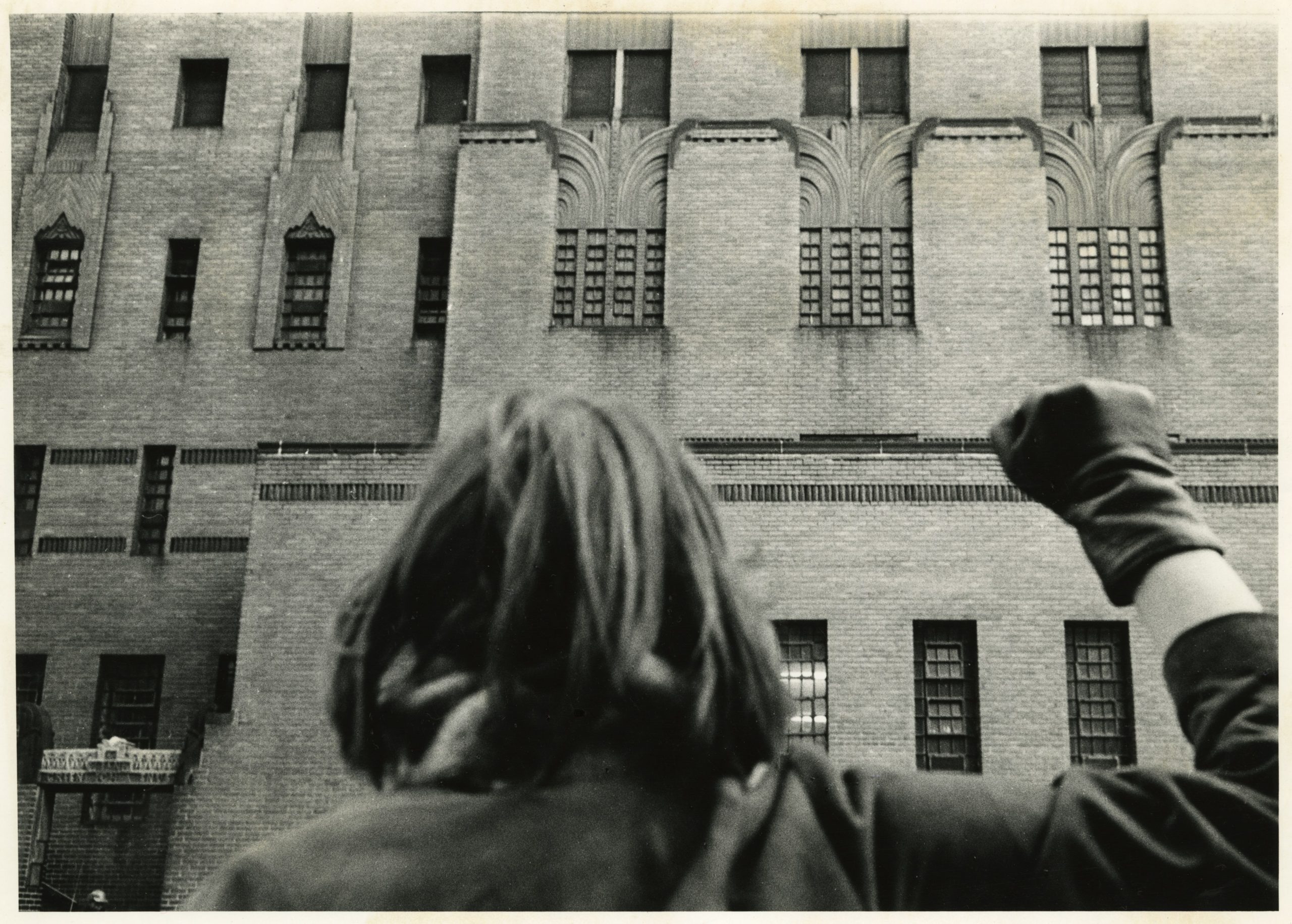

Today it’s hard to imagine a prison in Greenwich Village, one of New York City’s most picturesque (and unaffordable) neighborhoods. But for almost as long as there has been a Greenwich Village—which is to say, almost as long as there has been a United States—detention centers have been an integral part of village life. The last of them, the Women’s House of Detention, stood from 1929 to 1974. It was one of the village’s most famous landmarks. And for tens of thousands of arrested women and transmasculine people from every corner of the city, the House of D was a nexus.

Jay Toole, for example, first ended up in the orbit of the House of D when she was thirteen, in 1960. Some friends had given her the haircut every cool boy wanted: a tight-fade flattop, just like Steve McQueen. That was the final straw for her father—a violent, sexually abusive man who ruled their Bronx home with his fists. That night, he threw her out, and Jay lived among the queer kids on the streets of the village for the next twenty-five years. At the age when most of her peers started high school, Jay started heroin. In 1964 she stole a taxi to drive her girlfriend to California, but they only made it as far as Texas before they were caught, and Jay was sentenced to her first bid in the House of D.

For Jay the prison was complicated: dangerous, vile, violent, dirty, cruel—but also a place where she met other queer people, and one of the centers of her queer community. Today, Jay is an advocate for formerly incarcerated queer people, and she leads tours telling young people about the queer history of the House of D. And make no mistake: the House of D was a queer landmark. In truth, all prisons are, especially ones intended for women.

Today approximately 40 percent of people incarcerated in women’s detention facilities are part of the broad LBTQ spectrum (compared to about 3.5 percent of the general population). We live in the age of mass incarceration. If we extrapolate these findings to the nearly 250,000 women currently incarcerated in the United States, at least 100,000 are queer. During the years the House of D was active, which spanned the single most homophobic period in U.S. history, the percentage of queer people it caged was almost certainly higher. Records show that queer women and transmasculine people were sentenced to the House of D for such crimes as smoking, forgery, petit larceny, being homeless, attempting suicide, murder, wearing pants, sending the definition of the word lesbian through the mail, “associating with idle or vicious persons,” staying out late, accepting a ride from a man, vagrancy, alcoholism, prostitution, possession of narcotics, “waywardism,” disobedience, stealing rare books, being alone on the street, rape, drug addiction, and lesbianism itself. Yet the impacts of queer people on prison history, and the impacts of prisons on queer history, are rarely examined. Even when they are, the focus is mostly on men.

When I began sketching out the idea for The Women’s House of Detention: A Queer History of a Forgotten Prison, I had a naive understanding that prisons were bad. I might even have described them as “broken.” But to look at prisons historically is to see a monstrously efficient system, doing exactly what it was designed to do: hide every social problem we refuse to deal with.

Prisons have very little to do with “justice” or “rehabilitation.” If they did, we would be up in arms about the fact that 200,000 people are sexually assaulted while incarcerated every single year—and that’s not even counting those who are violated by the routine procedures of “health care” in prisons and jails, or those who never report being assaulted out of fear or shame or simple recognition that the system does not care.

If one in twelve people sentenced to prison were also sentenced to be raped for their “crimes,” we would call that barbaric. But when one in twelve people is sexually violated as collateral damage to their imprisonment, we call that justice.

As abolitionist Mariame Kaba writes in We Do This ’Til We Free Us (2021), calls for prison reform “ignore the reality that an institution grounded in the commodification of human beings, through torture and the deprivation of their liberty, cannot be made good. . . . Cages confine people, not the conditions that facilitated their harms or the mentalities that perpetuate violence.”

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

Researching The Women’s House of Detention, I began to see the connections between abolition and my hopes for the queer movement writ large. Abolition moves us away from a paradigm of “legal” versus “illegal,” and toward one of “harm” versus—what?

To me, the opposite of harm is care—the thing we owe one another, the thing we cannot live without, the thing the government should take a vested (and financial) interest in promoting. Yet we starve our systems of care while we feed the beast of incarceration. Our social safety net, from health care to the shelter system to welfare, is badly frayed, and our government has confused promoting a specific family type (heterosexual and nuclear) with promoting interpersonal care generally.

On Friday, September 24, 1954, as the last glints of sun snuck below the low horizon of the village’s row houses, a howling began to reverberate through the streets. In the House of D, dozens—perhaps hundreds—of women were screaming. “We want to get out! The food is no good! They’ve killed a girl in here!”

The women pounded their institutional metal cups against the cell bars, giving their screams a sharp and tinny backbeat. If the large crowd that gathered looked closely, they would have seen the flickering light of a fire raging somewhere on the fourth floor. But getting too close to the prison was a dicey proposition, as those on the inside began hurling ceramic dishes and lit cigarettes at the crowd. It took hours for the guards to regain control.

There would be several more riots in 1958, as well as ones in ’69, ’70, and ’71, right before the prison closed for good. These later riots were all connected to larger movements, either held in sympathy with queer, Black, or feminist protestors gathered outside the building or inspired by the wave of prison protests that rocked the country in the early 1970s. As prison historians have noted, “Rioting was, and remains, one of the few ways for prisoners to ensure that they would not be ignored.” In part for this reason, most prisons are now built far away from people who might act as witnesses to what happens on the inside. The riots in the House of D in the 1950s shook the prison to its core, exposed its many flaws to the public, generated several internal and external investigations, caused the entire prison administration to be upended, and started the (long, frequently delayed) process of tearing the place down.

“Cherokee” was one of the girls in the prison in the summer of 1954 and into that fateful September. A wayward minor of seventeen, she’d grown up in New York City, though her father was from Georgia and her mother from Fajardo, Puerto Rico. She’d been institutionalized for two years on a charge of “delinquency” but had only the slimmest of files—she had a tendency to disappear quickly. The prison officials noted her “psychosexual confusion” and desire to wear slacks, her “destructive influence over others,” how “something electric seems to happen when she walks in the room,” and how “girls vie with one another to be near her.” The matrons considered her an invitation to trouble.

Around the time Cherokee was incarcerated, city officials labeled the entire Department of Correction “extremely understaffed and almost completely demoralized.” The House of D in particular was hemorrhaging personnel. At the time of the riot, they were about thirty guards short of being fully staffed, and 60 percent of the entire staff had been newly hired as of 1952.

While the guards were few, the imprisoned women were many. That September, the city’s correctional system hit an all-time population high. There were some 452 people imprisoned at the House of D the week of the riot, which meant that at least a hundred of them were doubled up in cells that were only seven feet long by six feet wide, or stuffed into temporary dorms made from converted dining rooms. The housing floors were tense and overcrowded. Sutter’s Bakery, a fancy French pastry shop, had recently opened across the street—a sign of the village’s escalating gentrification—and many women in the prison recalled the smell of baking pastries as a painful daily reminder of the world they were kept from.

While in the House of D, Cherokee kept herself busy by writing personal notes to her girlfriends—women on the outside or at one of the other institutions she’d been at before, like the Hudson Training School for Girls or Bedford Hills. Shortly before the riot, a matron discovered her love letters and destroyed them, sending Cherokee into a fury. It was one thing for the prison to censor outgoing letters, or notes passed between imprisoned women, but these were private notes for herself, which (theoretically) Cherokee should have been allowed to write undisturbed. As punishment, she would have been sent to the fourth-floor isolation cells, where addicts and, increasingly, queer people were sent—the same floor where the riot soon began.

Conditions on the fourth floor were some of the worst in the House of D. Imprisoned women in general were treated poorly, but those who had drug addictions were treated worst of all. According to investigations done after the riot, about 35 percent of those imprisoned at the House of D that year were drug users. They were forced to wear institutional blue chambray dresses so everyone would know and thrown together in their misery to kick on the fourth floor without any real assistance. Is it any wonder they were always among the first to resist?

After the 1954 riot, the House of D discontinued the fourth-floor junkie tank and began sending addicts in withdrawal to the tenth-floor hospital—at best a marginal improvement. A new deputy warden, meanwhile, endorsed the same prescription for fixing the prison that had now been repeated for years: the overcrowding needed to be eased; a new building needed to be built; and most of the “crimes” for which women were arrested should never be handled in the criminal legal system.

Commissioner Anna Kross trumpeted the report throughout her administration (and even seemed to leak parts of it to the press) in an effort to bring real, substantive changes to the House of D. In 1956, following her lead, Mayor Robert Wagner officially endorsed a plan to relocate the House of D to North Brother Island—a craggy, cursed spit of land near Rikers Island (the men’s prison) that had previously served as a smallpox sanitarium. For the next decade, the government would wrangle over plans and costs, and while some improvements would be made to the House of D, the idea of the soon-to-come new building was frequently used to deny budgetary requests and other improvements at the existing prison. In the end, it was all for nothing: North Brother Island would become a drug treatment center, and the House of D would remain in the village until 1971.

In the wake of the 1954 riot, Commissioner Kross was able to make some changes. Two social service workers were added to the staff of the House of D, as were nearly thirty guards. Every prison in the city was equipped with a Diagnostic Unit, which provided (limited) psychiatric treatment and counseling—and, finally, these services were put in the official budget, not funded with money spent by inmates in the commissary. Three vocational programs were established in the House of D, one for waitresses, one for seamstresses, and one for hairdressers, though each served fewer than thirty people a year, out of thousands. A Medical Advisory Board was launched to offer outside consultation and oversight for prison health services, and Quaker volunteers were brought in to provide entertainment and discussion groups. Heating was added to the roof, to allow for some limited outdoor recreation time during the winter, and televisions were added to the indoor recreation spaces (greatly increasing the noise in the building). Finally, in 1957, the policy of giving women a mere dime upon release was abolished. For the rest of the prison’s existence, women sentenced for misdemeanors would receive a whole quarter on their way out the door! Felons could get as much as five dollars.

Not all the changes made were positive, however. In 1956 the Department of Corrections finally codified in writing the process for segregating queer women and transmasculine people:

Should there be any information on the accompanying card or commitment that might indicate sex deviation by an inmate or should the receiving room officer have knowledge through past experience that the inmate is known to be homosexual, then the receiving room officer makes the assignment to a single cell in a proper location and informs the floor officer by telephone concerning the characteristic of the inmate.

Technically, this policy remained in effect at least until 1964, when a researcher reported that queer women in the prison were not only segregated, they were forced to wear a “D” on their clothing, for deviant. However, her report also makes clear that the vast majority of people in the prison lived queer lives (at least while in the House of D), and that this form of public humiliation was used both arbitrarily and as a way of punishing people who were too masculine or too difficult. Toole, whose story opened this essay, laughed when asked if queer people were segregated during her time in the prison in the ’60s, saying it just wasn’t possible: “There were too many of us.”

Excerpted from The Women’s House of Detention: A Queer History of a Forgotten Prison by Hugh Ryan. Copyright © 2022. Available from Bold Type Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

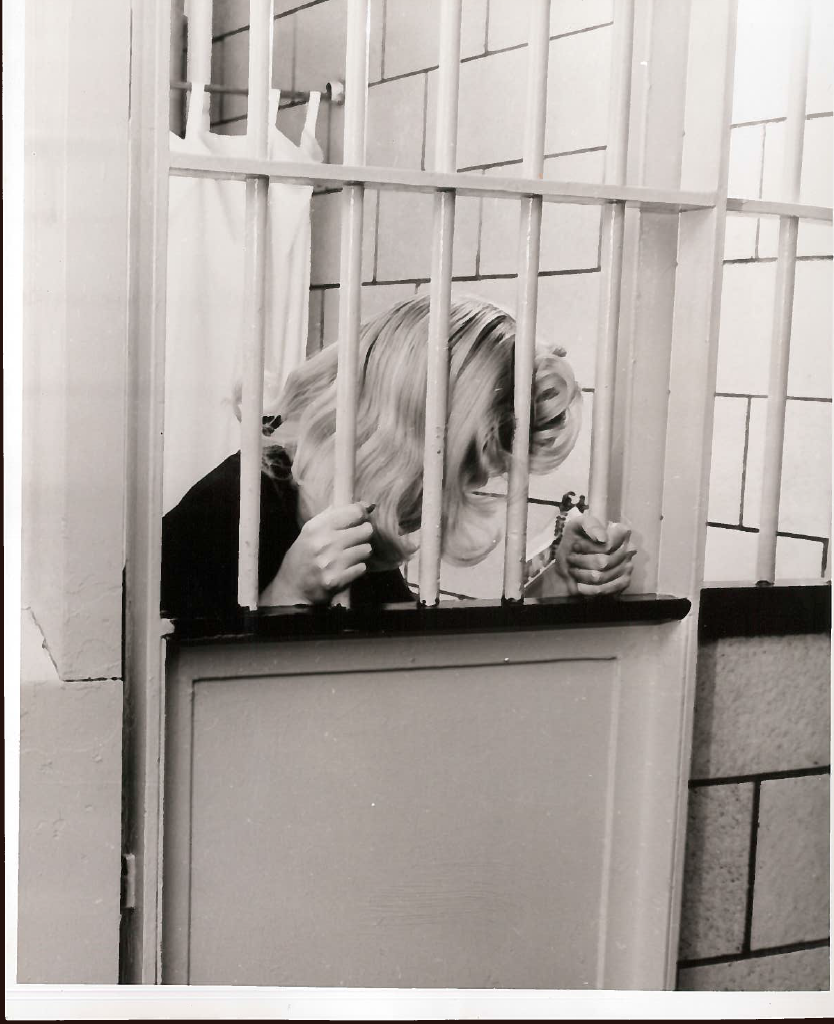

Header image: New York City Department of Correction publicity still from 1956.