In 2016 a small group of base-building organizations, faith leaders, policy experts, service providers, lawyers, and abolitionist community organizers came together to identify and support people in Cook County jail suing the Cook County criminal court system for its unconstitutional use of money bond. We named ourselves the Coalition to End Money Bond, and seven years later we’ve done just that.

On September 18 of this year, Illinois implemented the Pretrial Fairness Act, and for the first time in our country’s history, a state has fully stopped charging people money to return to their communities while they await their day in court. Families are no longer being forced to choose between paying rent or paying a ransom to bring their loved ones home. No longer are people losing their jobs or housing simply because they are too poor to pay a money bond. People are no longer facing pressure to take plea deals because they cannot afford to purchase the presumption of innocence—supposedly one of our most basic rights.

From the beginning, the coalition’s work has employed inside and outside game strategies. It was our belief that everyday people coming together in the streets can change what is possible inside the halls of power, whether that be a courtroom or our state capitol. It was important to our organizing strategy that we included organizations that subscribed to different theories of change but were willing to come together under a big tent.

My colleague, Sharlyn Grace, previously outlined in Inquest our theory of change and the organizing lessons we learned over the last seven years. Over time, those strategies expanded as we grew into a statewide coalition and as some of our members began to take on roles within government—even as county and state government officials. Former coalition members worked on the governor’s and lieutenant governor’s policy staff at important junctures in the campaign. Today, former coalition members include a state senator, Chicago’s deputy mayor for community safety, and the public defender for our state’s largest county court system.

Working in conjunction with, and as a part of, abolitionist mass movements for racial justice, we were able to not only change what was possible, we made the impossible a reality. In what follows, I provide a snapshot history of our campaign’s work before turning to an exploration of the challenges we continue to face as opponents of ending cash bail continue to challenge the law’s implementation.

On May 13, 2016, our budding coalition met for the first time in a building owned by Northwestern University’s law school. While advocates, legal experts, and community organizers brainstormed what type of change was possible and what the goals of our collective work would be, Lavette Mayes was locked in a cell inside Cook County jail.

May 13 wasn’t a special day for Mayes. In fact it wasn’t much different than the 568 days that had come before it. For more than a year and a half, Lavette had been incarcerated while awaiting trial. After being arrested, she was taken to Cook County’s central bond court and put through a process she likened to being auctioned. Dozens of people, predominantly Black, were lined up and brought into the courtroom where a judge quickly assessed them with money bonds and sent them to be processed into the jail. At the time, some 70,000 people were being booked into Cook County jail each year. They were disproportionately Black, and a majority of them were jailed only because they couldn’t afford to pay their bonds.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

The judge had set Lavette’s bond at $250,000, meaning she would need $25,000 to return to her two children. It was an impossible amount for her family. Lavette’s life on the outside quickly began to fall apart. She lost her home, business, and nearly lost custody of her children. Like so many others, Lavette wasn’t being jailed because the court believed she was a danger to anyone. She was being caged because she couldn’t afford the price placed on her freedom. A few months later, Lavette’s bond would be reduced to $100,000—but by that time, her family had spent through her savings paying for a private attorney, putting money on her commissary, and covering childcare expenses.

Two years later, on a warm September morning, Lavette stepped up to a microphone outside of a building in Chicago’s Loop that houses Illinois state government offices to tell her story. She spoke of the harm wealth-based jailing had caused her family, how the Chicago Community Bond Fund had worked with her family to bring her home, how she had been shackled with an electronic monitor, how she ultimately took a plea deal to end the nightmare her family had been put through, and how she had decided she was going to do everything she could to make sure no one else would experience what she had gone through.

More than a hundred people gathered that day to mark the one-year anniversary of General Order 18.8A, a court rule issued by Cook County chief judge Timothy Evans. The order was issued in direct response to the lawsuit that initially brought our coalition into formation. Chief Judge Evans had instructed his judges to only set money bonds in amounts that people could afford, essentially creating a local process for following existing statutes long ignored in courtrooms across the state.

On the first day of the order’s implementation, September 18, 2017, organizers from our coalition sat in bond court and listened as the judge asked each person how much they could afford to pay. Then, in many instances, the judge still set a money bond above that amount, effectively making de facto detention orders. Although we were not surprised, the resistance to the order was still disheartening.

Fortunately, we had the foresight to predict this and had been training people to watch bond court in the months prior to implementation. Dozens of people gave their time to observe these hearings, collectively sitting in court for hundreds of hours recording the outcome of every case. The data they collected was used to raise public awareness of the fact that judges weren’t abiding by the court’s order, state law, or federal constitutional standards. Ultimately, the public pressure campaign that came out of this court-watching initiative helped force the proper implementation of the order in many courtrooms. Our organizing efforts resulted in the number of people caged in Cook County jail dropping by more than 2,000 people. Six years later, it has amounted to some 60,000 fewer people being subjected to the unsanitary and brutal confines of Cook County jail.

Knowing that the general order wasn’t going to actually end money bond in Cook County, let alone Illinois, our coalition had already begun pivoting to put pressure on the state Supreme Court to issue a rule change that would have mirrored the reform in Cook County. Simultaneously, we filed legislation to end money bond in our state legislature. We hoped this legislation could act as a North Star if the legislature decided to act, but we knew we did not have the power to control the debate. It was a lesson learned from closely watching as our allies in California had their legislation to end money bond chopped and skewed to become something so disastrous, they would ultimately work alongside the bail bonds industry to repeal it. While advocates everywhere want to end money bail, it was much more important to us all that the undoing of this archaic system did not give birth to something much worse.

After months of pressure, the Supreme Court announced it would form a two-year commission that would evaluate whether or not reforms to the pretrial system were necessary. The commission was to be made up of judges, prosecutors, law enforcement, legislators, and a public defender. Impacted communities were not to be a part of this conversation that would take place behind closed doors. The formation of this commission provided the momentum we needed to take a big step forward and take our campaign statewide and form the Illinois Network for Pretrial Justice.

Over the course of several weeks, we traveled across Illinois meeting with organizers to learn about how pretrial jailing was impacting their communities, the work they were doing, and to discuss how we might be able to work together to end money bond.

As someone who learned to organize in Chicago, I expected that there would be a lot of pushback from people telling us our well-meaning proposals were too drastic. Instead, in cities and small towns throughout the state, we found people quietly doing the work of abolitionist organizing and mutual aid—oftentimes in much more challenging political environments than what we had ever experienced. Together, we forced the court to open their commission up to the public. A few short months later, we officially formed the Illinois Network for Pretrial Justice, a statewide coalition to end money bond and reduce pretrial jailing.

At the Supreme Court commission’s public hearings, people from throughout Illinois spoke out in support of ending wealth-based jailing. At every hearing, the only people who spoke in support of the money bond system were prosecutors. In Chicago, Lavette Mayes once again shared her story. Flonard Wrencher and Timothy Williams also bravely told the officials of the harm they had experienced due to unaffordable money bond. Throughout our campaign, it was clear that, more than any legal arguments or stats, it is the stories of everyday people that do the most to change the opinions of people in power.

The commission released its findings and recommendations in April 2020 and validated many of our network’s policy positions. Most importantly, both the network and the Supreme Court commission agreed that no one should be incarcerated simply because they cannot afford to pay a money bond. The commission also agreed that we must limit the number of criminal charges that are eligible for pretrial incarceration, a hallmark of the Pretrial Fairness Act.

A month prior to the report’s release, the network officially launched the campaign to pass the Pretrial Fairness Act and Governor JB Pritzker announced that ending money bond would be a priority for his administration. After years of organizing, we felt we were finally in a position to not just end money bond but win a system that would reduce pretrial jailing in our state.

Our plans came to a grinding halt with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The legislature went home—along with everyone else who could afford to shelter in place—and we were told it was unclear when they would return. But it was clear that public health and the state’s finances were going to take top priority whenever they did.

That summer, though, people power in the streets would once again change the terms of debate and our network was ready to act. Millions of people across the United States protested the police murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and many others. The young Black organizers leading this movement didn’t shift the Overton window so much as they shattered it. Unlike many elected officials who tried to retreat from the Black Lives Matter movement, painting it as too radical, the Illinois Legislative Black Caucus took the opportunity and ran with it. In January 2021 they passed several omnibus bills aimed at addressing systemic racism. At the center of the criminal justice bill, the SAFE-T Act, was the Pretrial Fairness Act.

Over the next two years, network members would work with stakeholders from across Illinois to prepare the state for implementation of this law that wouldn’t just end money bond but actually transform our state’s pretrial system.

Throughout the past two years, right-wing political operatives and law enforcement officials have worked in concert to derail the law from taking effect. Millions of dollars were poured into a misinformation campaign that was meant to scare the public out of supporting the law and get them to vote out the legislators who supported it.

However, a rigorous public awareness campaign was able to limit the impact of misinformation and no legislators lost their seats as a result of attacks on the legislation. Organizers and legislators were also able to successfully pass a trailer bill further clarifying the law to ensure successful implementation while preempting the possibility of significant rollbacks.

An unexpected roadblock would delay implementation, though. In September 2022 prosecutors across the state filed frivolous lawsuits challenging the constitutionality of the law. The case went all the way to the Illinois Supreme Court, and implementation was delayed as the court deliberated. The court’s decision to stall implementation would be justice delayed but not justice denied. Although it took seven months, the court ruled in favor of the Pretrial Fairness Act and put it back on track to be implemented starting September 18, 2023.

Our fight, though, is far from over. Ending money bond was our target; pretrial freedom is our goal. As we learned early on, implementation is a challenge unto itself. We have once again trained up hundreds of court watchers who are currently watching hearings in eight counties. Our policy team will be using that data to support successful implementation and, when necessary, to file lawsuits challenging those who continue to try to undermine the law’s impact. We are also working to stop a statewide expansion of electronic monitoring. With our partners across Illinois, we are working to educate our communities about the dangers of false alternatives to incarceration and are raising the alarm that replacing money bail with electronic monitoring would be a grave injustice.

In just a few short weeks, we’ll also be forced to play defense in our legislature, where opportunists will undoubtedly try and weaponize individual cases to roll back the rights of hundreds of thousands of legally innocent people. As we saw right here in Illinois, fearmongering and misinformation are the main tools used by the opposition to trick the public into opposing pretrial reforms. In New York, for example, this playbook was used to change public opinion and rollback important reforms to the pretrial system.

Throughout our state, Black people have been disproportionately impacted by wealth-based jailing. The Pretrial Fairness Act ensures that millions of dollars that would have been extracted from Black communities will stay in them. As our state reduces pretrial jailing, it is essential that the money once used to jail our most marginalized residents is redirected toward helping those communities heal. Dollars that would have been used to hold people in cages should be redirected toward services such as health care, community-based substance use and mental health treatment, affordable housing, and quality education. It is not enough to simply implement this reform. We must use it as a starting point for beginning the long work of undoing the harm pretrial jailing has caused our state.

The Pretrial Fairness Act took a great amount of power away from police, judges, and prosecutors to hurt our communities—but it did not end the harm. Securing a policy change is one thing, but implementing it is its own fight. Everyday people can change what’s possible, but the carceral state will not simply allow itself to be dismantled without looking for new ways to achieve the same goals.

As we secure successful implementation of the Pretrial Fairness Act, we must be prepared to prevent an expansion of electronic monitoring and other punitive pretrial conditions. It is essential that we not only defend the law but continue to chip away at systemic racism and mass incarceration. We hope our work in Illinois can serve as an example, to show that we can work in the streets and in the legislature to weaken these systems of injustice and create space for a world where our communities have the resources they need to thrive and we can address harm without causing further harm.

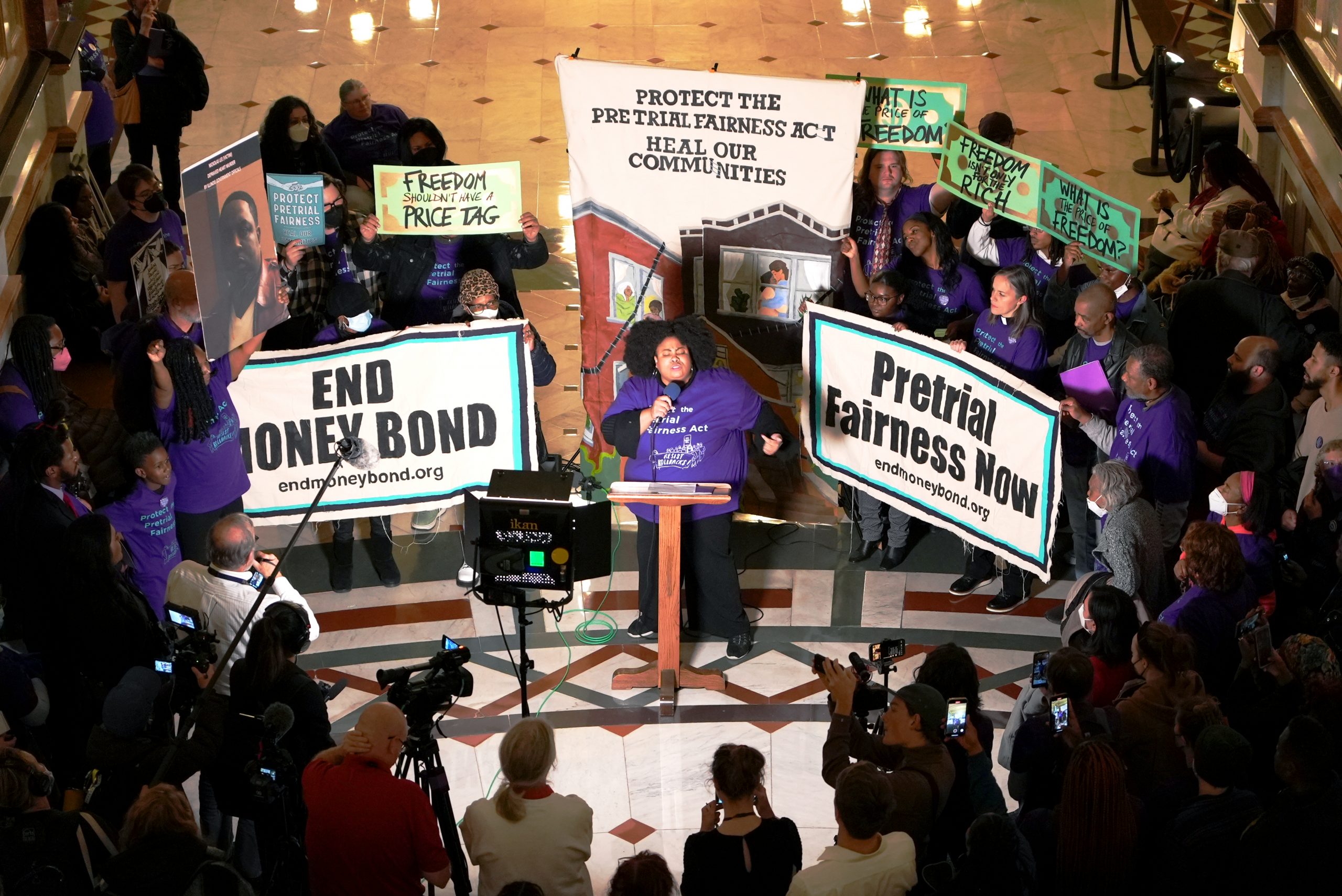

Header image: Members of the Illinois Network for Pretrial Justice march in Springfield, Illinois, to demand pretrial freedom on July 13, 2019. (Image courtesy of the Illinois Network for Pretrial Justice.)