Since 2018, court-ordered, pretrial electronic monitoring (EM) in San Francisco County has increased dramatically. Before 2018, the county rarely, if ever, released more than 100 people on pretrial EM each year. But by 2020, it was releasing more than 1,000 people on EM annually. The primary driver behind this striking and abrupt change was the In re Humphrey, a 2018 appellate court ruling that made two important changes to California’s bail procedures: First, that judges consider a defendant’s financial ability to pay before determining bail amounts; and second, that judges consider the least restrictive conditions necessary to ensure defendants would attend court hearings and not threaten public safety.

The appellate court’s message was clear: Individuals’ freedom should not be determined solely by their ability to post bail, and that if less restrictive alternative measures might be taken to secure the government’s interest in public safety and the court proceedings’ integrity, individuals should not lose their liberty.

Although pretrial EM had existed in San Francisco well before Humphrey, after the 2018 ruling, the county ramped up its use of this surveillance tool by over 300 percent, in the hopes of addressing concerns that community-based defendants would threaten public safety or miss scheduled court hearings. In a context where judges could no longer detain someone for being too poor to bail out of jail, judges began to rely much more heavily on pretrial EM, even though this was not necessarily the least restrictive option available to them. Program participants have been disproportionately male (88 percent), without stable housing (roughly 20 percent), and under 35 years of age. Pretrial EM participants are also disproportionately Black (43 percent) in a city with a very small (just 4 to 5 percent) and rapidly declining Black population.

By the time that the California Supreme Court affirmed the appellate court’s ruling in March of 2021, noteworthy changes were already evident in San Francisco County’s pretrial detention and release practices. Among filed cases, the likelihood of detention declined by three percentage points (from 25 percent to 22 percent), the percentage released on cash bail also declined by eight percentage points (from 22 to 14 percent), and the percentage who were released to assertive case management and electronic monitoring, the very alternatives suggested by the appellate court, increased by 14 percentage points (from 14 to 28 percent). In other words, the post-Humphrey landscape had a net-widening effect in that incarceration and e-carceration combined have kept more people under state control.

The growing reliance on pretrial EM has been met with opposition in San Francisco and beyond. Two arguments typically emerge from critics. First, they note that even among the most rigorously conducted studies, findings of pretrial EM’s relative efficacy are nonexistent, weak, and/or inconsistent. Second, centering the voices of system-involved people, they assert that pretrial EM is less an alternative to pretrial incarceration than a form of incarceration; EM is e-carceration, with many of jail’s attendant harms. In other words, where public safety and attendance at court hearings are concerned, not only is pretrial EM superfluous, but it also inflicts unjustified harm to defendants, their families, and the communities in which they live. For these reasons, critics argue that pretrial EM should not be a part of efforts to decarcerate. Less harm would result if people were released pretrial without EM.

Our current study is an effort to inform debates related to the second issue — the potential harms done to those court-ordered to participate in pretrial electronic monitoring. We ask the following questions: To what extent do program participants experience difficulties attempting to meet program obligations, and what is the nature of the difficulties they face? To what extent and how do the difficulties participants face put them at risk for noncompliance and future criminal legal system involvement? And how do threats of noncompliance interact with other major issues that system-involved people face to affect program outcomes?

To address these questions, we conducted in-depth, semi-structured interviews with a convenience sample of 66 people court-ordered between 2018 and 2020 to participate in pretrial EM in San Francisco County. We find that a higher percentage of people who struggled with housing insecurity and co-occurring disorders reported difficulty meeting program obligations, struggles that amplified their risks of noncompliance. Pretrial EM obligations also created struggles with housing, work, and social isolation, making successful program completion even more difficult and new contact with law enforcement more likely. We end with a discussion about the implications our findings have not only for debates about pretrial EM’s net-widening effects, but also for concerns about the criminal legal system’s stickiness.

How Pretrial EM Creates and Exacerbates Major Life Challenges

Like any contact with the criminal legal system, pretrial EM significantly impacted the lives of respondents. In housing, mental health and well-being, employment, and social capital, study participants reported several changes to their lives during and after their time on the device. Though some changes were positive — particularly those related to addiction and substance use — most changes were categorically negative.

Destabilized Housing

Finding and keeping safe, affordable, and stable housing became even more difficult under EM. Seven respondents reported that EM significantly narrowed their housing options in a housing market already characterized by chronic shortage. It did so in at least three ways. First, EM conditions often included orders to stay away from their homes. These stay-away orders were almost always the result of domestic disputes, but such conditions, understandable as they might have been, made some homeless and deprived them of the personal items they needed for survival. One respondent described how his stay-away order left him on the street with no access to vital resources:

When I got arrested, I told the police officer I need my wallet. “Can you guys get that for me?” They didn’t get my wallet. And then when I was released, I needed my work laptop, and I had no way to access that. I needed to go to work so my ass wouldn’t get fired. And so, when I was released, I was kind of left to my own devices — no wallet, no laptop — and I had to get those back. And so, I made communications that were not legal in order to get those items back before I could schedule a police escort to get my things. [I couldn’t even] even like feed myself. I didn’t have access to credit cards, ID, anything. It was left at the residence where I was ordered to stay away from.

In this situation, pretrial EM contributed to the respondent’s housing insecurity by including a stay-away order as a condition of release without providing alternative housing and much-needed access to the respondent’s belongings. Three respondents attributed their housing difficulties to this issue.

Second, pretrial EM contributed to housing insecurity by making housing difficult not only to search for but also to secure. It did so in two ways. For people on home detention, EM not only constrained where they could search but also the amount of time they could devote to searching. For instance, finding housing in the private market was near impossible. As one respondent explained:

I couldn’t just go look for an apartment. I had to wait until my errands time to be able to do that. It wasn’t until they put me on curfew. I had to try to take the opportunity to see apartments on Zillow. And I had to schedule them for my errand time, and that was difficult because a lot of people didn’t have those times [for Open Houses].

Furthermore, if home detainees wanted to visit open houses, meet with potential landlords, or otherwise engage in apartment searches outside of designated errand hours, they had to seek approval from the courts beforehand. Approval, however, required documentation; home detainees had to provide the courts with paperwork necessary to prove that they had an appointment before the courts approved their requests. Not only did these procedures delay the process of securing housing, assuming housing seekers could, but too often, getting needed paperwork meant making potential landlords aware that they were being monitored by the criminal legal system. For most landlords, this knowledge alone would disqualify program participants from further consideration because landlords would discriminate against them.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

Third, in the face of such barriers, many housing seekers give up housing searches altogether or deploy resources that, in the end, might do more harm than good. Expecting to be denied access to Section 8 housing because of his record of arrest and EM status, one respondent explains,

I was supposed to have housing in 2018, but I was incarcerated. So, I missed my appointment. I think I kind of canceled myself out for that. After that, I never really tried to sign up for Section 8 or none of that kind of stuff.

Worse still, barriers related to EM participation also seemed to increase the likelihood that EM participants resolved their housing issues by taking advantage of potentially unsafe opportunities. Those who could not find their own housing often relied on family members and friends for a place to stay, but this reliance sometimes forced respondents to live in places or with people who might negatively influence their behavior. One respondent explained that the only people who would feel comfortable taking him in — and doing so without judgment — were those who were also “in the life.”

While being on the electronic monitoring it is very hard to find a place to live and to find a job. People think that it’s scary. You look like you are a dangerous person, that you’re going to harm people. So, you really turn to a certain type of friend that doesn’t bat an eye at it. And nine out of ten times, those are not the greatest people. So, it’s a crapshoot after that, of bullshit. It’s difficult.

In these ways, conditions of pretrial EM release significantly constrained participants’ access to safe, affordable, and stable housing. , In doing so, they actually pushed participants toward seeking and accepting potentially unsafe circumstances.

Diminished Health and Well-Being

EM also appears to have worsened individuals’ mental and physical health and well-being. EM conditions were a source of depression, anxiety, isolation, stress, and other emotional and psychological states among almost three-quarters of study participants, or exacerbated conditions that already existed. Respondents reported that EM “made me a hermit,” “created anxiety of the unknown,” “made me less social,” “f-cked my self-esteem up,” and “[made] me depressed.” For 42 percent of respondents, devices also caused physical pain, bringing on cases ofswelling, rashes, and nerve damage in the ankle/foot area. This figure includes six people who experienced changes in weight. They either lost weight because of the stress and shame of having to wear the device outside, or they gained weight because of their inability or unwillingness to leave their homes to exercise.

Critics of EM have also reported that EM participation creates barriers to receiving healthcare. One barrier was court approval, which critics have reported is difficult to receive. Consistent with critics’ reports, one respondent in this study who requested the court’s approval to have an emergency dental procedure was denied because he had not provided proper documentation prior to the visit. He explained,

I was having a really bad toothache. I wanted to go in to see a dentist or get a tooth pulled, and [SFSO] told me ‘No.’ So, I have to pretty much stay home, in pain.

None of the other study participants raised this issue. However, this was because they anticipated major hurdles and did not attempt to access care. By opting out, they increased the likelihood of poorer health outcomes. A second barrier was stigma; a few participants expressed reluctance to leave home with a monitor on their ankle, ashamed about what the device would signal to others.

In rare instances, however, respondents reported that EM participation had positive impacts on their health and well-being. This was especially true for a few participants with addiction. Forced into sobriety while under surveillance, they believed the program gave them extra motivation to change their lives. As such, EM was an “opportunity to go out and prove myself and get off drugs,” although a nonsurveillance based, non-coercive approach of structured support might also have this result without attendant harms. For those who were forbidden from operating a vehicle, EM also forced them to exercise more — to walk to their appointments or to complete their errands. Still, important as these improvements were for the individuals who experienced them, they paled in comparison to the high costs to health and wellbeing that pretrial EM participants were otherwise made to pay.

Disrupted Labor Force Participation

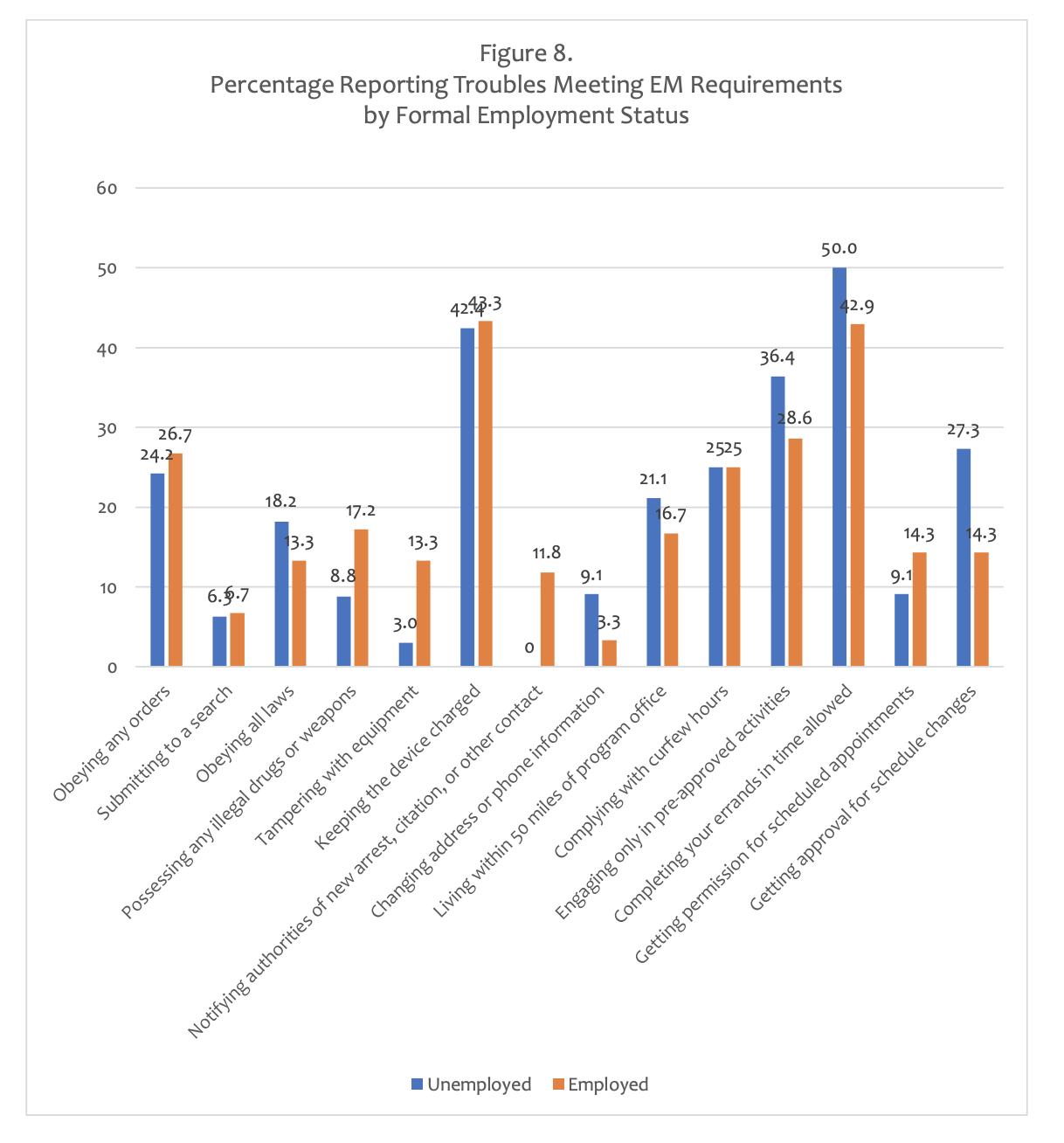

No matter their previous employment status, pretrial EM diminished individuals’ employment prospects. While our quantitative data suggests that similar percentages of employed and unemployed respondents were cited for noncompliance (see Figure 8), the qualitative data reveals variegated troubles for those with and without jobs in the pretrial EM program. This is primarily because several program requirements — residing within a 50-mile radius of the program office, abiding by curfew, keeping the device charged, engaging in only pre-approved activities, abiding by stay-away orders, and getting approval for schedule changes — made securing job offers and keeping jobs difficult. Even though it was a Sisyphean task to find and maintain a job while on EM, a few respondents noted that having a job could eventually relax the conditions of one’s e-carceration. As one respondent explained, “If you find a job, they let you go out. Any job.” For many, however, EM obligations were so all-encompassing that they avoided searching for work, were fired, or quit their jobs to avoid issues with SFSO.

One of the greatest challenges for both job-seeking and employed EM participants was scheduling, including getting court approval for schedule changes. This was an issue of particular relevance for those under assertive case management, a more intensive form of supervision. Those who wished to find work tried to fit in search activities during the time allotted for errands — two to four hours each week. If they were fortunate enough to be invited to interview, to visit work sites, or to attend other events that might put them in the pipeline for new jobs, they would need court approval to do so, since the timing of such events would likely not overlap with the severely limited times that program participants had available. Court approval required documentation — some form of evidence to support loosening restrictions — although such documentation was difficult to come by. While authorities could grant exceptions for restrictions to account for job interviews, respondents whose interviews were not officially “on the books” (as in, without a letter stating a date, time, and place), were not allowed to change their schedules to attend. One respondent explained the embarrassment of dealing with this obligation as follows:

I would get a random interview. [Employers] would call me, and if I would call [the program office] and let them know I have an interview tomorrow, they sometimes wouldn’t buy it, and then I’d have to reschedule. Stuff like that. Telling my employer … I mean, I never got that far, but what am I going to tell my employer, "I’m on house arrest? And could you please schedule ahead of time?"

Further, even when one authority found supporting documents sufficient to amend the schedule and allow the activity, another authority figure could override this determination. In one instance, the judge allowed for a schedule change, but the sheriff would not, resulting in a job-seeker being unable to attend their interview. This experience reveals both how much discretion layers of legal authorities have over the lives of pretrial EM participants and how capricious their decisions can be. For these reasons, seven study participants chose not to search for work at all while under supervision. As one respondent put it: “I didn’t even try to find [a job]. I wasn’t interested. It would have [been difficult] had I tried, though, because I couldn’t go anywhere.” Another respondent noted that “I didn’t want to have to tell my new employer that I needed to go to court, and I can’t show up to work,” so he opted out of looking for a job altogether.

Just as some job-seekers struggled to get approval to engage in job search activities because of difficulty securing approval for schedule changes, employed EM participants also often struggled to stay employed, forced to choose between difficult options. Those with “flexible schedules” and/or multiple employment sites faced huge challenges to get approval to go to work. For instance, employed EM participants had difficulty working within the 50-mile radius of the program office. This was particularly true for those employed in the gig economy, who juggled jobs with DoorDash, Uber, and other app-based work. For them, working inthe 50-mile radius and staying away from areas where they had stay-away-orders meant being very intentional about the trips they could take, including which income-generating opportunities they would have to decline. One respondent explained, “DoorDash and Postmates, and Caviar. It was all apps like that. So, I didn’t really have a boss. I just knew not to go over there, because the judge said not to. I would just stay away from there.”

But strictly abiding by EM program rules too often meant forsaking some of their employment commitments and risking their jobs — the primary source of income for many. Indeed, conditions of release often placed workers in the untenable position of having to choose between, on the one hand, making ends meet and potential reincarceration through technical violation or, on the other hand, remaining in compliance but being unable to care for themselves and their families financially. Many were willing to risk noncompliance — to break curfew, for instance, or to ignore stay-at-home orders — when these orders interfered with their ability to earn money. Indeed, a few reportedly broke curfew to work for companies, like DoorDash, whose peak hours often overlapped with curfew. As one respondent explained,

The times with DoorDash were that it could be a peak pay; it might be later in the night or something. And I have got to be in at 10:00. So, I don’t get to really do my whole overtime that I wanted to do for myself and get the more bang for the buck. It kind of like held me up from a couple of dollars.

Weighing the pros of surge pricing and higher payments against the cons of noncompliance, they often chose the former. When faced with EM-related challenges, however, others quit their jobs or were fired. In our sample, seven people reported losing their jobs because of difficulties with EM conditions; four quit and three were fired, but whether they quit or were fired, the end of their employment was rooted in the same underlying factor — EM inhibited their ability to be present and productive at work. Two respondents described how SFSO gave them faulty EM devices that would erroneously flag their places of employment as outside of the 50-mile radius. Each time, they had to visit the program office to rectify the situation. This was the case even though one respondent’s employer confirmed that he was at work.

Social Isolation

For a subset of respondents, pretrial EM had no discernible effect on their relationships with family members and friends. This was either because they had weak ties to family or friends (or very low levels of social capital) to begin with, as was the case for five respondents, or because they had very high levels of social capital, with very strong ties to family members and friends, as was the case for three respondents. Thus, the networks of one in eight pretrial EM participants seemed unaffected by program participation.

For those whose ties were neither very strong nor very weak, however, pretrial EM had a corrosive effect, weakening bonds of affection and instrumental aid, and pushing people toward social isolation. Growing isolation typically occurred in three ways. The first was through stigma and shame, which created distance between pretrial EM program participants, their family members and friends, and others in thelarger community. Pretrial EM program participants who felt ashamed by their status emotionally distanced themselves from family and close friends to avoid further embarrassment or feeling like a burden.

For some, the shame was so great that they avoided telling their close relations about their ankle monitor at all. EM program participation was particularly tricky for parents of young children. They often found it embarrassing and difficult to explain what the electronic monitor was, and why they had to wear it.

Many also documented that their families had secondhand stress as they worried about respondents, and others spoke about the stigma that came along with the monitor even though they had never been convicted of anything. Other causes of social isolation were geographic distance, time constraints, and stayaway orders that EM program participation placed on people.

Time and distance restrictions made parenting and caregiving especially difficult. In one particularly poignant example, one respondent’s girlfriend was in labor in another city. This respondent describes how he had to get approval to leave the city to be there for the birth of his child. He explains that he was approved to leave the city for two days to be with his girlfriend and newborn baby. Getting swept up in the hospital visits and time with his new baby, he ended up staying for three days, an immediate violation of his orders that resulted in a noncompliance report. While the noncompliance report was subsequently dismissed, this story is an extreme version of something that happened often: respondents lived too far away from their children to visit them regularly or participate in parenting the way they would have liked. In this way, EM may result in effects similar to parental incarceration, which is considered an Adverse Childhood Experience by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Many whose children lived within the 50-mile radius were prohibited from seeing their kids because of stay-away orders. This was the case for one respondent who reflected on the impact this arrangement had on the children as follows:

I think it bothered the younger ones because they didn’t have access to me. Weren’t able to be around them. I know my youngest son was very upset. He didn’t like it. He didn’t like the fact that I could only be around him for an hour a day. That bothered him a lot...He would just say that “I don’t like the fact that I can’t spend more time with you,” and “Why does it have to be like this?” “Why are these restrictions in place?” He didn’t like that at all. He was really upset with just the fact that he couldn’t have more time with me.

Others had stay away orders from their houses or wives, making it difficult to see their children even if they were not ordered to stay away from them explicitly.

Challenges to staying connected were more complicated for romantic partners and spouses. For some, EM restrictions were a nuisance that caused stress in their relationships because they could not go on dates, had to be wary of curfew hours, or had to stay within the 50-mile radius. Many who were not in relationships actively avoided them so as not to have to explain why they were being monitored pretrial. Others were on the monitor explicitly because of an issue with a significant other or spouse (ex. domestic violence situation with wife); these respondents described how EM prohibited them from seeing or talking to spouses/partners as an additional EM obligation. While this stipulation was meant to protect victims of domestic violence while their cases made their way through the criminal legal system, the solution was not always ideal; it caused extra stress for the parent who had primary custody of the children and responsibility for the household. Others suggested that stay-away orders unnecessarily limited contact and prevented them from working out their difficulties with their partner. This respondent had a mixture of all three of these issues.

Well, I didn’t talk to [my wife] during that time I was on it. After the whole case and everything was done, she was like, “Well, I wanted to talk to you, but I wasn’t able to. I wanted you to be able to come get the kids.” But the electronic monitoring prevented me from being within a certain radius of where she was at. So, she didn’t like it at all. She was very upset about it. She didn’t like the restrictions on it because she was like … it was hard for her to just do everything without any assistance from me. Basically, kind of taking me out of the equation, where I wasn’t able to really do anything. It was just said that I couldn’t have any contact with her or my kids. But it wasn’t really her that was doing it. She said it was more of the court system. The district attorney, they were the ones really pushing for it. And they weren’t really giving her a chance to speak. This is not something that she wanted at all.

The result: Not only was he unable to see his wife and children, but he was also unable to participate in and contribute to their lives. For some even with strong ties, the constraints that conditions of pretrial EM were too much. Indeed, it was among those with greater access to social capital that we see higher rates of noncompliance. Those who were noncompliant regarding notifying authorities of new arrests, citations, or other contact with the criminal legal system; complying with curfew hours; engaging only in pre-approved activities; and getting approval for schedule changes had greater access to social capital that could offer instrumental and/or emotional support when compared to those who were compliant on each of these measures. Much like some workers who chose to violate conditions that interfered with their ability to earn money through work, respondents with greater stores of social capital would act in ways that violated the conditions of their release — breaking curfew, engaging in activities that had not been pre-approved, or failing to get approval for schedule changes — to bridge the physical and emotional distance that separated them from family members and friends.

How Respondents Perceive EM Relative to Jail

Among study participants, attitudes about EM were mixed. While some described it as a “blessing,” others characterized it as “bullshit.” Several reflected on EM positively. For instance, one respondent described how EM “gave me time to chill,” to think about his addiction as well as how to better his life. Another respondent who contemplated acting violently toward her abuser but did not because she feared further legal troubles suggested that EM “probably kept me sane. No. Made me kind of feel like I was going insane. But I think in retrospect, literally probably kept me sane [laugh].” Most of those who characterized EM in positive terms, however, did so solely because it allowed them to escape harsh conditions of jail confinement.

For those who contrasted pretrial EM with a pretrial period free of penal supervision, however, EM was viewed quite negatively. They were confused about why EM was necessary when they presented a low risk of failure to appear in court and a low risk of harming anyone pretrial. They were upset that EM in effect led them to “waive my right to a speedy trial.” Indeed, perhaps especially as the pandemic raged, it became clear to several that their time on the ankle monitor would far outlast any possible time they would have had in jail. They were frustrated with the “frivolous technology” that seemed to have so much power over their lives. On EM, they felt demeaned by the fact that they had so little control over their own lives. As one respondent explained, I “feel like somebody else owns you. Somebody else is in control of your life. For the moment. Like a f-cking dog. Less than.”

Indeed, they felt enslaved. For too many, pretrial EM “simulated slavery with me.” The physicality of the ankle monitor, operating like a shackle with digital tracking, likely contributed to that conclusion.

Most respondents, however, held a mix of views. Even if pretrial EM was better than pretrial incarceration, they could not ignore the hardships that pretrial EM created and the harms that it caused them, directly and indirectly. One respondent described how EM “takes away your constitutional right to illegal searches and seizures,” but shortly after described that “electronic monitoring — as embarrassing and shameful as it would be — beats jail any day of the week ten times over. So, any kind of shame and drama, or hoops that one would have to jump through to deal with electronic monitoring is well worth it, compared to the alternative of incarceration.” Another respondent shared a similar view: “It’s a joy to be out of jail, and a blessing to be on [an] ankle monitor, I felt like. But it was a whole other frying pot to jump into. You’re not in jail, but there’s a new stress — and it’s, if not bigger than jail was … it made me feel like I was cattle. And that these life-changing decisions by people that I’ve never even seen, or talked to, or know me at all were going to be based off of things like my ankle monitor performance. It made me feel hopeless.” Another echoed the earlier sentiments: “You got something around your leg, and you’re being monitored. You’re like, ‘Damn, I ain’t got no freedom.’.… But I’m free. You know? You don’t have to worry about no jail… I had to accept it.” Given these reflections, “e-carceration” seems an apt term for pretrial EM.

Pretrial EM highlights how positive legal rulings like Humphrey can result in reformist reforms that extend the criminal legal system in ways that most acutely impact the system’s most marginalized. Reforms like pretrial EM, while presumably meant as a move toward decarceration, end up trapping participants in cycles of interaction with the criminal legal system even before they have been convicted of the crime(s) for which they are being monitored. As a result, EM, like incarceration itself, reproduces inequalities by race and class and prevents participants from becoming full members of society.

Pretrial electronic monitoring highlights how positive legal rulings like Humphrey can result in reformist reforms that extend the criminal legal system in ways that most acutely impact the system’s most marginalized.

What’s next? Given the serious issues that we and others before us have raised, reform-minded people might react by trying to address aspects of the pretrial EM system that do harm. We suggest another path — that San Francisco significantly and substantially scale back its use of pretrial EM and use it only for the very limited types of offenses for which there is strong empirical support of its efficacy relative to pretrial release without EM. In all other instances, pretrial EM should be denied in favor of pretrial release without EM. In a context where limited evidence from rigorous studies exists to support the efficacy of pretrial EM over release without EM, and with a growing body of evidence that pretrial EM does real and potentially long-lasting harm to those released, significantly and substantially scaling back is the only evidence-based approach that is consistent with treating pretrial EM as the most restrictive condition of release.

Further, given that many of the issues participants confront while on EM relate to the significant life challenges they face — most notably housing insecurity and co-occurring disorders — San Franciscans would be better served by investing in long-term, safe, and affordable housing as well as easily accessible, strong supports for those with both mental health and substance use disorder issues, the very people at greatest risk of frequent contact with the criminal legal system.

Excerpted from “Between a Rock and a Hard Place: The Social Costs of Pretrial Electronic Monitoring in San Francisco,” by Sandra Susan Smith and Cierra Robson, a Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Working Paper published in September 2022.

Image: Saketh Garuda/Unsplash