In New York’s northernmost reaches, a remote region of the state often called “the North Country,” the county jails had many critics and few admirers throughout the 1920s. Each new report from the Prison Association of New York lodged the same complaints about local jails’ “glaring deficiencies and abuses”: Jails were dangerously overcrowded (a surprising predicament for the decidedly uncrowded expanses just beneath the Canadian border), they were crumbling structural relics, and they were marred by episodes of bribery and corruption. North Country jails held—at least in theory—local people accused of low-level infractions who did not generate a great deal of public sympathy. Even the Empire State’s most avid reformers mustered little energy for campaigns of improvement, with one criminologist derisively describing the typical jail population as “bums, booze-fighters, [and] suspicious characters.”

Yet, when the prison commissioners entered Northern New York jails for annual inspections, they heard varying accents and foreign languages ringing across the halls. Alongside the usual local suspects, inspectors encountered migrants awaiting hearings and deportations—the result of deals inked between counties and the federal immigration service over the previous twenty years. Some of the people detained were Chinese laborers, ineligible for entry under the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. Following long voyages across the Pacific, Chinese migrants had used Canada as an entry point to the United States, often filing habeas corpus appeals demanding their freedom from New York lockups. Other cells held Canadians, for whom crossing the border for work and pleasure was a regular part of life. Now they found themselves “rotting in American jails,” an alarmed British newspaper opined. Canadians and Chinese shared the space with Italians and Jews attempting to evade new quota laws that had made legal migration an imposing, if not impossible, task. When Congress passed the 1929 Undesirable Aliens Act, criminalizing unauthorized entry into the United States, it trapped even more migrants in the jam-packed jails stationed along the southern and northern borders. These jails were sites of coercion and neglect—dozens of detained migrants died in Northern New York’s dangerously overcrowded facilities while waiting for backlogged immigration hearings—but they were also sites where migrants lodged legal claims, plotted escapes, organized with aid groups, and fought for the right to stay in the United States.

Migrants’ presence created a predicament for Northern New York officials: On the one hand, jails filled with protesting people from around the globe were a liability. They brought bad press and bureaucratic headaches. On the other hand, migrants brought money. Each detained migrant represented a paycheck from the federal government to the local government, compensation for each night the immigration service “boarded” a person in the county jail. These paychecks had padded county budgets since the turn of the twentieth century and had made these small, peripheral towns integral to the federal work of deportation. While federal stations such as Ellis Island became the quintessential image of immigrant processing in the early twentieth century, it was at county jails that the U.S. government stretched its discretionary authority, held migrants for the longest durations, and forged enduring relationships between federal bureaucracy and local communities.

Nearly a century later, in the spring of 2019, towns in Louisiana would weigh many of the same concerns when considering how imprisoned migrants might keep county budgets in the black. Parishes throughout Louisiana had undertaken costly jail expansion projects in the prison-building booms of the 1980s and 1990s. Jackson Parish, for example, had room to hold 1,260 people in its jail, roughly 1 in 13 of the parish’s residents. In 2017 bipartisan criminal justice reform efforts in the Louisiana State Legislature successfully reduced sentences and lowered the number of people jailed in the state. With jail populations declining, local officials worried about how they would pay back construction bonds and retain corrections jobs. Many communities found an answer and an enthusiastic partner in Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), signing contracts to incarcerate thousands of migrants in parish jails in exchange for about $70 per detained person per night. Parish jails housed migrants from Cuba, Haiti, Venezuela, India, Togo, and beyond. Many were asylum seekers, fleeing political violence and persecution, who had crossed the southern border before being sent to remote corners of Louisiana to await adjudication. They included men such as Walter Corrales, who was detained in a room with sixty other migrants in a Concordia Parish jail. Corrales had feared for his survival under the authoritarian Honduran government. Still, he called his time in Louisiana jails the worst days of his life. Meanwhile Sheriff Cranford Jordan of Winn Parish declared migrants like Corrales a “blessing.” Their incarceration was keeping his jail open and his parish financially afloat.

Despite decades of precedent for detaining migrants in local carceral facilities, even careful observers were caught off guard by what was occurring in Louisiana’s jails. One attorney from the Southern Poverty Law Center said that while advocates knew criminal justice reform might lead rural jails to close and turn into immigration detention centers, they did not anticipate that jails would incarcerate both administratively detained migrants and those accused of criminal offenses in a shared space. Immigration detention in county jails, confessed a Louisiana law professor, “simply wasn’t on anyone’s radar.” In fact, county jails have been foundational to the project of federal immigration law enforcement for over a century—but they have operated with a staggering absence of oversight or public awareness.

The plenary power doctrine, crystallized by the courts at the turn of the twentieth century, dictates that the executive and legislative branches are responsible for immigration policy decisions and that courts should rarely, if ever, entertain challenges to decisions about admission or expulsion. Plenary power, a term similarly invoked in Indian affairs and in cases involving the political status of U.S. territories, indicates complete and absolute authority. The power over immigration was affirmed in the 1889 case of Chae Chan Ping v. United States, in which the Supreme Court ruled that the government could exclude a noncitizen on whatever grounds it deemed necessary. Individual constitutional rights became secondary; Congress held the power to discriminate against arriving migrants on the basis of race, gender, political affiliation, or any other category it deemed relevant.

Plenary power also bore a corollary notion: that federal authority over immigration was indivisible, and that states and counties had no independent role in developing or administering immigration law. This doctrine upended the nineteenth-century U.S. immigration regime, where state and local officials created and enforced immigration laws. Yet, though the courts dictated that localities could not produce or execute immigration policy, there was ambiguity about how the federal government might delegate power to them. Local actors did not control the core aspects of immigration—decisions about the admission and removal of noncitizens—yet they held significant power in shaping the enforcement of immigration law. The vast, virtually unchecked plenary power of Congress and the president to create immigration policy gave rise to a bureaucracy that operated with stunning autonomy: It was insulated from judicial intervention; it resisted oversight and administrative norms at every juncture; and it used subcontracting, transfers, and intergovernmental agreements to further distance itself from accountability.

Incarcerated or detained noncitizens “sit at the intersection of two powerful lines of deference,” writes legal scholar Emma Kaufman. In cases involving the immigration status of foreign nationals, courts have historically deferred to the political branches, which have near-complete sovereign authority over entry and exclusion. In cases involving prisons and jails, courts have routinely deferred to policies curbing the constitutional rights of incarcerated people. The 1980s saw a judicial retreat from liberal rulings for incarcerated peoples’ rights in favor of arguments that stressed the peculiarity of carceral institutions and recognized the broad power of prison officials to restrict rights in the name of “legitimate penological interests.” Together, these two lines of deference have vested extraordinary power in sheriffs and other jail workers tasked with policing the day-to-day lives of people with few rights and only the narrowest paths to judicial recourse.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

Still, few groups influenced the trajectory of detention more than migrants themselves. Through individual and collective resistance, they have challenged both the state’s power to detain and the relationship between the federal government and localities. One way migrants have attempted to secure their freedom and undercut the legitimacy of detention has been through the courts: both routine, individual petitions—requesting habeas corpus or reprieve through bail—and more complex legal challenges to jail conditions and the immigration agency’s power to incarcerate. Against imposing odds, they have returned to court repeatedly, often securing victories on procedural grounds. Even when they have not won, their legal cases have brought detention into public consciousness and created a record of abuses of power.

Migrants’ protests and critiques of state power have led officials to think of the jail as a tool to thwart resistance. Transferring migrants between jails has been one way to separate them from the solidarity they’ve found in one another. As a result, the material evidence of migrants’ lived experiences is easy to overlook, scattered as it is among the records of bureaucrats and lawyers. Nevertheless, a study of such institutional archives offers ways to witness how migrants have pushed back against the capriciousness of jailing and removal.

The artifacts in these archives take many forms: a butter knife carved into a key by an Italian attempting to break out of a detention cell, letters from Chinese migrants offering to expose their smugglers’ secrets in exchange for freedom, political speeches drawing parallels between Jim Crow and migrant incarceration, funeral programs for an asylum seeker who died in detention and another for a migrant child who drowned in a Coast Guard apprehension at sea. There are thousands of affidavits from detained people, testimonies that attempt to make experiences of persecution legible to the legal apparatus of the United States.

These sources are complemented by migrants’ letters and petitions, which excoriate the contradictions between professed U.S. ideals and the conditions they have encountered, including incarceration imposed without trial. “Do you Americans like when people suffer? Does God give Americans power to do evil things?” wrote a Haitian migrant interdicted at sea in a letter contained in the rare books and manuscripts collection of Duke University. In another letter in the same collection, a Cuban in Louisiana described his incarceration as a form of state-sponsored disappearance: “[Since] Oct. 2, 1995, I have been kidnapped by the [immigration] service in parish jails.” Yet another letter by asylum seekers held in Florida framed U.S. actions as the latest in a long list of hypocrisies: “The U.S. is going to China, Cuba, and several other countries telling them about civil rights violations. The Indians were run off their land by the U.S., put on the reservation. Now [the immigration service] has [migrants] hiding here in the Manatee County Jail.”

The United States currently has 2,850 county jails, most of which have existed in some form for more than a century. To make any generalizations about these disparate spaces is treacherous business. Detention was and is a process taking place across the nation, though certain localities have seen migrant jailing moved from a local issue to a point of national reckoning. Often this occurred in unexpected places: Malone, New York, and Galveston, Texas, in the beginning of the twentieth century and Immokalee, Florida, York, Pennsylvania, and Avoyelles Parish, Louisiana, at the end. These communities differ in virtually every way, from demographics to geography, politics to population—yet each of them chose to work closely with the immigration service to expel the people the nation had deemed dangerous, undesirable, or otherwise “illegal.”

In 2023 ICE detained an average of 28,289 migrants per night, down from a pre-COVID peak of 49,403 migrants per night in 2019. Even this reduced number is roughly twelve times as many people as the agency detained fifty years ago. Detention is the backbone of the U.S. border enforcement regime, relying not just on private prison companies and federal detention centers but on the hundreds of city and county jails that contract with the immigration service. The cruelties and injustices are manifold. But they are not new.

“Here, almost daily, Federal officers call for aliens,” a local writer observed in upstate New York in 1927. “They are handcuffed. They are led through the main streets of this village to be photographed. Yet [the] spotlight that plays around Ellis Island is not trained upon small county jails.”

It has been nearly a hundred years since that journalist encountered migrants from Asia, Europe, and Latin America detained, out of sight and out of mind, in the rural jails along the Canadian border. Today, debates over federalism have come to the forefront in fights about sanctuary cities, migrant busing, and how local law enforcement works (or refuses to work) with ICE. The questions raised by these fights are the same ones that migrants and their advocates confronted, shivering in a converted barn against the New York winter. Who is responsible for detaining migrants? What is the relationship between a seemingly unaccountable federal immigration enforcement bureaucracy and a local municipality? Does a locality have to cooperate when the federal immigration service requests, or in some cases, demands, its assistance?

And most importantly: How can a self-proclaimed nation of immigrants also be a place that imprisons tens of thousands of immigrants, exiles, and refugees?

Excerpted from The Migrant’s Jail by Brianna Nofil. Copyright © 2024 by Brianna Nofil. Reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.

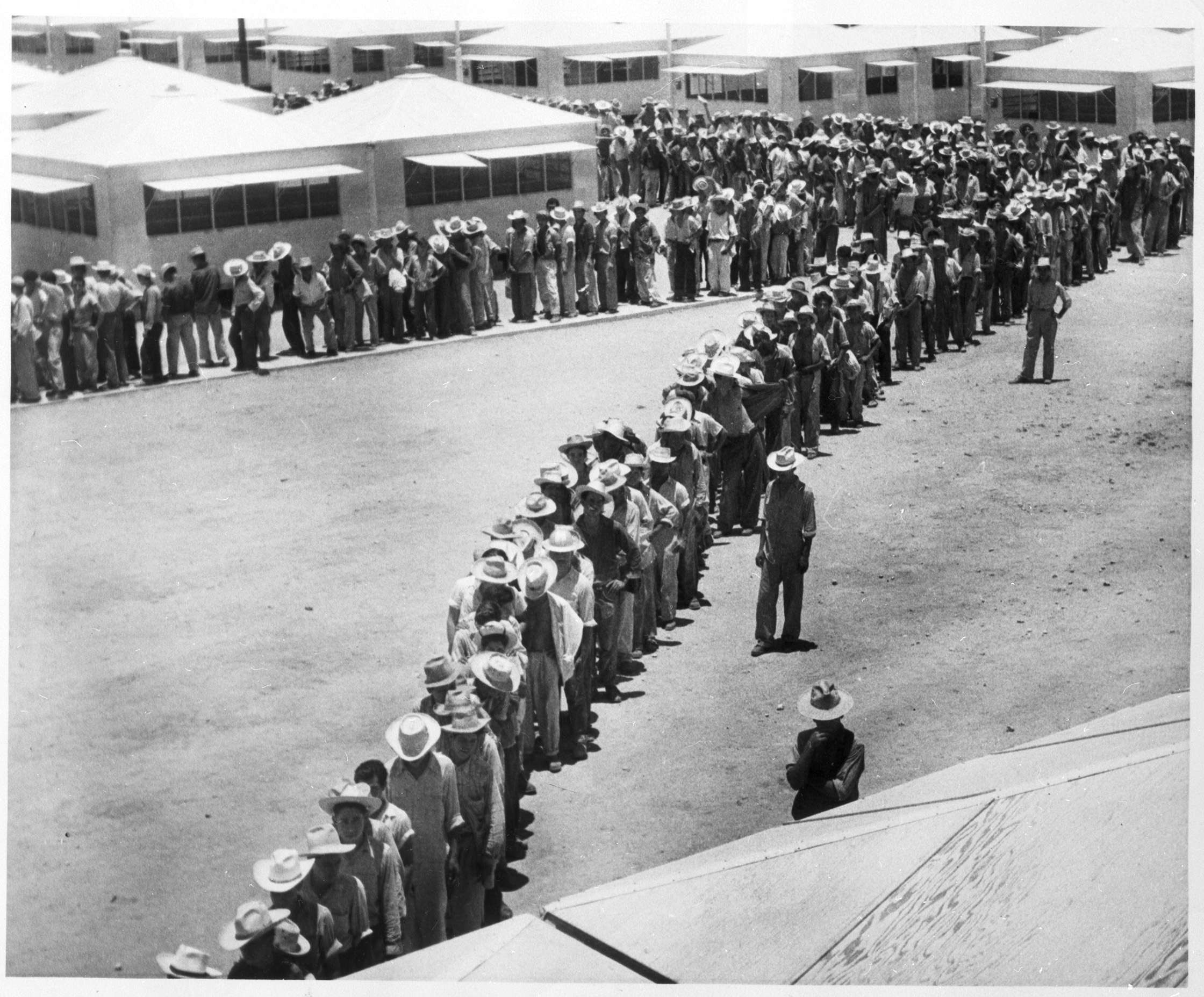

Image: Texas AFL-CIO Mexican American Affairs Committee Records/University of Texas at Arlington Libraries