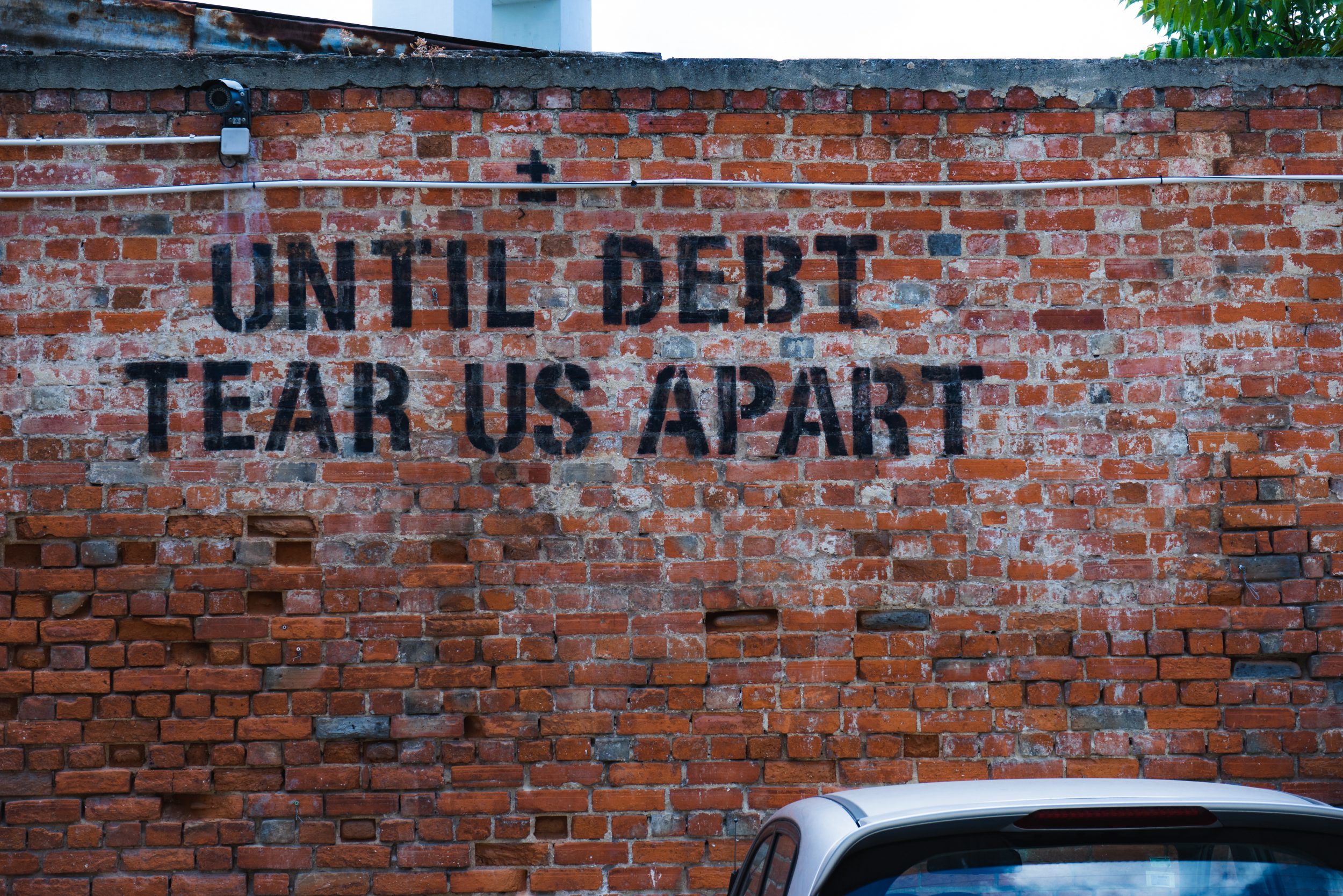

As the United States grapples with how to undo and repair the far-reaching harms caused by mass criminalization and incarceration, the elimination of legal debt offers the chance to undertake a relatively small change that would have an immense impact. People involved with the criminal legal system routinely hold multiple debts attached to their criminal convictions, even if they have already served time or completed probation. There are many costs associated with a criminal conviction, but court costs are some of the most common. In many states the revenue generated by court costs goes directly to states’ general funds, thereby functioning as a regressive tax on poor, Black, Latinx, and Indigenous peoples. And while it is technically unconstitutional to incarcerate people for unpaid debt, judges can still imprison people for “willful” non-payment.

In 2023 a decades-long process to enact this change in Rhode Island culminated in the elimination of millions of dollars in court-related debt, as well as successful legislation to ensure that low-income people do not become indebted to the courts. We were involved in manifesting this change, and in this essay we share information about how we were able to achieve success, in hopes that advocates in other states may find inspiration in our efforts.

In the wake of George Floyd’s and Breonna Taylor’s 2020 murders by police, the Rhode Island Judiciary created the Committee on Racial and Ethnic Fairness in the Courts with the goal of improving equity in court outcomes. Our nonprofit, the Center for Health and Justice Transformation (CHJT), focuses on the public health implications of legal system involvement, and we became involved in the community engagement portion of this work.

In connecting with judges, we found some encouraging support for the idea that court fines and fees are a racial equity issue, building off of an already existing precedent for eliminating them. In 2008 the state legislature had passed a law allowing judges to waive and remit court costs for people who could show an inability to pay—though, granted, use of the law had been inconsistent. Predating this law was years of groundwork laid by Open Doors, a local reentry and housing organization, arguing the disproportionate impact that court fines had on low-income Black and brown people.

Equipped with Rachel Black’s Brown University thesis on court debt and indigency, as well as a College Hill Independent investigative report, the CHJT held a virtual community forum in partnership with the Committee on Racial and Ethnic Fairness in the Courts. At the forum, participants confirmed that they did not understand what court fines were and expressed their confusion with the opacity of the court system. Many felt that their court debt “chained [them] to the system.”

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

After this forum, the CHJT began to have smaller meetings with public defenders, attorneys, and grassroots advocates to understand how ability-to-pay hearings occurred (at the time, the courts were not allowing the public to sit in on hearings due to COVID-19). One of the emerging themes was that people simply did not know that they had the right to an ability-to-pay hearing and therefore did not know the language they could use to advocate for themselves. However, after continuing to speak with impacted Rhode Islanders about the inaccessibility of the courts—and the fear tied to returning to court—we found that simply creating an advocacy sheet for court users would not be enough.

In order to continue these discussions with the judiciary while also figuring out how to bring about system-level change, we hosted an in-person roundtable at the United Way of Rhode Island in March 2021. We invited community members as well as judges. At this roundtable, judges were given the opportunity to ask and field questions about the ability-to-pay process and why court debt was assessed. Importantly, there were several questions about the process that judges either did not know the answer to or had different processes for handling, shining light on the difficulty for individuals to understand and navigate the system they were indebted to. Even judges struggled with their confusion about aspects of it, it turned out.

The roundtable made evident that the ability-to-pay remediation process was broken and inadequate. We conducted policy research to understand how other states have approached court debt reform, and we published a brief making a public health argument for eliminating court debt altogether.

The outcome of these conversations and the brief was remarkable: The Superior Court judges who had attended the roundtable approached the CHJT and asked us to partner with them to host community ability-to-pay hearings. These hearings would mimic Rhode Island’s Operation Stand Down, a partnership between Rhode Island’s Veterans Court and service providers to give support to veterans involved in the legal system, directly in the community.

Thus, in November 2021, we began hosting monthly Community Superior Court Cost Review Hearings. These community-based hearings simplified an otherwise confusing process: Individuals with outstanding court costs could have a virtual video meeting with a judge, who on the spot assessed their ability to pay and discharged their debt as appropriate. CHJT volunteers were on site to help participants fill out financial statement forms as proof of their inability to pay, and each host site shared information about their reentry services. Having local organizations host the hearings reduced stress for participants. Many had been traumatized by previous court appearances or feared that going to court would mean facing warrants. Furthermore, we worked with the court to ensure that there was no police presence at our events.

Participants owed an average of $3,000. The hearings served 688 people and eliminated $2.3 million in debt.

In responses to short-form surveys, participants emphasized how having their debt remitted created a newfound sense of optimism and hope. “Now I feel free. I never knew when I would feel free,” a participant shared with us. Another participant remarked: “Before it was really hard making sure I had the minimal amount to pay my fines on top of all my other expenses. . . . Now I can apply money to other things, to moving forward with my life. I can invest in my life again.”

Judge Luis Matos, associate justice in Rhode Island’s Superior Court and member of the committee, was the primary judge presiding over these hearings. “I’ve seen how fines and fees can break a person’s spirit when they are simply trying to deal with life’s challenges,” he said. “It just seems like an unfair and unnecessary challenge that is separate and, frankly, contrary to the pursuit of justice. At the end of the day, you want everyone to have a fair opportunity to pursue a good and honest existence.”

CHJT’s goal with the community events was to address the legacy of court debt afflicting individuals, but we continued to have conversations with members of the judiciary on long-term system-level change. At the start of the 2022 legislative session, the judiciary submitted legislation that strengthened the 2008 bill by guaranteeing ability-to-pay hearings for indigent individuals. And, in a new provision, it eliminates court fines and fees for individuals who serve sentences longer than thirty days.

In June 2023, we were able to conclude our community hearings. This was thanks to administrative changes spearheaded by the Superior Court. These new policies enable individuals to simply submit an inability-to-pay application to the courts via mail, fax, or in person to initiate the ability-to-pay process without having to appear in court.

Though our events largely served Black and brown Rhode Islanders living in or near poverty, court debt impacts working families of all demographics. A debt of even a few hundred dollars is, for many, a burden if not an impossibility to pay off. Over 60 percent of Americans are living paycheck to paycheck, yet systems continue to criminalize—and profit off of—poverty at every chance. And considering that nearly half of children in this country have parents with some form of legal system involvement, and thus likely are saddled with court debt, the harm caused by these monetary sanctions is not limited to the individual with the debt.

Our community cost review events, coupled with policy changes, have provided a possible roadmap for financial freedom and independence from the criminal legal system altogether. Mass incarceration perpetuates significant harm on individuals, their families, and broader communities. The court system is a powerful actor within the carceral complex, and possesses the power, independent of prisons, to destabilize people’s lives. Widespread elimination of court debt is an important mechanism for untangling people from the legal system’s web and promoting health (financial, familial, mental, and physical) within communities.

Image: Ehud Neuhaus/Unsplash/Inquest