While I was doing time, the Federal Bureau of Prisons changed their smoking policy and the prison where I was locked up banned cigarettes. Of course, commissary first sold off all the remaining cartons of coffin nails, and the looming ban triggered a frenzied rush to stockpile. Incarcerated tobacco enthusiasts had one month to smoke their brains out, and then cigarettes became contraband.

This had a big impact on the culture of the unit where I lived, a minimum-security prison camp where women had a lot of access to the outdoors. Some of the women I was close with were addicted to nicotine, and many more would smoke out of boredom or to relieve the abundant stress found behind prison walls. The hunt for spots to hide cigarettes and — more challenging — spots to actually smoke them was matched by the hunt of COs on the prowl for violators.

This cat-and-mouse game, one with serious consequences, affected all of us whether we were holding contraband or not. I remember rounding the corner of an outbuilding to find a huddle of nervous women sucking down smoke. “Don’t burn the spot, Piper!” was their entreaty, and while I was incarcerated I would never, ever have done so, for reasons both practical and principled.

The need to keep secrets, hold confidences, and protect the spot is extremely powerful in prison, a place of constant threat and surveillance from many quarters. The need to tell the truth in the face of these pressures creates a unique conflict for incarcerated and also formerly incarcerated writers. Truth can hurt, and prisons are already bottomless wells of pain and trauma. I think writing from prison or about prison creates a moral demand to counter that maw of suffering, even as you are bearing witness to it.

When I write about prison, and when I teach writing to incarcerated men and women, these quandaries are often top of mind and discussed with intensity. The judgment of the writer carries great value for their reader, but judging others can be a queasy business for criminalized people. Some of the best writing my incarcerated students have done puts people they know out on front street: a parent whose choices were, mildly put, flawed; a powerful but disturbing characterization of a cellie or a prison neighbor; a codefendant who fucked up big-time.

A good story has people vividly rendered, their powers and weaknesses revealed, the attractions and repulsions of their presence strong enough to be felt by the reader. Paper-doll heroes, villains, and sidekicks are boring. So is work that is abstract and oblique to the point of meaninglessness. When I wrote Orange Is the New Black: My Year in a Women’s Prison, I tried to write about the people I encountered while incarcerated as freely, honestly, and specifically as I possibly could in the first draft. Revision allowed me to revisit my pages with conscience and discretion. I wrote about women whom I loved with abandon, men I detested from my gut, and some people who evoked more conflicted feelings.

Any writer of personal stories will surely think about, and perhaps worry over, how the real people who populate those stories — whether they are termed “fiction” or “true” — will feel about their portrayal. One of the values of revision is the opportunity for the writer to reflect on where that portrayal came from, within them. Being honest will put your own racism, misogyny, homophobia, and other ignorances front and center, so take the opportunity revision offers to wrestle with and question your own received truths.

For incarcerated or formerly incarcerated writers, these dilemmas take on heightened and complex calculations. One of the most compelling ingredients of writing is conflict, and incarcerated people are pretty much guaranteed to have that in spades. Whatever the facts of their case, innocent or guilty, they are in conflict with the state, and that conflict will be personified: in their jailers and overseers, their bunkies or cellies, the other prisoners in their unit, their loved ones whom they are separated from, perhaps now-distant victims whom they have harmed.

There are two practical concerns that arise while writing truthfully: protecting yourself, if incarcerated, and protecting other people.

There are two practical concerns that arise while writing truthfully: protecting yourself, if incarcerated, and protecting other people. On day 1 of a writing class in a men’s state prison, I was asked, “Are the cops going to read our writing?” Fear of confiscation may require you to write a version of prison life that changes certain facts, such as names and other identifiers. Fear of exposing others to harm, or re-traumatizing people, will also guide your hand.

Incarcerated people also carry with them the conflicts they survived before being locked up. There is a likelihood of heightened, dramatic conflict in a person’s life on the outs. People who are in prison or jail are often among the most marginalized people in society, and existing on the margins is a struggle that includes scarcity and pain. When I teach in prison, we work on stories with many kinds of conflict: person versus person, person versus nature, person versus society, person versus fate, person versus self. These springboards get you into the pool where your lived experience with other people swims alongside your creative aspirations. Your creativity will make truthfulness possible, even as you take seriously a responsibility not to harm others. The best advice I can give is to write about people with love, even when their actions are wrong. This is easier said than done, but it will result in your best work.

When it comes to characterization, the prison writer must face the antagonist. This is true in self-characterization, and we contend with it in our portrayal of others. I have students who have written tenderly about a parent in response to one writing prompt, only to share a terrifying story of abuse and neglect a few weeks later. Same parent, both stories are true. Even the most flawed people are multidimensional, and those who have impacted our lives deserve full consideration in our writing. Blind spots around race, class, gender, and sexuality exist for all of us, and when we dehumanize others in our storytelling, we only diminish our own humanity in the mind of our readers.

Every writer has to fantasize success — whatever that means to them — or we would never finish anything. I realized shortly after the publication of my book that the story no longer belonged to me, other than in the literal sense of copyright. When the ink was dry and I gave the story over to the reader, it now belonged to them. And readers loved the other women in Orange Is the New Black, so much that the story took on entirely unique and expanded meaning in adaptation. I heard from many of the women portrayed in the book, and only one objected to her characterization (and we are still friends). A close pal told me, “I loved this book so much I didn’t want it to end,” which was hilarious given how much we wanted to get out of prison. Another woman, whom I bumped into on the street, offered a compliment with a cooler temperature. She didn’t say she liked the book; she simply said, “I’m glad you wrote it.”

What’s the intention of your writing? If you periodically return to this question it will help you make humane choices about your portrayals of other people. For what you keep private, there is full license and in fact necessity to put down the unvarnished truth. When you are writing for publication, remember what your primary goal is: Is it to entertain, to bear witness, to educate, to persuade toward action? What you want to accomplish will determine how you populate the world you create, no matter what form your writing takes.

I set out to write about my experience in prison with an optimistic hope that if readers imagined themselves in the shoes of the women I portrayed, then maybe they might think and feel differently about mass incarceration.

I set out to write about my experience in prison with an optimistic hope that if readers imagined themselves in the shoes of the women I portrayed, then maybe they might think and feel differently about mass incarceration. I certainly conceived my memoir as a fuck-you to the Bureau of Prisons, the people who run it, and the feds more broadly. My task was to draw a reader who thought of themselves as an upstanding, law-abiding citizen into that repudiation of a system they may have seen as their protection.

If you want to write unforgettable stories and share ideas that will change your readers forever, you better get ready to burn the spot. I remember one of my codefendants, my crimeys, counseling me almost 30 years ago: “Practice lying. Lie all the time, even when you don’t need to. Get good at it.” But even a lie tethers back to some sort of truth, and fiction is grounded in facts. Many incarcerated people are incredibly good storytellers, whether their medium is the spoken word, prose, or playwriting, and I’d argue passionately that in writing about other people you must practice telling the truth. You can change the names. You can tweak identifying features to a certain extent, but you have to make those people palpably real to your reader. They are worthy of your truth.

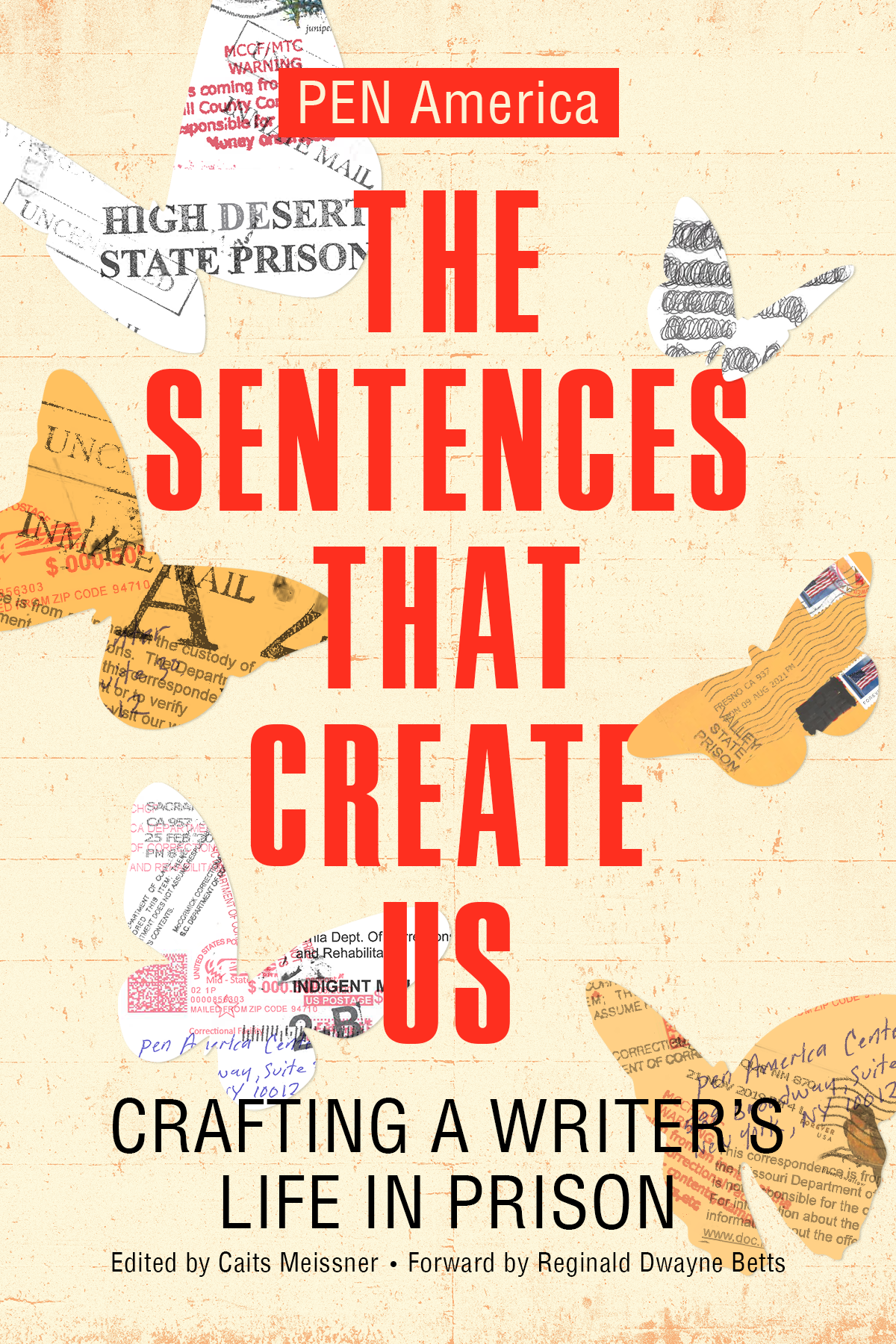

Excerpted from The Sentences That Create Us: Crafting A Writer’s Life in Prison by PEN America, edited by Caits Meissner (Haymarket Books). Copyright (c) 2021 Caits Meissner. Used by permission of Haymarket Books.

Image: Jacqueline Brandwayn/Unsplash