Contrary to assumptions that abolitionists don’t care about safety, we care a great deal about it. We recognize that safety is a basic human need. We think, talk, and strategize about it constantly in order to bring more of us closer to it. A commitment to creating genuine and lasting safety for all is what drives our desire to remake the world. Our organizing and advocacy toward a world free of policing is rooted in the reality that, for many of us, the cops offer no solution to violence, and in fact are the killers, rapists, home invaders and looters, destroyers of lives, families, and communities. They are what stands between us and the resources we need to ensure our collective safety and survival.

Ultimately, achieving greater safety requires us to divest financially, ideologically, and emotionally from the violence of policing. That means speaking to and confronting fears arising from the basic human need for safety and survival, which are fueled by propaganda and social policy that offer police and the carceral state as the only possible ways to meet those needs.

As abolitionists, we begin by asking open and generative questions that don’t limit our imaginations to policing: What does safety look like for you and for your communities? What conditions would increase safety for as many people as possible? We engage individuals and communities on their concrete concerns around what might happen if police no longer exist by asking questions like: Are you in danger right now? Are you worried about being robbed or assaulted? What have the police done in the past when you or people you love have faced this danger? What do you think the police would do if you faced this danger in the future? If the police were helpful, how were they helpful? If you imagine they would be, what, specifically do you envision them doing? Could that function be performed by someone who could be helpful without posing a danger to you and other people in your community? Who would be part of strengthening rather than destroying communities? Could this danger be prevented by ensuring your material needs are met or by transforming conditions and cultures of violence? Are you worried about what to do in case you are harmed in the future? What happens if someone commits a mass shooting? Are you worried about your own capacity to keep yourself and each other safe? Are you worried about retribution if you try to intervene to prevent harm?

For the majority of people and communities affected by violence, our sense of safety is often informed by the safety we didn’t get — from police, or anyone else — when we did face harm. We hold a wishful hope that next time, cops will get it right. For many communities, police are the only government resource available to meet any and all needs, conflicts, and harms. The notion of removing police raises fear of further abandonment to violence in the absence of any structures or institutions to ensure safety or meet community needs. We need to hold our communities’ fears with care while simultaneously building a shared understanding of violence and harm that includes the violence of police and fellow community members, of how we might go about creating genuine safety together, in ways that recognize the interconnectedness of our existence, without leaving anyone behind.

Abolition also requires us to unpack the notion of safety itself. While safety is a basic and universal human need, it doesn’t have a universal and singular definition. No individual or society can be “perfectly safe” at all times and under all conditions. All of us are vulnerable — to the elements, to natural threats like earthquakes or hurricanes, to harm caused by other inhabitants of this planet, to the uncertainty of human existence in a vast universe. Of course, we are not all equally at risk. Our vulnerability to natural disaster, violence, trauma — and our access to opportunities to heal from them — are structured by relations of racial capitalism.

The state’s carceral safety robs our communities of the conditions and nutrients that would allow true safety to grow, forcing us into the position of constantly reaching for more security from the very institutions that make us collectively less safe. Police fuel insecurity by constantly reminding us that we are never ever safe, with or without them. They then weaponize this insecurity to enact untold violence, always in the name of producing an impossible and elusive “safety.” Their presence represents and announces an absence of safety rather than an embodiment of it.

The state’s carceral safety robs our communities of the conditions and nutrients that would allow true safety to grow, forcing us into the position of constantly reaching for more security from the very institutions that make us collectively less safe.

Ultimately, we need to recognize and break with this obtunded conception of safety, the illusory carceral safety presented as something only the state can produce. To preserve this conception of safety, the state stokes our fear of one another, discouraging and interfering with our ability to care for each other. We see concrete evidence of this in the ways that police critique deescalation training, resist efforts to create nonpolice crisis response teams, and actively interfere with violence prevention and interruption initiatives. We’re not usually at our best when we’re afraid, and we are made even more afraid of each other through the politics of safety.

We also need to let go of the idea that safety is a state of being that can be personally or permanently achieved. Safety isn’t a commodity that can be manufactured and sold to us by the carceral state or private corporations. Nor is safety a static state of being. Safety is dependent on social relations and operates relative to conditions: We are more or less safe depending on our relationship to others and our access to the resources we need to survive. In her short film The Giverny Document, Ja’Tovia Gary asks Black women passing a subway station in Harlem whether they feel safe in their bodies, in their communities, in society. Their answers were equivocal and relative: It depends, they said, on conditions like who they are with, whether their health aide is nearby, where they are, what time of day it is, or if they believe God is with them.

If you ask anyone on any given day if they feel more or less safe, their answer will depend on a multitude of things. Did they just get paid and so feel less anxious about rent? Did they go outside or did they stay home all day? Did they log on to the internet and find themselves bombarded by copaganda and stories of violent crime, missing white women, and mass shootings? Do they have people to lean on if some calamity befalls them or will they be left alone to navigate and make sense of it? These conceptions of safety are more nuanced than absolute, more relational than categorical. The more functional and vital question we face is how to create more safety for more people while acknowledging that the concept of safety is contested and its meanings aren’t fixed.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

Abolitionists see safety as a set of resources, relationships, skills, and tools that can be developed, disseminated, and deployed to prevent, interrupt, and heal from harm. We want to increase the number of tools that increase safety for as many people as possible; get rid of the tools that don’t actually serve us, like policing and punishment; and undermine the fear driving the politics of safety. Building and strengthening the relationships we need to create collective safety requires us to overcome the fear of and alienation from each other that the state has perpetuated. Collective care is a form of reciprocal community support that Krystle Okafor describes as “how we make each other possible.” Ultimately, there will be no safety that we don’t make through collective care and the relationships it requires.

This view of safety presents a challenge, as carceral systems tell us that solutions to violence are simple, straightforward, and absolute. We have been conditioned to see safety in a form only the state can provide. Abolitionists are therefore often expected to offer alternatives based on what currently exists — to take a job away from the police and reassign it to someone else — often a member of the “soft police.” Responses to violence that don’t rely on police or policing appear to be more complex, exhausting, naïve or impossible. Or, they are simply illegible to us as “safety.” The current approach to “public safety” actually increases risk of premature death, yet we cling to the thing that is failing us. We have to do the work of rejecting the politics of safety, and the carceral and militarized visions of safety, that we have been conditioned to believe are the only path forward.

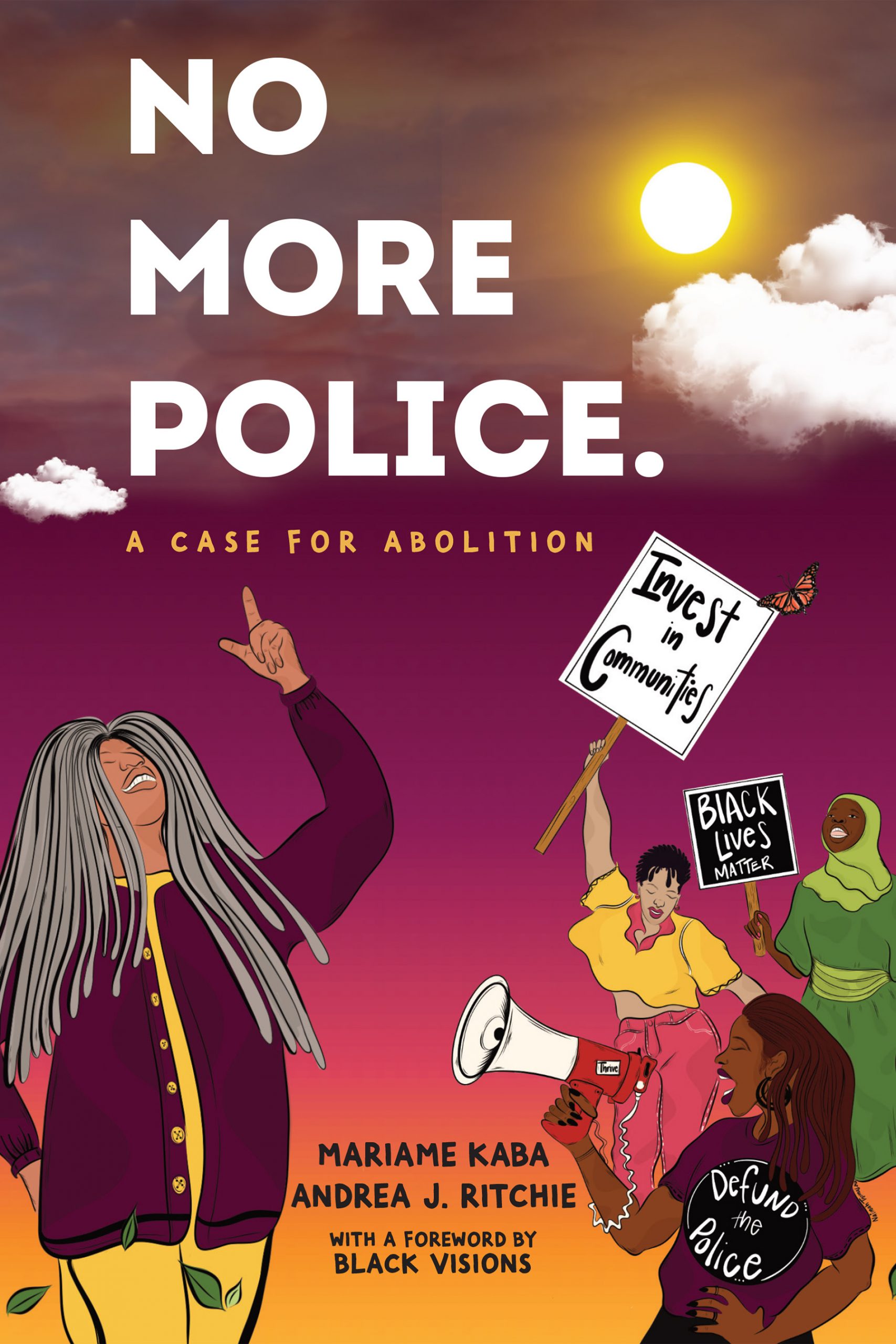

Copyright © 2022 by Mariame Kaba and Andrea J. Ritchie. This excerpt is adapted from No More Police: A Case for Abolition, published by The New Press. Available in simultaneous hardcover and trade paperback. Reprinted here with permission.