In Body and Soul, a pathbreaking examination of the Black Panther Party’s abiding commitment to health activism, Alondra Nelson recounts how Bobby Seale, Huey Newton, and other party leaders came to prioritize the pursuit of health and healing as vital to their survival—in more ways than one. As the Panthers’ reputation for armed resistance to police violence—and demands for a society that left no Black or poor people behind—grew in the public eye, so did their criminalization, incarceration, surveillance, and even death at the hands of state actors. Combined with disenchantment with the insufficient civil rights gains of the 1960s, evident in the enduring precarity of the so-called war on poverty, the party bolstered its focus on a key aspect of its platform: their people’s health. Serving the people, body and soul, became ever more central to the Panthers’ organizing, message, and the future they wished to see.

Understanding this “revised narrative” of the Panthers, as Nelson calls it, helps contextualize how the party went on to establish, among other imperatives, a nationwide network of free-for-all health clinics—the People’s Free Medical Clinics. In these “alternative healthcare facilities,” patients were offered care at no cost, found safety from medical discrimination, received political education, and had other needs met by trusted health experts and laypeople alike. Importantly, the Panthers recognized that social health—that is, the community’s broader well-being—called for more than simply health-care access. “Local residents could receive assistance from a ‘patient advocate’—a Party member or volunteer—on such matters as physical health, housing issues, and legal aid,” Nelson writes. “In this way, the clinics were also bases of operation for the Panthers’ wider ‘serve the people’ agenda.” Like the Panthers’ free breakfast for kids program, the clinics were both sites of service and a way of doing politics by other means.

The Black Panthers did not speak the language of abolition the way prison and police abolitionists speak it today. Neither were they trained public health practitioners in the traditional, institutional sense. The opposite is true: The nation’s long history of medical mistreatment of Black and marginalized people, and the Panthers’ own reservations about the medical establishment, turned them into health intermediaries—a bridge between allied medical professionals and community members, whose lived experiences and insights into their own condition were deemed just as valuable.

Pointing to this record of community care, Zahra Khan, Yoshiko Iwai, and Sayantani DasGupta have placed the Panthers’ model within a tradition of “care structures that have historically operated at the margins.” Like the Young Lords in the 1960s and ’70s, who likewise saw the health of Puerto Ricans in the Bronx as integral to their collective survival, these revolutionaries’ health activism and organizing serves as a model today for a new generation of abolitionist public health workers, academics, students, researchers, community organizers, and allied medical professionals. Together, these advocates strive to take a broad view of what constitutes the public’s health—and the need to disentangle it from the practices that feed mass incarceration.

“There are powerful traditions and lineages to build on and learn from, and there is much to be gained by studying about these lineages as we struggle together,” Maria Thomas, an organizer with Interrupting Criminalization’s Beyond Do No Harm initiative, wrote in the Forge in September.

Beyond Do No Harm, whose overarching goal is to end the criminalization of patients while they’re seeking care, is but one network from a growing list of organizations that want the field of public health to be in firm alliance with the movement to end the harms of policing and prisons. Whether formal or informal, these alliances are already taking root. From Los Angeles to Kentucky to Atlanta, more and more advocates are adopting abolitionist frameworks, backed by public health research and medical expertise, as they oppose projects that would harm rather than heal their communities.

At its core, abolitionist public health sees carceral institutions and practices as antithetical to public health. If jails, prisons, and detention centers are death-making by nature, as Mariame Kaba has famously observed, then it follows that the public’s health is ill served by continuing to invest in carceral structures that make people and their communities sick, as abundant research has shown.

Yet traditional public health has been slow to catch on to this reality, in part because, for much of its history, the field has acted as the eyes and ears of the state in health-care settings. Many people in this space—which encompasses government, academic, nonprofit, and private sectors—have told me that the field of public health, despite recent advances, remains conservative and connected to systems of coercion and control. “Public health is a tool of the state to maintain order,” Bita Amani, a social epidemiologist at Charles Drew University’s Department of Urban Public Health, told me in an interview. In her work, Amani takes the long view of U.S. public health, which she says arose to compensate for the absence of socialized, universal health care in the United States and other public measures that keep people healthy.

From the series

Abolition in Action

A collection of essays exploring how people are practicing abolition in their communities, in partnership with Truthout.

This form of organized abandonment, which has been filled with the corporatized, commodified health-care system that exists today, has resulted in a medical profession that lacks training in social medicine—a glaring omission that helps explain why health-care settings, especially in areas where the need is greatest, have become enmeshed with other systems of social control. Indeed, public health institutions have a record of being complicit, if not willing participants, in treating public health problems with carceral interventions. From the drug war to the crisis of gun violence to the management of COVID-19, the threat of punishment and incarceration remains a favored tool to ensure compliance. Until recently, even migrants were subject to swift deportation thanks to a public health emergency measure supposedly intended to prevent the spread of communicable disease.

Abolitionists in public health have been working to stem this tide. The End Police Violence Collective, which organized members of the American Public Health Association (APHA) to draft and adopt a policy statement naming the harms of carceral systems as a public health crisis, had to work hard behind the scenes to educate skeptics that abolition and public health are, in effect, two sides of the same coin. “Far from destruction,” the collective wrote for Inquest in 2022, “abolition is about disrupting systems that create or compound harm, while establishing or reinforcing health-affirming ones in their stead—ultimately creating a world where people have what they need to live healthy and safe lives in their communities.”

The APHA statement has become an advocacy and organizing tool of its own. Advocates in New York City have cited it to push for public health approaches to violence prevention. In Ohio the statement has been used in policy analysis to uplift the health benefits of moving away from pretrial incarceration in the state. In Texas a policy brief for the city of San Antonio advanced public safety solutions outside of arrest and incarceration, relying on the APHA statement for its recommendations. And in Massachusetts multiple organizations signed statements or letters of support citing the statement, calling on the legislature to pass a bill imposing a moratorium on new prison and jail construction projects. (A pre-2020 APHA statement naming police violence as a public health issue did not raise abolition as a solution, but the George Floyd uprisings gave organizers an opening with APHA voting members the second time around.)

Within the U.S. government, the World Health Organization (WHO), and state and local public health authorities, there is widespread acceptance that preventing disease and death by addressing the “social determinants of health” is a cornerstone of public health. These determinants, which can mean the world to people who lack them, include economic resources to meet everyday needs, such as nutritious food, housing, and transportation; quality education and job training; access to health care; clean air, water, and access to public spaces; and an environment free of state violence. Failing to fund these priorities, the thinking goes, leads to failed societies. “Social injustice,” the WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health noted in a 2008 report, “is killing people on a grand scale.”

Despite this knowledge base, federal, state, and local governments’ investments in policing and prisons continue to outpace social welfare programs. Yet social welfare programs have been shown to prevent criminalization, contacts with the criminal legal system, and reincarceration. And public health spending in particular, by one measure, accounts for a measly 1 percent of all health-care spending in the United States.

At the instructional level, meanwhile, public health education isn’t quite moving the needle. Writing in Health Education and Behavior, a group of former and current public health students from different institutions contended that public health education does not interrogate the underpinnings of what abolitionists call the prison–industrial complex, let alone its public health impacts or how the field is routinely in cahoots with carceral actors. Maya Talwar-Hebert, a graduate student and organizer at the Columbia Mailman School of Public Health, echoed some of these critiques when asked if her school offered an abolitionist curriculum to support her own work. “The school seems to recognize policing and incarceration as public health problems, but remains committed to reformist frameworks to address them,” she wrote in an emailed response.

Carlos Martinez, who teaches at UC Santa Cruz and coedited the forthcoming collection All of This Safety Is Killing Us: Health Justice Beyond Prisons, Police, and Borders, noted that there’s a tendency in public health instruction to remain “individualist”—placing the onus on individuals rather than systems to improve health outcomes. “The way that public health is taught in most programs continues to be focused on individual behavior change instead of systems change, even as concepts such as social determinants of health have entered the mainstream,” Martinez said in an email. He pointed to a study showing how public health textbooks, almost without exception, are framed around “behavioral fundamentalism”—the idea that health is guided by behavior and personal choices rather than social, structural, or systemic factors.

Human Impact Partners (HIP), in Berkeley, California, is an organization with its finger on the pulse of all these conversations around the intersection of public health and abolition. Its mission is to transform the field of public health from the ground up. By centering equity and building collective power with social justice movements, the organization envisions a future where everyone has everything they need to thrive, and where public health “upholds policies, practices, and systems to ensure health and well-being for those who need it most.”

HIP does this work in a number of ways. A capacity-building team works with governmental public health organizations, like the National Association of City and County Health Officials, leading trainings and providing technical assistance on how to center racial justice and health equity in their work. A bridging team connects these officials to community-building organizations, to help them align their goals and practices. And a policy and organizing team supplies grassroots organizations with research support for their policy and budget campaigns. “I think of what we do as providing community orgs with another tool in their toolkit as they are running their campaign,” Christine Mitchell, who leads HIP’s Health Instead of Punishment Program, told me.

As Mitchell recounts HIP’s history, the organization wasn’t always explicitly abolitionist, opting instead for partnering with others who wore the label. But in 2019 its leaders decided that it was time to be open about it, because there weren’t—and still aren’t—many organizations in the public health realm that are explicitly abolitionist. “That’s kind of a little niche that we were able to fill,” Mitchell said. “I think we see abolition as fitting very neatly into the mission of public health—that abolition is a public health strategy.”

“We are lucky to have funders that don’t see that as a problem,” she added.

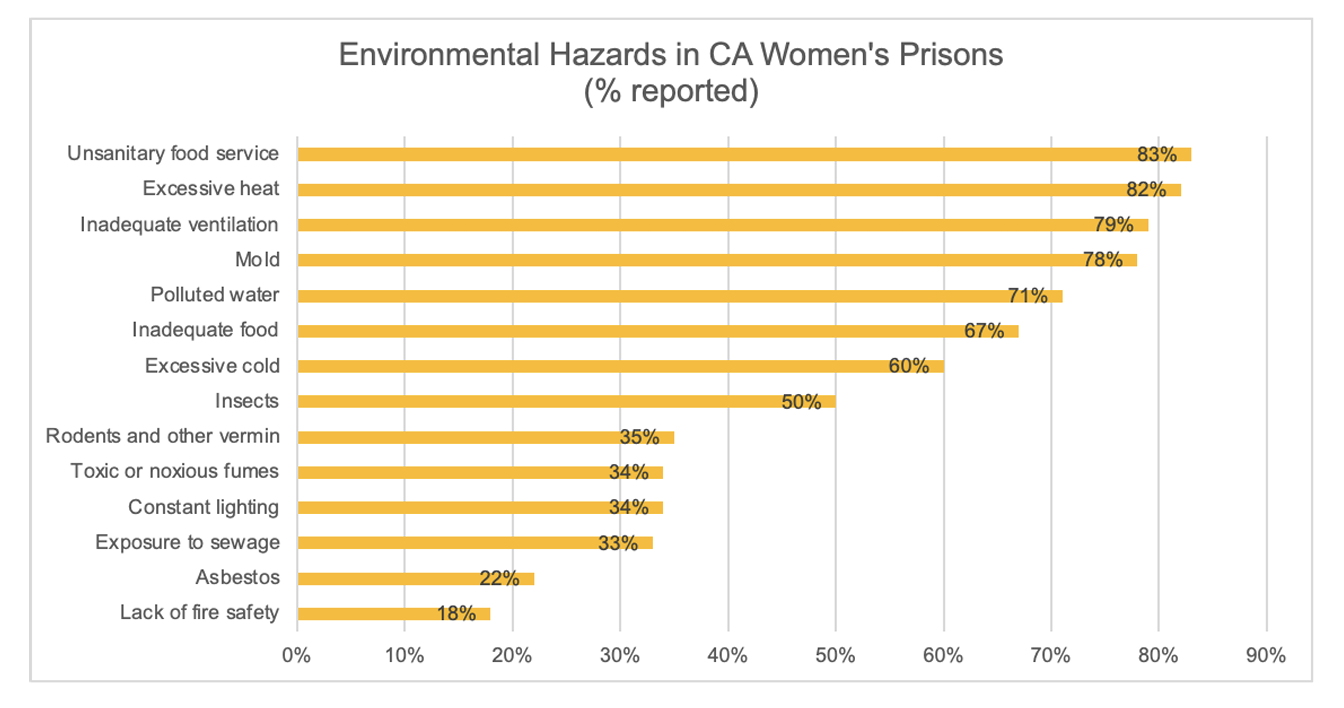

One campaign that has benefited from HIP’s expertise is the ongoing push to close the last two women’s prisons in California. Together with its partners, the California Coalition for Women Prisoners (CCWP), as well as Californians United for a Responsible Budget and the Transgender, Gender-Variant, and Intersex Justice Project, HIP developed a report, backed by extensive public health research, laying out the lasting harms of women’s prisons—and the need to invest in materially supporting the people directly impacted by them. Mitchell said that currently and formerly incarcerated people who have been caged in the prisons targeted by the campaign took part in both the qualitative and the quantitative research that went into the report, and HIP ensured that its framing uplifted their stories and experiences.

This approach is not unlike what the Black Panthers did by allowing everyday people to claim their own expertise and take an active role in shaping their own conceptions of health, creating valuable knowledge that others could use. Nelson calls this the “democratization of expertise.”

In this vein, Jane Dorotik, a formerly incarcerated member of CCWP’s coordinating committee who spent twenty years in one of the prisons targeted for closure, said she values the public health perspectives that HIP brings to their organizing, but also appreciates how her own expertise is valued. She recalled a recent public health convening in the Bay Area, to which HIP invited her as a panelist, and how the people in the room did not quite see jails and prisons as harmful to public health. “A lot of them don’t necessarily think of incarceration as a public health crisis,” Dorotik, who has a background in nursing, told me. “And we have to start thinking that way so that we can turn things around.”

Once a finished report sees the light of day, Mitchell said, HIP will remain engaged with the broader campaign—whether in the form of legislative testimony, letter writing, or other support organizers may need. “The partnership doesn’t end when the product is out,” Mitchell said, contrasting it with how academic research tends to leave its subjects behind once the findings are published.

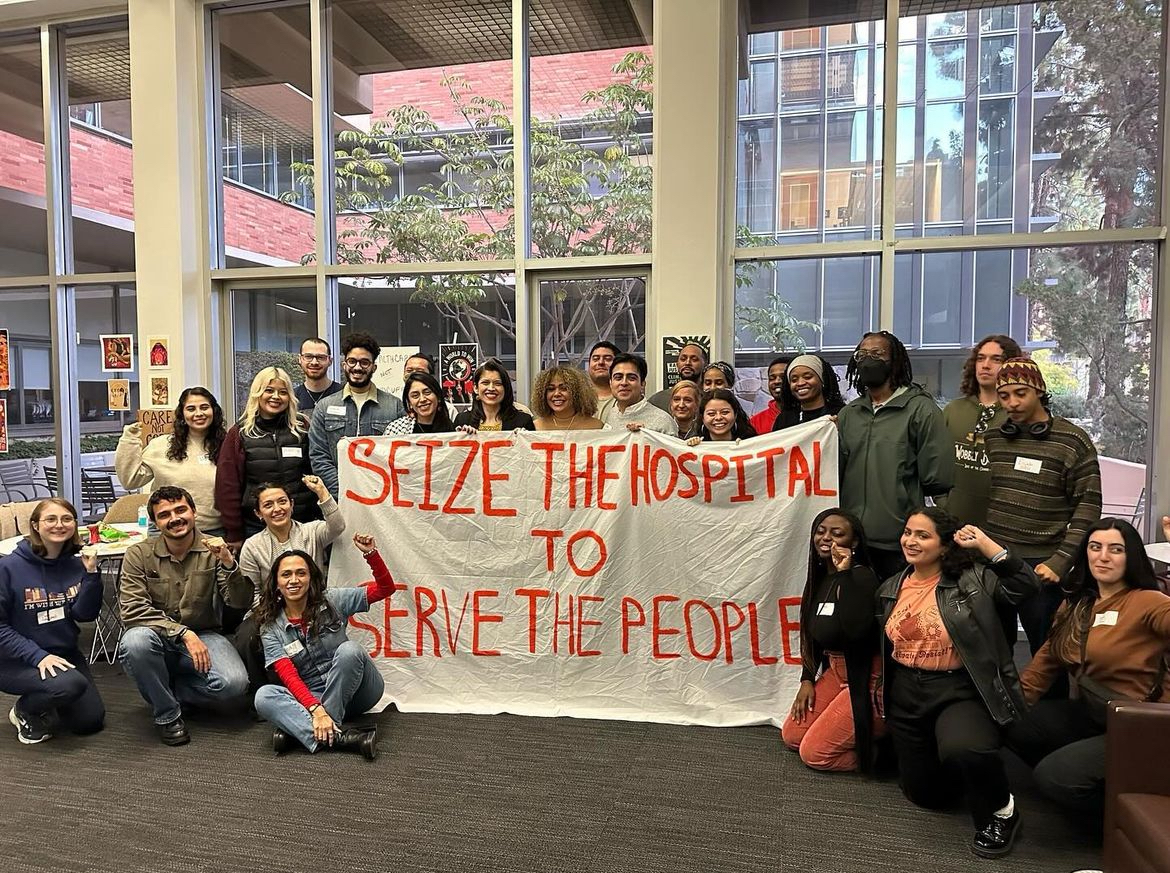

HIP is also cultivating future public health leaders through its Abolitionist Public Health Student Network. Since the spring of 2022, a number of semester-long “cohorts” from various schools have joined the network to learn and organize together, with the goal of building community, strategizing, and staying connected long after members have entered the workforce. Melina Rodriguez, who attends the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health and organizes locally with the Health Not Punishment Collective, told me in an email that the network has served as a reminder that “you are not alone” in work that sometimes can feel “daunting” and “heavy,” in part due to what feels like insufficient institutional support. “I don’t think that I would have started up Health Not Punishment Collective had it not been for this community that taught me so much about how to do it, and served as a constant reminder that we could do it,” Rodriguez wrote.

Amani, the social epidemiologist, told me that despite the many structural headwinds U.S. public health and the broader health-care system face, she feels that the younger generations—the public health practitioners being trained and entering the field today—are far more sophisticated and attuned to what needs to change. “I don’t know of any societal transformation, revolution, or major reform movement anywhere that did not have involvement of people that were in public health and health,” Amani said.

Mitchell, for her part, says with a laugh that her hope is to live in a world where HIP is not needed because people will have all their basic needs met. “I want to work myself out of a job,” she said.

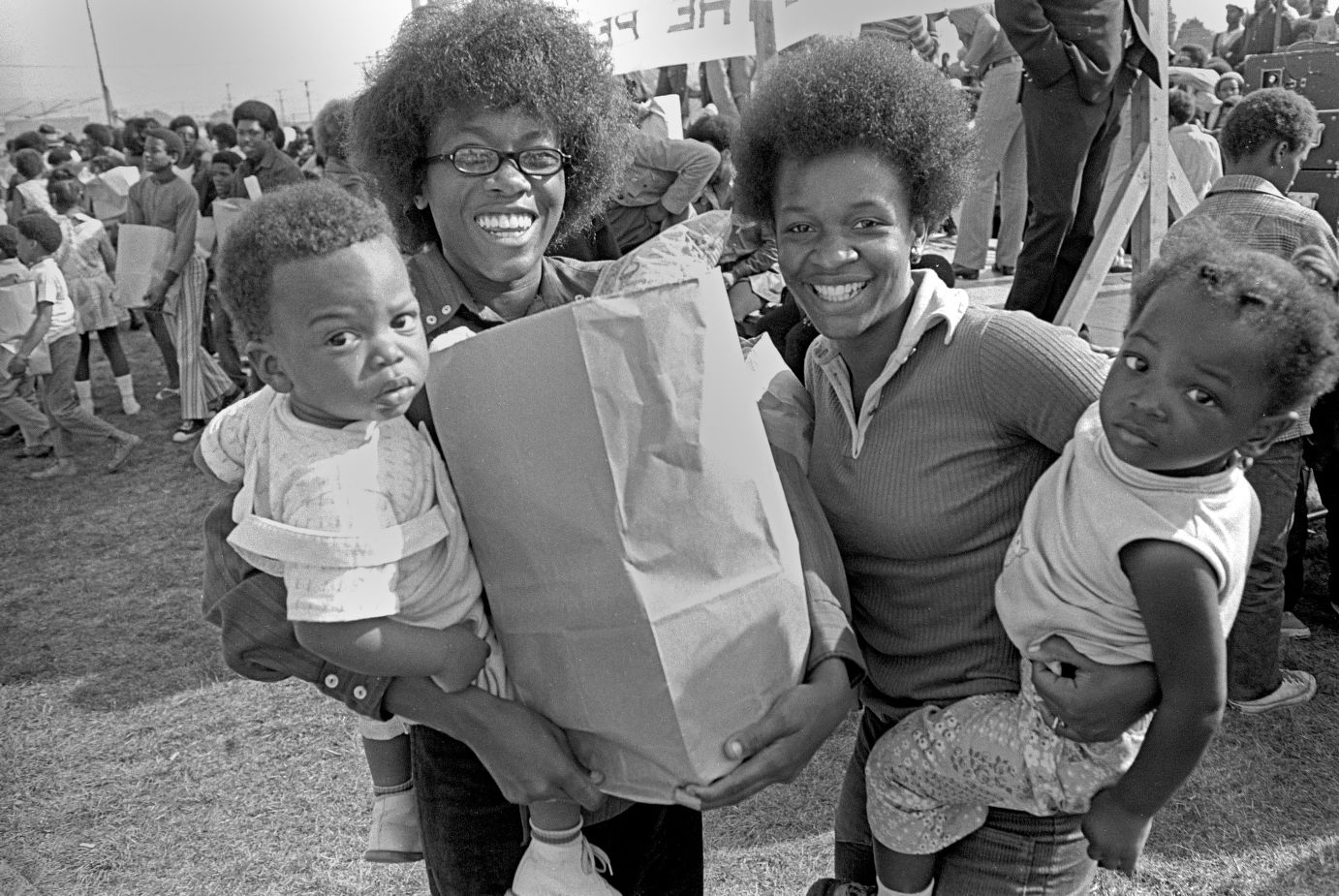

Header image: Free sickle cell anemia testing at the Black Panther Party’s Black Community Survival Conference on March 30, 1972, in Oakland, California. (Bob Fitch Photography Archive/Department of Special Collections/Stanford University Libraries)