The Jailhouse Lawyer

Calvin Duncan and Sophie Cull

Penguin Press, $32 (hardcover)

A deadline approached. Not for an individual man at the Louisiana State Penitentiary (better known as Angola); it was coming for all of them. From one end of the prison farm to the other, for every single one of the thousands of individuals incarcerated there. It was a deadline the legislature quietly adopted in 1990, and it applied to petitions for post-conviction relief across the state. Where there had been no deadline before, nearly everyone already incarcerated had to file an application by October 1, 1991, or otherwise be barred from review. A jailhouse lawyer named Calvin Duncan had discovered the law while doing some legal research early in 1991, a few months before the deadline was scheduled to take effect. Recognizing the deadline’s profound significance, Calvin alerted his fellow counsel substitutes (the official term for Louisiana’s authorized jailhouse lawyers) and together they worked behind the scenes to orchestrate an unprecedented effort at the prison:

The [prison] population was instructed to wait by their beds for a special broadcast from Warden Whitley. After calling for people’s attention and introducing his guests, Whitley handed the microphone to [attorney Keith] Nordyke [who] explained the new law, emphasizing the serious consequences of missing the filing deadline for both state and federal appeals. . . . The workers at the prison print shop had labored day and night to produce five thousand blank [post-conviction petition] applications for the inmate counsels to distribute throughout the prison. Applicants were assured that the inmate counsels would help them file the post-conviction petitions on time. . . . For the next four hours, the inmate counsels helped individuals across the prison complete their forms. Dorm partners stepped in to assist their illiterate peers, making sure every page was filled out.

Even for someone like me, a lawyer who has spent almost two decades working on Louisiana criminal cases, reading this description of events left me stunned. An entire prison—wardens, administrative staff, correctional officers, incarcerated workers in the legal programs department, and regular cell partners—worked together to protect the legal rights of thousands who had no access to counsel. The prison’s paper of record, the Angolite, observed: “The spirit of cooperation . . . was unheard of in the long history of Angola. . . . Nothing like it had ever happened before.”

In the prologue of his remarkable memoir The Jailhouse Lawyer, Calvin writes, “We as a society don’t get to hear stories of Black men helping each other.” In a book packed with these very stories, the example of how the men imprisoned at Angola helped each other avoid missing the deadline imposed by Louisiana Code of Criminal Procedure article 930.8 is one that stands out for its magnitude and depth. Understanding what they were up against, one cannot help but share in the ultimate hope Calvin harbors for his book: “I want the world to know that a group of Black men, in the darkest place in America—the incarceration capital of the world—rose above our situation to help each other.”

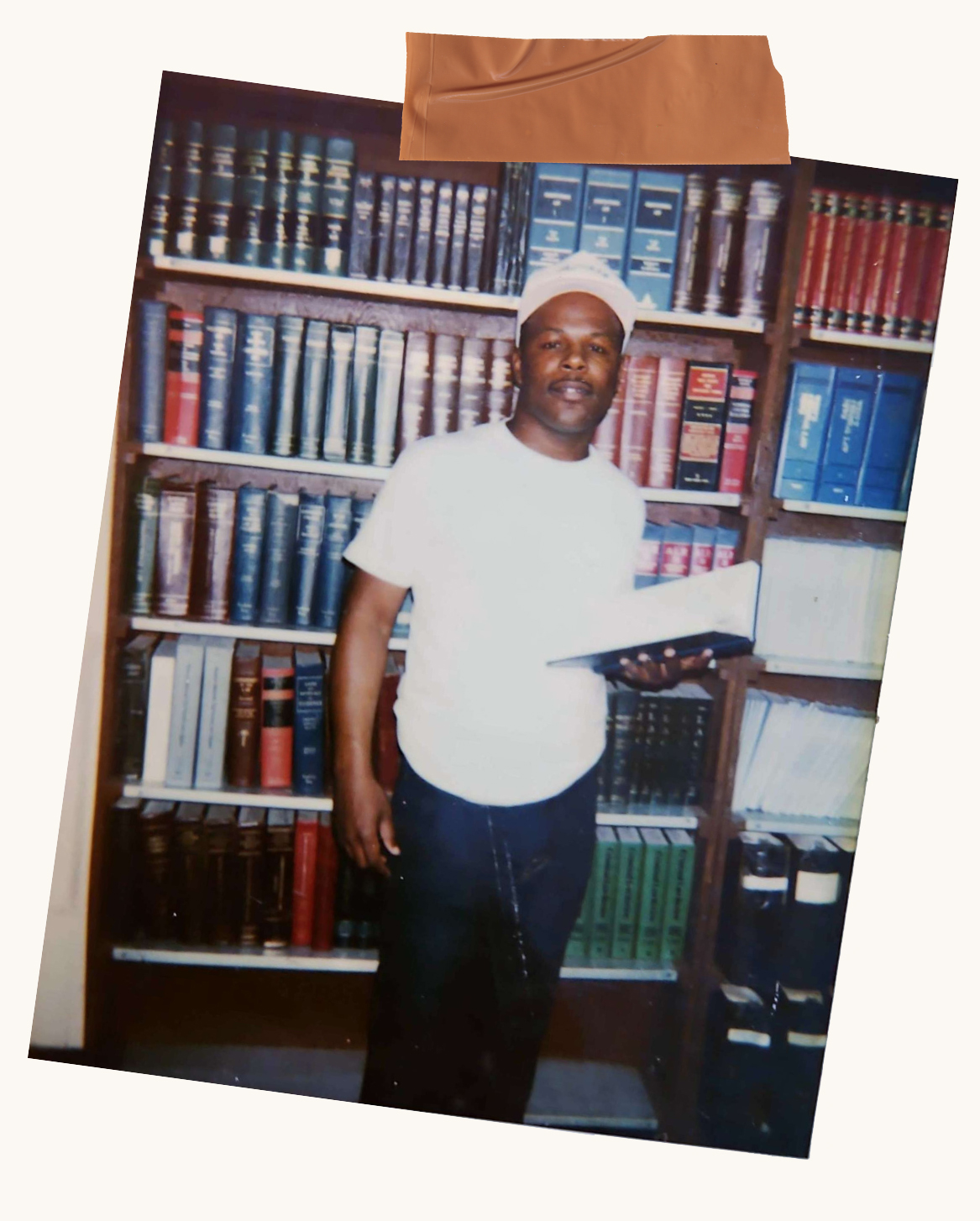

Arrested at the age of nineteen for a murder he did not commit, Calvin faced impossible odds in a criminal system designed to disempower. The Jailhouse Lawyer, which Calvin wrote with coauthor Sophie Cull (to whom I am married), describes the astounding journey by which he taught himself the law, worked diligently on the cases of hundreds of other men with whom he was incarcerated, and—after seeing so many go home before him—finally prevailed in his own case. It was a journey that lasted nearly three decades and, but for Calvin receiving help from the Innocence Project New Orleans, may still not have ended.

Since he was finally released from prison in 2011, Calvin has continued the work: cofounding a reentry organization; working as a paralegal on high-stakes criminal cases; cocreating a project that filmed interviews with more than a hundred men serving life-without-parole sentences; bringing the Supreme Court’s attention to Louisiana’s racist and unconstitutional nonunanimous jury verdict policy; completing both his undergraduate and law degrees; and assisting other jailhouse lawyers in their efforts to do their best work in very difficult circumstances.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Inquest, finalist for the 2025 National Magazine Award for General Excellence, brings you insights from the people working to create a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest in your inbox every Saturday.

Newsletter

Given who he is and how he is, Calvin’s story will be for many a much-needed balm in this time of agitation and dislocation. In it, readers may hear echoes of Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning or Primo Levi’s If This Is a Man—indelible stories about how some individuals subjected to incomprehensible degradation manage to find themselves and, in the process, develop the will to survive the worst. It should be no surprise then that the book is sometimes a difficult read; it was unquestionably even worse to live.

Calvin suffered indignities and legal setbacks that would make any fair-minded person want to break or throw things, or maybe even give up the fight altogether. For example, his lawyer—appointed to represent him in a capital trial at which his life was on the line—came to see him in the jail just one time. It was the night before the trial, and the attorney visited only to make sure Calvin had a suit to wear to court the next day. Decades later, on the precipice of his freedom, the judge presiding over his post-conviction petition would decide abruptly to adjourn a hearing before resolving the case—because he was going on vacation. As a result, Calvin was forced to spend one more Christmas locked up, his release postponed yet another month.

Calvin is not the only one in the story who suffered terribly at the hands of the criminal legal system. Consider Weasel, beaten to a pulp by a notorious captain and his goons, then forcibly medicated with Haldol until he began to lose his mind. And there was Calvin’s dear childhood friend Alvin Abbott, whose appellate lawyers effectively abandoned him, not once but twice. The journey The Jailhouse Lawyer takes readers on is packed with injustices of all stripes. As the book details poignantly, it didn’t matter to Calvin whether the men he assisted were innocent. What mattered was simply whether they needed and wanted help. If they did, Calvin was at the ready, with little regard for what doing right by others might cost him.

Fortunately, the book also offers many high notes of when Calvin and his protégés find success. We get to see Calvin learn how the law works as a tool, a weapon he could use in defense of his rights and the rights of others. From winning his very first motion—requesting that the court provide him with a law book—while inside the New Orleans jail to managing cases at Angola that eventually won relief from the Supreme Court, he fought and often won. And he did it as a man with a ninth-grade education, stuck in confinement, serving a life sentence.

Today I work with Calvin in the Jesuit Social Research Institute at Loyola University New Orleans. We share an office and work together on the Light of Justice program, which Calvin launched to keep supporting the state’s jailhouse lawyers and incarcerated people who have no right to counsel. This means not only that I am one of the luckiest lawyers in the country, but also that we get to discuss what the book could accomplish. The starting point for that discussion is our shared understanding that the criminal legal system which produced Calvin’s wrongful conviction in the 1980s is not a relic of the past.

Calvin’s experience as a jailhouse lawyer was inextricably intertwined with the legal and political developments that produced and accelerated mass incarceration. The book quietly distills a tragic but overlooked truth that has characterized the U.S. criminal system for more than three decades now: procedural hurdles erected by our governments transformed the courts into gymnasiums for legal acrobatics rather than halls of justice for resolving fundamental questions of fairness. In this world, it is an incarcerated person’s ability to meet statutory deadlines and navigate doctrines such as “exhaustion” and “default” that dictates whether they have any chance at enjoying their constitutional rights. During his transformation into a formidable legal advocate, Calvin anticipated that process would come to matter far more to the courts than substance, even for people who possess convincing evidence that they are innocent. In the procedural morass, many individuals have been lost, though some were lucky enough to find a guide like Calvin to steer them through.

When I reflect on the story of how the entire Angola prison population came together in 1991 to meet the new deadline imposed by article 930.8, I do not see a bygone era. Instead, I see the present day, folding itself back into the past. From 2017 to 2024, Louisiana enjoyed a brief but significant period of meaningful progress in reducing one of the highest incarceration rates on Earth. But the state government is again using process to subvert substance. At a special session in 2024, the state legislature hurriedly passed a raft of bills that—in addition to undoing critical decarceral reforms—made certain procedural barriers mandatory in all circumstances. Such a drastic change to the post-conviction landscape has devastating results for people in prison. For example, even if a judge, prosecutor, and defense attorney all agree that there are good reasons to spare a petition that was filed late, the new law provides no leeway: the petition must be thrown out.

The legislature did not stop there. A few months ago, it adopted a bill that rewrites the state’s post-conviction code, including article 930.8. Much as the federal Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 fundamentally changed the system of federal habeas review for all incarcerated people—even though the law was supposedly meant to target people sentenced to death—HB 675 does the same for Louisiana’s post-conviction process. Ostensibly drawn up to push death penalty cases through the system faster, the law creates new and damaging procedural obstacles for everyone to navigate. Those with sentences other than death have no right to a lawyer in post-conviction. Unless they can cobble together the funds to hire someone to represent them, they must rely upon themselves and the jailhouse lawyers.

With Louisiana positioned to continue its ruthless reign as the nation’s mass incarceration capital, The Jailhouse Lawyer arrives at a time and in a place it is needed more than ever. Beyond the compelling narrative and personality which shape Calvin’s extraordinary life story, the book crystallizes valuable lessons that people who care about mass incarceration need to learn. We are making the same sorts of legal and policy mistakes that took us down the dark path of permanent incarceration, with no consideration for the costs or consequences. In the face of this desperate reality, we are left to wonder: Will those in the prisons find a way to make miracles happen, the way Calvin did decades ago? And, critically, what will we on the outside do, especially knowing what we know now? For a time such as this, we need stories and we need spirit, and Calvin has generously supplied us with both.

Image: Calvin Duncan in the Angola Prison law library. Courtesy of Calvin Duncan.