I have often had conversations with other people who have life experience as sex workers or involvement in the sex trade and street economy in which we discuss our bodies as the actual physical site, the actual geographical location, where the intersection of racism, misogyny, transphobia, capitalism, and violence plays out. Because of this, my journey to politicization from “fuck the police” to prison abolition as an adult was not about theory. It was about being a witness. A witness to the violence in my own life and the lives of people I loved and cared for.

After my experiences with the police, the connections between sexual violence and policing were made clear to me on a different level. The people incarcerated in the minimum-security prison where I worked had almost all been arrested for breaking the law for income-generating purposes. They were in the sex trade, stealing, or participating in some other form of the street economy, like hiding drugs in their bodies for dealers or providing some other nontaxable services. I began to understand that our survival was criminalized, and that the size and damage of the penalties depended on what we were doing, in what neighborhood, and what we looked like. As I made the connections between racism, capitalism, misogyny, transphobia, and criminalization, I began to understand that for those whose lives are criminalized, fighting off an individual officer’s sexual predation was only one small part of the picture of the prison industrial complex.

At the same time, I was volunteering for the local syringe exchange while some of my chronic pain and disabilities were getting diagnosed slowly and often incorrectly. My access to health care was shit. I had no real health insurance to speak of, and I was so busy lying to my doctors (and nearly everyone I knew) about my life that I started to see the connections between the medical model, prisons, the war on drugs, and the cops. Lying helped me to understand that hiding was an essential part of navigating systems, because to be transparent about my whole life meant denial of treatment and facing possible criminalization. If I told a doctor I was opioid dependent, I would not get the critical medications and care for my chronic illnesses and disabilities. The medical industrial complex and PIC were, and are, interlocking systems, benefiting from the exploitation of nearly everybody I have ever intimately interacted with.

I believe that survivors of sexual violence have a secret stash of power; we grow our insight out of a need for protection, out of needs to anticipate a violent swipe or someone grabbing us off the street. Some people also form this sixth sense out of generational understanding and awareness of how to escape white racist predators, and they hone psychic practices that allow us to apprehend danger. The survivors I met during this time formed underground networks of safe houses that ignored traditional social service models, including domestic violence shelters, because so few people got help from those places. From where I sat, drug users, people in the sex trade, transgender people, and LGBTI people were thrown out or refused help by shelters, hospitals, police stations, and even soup kitchens every single day — all the places we were socialized to believe would help and protect us only criminalized us further and trained us to lie to get our needs met.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

I began to see that all the shelters where I worked or stayed were not reducing problems but making them worse. I saw the shelters fight to expand carceral strategies, from mandated reporting laws to sentencing for people who purchase sex to the expansion of domestic violence courts. It was the mid-1990s, mass incarceration and drug arrests were rampant, and I could not wrap my head around how to be a feminist who did not believe in the state or institutions supported by the state. I was experiencing what Emi Koyama describes in her essay, “Disloyal to Feminism: Abuse of Survivors Within the Domestic Violence Shelter System.” Emi writes:

Feminist movements have struggled to confront abuse of power and control within our very movements, even as we critique and resist the abuse within this sexist society. On a theoretical level, at least, we now know that not all of our experiences are the same nor necessarily similar, that claiming universality of experiences inherently functions to privilege white, middle-class, and otherwise already privileged by making their participation in these systems of oppression invisible. We now know, for example, that fighting racism requires not only the obliteration of personal prejudices against people of different races, but also the active disloyalty to white supremacy and all of the structures that perpetuate systems of oppression and privilege.

Emi’s foundational essay shows the deep flaws in the ways that the state and the nonprofit-industrial complex address sexual violence and purport to support survivors. It is clear that a person’s identities are surveilled, policed, and punished in the person’s attempts, simply, to live. Emi’s own thoughts helped me to understand my struggles reconciling my feminist ideas and the stated feminist goals of the shelter. My feminism is rooted in transformative justice, harm reduction, and abolition; it is clearly anti-carceral, pro-BIPOC, pro-trans, pro-queer, pro-sex work/pro-ho, and anti-colonialist/pro-rematriation. The shelter’s ideas of feminism were based on perfect, passive, submissive victims needing help from the state; they subscribed to carceral feminism. In my own practice, and in key collaborations, I’ve attempted to take to heart many of the lessons and methods Emi lays out.

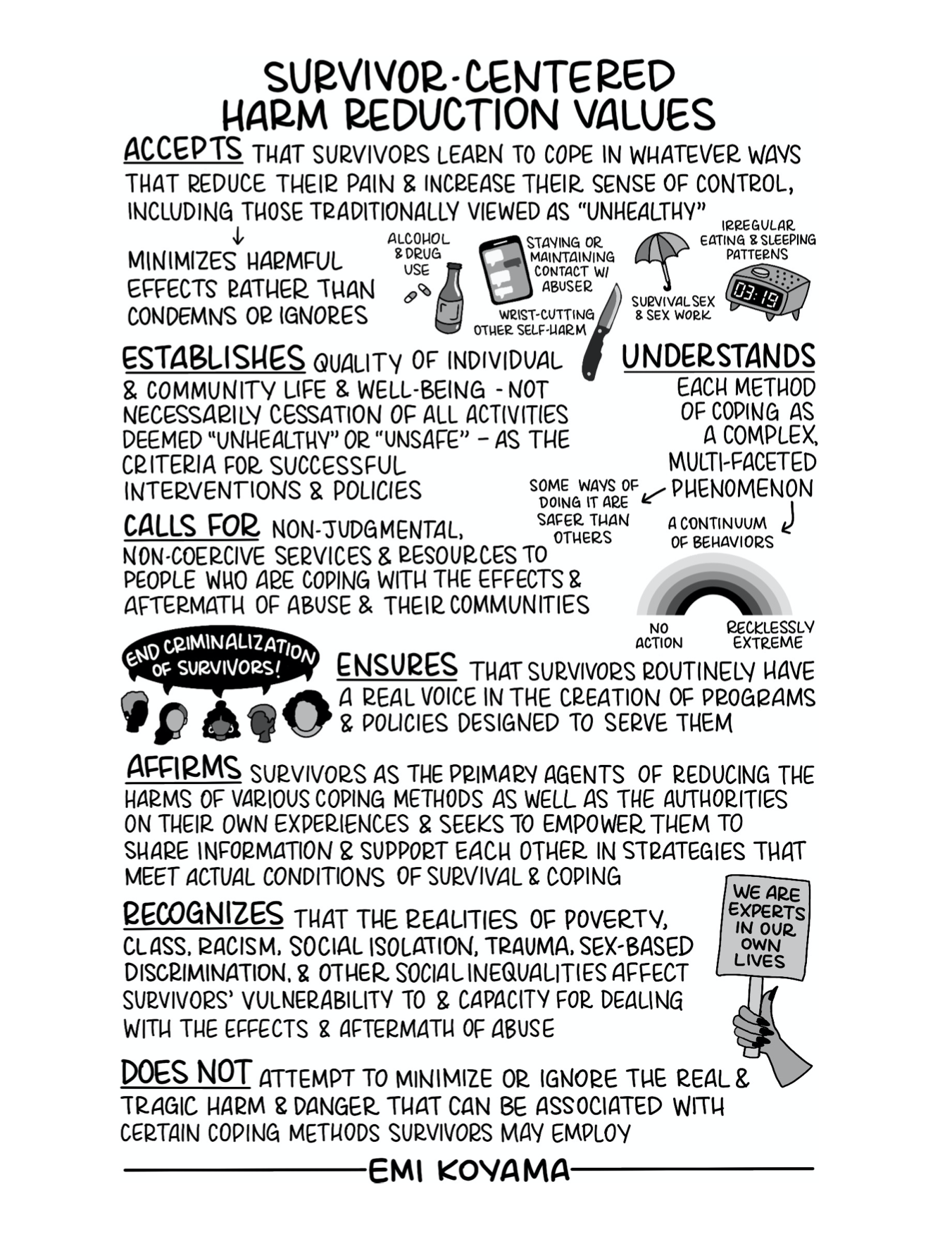

Emi Koyama’s zines were some of the first writings I found that linked the antiviolence work and violent world I was living in with harm reduction. The National Harm Reduction Coalition gave us the principles for U.S. harm-reduction practice (see the image above), which are still radical and rarely fully practiced in public health settings. Emi took the principles from NHRC and updated them to reflect the trauma-based work being done by those of us who identified as survivors. Focused primarily on intimate partner violence, domestic violence, and violence in the sex trade, in sex work, and in the street economy, the image we created for this book is taken word for word from her zine written in the late 1990s. When I reread what she wrote then, I am painfully aware of how relevant it is, how little has changed, and how necessary it is for us to have a clear understanding of the role of violence, trauma, and survivorship in our harm reduction practice.

Excerpted from Saving Our Own Lives: A Liberatory Practice of Harm Reduction. Copyright © 2022 by Shira Hassan. Reprinted with permission from Haymarket Books.

Image: Osman Rana/Unsplash