One’s debt to society should not be a poor person’s tax cloaked as a mandatory court surcharge. Being removed from society, for however long the court sentences someone to do time, is already a debt to society and should not be compounded by fees.

Inside a college program at the prison where I’m incarcerated in New York, I met C.J., 24, a deep thinker, debater, and funny chap. We affectionately called him “young Clark Kent” or “Peter Parker” (the Tobey Maguire version). I often ran into C.J. in commissary because we had the same store visiting days.

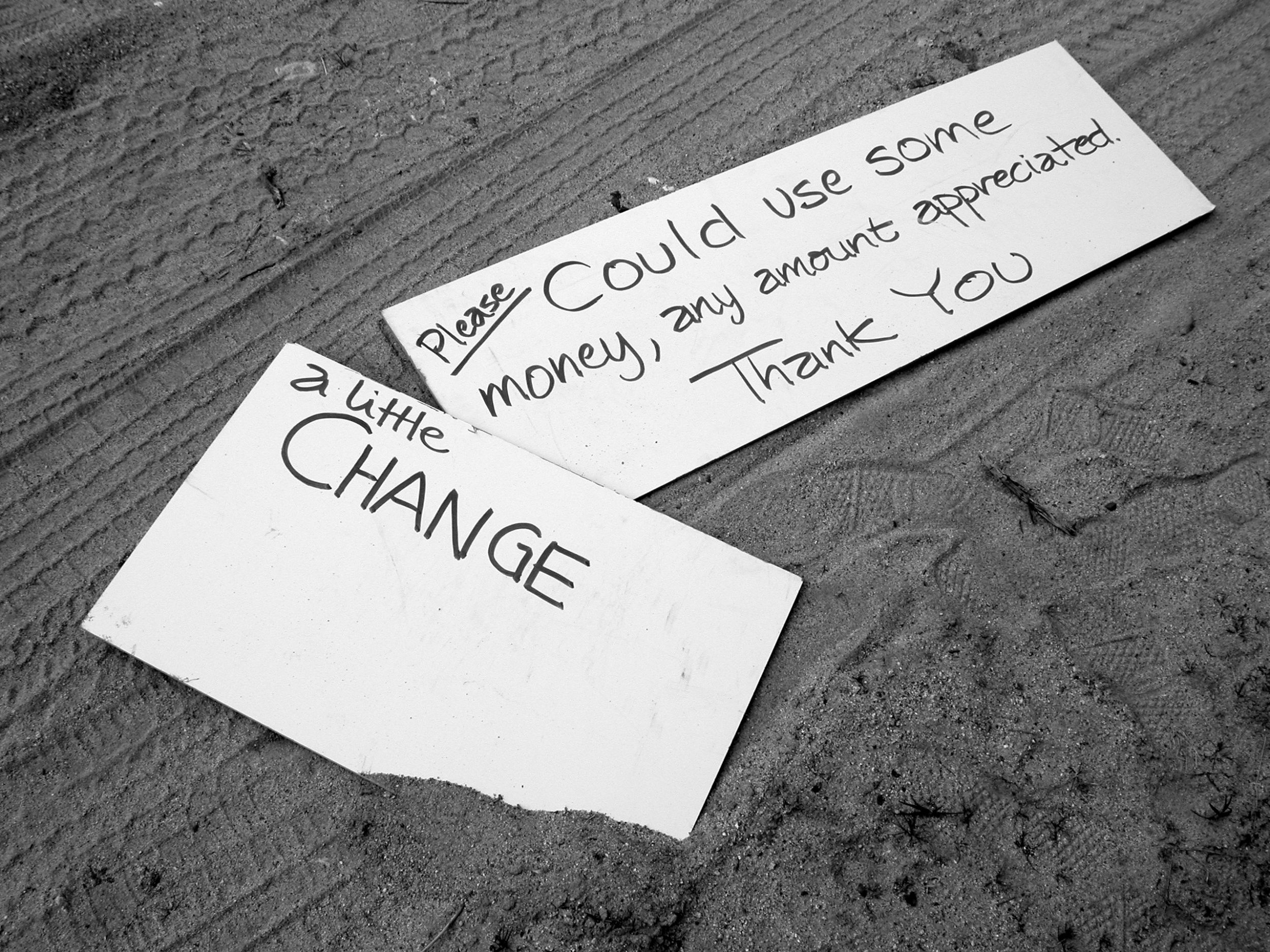

At commissary, C.J. purchased what he could, which was usually a Degree deodorant (or some toiletry item) and a Nutty Buddy ice cream cone—always a Nutty Buddy ice cream cone, as if holding on to a memory from his life before prison. It’s all he could afford with his program pay. Over the course of two years, we gradually became friends, and I eventually felt comfortable inquiring about his support network. He told me that he does have one, but because his mandatory court fees and restitution fees are in the six figures, the money that his mom sends him is hardly enough to get by after his court fees and restitution charges are taken out.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

After learning this, each visiting day I would pretend I had bought the wrong brand of coffee, or a snack I couldn’t possible eat—too many calories for me!—and I would offer it to C.J. For a few months before he was moved and I sadly stopped being able to see him, C.J. indulged my suggestion that he’d be doing me a favor if he’d accept my “incorrect” purchases—so as not to force me to discard them into the wastebasket.

I always wanted to pick up something extra for him when I shopped for myself. I believe that he deserves it. He never asks for anything; he would literally give someone the shirt off his own back; and if not for his exorbitant mandatory court fees and restitution charges, he could make do with the funds his mom sends him.

Many people don’t know about the obscure, greedy New York Penal Law § 60.35, which prevents C.J. and others from getting by. It creates a host of mandatory charges imposed by the court on people convicted of various crimes.

For example, people convicted in New York of a felony are charged $300 per conviction. A DNA swab is taken from every incarcerated person and the banking of the DNA profile costs $50 for each “new” conviction, even if a new test is not required. These compound: a special report on mandatory surcharges from the New York City Bar explains, “if a defendant is convicted of two felony offenses for different criminal acts, and is sentenced on the same day, he is required to pay $750 in mandatory fees and surcharges.”

The same law also mandates that incarcerated people pay into victim restitution funds and, if applicable, pay for their own sex offense registration. Different categories of crimes have different fees. Also, not all fees are mandated, or the court is given a wide range for the amount that can be imposed. Ultimately, what this means is that it’s impossible for someone to predict what they’ll be expected in total to pay. Additionally, while incarcerated, any person committed to New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision (NYDOCCS) can be subjugated to an arbitrary $5 fee for disciplinary infractions, restitution of damaged or lost property, or cell damage if found guilty by correctional staff. These charges are under the NYDOCCS Directive 2788, entitled “Collection & Repayment of Inmate Advances & Obligations.”

Court fees become routine burdens, officially called “encumbrances,” for incarcerated individuals and their families. According to Directive 2788, “when a new encumbrance is established, all spendable funds will be applied to the collection.” This means that if sufficient funds are available in an inmate’s account to pay off an encumbrance, the amount available will be immediately garnished. In the event that the balance due is unsatisfied, encumbrances will be collected at 20 percent from the incarcerated individual’s prison pay, which ranges from $0.10 to $0.65 an hour, with the majority making $0.25 an hour—rates that haven’t been adjusted since the early 1980s. Encumbrances are also collected at 25 percent from outside receipts, which includes money sent by incarcerated people’s families, friends, or significant others.

Not everyone is losing sleep over incarcerated individuals being exploited through prison labor, but I think everyone can agree, as a matter of labor justice, that a full day’s work should afford one the ability to purchase healthy food and adequate hygiene items. To supplement their highly processed prison diets, incarcerated people either purchase fruits and vegetables from the commissary’s sparse (and often sold out) selection, or they have these food items bought at an approved vendor and sent to them by loved ones. Incarcerated individuals must also purchase their own hygiene products, since NYDOCCS provides only a single roll of toilet paper and two bars of Corcraft soap doled out weekly or biweekly, depending on the prison’s inventory.

Keep in mind, as prison laborers, incarcerated individuals are sometimes the producers of the very soap that they are subsequently given. Prisoners either program (work in a particular industry) and earn $6 to $8 every two weeks, or work in the prison’s industry (think plantation/factory) and earn a few more dollars in addition to the $6 to $8 every two weeks.

What prisoners earn is far from enough for them to survive without financial assistance from their outside prison support system. This love-burden falls on incarcerated individuals’ families, friends, and significant others and not infrequently leaves them impoverished, too. A few facts: the Prison Policy Initiative reports that of the approximately 2 million currently incarcerated people in the United States, 37 percent of those people are Black. According to a 2020 Census Bureau report, the average Black median household income between 2015 and 2019 was $43,935 (compared to $68,785 for non-Hispanic white households). In 2021 the U.S. Census Bureau reported that between 2019 and 2020, 19.5 percent of non-Hispanic Black people (in comparison with 8.2 percent of non-Hispanic white people) were living at poverty level. Furthermore, in November 2023, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that the 2022 unemployment rate for Black Americans was 6.1 percent, compared to 3.2 percent for non-Hispanic white Americans.

All this to say, incarcerated people’s outside supporters are often barely making it themselves. So pulling out one’s Mastercard, checkbook (if those still exist), or cash to help pay mandatory surcharges for one’s incarcerated child, friend, or loved one is harder than some readers might imagine.

Among New York state’s incarcerated population, many people owe exploitative court fees that are holding their entire families captive to debt. For example, Aladdin, an incarcerated person at Eastern New York Correctional Facility, told me: “I am court ordered to pay nearly $42,000, but the court knows I will never make that kind of money while incarcerated. My financial albatross falls squarely on my wife Keilyn’s shoulders. We sacrifice as a family, to pay what we can.”

Aladdin’s parting words haunted me for days: “How does forcing my family to pay ‘my’ surcharges keep New Yorkers safer? It doesn’t.”

I agree. Mandatory surcharges normalize, even make banal, the charging of exorbitantly high fees as taxes levied against law breakers. Those in power know full well that not many people are going to stick their necks out to right this horrific law, and incarcerated people and their families are left to deal with the consequences.

This essay was produced and published in partnership with Empowerment Avenue.

Image: Unsplash