I am standing in an air-conditioned auditorium thinking about Michelle Cusseaux and the countless other Black women killed by the police whose deaths “no one was paying attention” to. My audience on this balmy spring day is mostly made up of public interest lawyers, students, and faculty. I am remembering the courage that Michelle’s mother, Fran Garrett, exhibited after Phoenix police killed Michelle in her own home. Michelle’s story, like those of too many others, would have ended when Sergeant Percy Dupra stole her life had she not been born to a tenacious mother who refused to let her daughter’s name be forgotten.

Fran was determined that her daughter’s life and death would not be reduced to obscurity, another statistic that no one counted. Michelle was killed just five days after a cop gunned down Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. After seeing the community protests taking shape there, Fran decided to march Michelle’s casket to Phoenix City Hall. In this brave act of protest, she joined a powerful tradition of Black women resisting and denouncing the state violence that directly threatens them and all too often destroys their families.

Fran’s march to the Phoenix City Hall was a flare in the night. Fran’s radical act—literally placing her daughter’s casket at the door of municipal power—not only demanded that Michelle be seen but also rendered visible the police killings of other Black women. The sorrowful procession of Michelle’s coffin to city hall left a searing image that spoke to the many ways in which Black women’s fate has been left in the hands of police while their stories have been marginalized and sometimes erased.

While Brown’s killing justifiably sparked a wave of nationwide protests over lethal police shootings of Black men, the killing of Black women such as Michelle had yet to be memorialized in widespread activations and denunciations. Fran offered a powerful and moving witness to the fact that Black women were also losing their lives in circumstances that spoke to the disregard of Black life and family bonds. There was no sound reason for their stories to be banished to the shadows of our collective consciousness, mere afterthoughts in the litany of savagery that has come to constitute anti-Black state violence.

Fran’s act reminded us all of the obvious fact that slain women’s mothers don’t grieve for them any less, their children don’t cry for them any less, their siblings don’t mourn them any less, and we should not protest their killings any less than we do the killings of their brothers, fathers, and sons.

Six months later, as I look out at the audience, I wonder who among them will know Michelle’s name. Would they know of any other daughters who were stolen like Fran’s was? Or was the erasure of these horrific losses difficult to interrupt because of the reflexive ways that the very notion of anti-Black police violence defaults almost exclusively to our endangered sons? To make the patterns of erasure visible—and audible—I invite the audience to join me in doing something new. I ask those audience members who are able to do so to stand. I tell them, “When you hear a name you don’t recognize, take a seat and remain seated.” I promise to invite the last person standing to tell the seated audience what they know about the person whose name no one else recognized.

Then I call out the names, slowly, deliberately, and loud enough for even those seated at the very back of the auditorium to hear: Eric Garner, Mike Brown, Tamir Rice, Philando Castile, and Freddie Gray. I’m always a bit surprised when one or two people don’t recognize even those first few names, but fewer than a handful have taken their seats by the time I lift up Gray. The vast majority of people recognize these men and know the common risks that link their fates: they are Black and did not survive an encounter with the police.

I pause for a moment and ask the audience to look around. The room is quiet and still. People take in what they have demonstrated: group literacy about the vulnerability of Black people to police violence. At the moment, it seems a completely obvious reading of social knowledge that is minimally necessary to ground any conceivable collective action.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

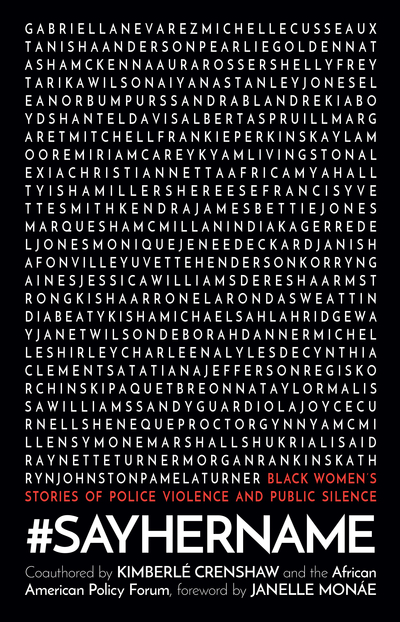

I continue. I say “Michelle Cusseaux.” And then comes that whoosh of dozens, sometimes hundreds, sometimes thousands of people taking their seats. It is the sound of silence. The sounds of people taking their seats mount as I continue the roll call: “Tanisha Anderson, Aiyana Stanley-Jones, Kayla Moore, India Kager, Shelly Frey, Korryn Gaines.”

One person is left standing after Kager, but I continue anyway so people can hear more names. Yet the point still hangs over us. The silence about Black women who have been killed by the police has distorted our collective capacity to respond. We cannot address a problem we cannot name. And we cannot name it if the stories of these women are not heard.

The African American Policy Forum’s (AAPF) #SayHerName campaign began in earnest against the background of this profoundly disturbing reality: The deaths of Black women who were killed by the police barely registered a blip in the national news. Fran and so many others were grieving and protesting the loss of their loved ones all too often without the support and recognition of their communities, the media, and sometimes even their own families. Something had to change.

If the conditions don’t fit the prevailing frames of reference, it is extremely difficult to draw attention to an unfolding crisis. From the outset, the #SayHerName campaign has sought not only to recognize and memorialize the deaths of Black women killed by police but also to confront, contest, and dismantle the interlocking systems of state power that continue to routinize and normalize those killings. The deceptively simple imperative to “say her name” has been a critical component of that work that operates on different levels.

On one level, the directive to say her name is a plea for equality of attention to ensure that violence against Black women be treated with the same urgency and awareness as violence against their brothers. But even the simple act of name-saying raised a host of challenges involving the actual capacity to do so. So many names were unknown because of the same imbalanced dynamics of gender recognition that called the #SayHerName project into being in the first place.

By uncovering these neglected stories and giving them names, faces, and personal histories, we sought to reverse this long-standing pattern of malign neglect in real time—to restore these overlooked victims of state violence to a position of honor and equity in spaces where lost lives are being protested. That seemingly straightforward imperative required more than a demand. We needed to explain just why and how Black women victims of state violence had, for generations, not played a significant role in the narrative of the lethal policing of the Black community. That realization opened onto another one: We had no readily familiar ways of imagining the risks associated with Black women’s encounters with police.

Vulnerability to police violence is an experience girls and women killed by police share with Black men. What they do not share in common with their fallen brothers is the same public attention, communal outcry, or political response. This is not to say that Black men have received too much attention. They have not. It is to say that while Black male encounters with state violence have served as a battle cry for contesting police power, Black female encounters—with few exceptions—have not. The erasure of Black women, regardless of the circumstances, speaks to the consequences of the deaths occurring outside of the readily available narrative of anti-Black police violence.

The #SayHerName campaign was launched to fill in the blanks about police violence against Black women as a necessary step in changing the reality of police violence against Black women. In order to do so, the campaign centers survivors.

Excerpted from #SayHerName: Black Women’s Stories of Police Violence and Public Silence by Kimberlé Crenshaw and the African American Policy Forum, with a foreword by Janelle Monáe. Copyright © 2023 by Kimberlé Crenshaw. Reprinted with permission from Haymarket Books.

Image: Robert Fairchild/Flickr/Inquest