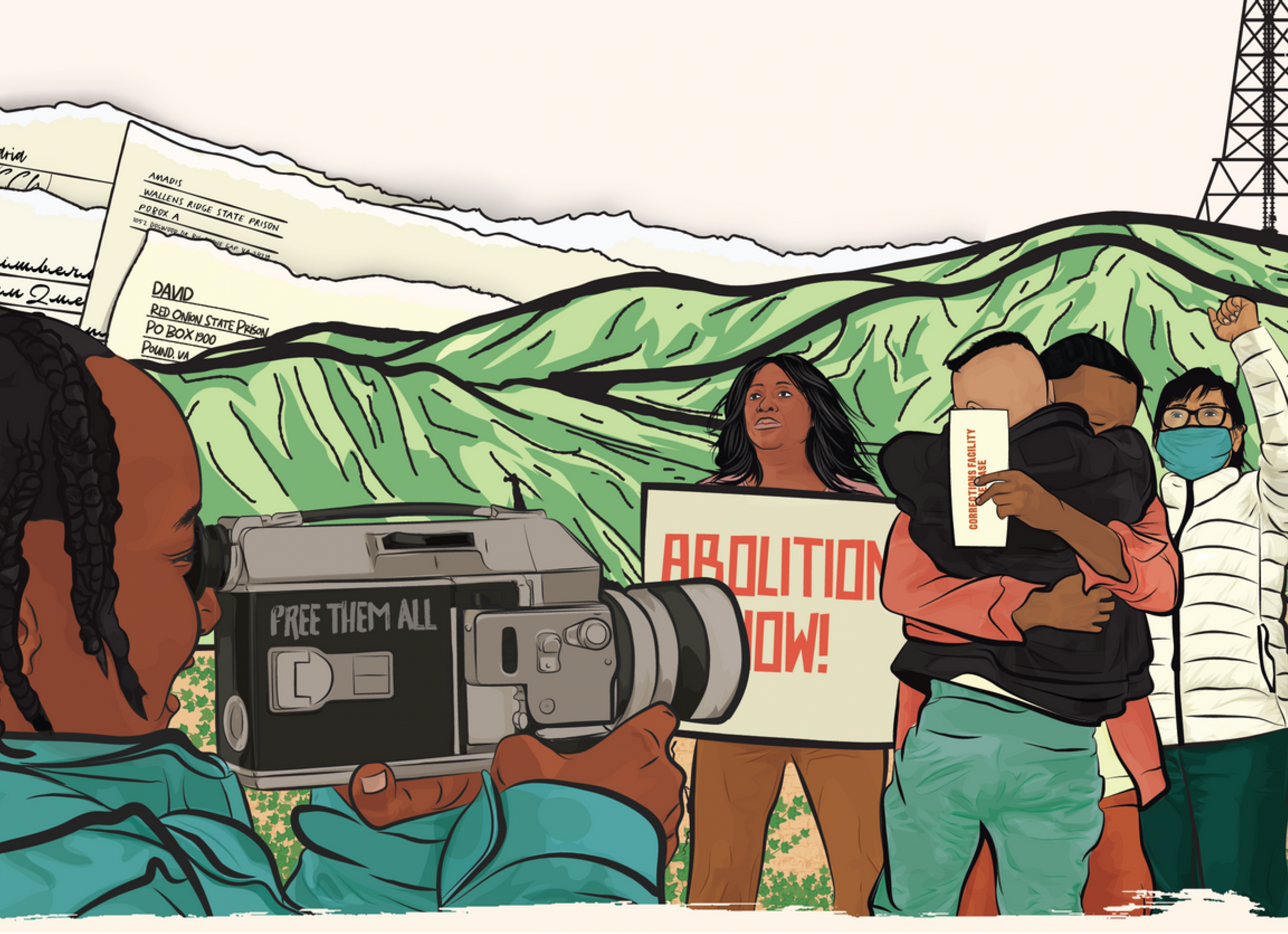

In October, Inquest hosted a public screening of Beyond Walls, an anthology of five short documentary films advocating for police and prison abolition. Beyond Walls grew out of a project by Working Films, a mission-driven nonprofit that seeks to resource grassroots social movements with documentary films. To date, Working Films has partnered with local organizations to host over fifty screenings nationwide. When communities organize screenings of the anthology, the films are offered alongside a dossier of concrete tools and discussion guides to help shape action toward creating a world without police and prisons. The anthology itself was curated by the Center for Political Education, Critical Resistance, MPD150, and Survived + Punished.

The screening was followed by a panel discussion with Working Films’ director of campaigns and strategy Andy Myers, and two of the directors whose work is included in Beyond Walls: scholar-activist-filmmaker Sylvia Ryerson, and formerly incarcerated filmmaker Adamu Chan. The discussion was moderated by Inquest coeditor-in-chief Andrew Crespo. The transcript below was edited for length and clarity.

Andrew Manuel Crespo: Part of the power of these films is the emotion that they create. There’s a kind of weight that comes from how the filmmakers are able to create a sense of a connection, across space and time, that brings the reality of living with incarceration into the room.

Andy, I’d like to start with having you introduce this project. Tell us what this compilation is, how this came together, how these filmmakers came together, what the goals of the project are—and how that connects to the mission of how Working Films aims to use media to motivate change in the world.

This dialogue is from the collection

Decarceral Filmmaking

Essays spotlighting films and documentaries that have something to say about our crisis of mass incarceration.

Andy Myers: This compilation came from a program we have called Docs in Action, which exists to provide movements with new short films they can use in their work. A lot of foundations, when they fund films, their staff just decides which films should be funded, even if they know nothing about the issue, and even if they’re not directly impacted. What we tried to do was place the decision-making power in the hands of people who are directly impacted and the people who have been doing this work for the long haul. So when we decided to focus on abolition, we partnered with organizations that have been doing prison–industrial complex abolition work for a very long time, and they told us, these are the stories we want.

A lot of our goals at the time were really to try to define terms like “defund the police.” We wanted to show some of the negative impacts of the prison–industrial complex on individuals, but also their families and broader communities. We wanted to show examples of resistance to the PIC with concrete stories that we could see on screen. We wanted to show what an alternative society could look like. What would it look like if we stopped spending all of our money and resources and attention on prisons and police and started investing in communities? Our partner organizations came up with those messaging goals, and then decided which films we’d been sent were most in line with those values.

And now we’ve built this resource, and we’re getting the word out to communities that if they feel they can use it, please do. We have a budget to pay for venues and honoraria for panelists. And however they want to use the anthology, they can. If people want to use the screening to train audience members on court watching, do that. If they want to do a film screening that shows the connections between immigrant justice and the PIC, do that.

We see these film screening events as an opportunity for people to learn a fuller story of what happens when you call the police, and then give people concrete tools for what they can do instead. For example, I’m based in North Carolina, and across the state we’ve been doing screenings that get people to go to de-escalation trainings afterward. It’s a real concrete opportunity to get involved. We’ve also done a number of screenings with Black and Pink, in which after the screening, they host an hour-long workshop on their PenPal Program to connect audience members with folks who are incarcerated so they can start those relationships and build solidarity. We’ve also worked with a lot of environmental justice organizers who are using the screenings to show how the prison–industrial complex is connected to environmental racism. No two screening events look the same, and each one is designed to platform the local organizing that’s happening.

AMC: Adamu, I have so many questions about your film—it’s beautiful as a piece of art. It’s an incredibly intimate film. I think viewers almost feel like we know you after we’ve watched it. But, of course, we don’t know your whole story. When did you become a filmmaker? Was it before you were incarcerated? Related to that, I’d love to hear more about the Media Center at San Quentin where you started making the film while incarcerated, and the role that it played in the journey of your development as a filmmaker and an artist.

Adamu Chan: I had no background in filmmaking before 2018. So this is a very recent thing, and I’m still amazed that I was able to do this. Almost killed me, but I’m here.

San Quentin is a very old prison. It’s one of the most notorious prisons in the country. It’s one of the only prisons in California that’s really proximate to a metropolitan area. It makes it accessible for lawmakers and other people to go into the prison. They have tours every day. People come through the prison, they see the prison. What the Department of Corrections does is it takes this story of San Quentin that is in everyone’s consciousness—about it being so terrible, so old, with architecture that looks like prisons that we’ve seen in movies and TV—and says, Look at what we’re doing now. The architecture and the symbols that you see are this reflection of our terrible, carceral past. But look at all these programs that we have for people inside now. We have a newspaper. We have this video program. We have these podcasts. There’s a university inside. In that way, it strengthens the system. It’s kind of a con game.

We who are inside also understood that—that when we were doing these videos from inside, we’re also strengthening the system in certain ways, working for the system. But, a big part of what we were trying to do was using that to also subvert the narrative of carceral progressivism. Having this opportunity inside of a prison fueled me and my colleagues to want to build and grow something out of it. Understanding our privilege within the prison, that meant that we also had a responsibility and a commitment to the rest of the folks across that prison, across the state, across the nation, across the world, who don’t have this voice from inside, who don’t have those tools.

The most important work I was a part of was producing a television show inside that was going out to all thirty-six prisons in California. We were giving people inside San Quentin a platform to tell their own stories authentically with media makers—ourselves—who cared about them, who understood them. It was powerful for everyone across the state to see something that was produced by us. And the impacts of that, I still feel today. When I’m in the Bay Area, people come up to me and they’re like, “Hey, I was in Folsom, I was in Chino, and I saw your show. And it had a huge impact on me.” When I was in San Quentin, people used to come up to me in the yard who had come from other prisons, and they were like, “This had a huge impact on me.” Part of the work that I’m trying to do out here is to also create a film that is for us, centering our folks as an audience, and not having this film that is just this piece of educational material but actually a resource for people to feel solidarity and to commune with each other.

AMC: My next question comes directly from that. I was struck that there are elements of happiness in your film, where we see people experiencing moments of real joy. Yours is the only film in the series that is filmed inside of prison and that shows us, directly, life on the inside. And the story that you’re telling conveys this rich picture of that life, which clearly has sadness in it, but when you think of the emotional register of the films in the anthology, yours is in some ways the most joyful, and aesthetically is also very beautiful in terms of how it is shot. I wanted to ask you about that choice, given what you said. What are you trying to convey there? How does that fit into the story you’re trying to tell about this rich picture of life?

AC: I remember when I first got to San Quentin, before I entered the video program, there was another filmmaker there who later became my friend who made a short video about all of the beautiful places in San Quentin. His narration talks about how there are these small things inside of the prison that are beautiful and that, if you take a minute to stop and reflect on them, it can lift the spirit. That really had a huge impact on me.

As filmmakers, we can show different parts of the human experience. For people who are living under the most terrible circumstances, there has to be beauty, there has to be love and connection. Otherwise, we’re just going to die. And those things exist simultaneously while all of this violence is also happening. Traditional media and art about prisons is very bleak and very sad. I wanted something to be a counter to that. It’s not that it isn’t true, but there is another side of it and that is something that I experienced for myself.

I think the context of COVID-19 is also important to this, too. Everyone across the world experienced isolation in a certain way. It really impacted people, really fucked people up. For myself, the greatest violence of prison is the isolation, being separated from your family and from society. But also within that is this forced togetherness of prison that we don’t experience out here. There’s so many different types of people inside prison, and you’re forced to be together and support each other. People were taking care of each other during COVID-19, sustaining each other and loving each other through what is, in a lot of ways, the worst time in people’s lives.

AMC: The community and the love come through in the relationships that you see in the film. But also there’s a moment, when you hear you are going to be getting out, where you’re experiencing joy—but then your narration also says that you experienced immediate sadness. The immediate sadness of being released. There’s a complexity in that presentation that I think is really powerful. It’s brave, in an abolitionist anthology, to have a piece that is engaging with everything you were just saying. And to your point, it’s just incredibly and importantly humanizing to acknowledge the possibility of joy at the same time that this whole system shouldn’t exist and is awful. To be able to say both of those things.

Sylvia, can I turn you? I would love for you to talk a bit about how you think of this as a project. There’s a multidimensionality to your engagement with this project. You’re not really in the film, but the film is woven through so many different parts of your life. I’d love for you to share a bit of your biographical connection to it.

Sylvia Ryerson: I was lucky enough to wind up at Appalshop straight out of college. It’s an incredible multimedia arts organization based in Letcher County, Kentucky, that is deeply rooted in the social justice movement landscape in Appalachia. Appalshop has always positioned itself as documenting and amplifying these movements, and so when new prisons were constructed nearby in the 1990s volunteer DJs at Appalshops’ community radio station, WMMT-FM, started getting calls and music requests from people incarcerated within listening range of the station. To the radio station’s credit, they opened their airwaves and realized that this ongoing show was a service they could provide, and I think that is because of Appalshop’s movement history. This opening eventually led to the weekly radio program Calls from Home, which I cohosted for many years, and is the subject of my film.

A lot of my interdisciplinary approach to the issue is a product of Appalshop being this very multidisciplinary institution. When I was there, I was a reporter and I was seeing, in the local newspaper, week after week, how plans were being announced for the planned—now continually pending—construction of a federal prison in Letcher County. A lot of the inspiration for all these different projects is how we confront the narrative that’s being pushed to rural communities about prisons as being so-called economic development and even a kind of salvation for the future. That narrative is so deeply pushed on these communities and has been a central part of the geography of the prison–industrial complex across this country. The narrative of prisons providing jobs is essential to that, even though we know, and many studies have shown, that rural prison building does not actually provide the economic development that is promised. When I was first a reporter in Eastern Kentucky, I was looking at other Eastern Kentucky communities that had prisons sited in them and realizing that these rural communities are being lied to about the supposed benefits of hosting a prison.

The reality of building a rural prison means that people will be sent to serve time in that prison from very, very far away and those voices and families and realities are just completely absent from any of the local discourse. My work right now is being a part of the coalition with the Institute to End Mass Incarceration, which is fighting this pending prison proposal in Letcher County. If the prison were built, it would be the most expensive federal prison ever constructed in U.S. history, in a county that was hit by catastrophic floods a couple summers ago and has a severe housing crisis. It’s being debated in the current House appropriations bill. I’m working with people like Andrew, with the coalition, and trying to use this film to share a different side of the story. My research is all about trying to change the dominant narrative we’re told about what a prison is and what it means to have one in your community.

AMC: For the people inside of these federal prisons, it does amount to a near-exile of being incarcerated hundreds of miles away from their communities. It comes through in the mothers in the film saying they’re going to see their sons for the first time in a decade, and only because they’re finally able to organize a shared commute. For federal prisons like the one that we’re working to fight, a lot of them come from faraway cities, and 60 percent of folks in federal prisons are Black and brown. In our minds, when we think of D.C. and Baltimore, and then we think of Central Appalachia, we think of them as very different communities, but these prisons merge them in surprising ways. Sylvia, you know the women who traveled from D.C. in the rideshare, and you’ve lived in Letcher County. How do you think about these two communities in relation to each other? What would it take for them to actually know each other more, given how intimately connected they are and yet so far apart?

SR: I think that politically, we know how and why the prison–industrial complex, being a multifaceted system operating at different scales and in different geographies, is putting these communities into a relationship. It’s a very antagonistic relationship, framed entirely around the premise that some communities can be brought out of poverty through a system that requires the ongoing impoverishment of other communities. That is the political reality we’re operating in. Part of what I wanted to show in the film is the necessity of forging different kinds of relationships between these communities. These are ways that we are able to meet each other in a system that is doing everything it can to make that impossible. Had there not been the radio station, I wouldn’t have gotten to know Michelle, Jeanette, Lessie, and all of the women in the film. I got to know them over the airwaves.

AMC: Adamu, I’d love to conclude with your thoughts on what makes an abolitionist film.

AC: During the process of working on the film, there were people who were putting that question in my ear, and I was trying to avoid it, to be honest. Abolition is on the lips of a lot of people. A lot of people are claiming that as an identity, as a political orientation. I think in some ways having this ideological framework is important. It’s important to have a political stance and political position on certain things. But I often think about the mothers and the loved ones who fight for people every single day, and maybe don’t claim that identity or title. They are doing some of the most radical stuff, which is just loving people whom others can’t even fathom loving.

Something that I sometimes feel is lost is that this is actually about people, it’s not just about systems. It’s not just about having the right set of politics. It’s also about: Where are your relationships at? All of this work is about showing what is actually at the core of what we’re trying to shift, which is this set of relationships that necessitates prisons, that necessitated slavery, that necessitates all of these other exploitative arrangements. There is a certain set of relationships that needs to be undone.

Image: Courtesy of Working Films