EDITORS’ NOTE

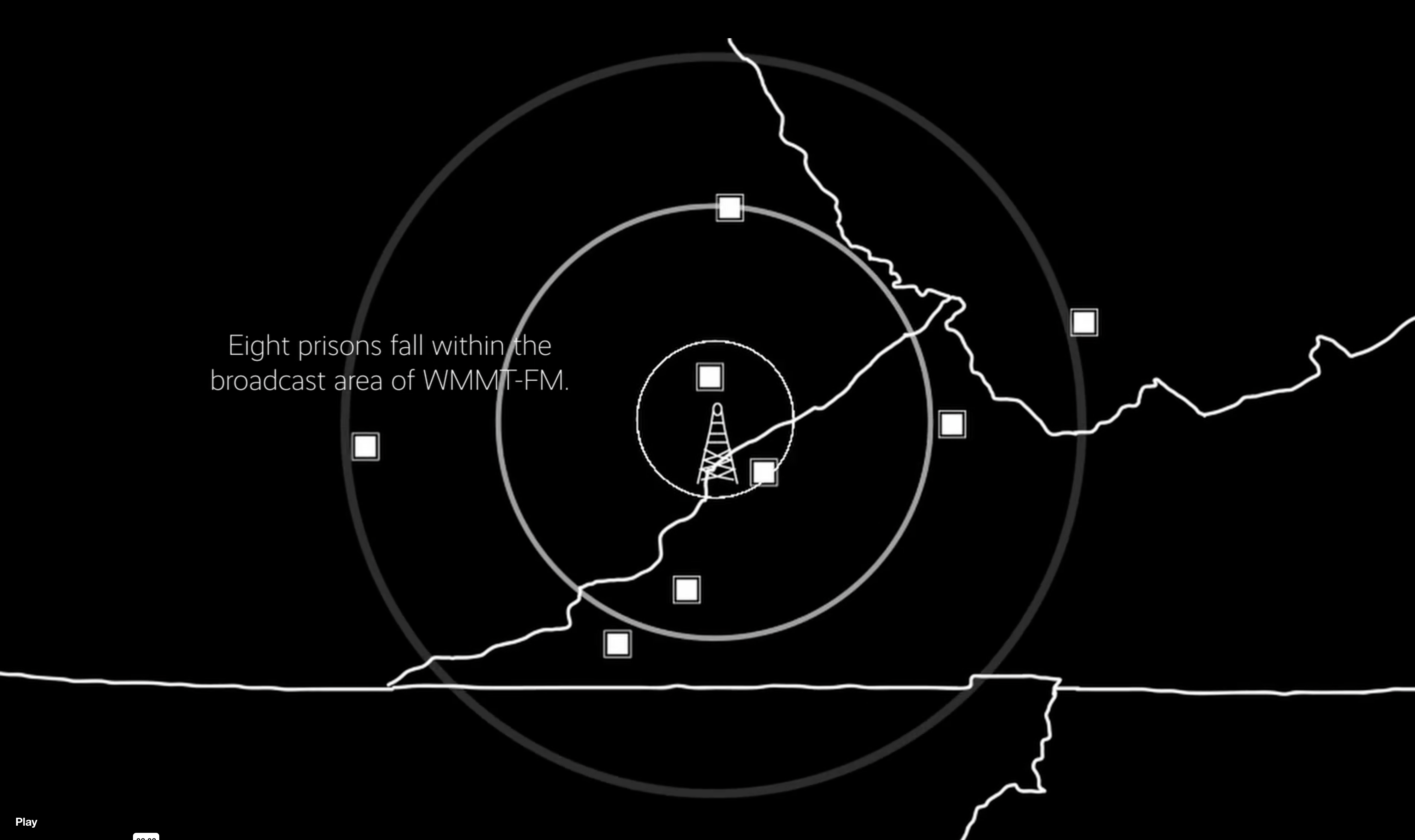

In the past thirty years, Central Appalachia has become one of the most concentrated areas of rural prison growth nationwide. In the late 1990s, Appalshop’s WMMT-FM 88.7, a community radio station in Whitesburg, Kentucky, started receiving dozens of letters with song requests from incarcerated people who were able to receive the station in their cells. By the mid-2000s, eight prisons fell within the station’s local broadcast area.

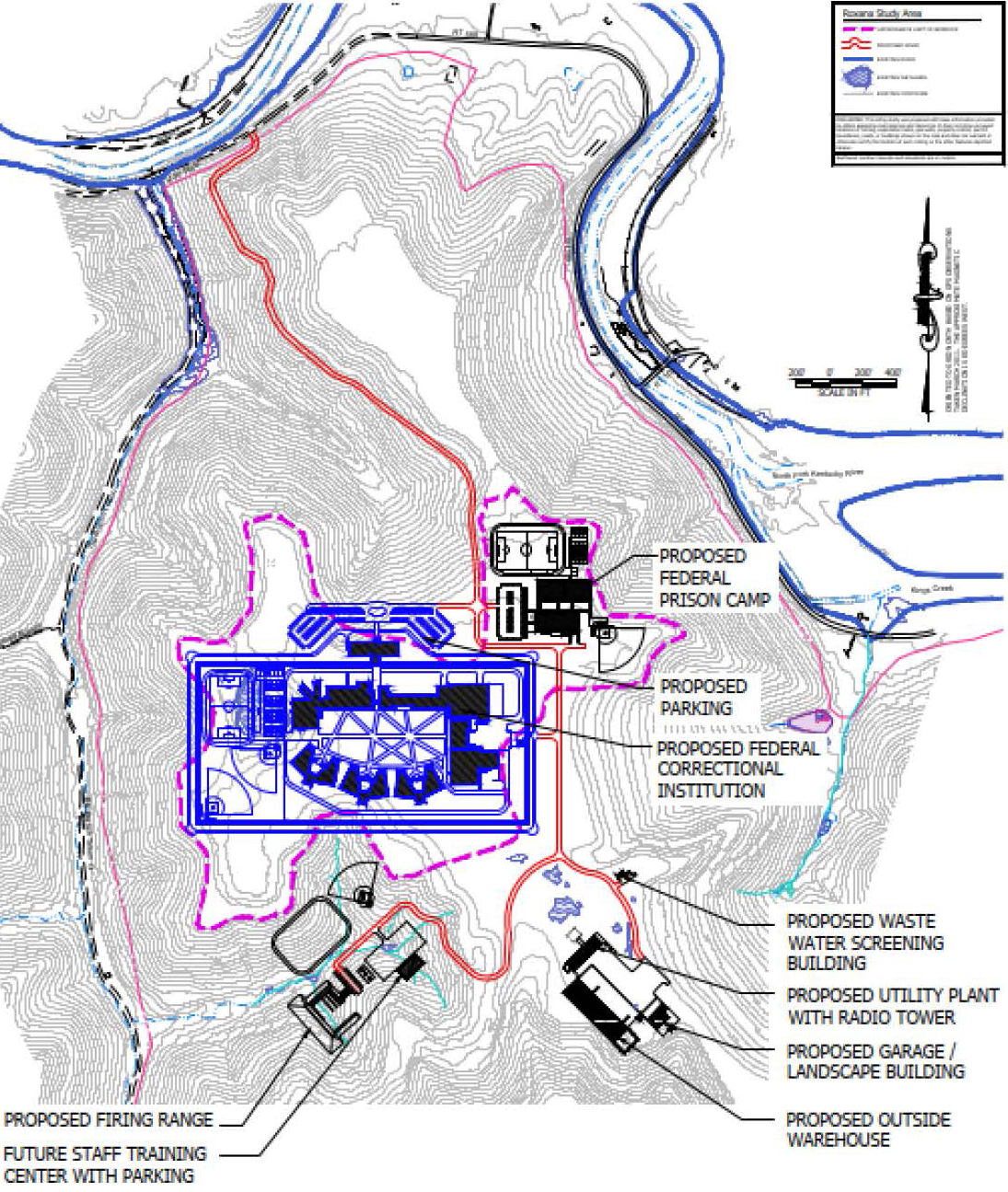

Now there are plans to build another, FCI–Letcher. Inquest’s parent organization, the Institute to End Mass Incarceration, has put its energy behind supporting a campaign, Building Community Not Prisons (BCNP), that is trying to stop this prison from being built. On March 1, 2024, the federal government took a major step toward the building of FCI–Letcher when the Bureau of Prisons (BOP) released its draft environmental impact report for the project. This opened up a required public comment period, one of the only chances the public will have to formally register opposition to the prison.

To underscore to Inquest readers how urgently BCNP needs their help right now, we’ve partnered with BCNP coalition member Sylvia Ryerson to make her award-winning documentary Calls from Home freely available for all Inquest readers to stream from now until April 15, the end of the public comment period. Ryerson has been involved in efforts to stop FCI–Letcher since its earliest days. In the following Q&A conducted by Inquest, she fills in the backstory of the current campaign to stop the prison, and explains why it is so crucial for everyone to get involved during this comment period.

For readers who aren’t familiar with FCI–Letcher, can you catch them up on the history of efforts to stop this prison from being built?

For context, Letcher County is in the far southeastern corner of Kentucky, in the heart of the Central Appalachian Mountains, a region that was once the center of the nation’s coal industry.

Yet coal mining has never brought prosperity to the region, and the fifth congressional district of Kentucky—which is all of Eastern Kentucky, including Letcher County—has long been one of the persistently poorest congressional districts in the nation. This crisis has become even more acute in the wake of the coal industry’s long decline and abandonment of the region, a process which started in the 1980s.

As we have now seen unfold nationwide, this was also the very moment in which our country undertook what Ruth Wilson Gilmore powerfully identifies as the largest prison-building project in the history of the world—a massive prison-building boom that enabled and propelled our current crisis of racialized mass incarceration. Across the nation, prisons were aggressively promoted to rural communities in dire economic straits as a means of economic survival.

This predacious carceral regime hit Central Appalachia with full force. The region is now one of the most concentrated areas of rural prison growth nationwide, and many of these prisons are built on formerly strip-mined or mountaintop-removal-mined land. Eastern Kentucky alone already has more federal prisons than any other federal judicial district in the country. If built, FCI–Letcher would become the fifth federal prison in Kentucky’s fifth district.

This is because congressman Hal Rogers, who has represented the fifth congressional district since 1981, has long used prisons as a means to bring federal money to his district, through his tenure on the House Appropriations Committee. Through his efforts, federal prisons were built in the Eastern Kentucky counties of Clay, Martin, and McCreary in 1992, 2003, and 2004, respectively.

As construction of the 1,600-bed United States Penitentiary (USP) McCreary was wrapping up, Rogers turned his efforts to Letcher County. In 2005, just as he had done in these other counties, he started meeting with the business leaders and political elites of Letcher County, essentially the ruling class of the county, to float the idea of a federal prison. This group of leaders soon named themselves the Letcher County Planning Commission (LCPC), and they have been working with Rogers to bring a prison to Letcher County ever since. The very next year, in 2006, working with LCPC members, Rogers secured $5 million in the Bureau of Prisons’ budget specifically to fund a study on the feasibility of locating a facility in Letcher County.

I think it’s worth pausing here for a moment to think about this extraordinary timeline.

In 2003, 1,300 federal prison beds were filled in Martin County, with the opening of USP Big Sandy. In 2004, 1,600 prison beds were filled in McCreary County, with the opening of FCI–Manchester. Then, in 2005, the very next year, Rogers began working with local elites to bring what was then proposed as USP Letcher, a 1,200-bed maximum security federal prison, to Letcher County. Of course, “prison beds” is a euphemism for incarcerated people in the discourse of rural prison building. And in the space of just a few years, 3,000 people were sent to new cages in the coalfields—to riff on the title of Judah Schept’s brilliant book Coal, Cages, Crisis—in the name of economic development.

The plan was obvious and straightforward: Once USP McCreary is done, we’ll build another one in Letcher.

But this is not what happened. Things have not gone according to plan for Rogers in Letcher County. Now, in 2024, he is still attempting to build this prison, but has not yet succeeded.

Why hasn’t this gone as planned for Rogers?

To me, this is the most interesting and exciting question of all. As outrageous as it is that we’re still having to fight this prison after twenty years, the reason we’re still fighting it is because we’re winning.

The proposal for USP Letcher gained significant momentum in 2016, when $444 million was allocated for its construction in the FY 2016 budget. Then, after three years of visionary and relentless organizing—led by local landowners, incarcerated people, and regional and national abolitionist organizers and lawyers—the project was defeated in 2019, in a historic win. For the first time in the bureau’s history that we know of, the BOP rescinded its decision to build the facility after it had completed the required environmental review process and an official record of decision (ROD) to proceed with construction had been made. This was an incredible victory, and it was the direct result of strategic abolitionist organizing to exploit carceral contradictions at the highest levels of the U.S. government.

Yet sadly, as we know well, just as carceral hegemony is never a complete project, neither is abolitionist victory. Even after the decision to build was withdrawn, Rep. Rogers fought to keep the funding for it—which has now grown to over $500 million—allocated in the federal budget.

Notably, both the Trump and Biden administrations have proposed rescinding the funds for this prison, and even top officials of the Bureau of Prisons have gone on record to say that this new prison is not needed and the funds could be better spent, citing the declining federal prison population, aging BOP prisons that are in dire need of costly repair, and extreme staffing shortages BOP prisons are facing nationwide. Yet due to Rogers’s outsized influence in Congress, half a billion dollars have remained allocated in the federal budget for a prison that the BOP does not have the approval or desire to build.

Meanwhile, the situation in Letcher County has become even more dire. The coal industry has continued to depart, leaving behind a ravaged landscape of untold human and environmental costs that continue to be unearthed.

In late July 2022, Letcher County was hit by catastrophic floods, exacerbated by the lasting impacts of surface mining. The flooding killed 45 people and destroyed over 9,000 homes across 13 counties. And then, on September 28, 2022, two months after the floods, when everyone was still in the midst of this emergency situation and thousands of people across the region remained houseless and displaced, the federal government posted a “Notice of Intent To Prepare a Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the Proposed Federal Correctional Institution and Federal Prison Camp in Letcher County, Kentucky” in the Federal Register.

Everyone who was a part of the last fight couldn’t believe it. It was just so appalling and outrageous for this prison to be proposed again, in the midst of this terrifying and devastating tragedy—when hundreds of people in Letcher County had just lost everything, and didn’t even know where they were going to sleep that night, let alone have time to think about this. And that, in the face of the most severe housing crisis in the history of Eastern Kentucky, Rogers would again propose spending more than $500 million on human cages that no one wants or needs. It was overwhelming. As BCNP member Artie Ann Bates put it best: How can you fight a prison when you’re living in a tent?

I was actually at a flood recovery conference in Hazard, Kentucky, the weekend we got the news that they were going to try again to build the prison. And those of us who had been a part of the last fight, we all just kind of looked at each other and shook our heads—like, OK, here we go again. But there wasn’t a moment of hesitation. The fight was back on.

Your short documentary Calls from Home is based, in large part, in Letcher County. Could you talk about your connection to Letcher County, and what led you to make this film?

I first came to Whitesburg, which is the county seat of Letcher County, for a summer internship at Appalshop’s community radio station, WMMT-FM, in the summer of 2008. I’m originally from Cambridge, Massachusetts. I had just finished my junior year of college, and a large part of what drew me to Letcher County in the first place was some of the incredible work that was happening at Appalshop at that time, against the U.S. prison–industrial complex. I had just read Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California in a seminar on the history of the U.S. prison system, and Gilmore’s work made it so clear to me that prison building is a geographic problem—what Gilmore calls “a spatial fix.” So to confront this system, we have to work together from multiple different geographies. Yet at that time, Appalshop was really one of the only rural organizations in the country doing work on the issue of mass incarceration.

This work started over the airwaves of WMMT-FM. In the late 1990s, two identical supermax Virginia state prisons were built right across the state line in Wise County, Virginia, which is adjacent to Letcher County, and both fell squarely within WMMT’s listening area. Soon people incarcerated in these new prisons, who were mostly not from the region and very far from home, started writing letters into the radio station with song requests, personal stories, questions about the area, and descriptions of horrific abuse that was happening inside. They were seeking help, connection, and information—desperately trying to connect with the world outside and make sense of where they were.

At the same time, they faced astronomical phone rates as they tried to stay in touch with their families back home. Prison phone rates in Virginia at that time cost about $7 for a twenty-minute call. Families were paying $400 a month in phone bills, just to maintain a bare minimum of communication with their incarcerated loved ones.

Building from the relationships that the people incarcerated established with WMMT DJs over the airwaves and through letters, people incarcerated started sharing the station’s toll-free number with their families, encouraging them to call in to leave song dedications and messages over the air, to circumvent the exorbitant cost of prison phone calls. Rooted in Appalshop’s long history of making media to support social justice organizing in the region, the radio station kept the phone lines open for these calls, and, importantly, from the very start saw this work as aligning with its core mission—which is to reflect on air the community it serves. In doing so, it was recognizing all the people incarcerated within its listening area as a part of the community, in opposition to the logics of separation on which this carceral regime relies.

Once these logics are transgressed, their hold is loosened. Quite simply, people got to know each other over the airwaves, and out of this, a whole body of work at Appalshop emerged on the issue of mass incarceration. This included the Thousand Kites Project as well as the 2006 documentary Up the Ridge, directed by WMMT DJs Amelia Kirby and Nick Szuberla. That film focuses on the construction of, and deadly abuse within, Wallens Ridge State Prison in Wise County, Virginia, home to many of the listeners of the Calls from Home radio show.

This groundbreaking work and more drew me to Appalshop and WMMT-FM. I came back the following summer to conduct research for my undergraduate thesis on prison expansion in Central Appalachia, and then after graduating from college in December 2009, I returned to work at Appalshop full time, first as an AmeriCorps VISTA member and then as radio station staff.

During these years, plans for USP Letcher continued to move forward, almost entirely behind closed doors. But every time another hurdle was passed, it would appear on the front page of the Mountain Eagle, the local newspaper. And so I started to see in real time how this prison was being promoted to the community as a means for getting desperately needed new infrastructure and economic development. The community was being told that, in the wake of the coal industry’s decline, this new federal prison would bring hundreds of well-paying jobs with good benefits, that it would “fuel the economy” for decades to come, making it possible for young people to stay there rather than having to go elsewhere for opportunities.

By then I had become a regular DJ for the Monday night Hip Hop from the Hill Top/Calls from Home music and call-in show. And it just became jarringly and viscerally apparent to me how all the voices and experiences of the people I was coming to know over the airwaves—the grandmothers, girlfriends, kids, uncles, and brothers calling to leave shout-outs to their loved ones incarcerated extremely far from home—were entirely absent from this local reporting; it was solely a conversation around economic development and jobs.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

I also knew that none of the promises being made were true. There’s now an abundance of regional and national research that disproves the argument that is always advanced for building rural prisons, which is that they’ll be a source of jobs and income for economically depressed areas. Numerous studies have found that not only do prisons not bring the purported economic benefits to struggling rural communities, but they can in fact have a negative impact on the local economy, particularly when built in persistently poor places with high levels of poverty and unemployment.

Local people are mostly ineligible to receive any of the new jobs. The requirements for getting these federal prison jobs are made clear only very late in the process, once the prison’s construction had already begun, and federal requirements for various kinds of preemployment screening disqualify most of the county’s unemployed and underemployed. This is very important, as it shows how prisons are not conceived of or designed to be a rural jobs program to meet the urgent needs of the community, they are simply sold as one. They are what I call a federal jobs program with no guarantee of jobs.

Prisons are antithetical to the kinds of job training and work opportunities Appalachian communities need and deserve right now, as the region remains in the midst of a massive economic transition, and is still in the throes of an addiction epidemic that was fueled by the opioid industry—leading to skyrocketing incarceration rates within the region.

Residents of Letcher County deserve purposeful and meaningful work that builds from the history of the region and the skills people already have. Not the promise of jobs that the majority of the population is in fact ineligible for, and if gotten, take a devastating psychological and physical toll.

All this to say that, in addition to hosting the radio show, I was also a reporter for the station and trying to figure out how to intervene in this narrative of jobs, jobs, jobs.

And I soon became frustrated by the limits of this debate: Will the prison bring jobs, or will it not bring jobs? I remember one conversation I had with one of the members of the Letcher County Planning Commission, the group working to bring the prison. I told him about my research from these other counties, and how few of the jobs actually materialized. He said, “Well, even ten jobs is better than no jobs.” I didn’t know what to say.

Within these terms, the jobs argument is a losing argument. If the math is 1,408 people in prison for 10 jobs, something is so terribly wrong that an economic analysis alone can’t change the conversation.

We need to entirely break open the terms of this debate: What are these jobs? What impact will they have on the people who have them? And their families? Are these really the jobs we want to be offering to Letcher County youth, as the primary motivation for them to go on to get a higher education?

And at the same time, what will this prison mean for the people who are incarcerated in it? As a federal prison, this facility will incarcerate people from across the entire United States. Letcher County has no bus station, no train station, no public transportation access at all, and there is no airport within a hundred miles. It will simply be impossible for most families to get to this prison to visit their loved ones inside. The impact this would have on children with incarcerated parents at this facility would be devastating.

And Letcher County is 97 percent white. The federal prison system, like our entire criminal legal system, grossly over-incarcerates Black and brown people from hyper-policed urban communities. This prison would inevitably perpetuate the racial violence that is endemic to the entire U.S. prison system.

Decades of activism and scholarship have made clear how the U.S. prison–industrial complex puts differently dispossessed communities into relationship—an inherently antagonistic and predatory relationship within the zero-sum logics of racial capitalism. We are essentially being told, again, that in order for one community to be lifted out of poverty, other communities must remain impoverished. Yet, in fact, we know that rural prisons simply work to consolidate crises and keep them out of sight.

To confront this system we need to build new relationships across the multiple geographies of carceral dispossession. The public airwaves of WMMT-FM created a forum where this could begin to happen.

So, to get back to your question, I wanted to make a film that makes it impossible to ignore the voices and experiences that are being excluded in this conversation, and, also, to try to show the work that these airwaves are doing, in creating a space for us to come to know each other outside of the dominant carceral logics and stereotypes that saturate our society.

Everyone who is featured in the film I came to know through hosting the radio show. These relationships are precious and invaluable; they form the foundation of our commitments to one another.

And I think these connections, forged over the airwaves, are a huge part of why things have gone so very differently for the BOP in Letcher County.

What does this second iteration of the campaign to stop FCI–Letcher look like? And where do things stand right now?

When it was announced a year and a half ago that the BOP was restarting its efforts to build a prison, now renamed FCI–Letcher—the proposal has changed from a maximum- to medium-security prison—a new coalition quickly coalesced, called Building Community Not Prisons.

The coalition includes people in Letcher County, longtime Central Appalachian organizers, national environmental and abolitionist activists, and lawyers (including from the Institute to End Mass Incarceration, which publishes Inquest). This coalition has the benefit of building from all the amazing organizing that happened in the first campaign, and is leveraging every possible angle by which to oppose this prison and demand better for all communities. We are fighting for the complete rescission of these funds from the federal government, so that this prison is not built in Letcher County or anywhere, and for these half a billion taxpayer dollars to be reinvested in the public goods that actually work to keep communities safe—like quality and affordable housing, health care, education, public transportation, and so much more.

This coalition is already changing the terms of the debate, and we have a wealth of experience and scholarship to build from. And I want to share two core, interlocking frames that I think we can use in this moment, as we work to wholly refuse this prison and demand better.

First, a system that generates profits by transfiguring people into “prison beds” cannot be solely considered or confronted within the politically neutralizing discourse of “economic development.” Rural prison-building is not, and really was never intended to be, a form of economic development for the communities that need it most. It is not a jobs program. It is a system of racial apartheid and family separation that enriches the already wealthy.

Second, not only do rural prisons not bring the promised jobs, but they perpetuate and deepen the very processes of rural dispossession and extraction that made these communities so desperate for a prison in the first place. These prisons do this by further entrenching existing hierarchies of consolidated wealth and power, absentee land ownership, and antidemocratic governance—the very structures that have long been at the root of Appalachia’s impoverishment.

Importantly, right now, we’re at a really crucial inflection point in the campaign’s work—a pivotal moment in which we can all intervene in this conversation. On March 1, the BOP released its Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) as required through the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). This initiated a required public comment period that is open until April 15. This is one of the very few moments in this whole process in which public comment on this prison will be officially accepted and documented in the public record.

Right now, the Building Community Not Prisons coalition is asking everyone who cares about this to submit a written public comment opposing this prison.

The DEIS absurdly states that this prison has “consistent, continuous, and unwavering support.” We are asking everyone to go on record to help us show that this is not the case at all! That there are thousands of people who don’t think this prison should be built and that we need to invest our federal taxpayer dollars in building community not cages.

Once the environmental review process is complete, we predict that the BOP will deem this a good site to build a prison, at which point litigation is expected to follow. This comment period is also necessary to create standing for future litigation. We have an incredible team of legal experts and lawyers in the coalition who are already thinking through every legal recourse we can use to oppose this. The idea is to challenge this prison on every possible front—its purported economic impacts, its environmental impacts, its racial impacts, its social impacts, its public-health impacts. We’re doing this for all those inside and outside its walls. We all stand to be impacted by this. And so we hope everyone will join us in building this record of dissent.

Ryerson’s award-winning short documentary Calls from Home is freely available for all Inquest readers to stream from now until April 15, the end of the public comment period. Follow this link to watch.

Header image: An aerial view of the WMMT radio tower, as depicted in the Calls from Home film. Image courtesy of the author and Working Films.