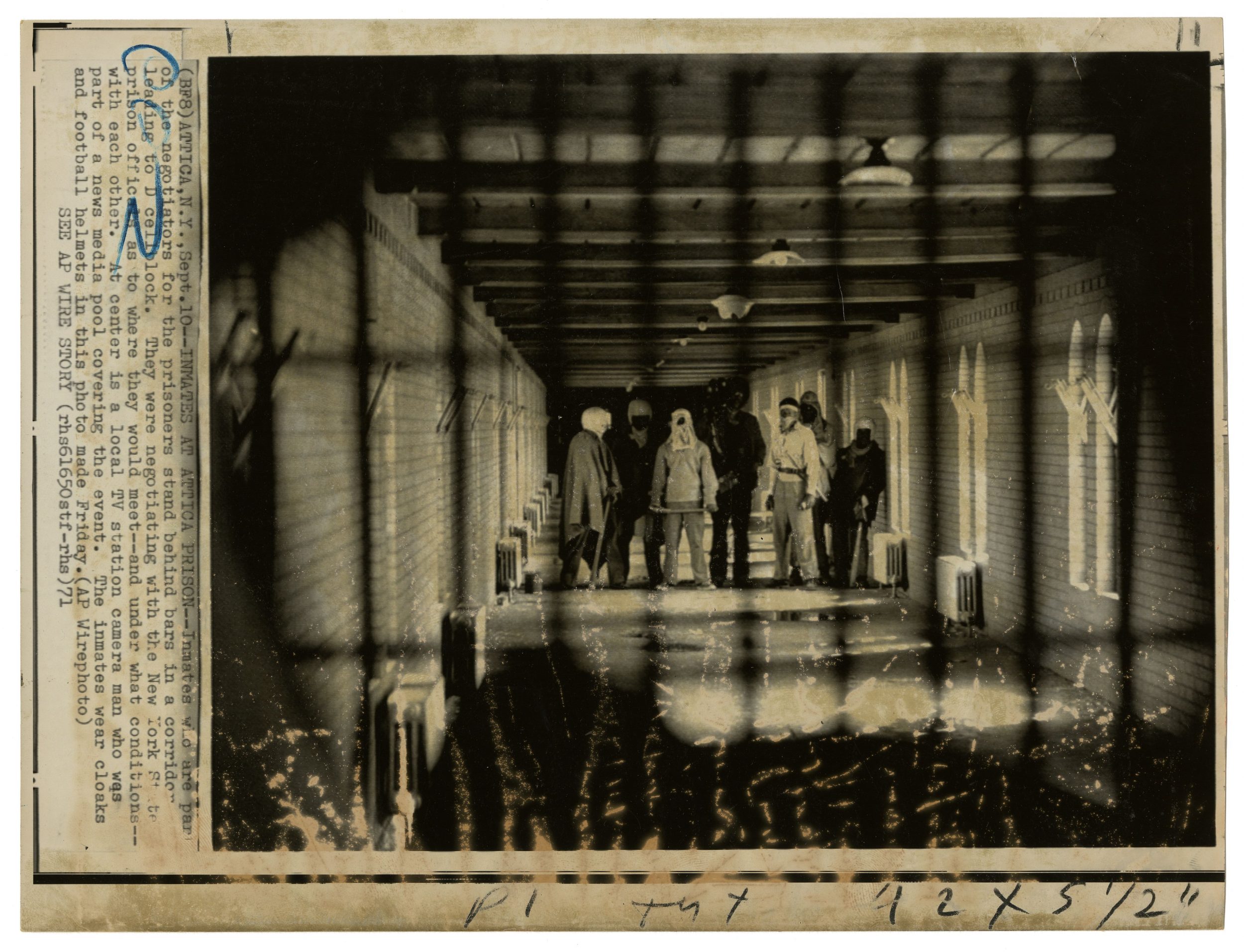

Dominant narratives frame the Attica Rebellion at New York’s Attica Prison as having been crushed after September 13, 1971, when a state assault force opened fire on the prison, killing twenty-nine rebels and ten prison guards. Yet the events of those five days are only a piece of a protracted struggle, which preceded the Attica Rebellion and endured after the state-orchestrated massacre. During the 1970s, organizers of what I term the “Long Attica Revolt” asserted a diverse array of demands. On the one hand, they articulated a revolutionary abolitionist vision that is irreducible to prison reform. On the other hand, throughout this interlinked series of rebellions in the New York City jails, as well as at Auburn and Attica prisons, incarcerated people and their loved ones enunciated and struggled over pragmatic demands to improve violent prison conditions.

The tension between the urgent need to secure reforms to enable captives’ immediate survival and the equally urgent project of abolishing broader systems of oppression is a central contradiction of the prison movement, and of the broader Black liberation struggle. While ameliorating harm provides essential relief for those enduring it, such relief can have a stabilizing effect on the predatory systems that generate harm in the first place. At the same time, those who engage in militant attacks against the system inexorably face the wrath of the state, often resulting in a painful existence and a premature death.

This internal tension and its implications were on full display during a public hearing of the New York State Select Committee on Correctional Institutions and Programs. Governor Nelson Rockefeller had launched this committee in the weeks after he authorized the September 1971 massacre, a shrewd political move to generate bipartisan support for his prison reform agenda. This panel of so-called experts—lawyers, political elites, and prisoncrats—triangulated the security requirements of the state with carefully selected rebel demands, proposing an array of reforms to “modernize” the prison system “even in light of the State’s current serious fiscal situation.” Among them were the construction of new prisons, especially at the minimum- and medium-security levels; improvements to visitation policies, medical care, and the overall institutional “atmosphere”; the implementation of new rehabilitative programs; and the development of “classification capability for determining the types of programs and security needs of the individuals under custody.”

On February 11, 1972, survivors of the Attica and Auburn rebellions, as well as their family members and supporters, all organized under the banner of the Prisoners Solidarity Committee (PSC), traveled to downtown Manhattan to force their critiques of these proposals into the public record. Their continued defiance in the face of state power demonstrates that the Long Attica Revolt had survived the massacre. However, it also revealed the movement’s ideological and tactical heterogeneity, a condition that state actors sought to exploit.

The PSC’s bold intervention violated the protocols of courtroom decorum. Tom Soto, who had been in Attica during the rebellion as an outside observer, interjected from the audience.

At this time I would like to state now behind me are Lawrence Killebrew, who was shot three times in Attica, who was marked with an X on his back; and I have on my left Sharean of the Auburn 6 [six captives criminally charged for their role in the Auburn rebellion] who was also in Attica during the rebellion who was gassed at one time for seventeen hours, has been beaten in courtrooms while in chains and shackles and handcuffs; and we also have Carmen Garrigia, the wife of a relative in Attica who was also abused and brutalized. I believe that they should be the next ones to testify.

Soto’s brazen introduction of people directly targeted by carceral violence ruptured the progressive facade of the Select Committee, which “was set up as a result of Attica,” according to internal documents, but managed to avoid referencing the rebellion or the massacre in its initial report. After a heated argument between Soto and the Select Committee’s chairman, multiple scheduled speakers ceded their time, allowing the PSC to testify.

While the first two speakers described the shocking forms of sexual racism they endured in Auburn and Attica, Garrigia discussed the subtle and mundane forms of abuse the system inflicted on her whole family. She explained that her husband, James Walker—also a survivor of the Auburn and Attica rebellions—should have been standing by her side, but that, on multiple occasions, his expected release date had been pushed back due to infractions accrued in connection with the rebellions. She further explained that prisoncrats were heavily censoring letters between her husband and their daughter and that, because the Department of Corrections had few Spanish-language translators, weeks often passed before their letters were delivered. Garrigia outlined the significant costs associated with the eight-hour bus trip from New York City to Attica and inveighed against the invasive searches she endured before and after each visit, explaining how she and her husband tried to maintain some semblance of intimacy by poking their fingers through the wire screen that separated them during visits. She was incensed by the arbitrary restrictions on the kinds of items she was allowed to leave with her husband during these visits. “You can’t send honey in,” she explained. “They are not allowing toothpaste in there, no fruit juices. How are they supposed to supplement their diet?”

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

Garrigia’s efforts to keep her family whole, maintain an emotional connection with her husband, and introduce items of care that might momentarily sweeten his existence highlight the key role that outside communities, especially women, played in ensuring the survival of those inside. Speaking from her position as caretaker of the family, her testimony challenged the Select Committee’s vague language on reforming the prison “atmosphere.” Instead, she called for the immediate amelioration of specific material conditions and policies that circumscribed the humanity, dignity, and collective survival of targeted communities. Rebels articulated this category of demand throughout the Long Attica Revolt, from the New York City jail rebels, who demanded “as human beings, the dignity and justice that is due to us by right of our birth”; to the Auburn demand for Black Studies programs; to “The Fifteen Practical Proposals” the Attica rebels authored after being told that their “Immediate Demands” were unrealistic.

Although achieving “wins” among this class of demands is critical to the long-term sustainability of movements unfolding under conditions of genocide, their pragmatism rendered them vulnerable to co-optation. To co-opt, argues sociologist Robert L. Allen, is “to assimilate militant leaders and militant rhetoric while subtly transforming the militants’ program for social change into a program which in essence buttresses the status quo.” As overarching logics of the state counterinsurgency against the prison movement, psychological warfare and co-optation intentionally muddled distinctions between victories and defeats. In the words of the U.S. Army’s Counterinsurgency Field Manual, “Skillful counterinsurgents can deal a significant blow to an insurgency by appropriating its cause.”

Testifying directly after Garrigia, Joseph Little exposed the imperialist logic undergirding the Select Committee’s proposals. Discharged from Attica’s hellish walls just ten days earlier, Little excoriated reform and rehabilitation as modes of domination and lambasted the gathering as a “farce.” Its so-called experts, Little noted, were regurgitating “the same old bullshit” that prison reformers had been spouting for over a century. Although he could produce “a long dissertation” on the brutalities of prison, however, he was not among the growing chorus of people demanding ameliorative reforms: “Everybody wants to get on the political bandwagon. Everybody is down with penitentiary reform. Let us make the penitentiary like the Holiday Inn. I’m not for no penitentiary reform. I am for abolishing the whole concept of penitentiary reform.”

Long before abolition was in vogue, Little articulated an abolitionist critique, voicing principled opposition to ameliorative reforms based on an understanding that they would extend the prison’s life. His analysis anticipated and radicalized French theorist Michel Foucault’s oft-cited observation that prison reform is a constituent element of the prison itself. Not only did Little diagnose the centrality of reform to the prison’s core functioning; he asserted a demand for the abolition of reform, which is to say the abolition of the prison itself. As dutifully captured by the court stenographer’s transcript, Little’s statements elicited applause from the audience.

Little then denounced “rehabilitation” as propaganda, a disguised attempt to “pacify the inmates,” “make them docile citizens,” “train them to be like robots,” and mold them according to white, ruling-class values.

Am I to be rehabilitated to be like who? To be like the racist guards, the racist administrators who are running this country? To be like Rockefeller? Or the Mellons or any other ruling class? Am I to be like you gentlemen sitting there? Just what constitutes rehabilitation? There is nothing wrong with me. What needs to be rehabilitated is the society we live in.

His interrogatory critique inverted standard criminological analytics, which trace criminality to biological, psychological, or cultural defects believed to be internal to those who transgress the law. To the contrary, Little contended that the structure of society is defective, that social life is afflicted by capitalism and white supremacy. In his view, if the committee were truly interested in eliminating violence and crime, they would attack these systems of power, for they produce what Little called a “dog-eat-dog society,” a society that requires crime and prisons.

In a 1973 address to the Fraternal Order of Police, Democratic congressman Richard H. Ichord described an ongoing investigation by the House Internal Security Committee, of which he was chairman, in the following way: “Our committee has also been conducting a wide-ranging inquiry into the exploitation of prison conditions and unrest by revolutionary groups and organizations in an effort to recruit from behind prison walls and with the aim of tearing down the administration of the penal system as a prelude to destroying the institutions and form of our entire government.” Little’s unapologetically abolitionist demand for the overturning of the political–economic structure of society is more compatible with this often-dismissed theory than it is with liberal reformist analytics that focus on prisoners’ rights. Many of the revolt’s combatants, engineers, and elected spokesmen saw themselves as the tip of a revolutionary spear and engaged in anti-carceral insurgency with capacious ambitions in mind.

Recognizing the implications of Little’s testimony, the vice chairman of the Select Committee asked Little if his political analysis was shared by others. “When the problems at Attica arose, were the people at the proper front of that particular movement fighting for the things that you mentioned before in your testimony? The complete change and not interested in the superficial change that perhaps might have been recommended in a report like this?” he asked. Little neither confirmed nor denied the revolt’s revolutionary impulse. Although he and a few others were now outside the prison walls, they remained targets of carceral state repression. Jury selection in the long-delayed trial of the Auburn Six had just commenced, and the state’s criminal investigation of the Attica rebels was developing rapidly. Moreover, in one of his last public statements before his sudden death, J. Edgar Hoover raised the specter of an “unholy alliance” between “black hardened criminal prison inmates” and “black revolutionary extremists.” Hoover’s secret program to “neutralize” these imprisoned revolutionaries would soon evolve into the Prison Activists Surveillance Program.

It would have been reckless for Little to elaborate on the revolutionary underpinnings of the Attica rebellion within this context of intensifying repression. “It seems as though you might be trying to bait me into [admitting] that I am advocating the overthrow of the government, or something like that . . . but I am no fool,” he replied. Little knew state actors were looking for any excuse to further criminalize and pathologize the rebels, which made it tactically necessary for him to deemphasize Attica’s revolutionary politics. Such concealment and obfuscation are central to the conduct of revolutionary warfare. Unfortunately, most scholars and analysts have overlooked this point, taking its outward focus on formal demands at face value. In doing so, they have unwittingly reinforced the reformist counterinsurgency project.

The approaches represented by Garrigia and Little are not necessarily antagonistic. Rather, they existed in productive tension within the PSC, an explicitly abolitionist formation launched by “free world” organizers in support of the Auburn rebels. The same tension existed within individual organizers as well. Throughout the 1960s, imprisoned revolutionary Martin Sostre and others launched several successful lawsuits that legally compelled prison authorities to ameliorate dehumanizing conditions. And yet these conditions endured. In “The New Prisoner,” an acerbic essay published in 1973, Sostre asserts that Auburn and Attica represented “decades of painful exhaustion of all peaceful means of obtaining redress, of the impossibility of obtaining justice within the ‘legal’ framework of an oppressive racist society which was founded on the most heinous injustices: murder, robbery, slavery.” For Sostre, the fact that what he called the “Attica Reform Demands” were aimed at many of the conditions that his successful litigation should have already resolved demonstrated that captives had no choice but to rebel, seize hostages, and adopt a more revolutionary posture. Sostre saw value in reform and abolition demands, particularly when they were grounded in a revolutionary critique of the social order.

Excerpted from Tip of the Spear: Black Radicalism, Prison Repression, and the Long Attica Revolt by Orisanmi Burton, published by the University of California Press. © 2023 by Orisanmi Burton.

Image: New York State Archives