism in terms of only the number of cages for human beings is quite something.” We have seen that in Fulton County and Atlanta, punishing poverty remains more important than economic and racial justice. Here, the true humanitarian crises are people who do not have access to well-funded schools, adequate or affordable housing, healthy food, timely health care, community-based services, or jobs that pay a living wage. Rather than investing in people, local officials invest in their criminalization and incarceration.

This self-inflicted crisis of overcrowding was not new, and neither were the solutions that didn’t involve simply moving incarcerated people around. Last September, the same month of Lashawn Thompson’s death, the ACLU released a report using sheriff’s office data that made plain how over-detention was the problem in Fulton County, and that the fix was within reach: “Fulton County’s failure to account for people’s ability to pay bail, confinement of people charged only with misdemeanors, failure to timely indict people, and local law enforcement agencies’ failure to fully utilize diversion programs has led to population levels above capacity at Fulton County Jail.” Eliminate these cases, the report urged, and “the population would be reduced to levels more than sufficient to eliminate overcrowding at the Fulton County Jail.” The four-year lease, approved a year ago this August and valued at $50 per person per day paid to the city by the county, has been described as “blood money” by the organizers who had been promised the community center—and shows our elected leaders’ ongoing ideological commitment to incarceration.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the goalposts continue to shift. With the lease now in place, the sheriff is campaigning for an entirely new jail. The problem is no longer about space but about the conditions of the jail itself. Fulton County has studied the need and cost for a new county jail and has concluded that in the span of twenty-five years the county “will need a jail nearly four times the size of the current overcrowded facilities—with beds for up to 6,418 inmates.” Yet there are so many variables involved in the construction of a new jail, so many imponderables, one can conclude that this self-fulfilling study is assuming all too candidly that the root causes of criminalization and incarceration won’t change—and thus the status quo of inequality, poverty, threadbare resources for mental health and substance use, the continuing of the War on Drugs, and many other of the drivers that decarceral advocates have focused on won’t be addressed.

Here, again, is where county leaders are turning to the language of humanitarianism. With a price tag of $2.2 billion and murmurs of raising taxes to fund the massive project, the county has looked to reassure the public with an all too familiar refrain that they are doing this for the right reasons. The blueprint highlights that, “Overall, 42% of the new jail would be dedicated to services for physical and mental health, visitation, recreation and other programs.” Sheriff Labat himself has said that the current jail “represents an old way of thinking.” The apparent new way of thinking still centers incarceration as the primary public safety strategy, despite a lack of empirical evidence to support this notion. What is not new is the refusal to fund robust networks of preventative-focused community-based care.

This flowery language of carceral investments born out of care is not new in Fulton County. Strikingly similar prose has been used to justify the need for the 1986 relocation of the jail to its current location. The $1 billion “upgrades” from 2005 to 2015, required during Fulton’s previous, decade-long federal oversight, were likewise largely meant to improve the conditions for those incarcerated in the jail.

To this day, the health of incarcerated people continues to be prioritized, at least rhetorically, as these same elected officials are in part responsible for the manufactured scarcity driving incarceration in the first place. While the city and county abhor accusations of neglect, the threat of legal action, or bad publicity resulting from tragedies like Thompson’s, comparatively little remains invested in people’s health prior to their incarceration. And despite their newly leased jail space, reality remains unchanged at both locations: This past July alone, forty-year-old Montay Stinson died at Rice Street after nine months of being unable to afford his bond; and nineteen-year-old Noni Battiste-Kosoko, who was being held with no bond on a misdemeanor charge, died at the leased facility, ACDC.

The failure of expensive reform after expensive reform is not unique to Fulton County but rather emblematic of the very nature of U.S. prisons, jails, detention centers, and other carceral settings. With widespread substandard, unaccountable, and often barbaric treatment plaguing these institutions since their inception, medical neglect and poor health outcomes are defining features of incarceration. Calls to improve health services are as old as the institutions themselves. Despite a constitutional right to health care since 1976 and tens of thousands of health care–related lawsuits since, care remains substandard, violence and neglect the norm, and premature death a feature of our penal system. The inability and unwillingness to develop robust alternatives shows us the values, or lack thereof, of the punishment bureaucracy and that carceral spaces are fundamentally ill-suited to provide a therapeutic environment, let alone evidence-based care.

In the face of this bleak reality, the enduring focus on “fixing” carceral health care leaves deeper structural conversations about the system unmentioned and many paths to improving individual and collective health unexplored. It likewise serves to constrain the debate of how time, funding, and expertise should be spent. Implicit in this reinforcement of the status quo is the assumption that carceral systems must serve a worthwhile purpose, and so it is reasonable, or even desirable, to work within their existing framework. This thinking offers a window into carceral humanism, or the building of a more humane cage, and provides a subtle yet important endorsement of the criminal legal system’s punitive excesses. James Kilgore, who popularized the term, describes carceral humanism as the strategy of portraying “the jailers as caring social service providers,” with the goal of locking in these services behind prison walls and creating public support for this institutionalization.

Carceral humanism extends beyond the push to see jails and prisons as legitimate social service providers. It can also be seen through other proposed tweaks to the criminal legal system that are framed as gentler, kinder forms of control, such as drug courts or electronic surveillance programs. In the end, these structures and practices often expand the net of criminalization and continue to rely on punitive systems that do not meet the needs of those they claim to serve. Likewise, carceral humanism is seen in the push to build special juvenile “reform centers,” mental health jails, and women’s jails, all of which end up replicating the harmful environments they were framed as solutions to.

The broader public, for its part, is generally uninformed about the harms of carceral systems beyond what is portrayed in the evening news, and tends to not question the narrative of carceral humanism, which is sold to them as tax dollars well spent. Many people certainly don’t want another Lashawn Thompson, or people dying from hypothermia in Dekalb County, or the decrepit, unlivable conditions of confinement advocates are constantly condemning. But the public fails to see these highly publicized in-custody deaths and other ills as entrenched features of incarceration. Worse still, many find themselves led astray by the relentless stream of news media, police department public relations, and popular culture centering police and carceral facilities as central to public safety. This propaganda, or copaganda, primes us to view carceral humanism as “win-win”—more humane environments that also provide public safety benefits.

This dynamic is in full view in Fulton County, where many incarcerated people have a preexisting mental health diagnosis and thus new and expanded mental health resources and dedicated cells remain a top talking point among elected officials. And this push is not all that dissimilar from the city of Atlanta’s antidemocratic and environmentally degrading proposal to build a new police training facility, known as Cop City—which is simply another form of carceral humanism in that it is being sold to the general public as an effort to advance community policing and improve training.

Yet a new awareness appears to be setting in. Across the nation, health-care workers are standing in solidarity with longstanding decarceration and abolitionist movements to demand an end to manufactured scarcity and more investments in life-affirming institutions. Beyond Do No Harm, a project of Interrupting Criminalization, aims to “address the harm caused when health providers and institutions and public health researchers and institutions facilitate, participate in and support criminalization.” Likewise, Health Instead of Punishment, an initiative by Human Impact Partners, seeks to “build capacity within the field of public health for understanding and advocating for abolition of the prison industrial complex as a public health strategy.” The End Police Violence Collective, a group of public health practitioners, researchers, and organizers, approaches state violence as a public health issue and worked to pass the American Public Health Association statements on the harms of policing and incarceration.

What we are seeing is more health-care and public health workers recognizing that the illusion of an “improved” carceral institution is just that, and that much more effective interventions can be made for both health and safety outside of these systems.

This is in keeping with the work of advocates and directly impacted people on the ground, who have long recognized the perils of carceral humanism and have worked to stem the tide. In Santa Clara County, California, where elected officials centered the need for a new jail around the “deteriorating mental health infrastructure,” organizer Tina Brown pointed out that harmful “conditions will still exist in a new jail, as it is the culture that is the issue, not the concrete.” Joining the coalition pushing for community-based resources and investments were Stanford family medicine physicians who have similarly seen the inadequate resources available to patients who wind up incarcerated. In Los Angeles, organizers have for years pushed back against the proposal for a new women’s jail as well as a mental health–specific jail. Justice LA has explicitly pushed back against this carceral humanist framing, noting that “a locked treatment facility run by the Sheriff is not a life-sustaining resource of community support but just a façade for a jail.”

In New York City, organizers of the movement to close Rikers Island and not simply replace it with new jails have said that “the larger problem of incarceration” lies at the root of all of Rikers’s troubles, and that the reason for the city’s plan for new, borough-based jails is that “the city is actively planning to incarcerate more people rather than actually addressing the issues that lead to incarceration.” One of the jails on Rikers Island, the Rose M. Singer Center, serves as a facility for women and was initially sold as “gender responsive” and “trauma informed.” Despite this rhetoric, it has consistently reproduced the same violent and abusive conditions of other carceral institutions. In hopes of replacing this jail with a new women’s jail in Harlem, advocates for a new facility have emphasized that one of their goals is “creating a new culture” where “there is justice without punishment.” And some prominent feminists are all in on the idea that there can be a feminist jail in the city.

Yet organizers most familiar with the harms of incarceration consistently reject the idea of a women’s jail being anything but another jail. Instead, they advocate for community-based resources outside of cages. Survived & Punished NY has plainly called the idea of a feminist jail “dangerous,” adding that people, above all, “must be given the option to be free first,” and that everyone, regardless of gender, deserves high-quality care: “No institution that deprives people of their freedom, severs family and community ties, and produces the violent power relations characteristic of carceral spaces can ever be called humane.” And in Georgia, Women on the Rise’s Robyn Hasan has sounded a similar note: “There is no healing inside of any cage.”

To be clear, advocacy to improve the material conditions of those incarcerated today remains critical, but vast resources must not be committed solely with the hope of turning jails, prisons, and detention centers into places of healing. The most effective health intervention for those incarcerated is for them to go home with support. Any recommendations for improving care for the incarcerated should include diversion and decarceration as the top priorities. On the front end, we should also stress the importance of immediately decriminalizing conduct related to poverty, homelessness, and substance use while addressing those needs directly, without resorting to the criminal legal system.

As for us health-care workers, we must organize to confront the deep failures and misplaced priorities of profit over patient health in U.S. health care. In following Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s guidance that “abolition is about the presence, not absence,” we must play a more active role in community-based movements that are imagining and working toward different visions of safety. As a coalition of decarceral public health advocates wrote not long ago, “many in our field are ready to challenge the legacy of punitive policies and envision ways to align public health with abolition through actions, not just mission statements.”

There remains a largely untapped potential for us to embrace a radical politics of change and be a part of shifting the political calculus and public narrative from one of carceralism to one centering care. Ultimately, we health-care workers should reckon with how a profession rooted in doing no harm and providing healing can, in any way, endorse a system rooted in so much dehumanization and violence.

Header image: A group of Atlanta-based health-care workers rally at City Hall on June 7, 2022, in support of the Community Over Cages coalition. (Courtesy image. Image treatment: Inquest.)