In the mid 1990s, medical neglect in California’s state prisons for women hit a crisis point. People at both the Central California Women’s Facility in Chowchilla and the California Institution for Women in Chino were dying in startling numbers due to inadequate health care. Treatable conditions were being mismanaged or ignored, collective mental health was suffering, and recourse seemed nonexistent. In this context, Charisse “Happy” Shumate, along with other life term prisoners, began mounting a campaign to stem this state-sponsored violence. Bringing together the energies of existing collectivities of which they were a part, such as Convicted Women Against Abuse, African American Women Prisoners Association, Mexican American Resource Association, Women’s Advisory Council, and the Long-Termers Organization, these activists documented examples of medical abuse and neglect, forged connections with activists and advocates in the “free world,” and turned to the courts for justice. Their class action lawsuit Shumate v. Wilson (1995) not only resulted in a mandate for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation to improve prison medical care, but also fueled further activism by inspiring numerous prisoners to become “proactive about their own healthcare.”

These actions — caring for each other in the face of prison violence, reaching out across prison walls, and pushing back against narratives of crime and punishment — would become the foundation for the California Coalition for Women Prisoners. Now, 25 years later, CCWP is a statewide organization that continues to challenge the myriad violences imposed on people in California’s women’s prisons. And the day-to-day ways in which members behind bars care for one another and help ensure each other’s survival continue to be the beacon, and the condition of possibility, for this coalition.

From its inception, CCWP has grounded its abolitionist politics in building relationships and collectivities within prisons and across prison walls, insisting that no one is disposable or forgettable. This feminist relational politics takes shape first and foremost through the community organizing and care work of incarcerated members. Helping each other survive the everyday violences of prison is, in and of itself, political resistance.

CCWP’s abolitionist feminist politics are perhaps best summed up by its motto, caring collectively. Caring collectively for people in women’s prisons over the last 25 years has meant refusing false and undermining dichotomies of “violent” and “nonviolent,” victim and perpetrator, survival work and political resistance; and fighting to improve prison conditions and to abolish imprisonment. It has meant fierce, persistent organizing inside of prisons, advocating for “non-reformist reforms” that improve conditions of confinement and forge pathways for release, relationship-building across walls and organizations, and “not mess[ing] over people in the name of politics,” in the words of the Combahee River Collective. And as CCWP touchstone and cofounder Shumate wrote in the first issue of The Fire Inside, “the battle must go on.”

REFLECTIONS ON THE CALIFORNIA COALITION FOR WOMEN PRISONERS

To mark the 25th anniversary of the founding of CCWP, we asked members on both sides of the walls to share their reflections, either in writing or through conversation, on the organization’s history, its contributions to the movement for abolition, and its practices of caring collectively. Below are excerpts from conversations with and written reflections by more than two dozen CCWP members, the majority of whom are currently or formerly incarcerated in California’s state prisons for women.

How did you first get involved with CCWP?

Mary Shields: Happy [Charisse Shumate] stood up for us and did something. Something like 24 people had died in two weeks from medical neglect [at the California Correctional Women’s Facility]. I worked in the infirmary, so I saw so many problems. Happy told me to remember everything, not to write anything down in case I got searched. So I remembered all the problems and told Happy later. She wrote it all down. She got everyone to do this, got us to remember the problems without writing them down, and then tell her. She organized all of us, got more and more of us to report the mistreatment. And she started getting really serious about reaching out to people outside. She kept going and going until she reached people who would help. She kept her notes in a legal folder so it couldn’t be searched, but she still wrote everything in code, just in case. Finally, she got in touch with a group of ladies who really wanted to know what was going on. That’s how legal visiting got started. And Happy pulled me right into it. CCWP then became a group around ‘94 or ‘95. I still have the first Fire Inside.

It’s not a me thing; it’s a we thing.

Charisse “Happy” Shumate Co-founder of Coalition for Women Prisoners

Anonymous: My first involvement was when I read a copy of the Fire Inside in 2010 at VSPW [Valley State Prison for Women]. That was my first year in prison, newly arrived from county jail. That newsletter gave me hope again when I was feeling hopeless, facing a 26 year sentence that had been mishandled by public defenders. Conviction was, for me, something worse than what I actually was guilty of. I felt a great deal of shame, low self-esteem, and traumatic pain. I found myself engulfed in deep grief, and surrounded by many other women, fellow peers, especially [the] long-termers and lifers and LWOPs who were also grieving in the same way. Every issue of the newsletter has helped me feel less isolated, and more hopeful and worthy to live on as I heal, change, grow, and transform.

CCWP turns 25 this year. What do you want people to know about the organization’s history?

Eva Nagao: CCWP is not just a coalition for women and trans prisoners, it is a coalition started and driven by women and trans prisoners.

Diana Block: We wanted to build an organization that took direction from the women/trans people inside and could also offer a place where former prisoners and women of color could develop their leadership. We wanted to fight the racism and gender violence that was central to the prison system and challenge the very existence of the prison industrial complex. We wanted CCWP to become a community as well as an organization. And we wanted to put visiting in the women’s prisons at the core of our organization. Over the past 25 years, we have consistently upheld these values and organizing methods.

Laura Purviance: The thing that most sticks out to me is the commuted — LWOPs who are now working with CCWP outside — these are outstanding human beings. They had been in contact with CCWP, and I can better appreciate now how that support helped them to show others in positions of authority that they deserved another chance. Those previously incarcerated people were group leaders, peer mentors, and community pillars who had far transcended the actions of their pasts which put them in prison. Seeing pictures and articles of them continuing the fight out there to help us who are still inside is so uplifting. That is the sort of legacy CCWP facilitates.

One of CCWP’s mottos is “Caring Collectively.” What does this mean to you, and what does it look like in CCWP’s work?

Romarilyn Ralston: I think Charisse Shumate, our founder, is the perfect example of “caring collectively.” It was her caring, collectively, that got us where we are today. You know, she wasn’t thinking about her own illness, and her own suffering. She thought a lot about other people around her. And she rallied the troops, and got people involved in being proactive about their own health care. You bring others in. And so it became an “inside-out” collective of people caring about each other. So I think we continue in that tradition. Even through some of the worst times of the prison regime here in California — the 1990s was one of the worst times, when prison expansion was off the charts; we built 20 prisons in 20 years — here we were, a few hundred, mostly life prisoners, caring about the health, the welfare, and safety of thousands of women in the state. And CCWP never folded.

Lanie Greenberger: This motto, “caring collectively,” has special meaning to me as over the years I have observed/participated in campaigns wherein CCWP put forth the effort to represent all of us collectively. From those housed in Ad-Seg/SHU [Special Housing Unit] to transgender people to those suffering [from] mental illness and battered women. At no time did CCWP look the other way or think any challenge was too big or too small for their care. I must applaud CCWP’s collective dedication to those of us serving LWOP sentences. When others simply dismissed us, CCWP took the bull by the horns and never let go until they succeeded. Conversation was opened and minds changed. Ultimately, LWOPs were commuted and released in numbers never imagined.

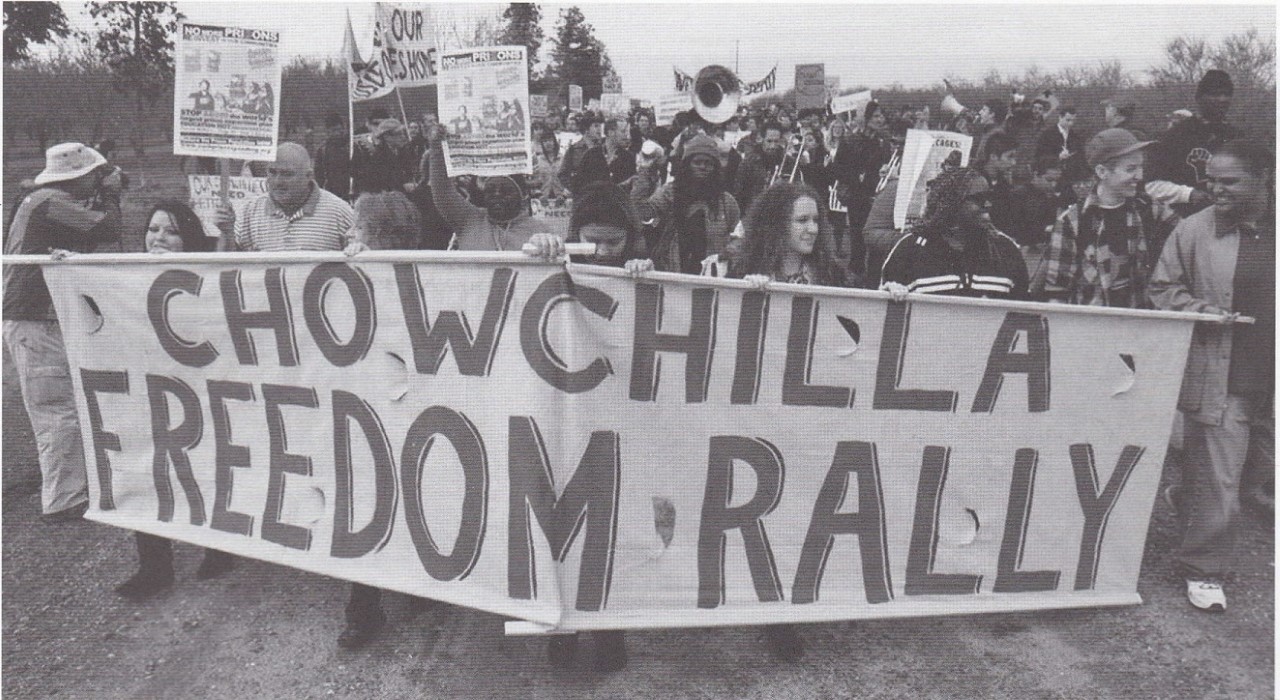

Tien Mo: “Caring collectively” is believing we are a part of something. We are bigger, stronger, more diversified, and simply better when we look at and care for one another. Alone, I am just a grain of sand, but all together, we can be the beach, withstanding whatever waves the ocean throws at us. CCWP embodies this. CCWP fights for the ones that are forgotten, the ones deemed unsavable by the system, trusting in the “we” versus the “I” concept. Being an LWOP, CCWP has advocated for me at various #dropLWOP rallies. I have been represented with letters, photos, banners, etc. The criminal justice system says “Lock her up and throw away the key!” But CCWP, along with our voices, refutes that notion. We, as a collective, will not stand down.

Alone, I am just a grain of sand, but all together, we can be the beach, withstanding whatever waves the ocean throws at us.

Hamdiyah Cooks-Abdullah: It means that together, those of us who’ve experienced incarceration and those of us who haven’t, have the opportunity to support each other in ways that wouldn’t be possible if we didn’t care collectively. One of the memories that stands out for me that reflects the term “caring collectively” was one of the rallies we conducted outside of VSPW where an incredibly diverse group of us rallied around inadequate health care. We chartered a bus and rode together to support people inside. Once the rally began, we had a marching band leading us and the sisters inside all together, shouting through the walls in one voice, “We will be free!” This hope for freedom still lives in me almost 15 years later.

Copyright © 2022 Emily L. Thuma and Joseph Hankins. This excerpt originally appeared in Abolition Feminisms Vol. 1: Organizing, Survival, and Transformative Practice edited by Alisa Bierria, Jakeya Caruthers, and Brooke Lober. Published by Haymarket Books. Reprinted here with permission.

Introductory essay written by Emily L. Thuma, Romarilyn Ralston, and Joseph Hankins.

Header image: Brian Garcia/Unsplash