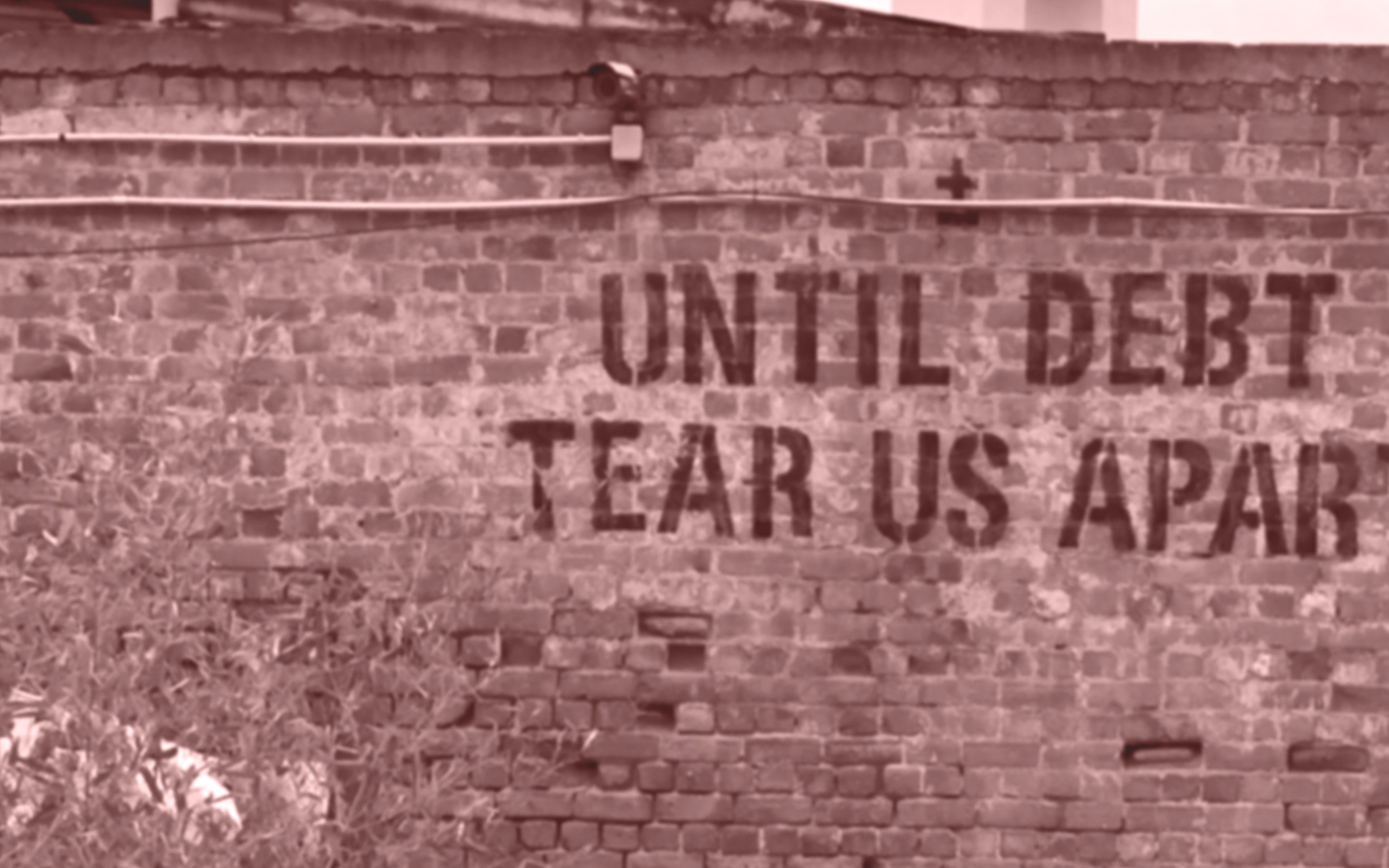

Policing and the prison–industrial complex constitute a particularly visible form of punishment in the United States. Debt is its carceral relative. In her 2010 presidential address to the American Studies Association, Ruth Wilson Gilmore recognized the carceral logics of debt, observing that “debt robs” and that “debt also disciplines.”

Most people in the United States owe debt, with at least three in four households maintaining some kind of debt. The typical household now incurs more in debt each year than it earns in income. Twenty percent of households can’t pay health-care costs and owe an average of $12,430 in medical debt. Over 43 million people collectively carry $1.6 trillion in student loans. And about half maintain an unpaid balance on their credit cards. What’s more, nearly half of people with debt experience harassment by collection agents, and many feel threatened to repay despite routine errors in medical, student loan, and credit card bills.

Debt isolates people from friends and family, exposes vulnerable people to harmful conditions, reproduces racist sexism and other oppressions, restricts people’s movements, and excludes people from opportunities.

Parallel to the ways probation and parole supervision, electronic ankle monitors, and prison cells confine and surveil people by the millions, debt functions as a mechanism of social control—delivering discipline and punishment on a mass scale that keeps people working to pay down what are often considered odious debts. In other words, people are trapped into exploitative debt obligations via carceral logics similar to the ways they are captured into confinement and surveillance.

Decarceral thinkers and doers

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

In this context, a credit score—often required to borrow—plays a unique role in sustaining carceral logics. Many people know their credit score—the three-digit number that purports to predict the likelihood of loan repayment. “Good” credit, such as a Fair Isaac Corporation (FICO) score above 700, can mean getting a better interest rate on a loan and paying less to borrow money. Yet persistent racial disparities in credit scores mean that debt tends to be cheaper for white people and more expensive for Black and brown people. Over half of white people are determined to have good credit compared to 21 percent of Black people.

Credit scoring is rarely politicized in the same ways as other debt-related social problems. For example, most people are aware of social movement activism to cancel student loans or medical debt. We argue that credit scoring deserves the same kind of scrutiny.

In our own work, we have argued that credit scores are incapable of objectively assessing a borrower’s risk. We further argue that claims of credit scores’ objectivity legitimize an exploitative system of evaluation that mediates people’s access to means of survival. Credit scoring thus conscripts people into debt and expands the scope and scale of discipline and punishment. This, in turn, invariably expands the potential for criminalization and incarceration.

Before we unpack our research and its implications for anti-carceral policy and advocacy, it’s useful to step back and look at how we got here in the first place. Examining the history of debt as a proxy for criminalization and incarceration—and the role of credit scoring in the legitimation of debt—can help us think critically about strategies for correcting the omission of credit scoring from the larger conversation about the carceral attributes of debt and other kinds of economic exploitation.

In the earliest days of borrowing and trade, credit existed in the form of community- and relationship-based arrangements. Merchants and traders made economic decisions to lend and borrow based on individual evaluations of character and trust. In a society where both slavery and indentured servitude were legal and common, such arrangements were exclusionary and class-based: only some—those who held the appropriate racial and class markers—had access to these early forms of credit.

Tracking and assigning value to people’s worthiness, like the practice of credit scoring, has its roots in our nation’s enduring economic system of racial capitalism, which has promoted slavery and other violence against Black people, Indigenous people, and people from other nations. As we have written elsewhere, racial capitalism clarifies that “the development of capitalism has always gone hand in hand with the social construction of race.” According to political philosopher Cedric Robinson, the emergence of capitalism was not a rejection of a feudal order where a poor underclass of people were liberated from servitude to nobles and landowners. Rather, capitalism replaced a feudal hierarchy with a racial hierarchy, which justified disproportionate violence toward certain groups of people based on their racial and ethnic backgrounds. This system of racial capitalism has maintained an unequal distribution of resources since its emergence as a prevailing economic system. Thus, capitalism as we know it has always been, and will always be, based on and justified by racialized logics. There is no capitalism without racial capitalism.

The oppression of poor and racially marginalized people in the United States has always been critical for the continued functioning of our economic system. Therefore, these underclasses have consistently been tracked and monitored more closely than other groups. With respect to slavery in particular, sociologist Simone Browne has theorized the concept of dark sousveillance, explaining how “surveillance technologies installed during slavery to monitor and track Blackness as property . . . anticipate the contemporary surveillance of racialized subjects.” The contemporary practice of credit scoring—where an individual receives a numeric, hierarchically arranged score imbued with economic value—can be likened to the many ways society surveils, punishes, and extracts wealth from people, especially Black people.

Evidence of the connections between punishment and debt abounds. After the abolition of slavery, debtors’ prisons incarcerated poor people for stealing food to survive and for failing to pay outstanding debts. Combined with Black codes and vagrancy laws enacted by white political regimes, Black people were routinely forced into debt bondage, enabling convict leasing and other slavery-like conditions that provided free labor to business and property owners. Steel and coal companies in southern states, for instance, grew their empires in the early 1900s by relying on prison labor of predominantly Black men to carry out the dangerous work of digging thousands of pounds of coal per day and stoking blisteringly hot fires in coke ovens.

The birth of credit bureaus in the mid-nineteenth century introduced what historian Josh Lauer calls “a new surveillance institution that would bring thousands of Americans into an expansive network of social monitoring.” Early credit reports included information on borrowers’ appearance, personality, drinking habits, and race and ethnicity. Businesses and ruling-class lenders used this information to their advantage, explicitly discriminating against poor white and Black borrowers in ways that guaranteed a stable hierarchy based on race and class. Early credit reports also included a potential borrower’s gender, enabling lenders to refuse loans along systematically sexist lines. These exclusionary practices persisted throughout the twentieth century and were not made explicitly illegal until 1974 (discrimination based on sex assigned at birth) and 1976 (discrimination based on race and ethnicity). After the passage of these regulatory policies, credit bureaus increasingly relied on new, purportedly more sophisticated statistical techniques that, despite promises to the contrary, further enabled a racial capitalist system to subjugate Black people by undermining their wealth accumulation and preventing their equal participation in the economy.

Today, credit scores are used in decisions over ever-widening aspects of everyday life, part of a phenomenon that sociologist Tamara Nopper calls “the datafication of social life.” Among other things, credit scores or their underlying data are used to decide whether a person can get a job, purchase car insurance, or rent an apartment. As Nopper’s research shows, social media activity may influence credit scores despite the fact that many people don’t agree to have their social media activity data included in credit reports. Even dating apps are experimenting with using credit scores to help people find acceptable matches. In all cases, higher scores pave the way for desired and socially accepted outcomes.

Today, Experian, Equifax, and TransUnion are the credit bureaus that collect data on individuals’ financial accounts and payment histories for generating consumer credit ratings. Credit bureaus—themselves for-profit corporations—then sell this information to lenders and others for a fee. There are many different types of credit scores, each used for a different purpose. One of the most well-known is the FICO credit score, which is readily available through financial institutions such as banks and credit card companies, often accompanied by a visual, color-coded gauge signaling a person’s creditworthiness.

We tend to accept credit scores as necessary and inevitable for keeping our lives in order. Yet credit scores are relatively new inventions: Three-digit scores such as the FICO credit score weren’t popularized until the late 1980s. Thus, credit scores have become widespread in less than one generation. In that short time, credit score usage has broadened from decisions related to borrowing and lending to decisions related to hiring and housing without much scrutiny or oversight.

For many, however, the ubiquity of credit scores rightfully raises concerns about their role as a mechanism of social control. It is increasingly common for a credit score to mean the difference between securing a place to sleep and remaining unhoused, with a low score effectively closing the door to a roof over one’s head. Credit scores populate spreadsheets with rows sorted to easily identify people deemed risky and untrustworthy—disproportionately people who are poor and oppressed. Lenders exploit these hierarchically arranged scores to extract the most money from people who can least afford it.

This outsize power over everyday life is consequential for everyone, and especially for those disproportionately targeted for criminalization and incarceration. Criminal punishment systems have relied on similar prediction models as rubrics for developing their own recidivism and sentencing guidelines, among other uses. Touted as far preferable to human decision-making, algorithmic scoring provides those in power with a mechanism for assessing risk and mitigating their own liability. In this way, lending institutions, property management companies, and criminal punishment systems hide behind these assessments to ensure people being scored bear the burdens of risks and liabilities while the scorers retain any benefits for themselves.

Given the pervasiveness of credit scores in everyday life and the rise of risk assessment instruments in criminal systems, our research team set out to study credit scoring’s unique role in sustaining carceral logics. First, we conducted a review of academic literature on credit scoring published between 1971 and 2021. Then, we developed and tested a theory of credit scoring as a carceral practice. Studying the literature this way matters because policymakers routinely rely on the assumption that credit scores are objective and provide an unbiased version of the information necessary for a government-backed borrowing and lending system.

Contrary to the assumption about objectivity and unbiasedness, our research found that credit scoring relies on problematic assumptions about deservedness based on particular ideological perspectives on economic markets, risk, and surveillance. The literature shows that justifications for credit scoring rely heavily on neoclassical economics, which uncritically assumes the benefits of competition or the so-called “freedom of markets.” As legal scholar Mehrsa Baradaran explains, political elites have leveraged the “freedom of markets” philosophy for developing laws and regulations that plunder wealth from poor and oppressed communities. The reliance on neoclassical economics contradicts claims by economists, lenders, and policymakers that credit scoring is a neutral way of assessing a borrower’s risk. Such claims are more closely ideologically aligned with white supremacist belief systems that rely on myths of free markets and facts divorced from history and human experience. In reality, there is nothing neutral or objective when it comes to data and information.

More surprising, our review of the literature found that credit scoring has consistently failed to predict the likelihood that a borrower will repay a loan. Instead, we traced how this literature has helped justify the use of credit scoring by arguing that it successfully enables lenders to mitigate risk that comes from Black and poor white people’s assumed bad decision-making and poor character. What’s more, most studies fail entirely to control for race and ethnicity when seeking to determine whether credit scores actually help to predict risk. As sociologist Davon Norris observes, by failing to consider race directly in their models, scores can “rise or fall as people behave in ways that scoring systems reward or penalize, while the broader institutional and regulatory determinants of scores are obscured.” Norris calls this “an epistemology of ignorance,” where scoring models rely on systematically racist and biased data such as a borrower’s income or zip code that provide a facade of fairness and objectivity.

Completely ignoring the possibility that race (read: racism) might predict credit scores undermines the question of whether credit scores might predict risk. Banks can justify denying loans to Black customers—something that banks do a lot—based on low scores rather than their racist assumptions about borrowers’ bad decision-making and poor character. Credit scores can’t provide an alibi for racism and predict risk at the same time. This feigned ignorance exemplifies how the current practice of credit scoring—and the justifications for its continued presence in everyday decisions—functions as a technology of social control and as a carceral practice that disproportionately impacts oppressed people.

Black and other oppressed peoples in the United States have been subjected to technologies of social control throughout this nation’s history. As our recent article summarizes: In the afterlife of slavery, credit scoring became a technology for anti-Black surveillance and punishment. When banks and lenders use credit reports or scores to determine how much interest a person is charged for a loan, that measure is being used to punish as much as it is used to reward. Scoring is also used to determine access to housing and sometimes even job attainment. Though these uses of credit scores may sound unreasonable, they are actually aligned with how credit scoring has always been used: to shape people’s access to means of survival.

Since their invention, credit scores have served as a proxy for who is a good consumer who deserves the opportunity to build wealth—for example, with a mortgage or small business loan. As our research shows, the credit score has been a subjective measure based on moralized assumptions about people’s character since its inception. Credit scores have always been formulated on racist and classist assumptions about Black and poor white people’s inherent trustworthiness. Under the guise of an objective measure of risk, today’s scores merely reflect our society’s assumptions about which groups of people are generally good and deserving and which must be subjected to practices that hold them down—economic, carceral, and otherwise.

Ultimately, our work has led us to conclude that the historical genesis of credit information and credit scoring forecloses the possibility of reform. Attempts to ameliorate the racist impacts of credit scores have resulted in further surveillance and social control of the most oppressed populations, while propping up those who are already well off. Only the abolition of credit scoring might create a new template for imagining alternatives for economic security and well-being. Yet, to be effective, any alternatives must be linked to broader anti-capitalist projects. Liberation from oppression will not be realized once everyone has access to an affordable mortgage or passive income streams. This is because debt is fundamental to our economic system of racial capitalism.

When Gilmore addressed the American Studies Association, she urged all of us to consider the broader project of imagining abolitionist futures: “No matter what we study, scholars are all about the future, about saying something tomorrow or the day after that.” We do not yet know what might follow from the abolition of credit scoring, but we’re encouraged to consider the future and ask: “What sorts of futures can we imagine and begin to make real in the present—today, tomorrow, and the day after that?”

Image: Daniel Thiele/Unsplash/Inquest