On August 24, 2019, Elijah McClain stopped by a gas station in his hometown of Aurora, Colorado, to buy iced tea for himself and his cousin. As he waited in line holding the cans of tea, he adjusted his face-covering runner’s mask and, as he left the store, he gave his customary “gratitude bow” to the cashier before leaving.

Shortly after he left the 7–11 and began walking home, listening to music with his earbuds, a caller named Juan reported Elijah to 911:

He’s walking south on Billings Street; he has a mask on . . . when I passed by him, he put his hands up. He does all these kinds of . . . I don’t know. He looks sketchy. He might be a good person or a bad person. He has a full-on mask on.

Although nothing about this call suggested that anything approximating crime, violence, or danger was occurring, the 911 operator told the caller she would “put a call in so officers can go see what’s going on.” Officers came to the scene and stopped Elijah a block from home.

“Stop. Stop. I have a right to stop you ’cause you’re being suspicious!”

Aurora police officer Nathan Woodyard rushed toward twenty-three-year-old Elijah, one hand balled into a fist with index finger and thumb extended, pointing at Elijah as if to mimic a gun.

Elijah—“Eli,” to some—was confused. He stopped the music he was listening to and began pulling his headphones out of his ears to better hear and understand what was happening. But before he could process the interruption to his evening walk from the gas station, two other officers, Jason Rosenblatt and Randy Roedema, had joined the scene. The first officer began to grip and stroke Elijah’s torso, back, and waist.

Early in the encounter, Elijah entreated officers to stop touching him so forcefully. He told them that as an “introvert” he was uncomfortable with all of this unexpected touching and pleaded with officers to “please respect the boundaries that I am speaking.” Yet the swarm persisted. One officer commanded Elijah to “stop tensing up” and “relax.” Of course, demanding that a person stop being tense and stressed is not an effective way of discouraging those feelings. When Elijah insisted that he was merely “going home” to a place that was one block away, Woodyard responded in a threatening tone: “Relax—or I am going to have to change this situation.” The three officers pushed Elijah onto the ground and began applying “control techniques,” including a now-banned hold in which officers deliberately apply pressure to the carotid artery to cut off blood flow to the brain and induce unconsciousness.

After a struggle, throughout which Elijah was vomiting into his mask, struggling to breathe, and apologizing for upsetting the officers, the officers called in paramedics to subdue this 140-pound man. Paramedics arrived, hastily diagnosing an inconsistently conscious Elijah with “excited delirium”—a condition that many experts do not consider a legitimate medical diagnosis but rather one developed solely to justify the use of chemical restraints during police stops. The so-called rescuers injected Elijah with an overdose of a sedative, ketamine. Less than ten minutes later, Elijah’s heart stopped. After several days in a coma, his family removed his swollen and bruised body from life support.

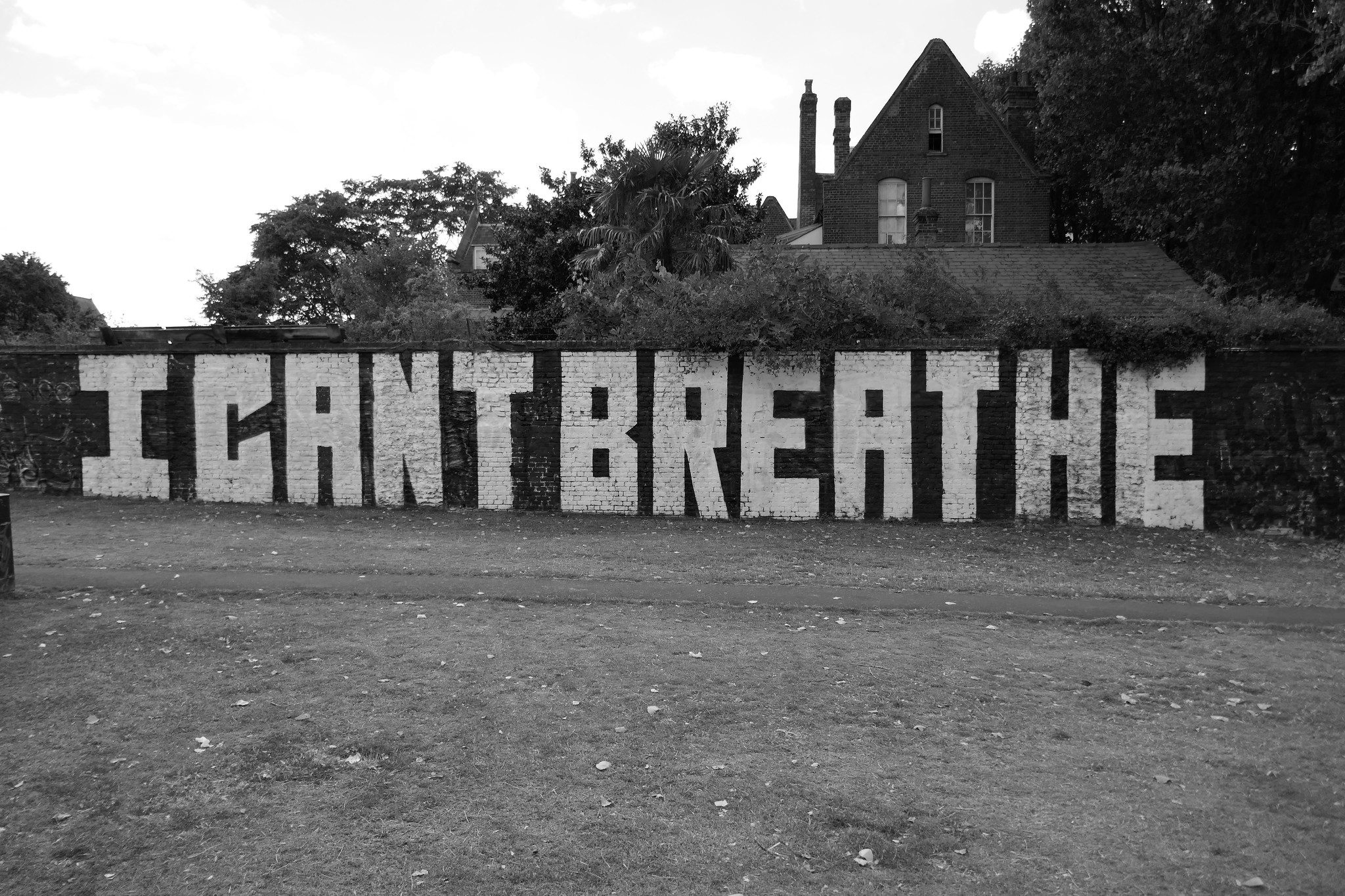

Since Elijah’s death, many have rightly focused outrage and activism against the officers and paramedics who killed him. His death underscores the interlocking problems of police authoritarianism, violence, and state failure to execute its duty of care for Black life.

Yet few have asked why the police and paramedics were interacting with Elijah at all. Why did the 911 dispatcher so quickly send police to stop Elijah when the caller did not report any dangerous behavior? Why call 911 in the first place? Although these moments of discretion seem more difficult to regulate than police and paramedic discretion may be, in them lies a key— but often ignored—set of components of “police reform.”

Implicit in the caller’s decision to call 911, and the 911 dispatcher’s choice to send officers merely “to see what was going on” were two assumptions. First was that unusual behavior on its own, regardless of whether it seems remotely connected to dangerousness, warrants response and investigation from armed agents of the state. Second was that, if in doubt about the dangerousness of a situation, a person should err on the side of bringing police in rather than leaving them out.

To make lasting change in our responses to crime and violence, these assumptions must fall.

By many accounts, including his own, Elijah was an unusual person. One of his former coworkers at Massage Envy, the spa where he was employed, described him as a “one-of-a-kind eccentric” who “naturally marched to his own drum.” Another coworker called him an “earthly angel” who was “inspired by everything.” One of his long-term massage clients took note of his “child-like spirit,” appreciating that he “lived in his own little world. He was never into, like, fitting in. He just was who he was.” As he pleaded with officers as they choked him, “I’m just different, that’s all.” The police and paramedics killed Elijah and they are responsible for doing so. Yet the chain of events that led to his death started simply because Juan—the person who called 911—thought Elijah was strange.

“Sketchiness” and “suspiciousness” are curious characterizations, seeming to arise from a correlated set of unspoken circumstances. Although the caller made much of Elijah’s runner’s mask, wearing a runner’s mask on its own cannot be considered “suspicious”—certainly not given that Elijah was a long-distance runner, and these masks protect runners’ faces from wind and cold weather. Elijah was not running at the time, but we hardly classify people as suspicious simply because they wear the incorrect attire for an occasion. In addition to the fact that Elijah was often cold, some of Elijah’s friends think he liked wearing the mask to cope with his sometimes crippling social anxiety.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

Juan said Elijah put his hands up as he passed, which the 911 dispatcher described to officers as “waving his arms.” But of course, handwaving is not an obvious prelude to criminal behavior either. There is some irony that the very position officers often demand from citizens they search, especially Black men—to raise their hands, to “assume the position”—was held out as a reason for suspicion. Elijah’s friends surmised that the handwaving and gesticulation was probably his dancing. Of course, Elijah might have been viewed as “sketchy” for other unspoken reasons—his race, his neighborhood, his gender, all the reasons that are rarely acknowledged explicitly these days, but that have long fed into Americans’ ideas about crime and danger.

Although demands for conformity in the United States are certainly intense, in some settings we view nonconformity as a characteristic worthy of protection or even celebration. For example, journalist Olga Khazan wrote an entire book glorifying human eccentricity, Weird: The Power of Being an Outsider in an Insider World. In Weird, Khazan argues that being unusual, not seeming to fit in with the mainstream, confers advantages in creativity and resilience.

Beyond such psychological considerations, U.S. constitutional principles—such as privacy and free expression—underscore the purported value of nonconformity at a collective level. In recent years, the appreciation of unusual perspectives and unusual behavior has been invoked not only to protect historically excluded viewpoints but as a key element of “anti–cancel culture” rhetoric. When more than 150 prominent scholars and writers signed a controversial letter, published in Harper’s Magazine in 2020, they emphasized how much they “need a culture that leaves us room for experimentation, risk taking, and even mistakes.” In 2022 the Massachusetts Institute for Technology issued a new proposed statement in support of free expression, touting its “tradition of celebrating provocative thinking, controversial views, and nonconformity” and proclaiming that such expression “is essential to the search for truth and justice.”

Obviously, the particular forms of nonconformity that these elite speakers are defending are not of the same type as Elijah’s quirky clothing choices and dancing in the street. One might argue that unusual expression directly intended to communicate an idea is more democratically or educationally salient than the type of self-expression Elijah exhibited that August night.

However, it is hard to shake the sense that had Elijah been a professor who lost his job for his unusual or even abhorrent views, rather than a massage therapist who lost his freedom and ultimately his life for unusual but non-criminal behavior, outrage at the state discipline against him would have been far greater in the first place. As much as the United States embraces free expression and nonconformity in principle, it has rejected those values as applied to Black men, among whom the slightest deviation from norms can provoke fear, policing, and punishment. Although Elijah’s masking and dancing were not a purposeful communication of ideas, they were in themselves repudiations of the narrow range of presentations Black men are allowed, part of a larger way of being that bucked expectations of Black masculinity and stoicism. As Black opinion editor Stephen A. Crockett, Jr., explained, “sensitive Black boys are not a rare breed—they exist in droves—but the world does its best to beat it out of them.”

Even those who are horrified by the police and paramedic killing of Elijah might be slower to criticize the 911 caller for reporting unusual behavior. Juan was not sure what was occurring and made a choice to err in favor of calling in police, hoping that even if he had summoned authorities when there was no danger, they would look for themselves and behave responsibly. Remember, even in the initial call, Juan was openly ambivalent about whether any danger was present. “He might be a good person or a bad person,” he told the dispatcher.

One reason for discomfort with criticizing the caller is that, especially in the two decades since 9/11, the United States has embraced mutual surveillance. As the slogan goes, “If you see something, say something.” A 2016Washington Post op-ed by Hanson O’Haver called the catchphrase “the unofficial slogan of post-9/11 America.” A New York advertising executive developed the phrase on September 12, 2001, and eventually it became a campaign of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. As O’Haver mused, “The expression makes us vigilant, but it also makes us paranoid.”

Good citizenship now requires watching other people closely to take note of “something” and report it to authorities. This mentality originated with concerns over international terrorism but is now so culturally embedded that it has knock-on effects for domestic policing as well. Yet the forms of “something” that warrant a report are rarely well defined. Thus 911 calls become a pathway along which the mundane activities of Black people are evidence of suspiciousness.

One change necessary for shrinking the role of policing in harm to Black people is complicating “see something, say something” culture. This culture encourages people to call authorities but exercises little discernment about whether public safety is truly at risk. Thus it misidentifies paranoid surveillance as good citizenship.

However, 911 calls are only one example of the ways that private suspicion, based on shallow notions of normalcy, has been weaponized for punishment. Longstanding programs such as Neighborhood Watch and newer social-media-driven approaches such as NextDoor are among the various techniques private individuals use in attempting to build safety in their communities. These tools present unaccounted-for risks to anyone who seems unusual or out of place. Indeed, aware of this risk, NextDoor now provides information about antiracism on its website, and it warns new members that one of four primary rules is not to engage in “racism, hateful language, or discrimination of any kind.” Yet, even as it offers resources on dynamics like implicit bias and racial privilege, it does not—perhaps cannot—directly confront prevalent private bias. The rise of private policing, too, presents a challenge for those who aim to change policing, whether from a reform-focused or abolitionist perspective.

In their conclusion to Excessive Punishment (in which a version of this article also appears), Bruce Western and Jeremy Travis note, “Punishment not only describes what criminal justice institutions do, but also signifies a relationship between the state and its citizens.” Yet punishment also describes a bundle of private relationships, those between human beings like Elijah and others like Juan. The story of Elijah heartbreakingly illustrates how punitiveness is the very fabric of how we respond not only to crime, but also to Blackness—especially to young Black men like Elijah, trying to live free in a world that refuses to allow it.

When members of the public see every deviation from the norm as a threat, and policing as the only reasonable response to threat, policing flourishes even outside the direct confines of the state. Transforming policing and ending mass incarceration require structural and policy change, but they also demand that we eradicate the carcerality in our hearts.

Excerpted from Excessive Punishment, edited by Lauren-Brooke Eisen. Copyright (c) 2024 Lauren-Brook Eisen. Used by arrangement with the Publisher, Columbia University Press. All rights reserved.

Image: Duncan Cumming/Flickr