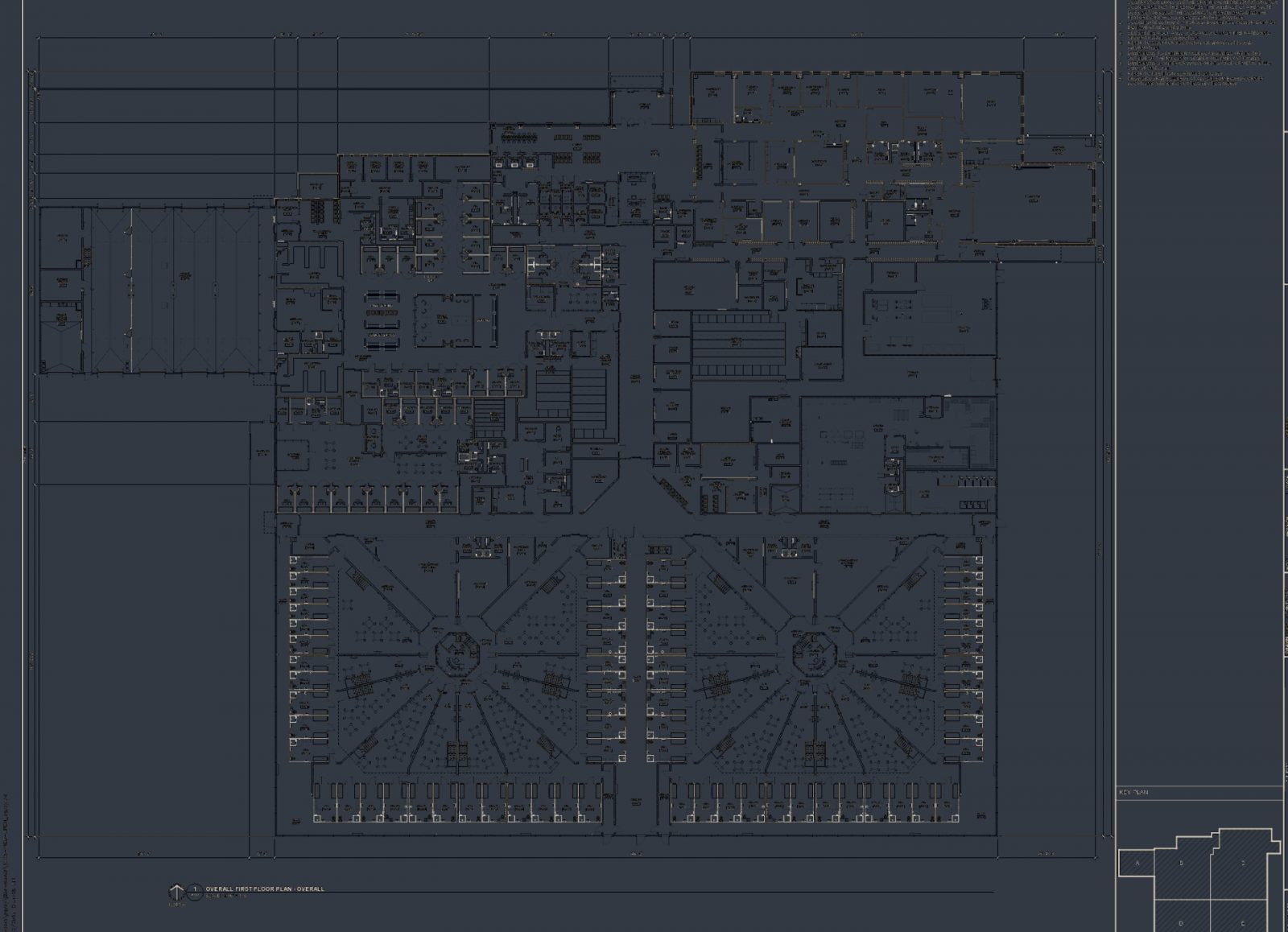

The U.S. carceral landscape is a loose network of sites of detention that includes jails and prisons, along with detention centers, prison camps, and juvenile detention centers. Despite the fact that these buildings each play distinct roles within legal processes, the interior spaces of carceral environments appear nearly one and the same.

In particular, the buildings share similar spatial organizations, most often a row of cell blocks organized around and oriented onto a central indoor recreation room, or a dayroom flanked by double-loaded corridors (i.e., rooms on both sides) filled with cells. Their material expression, too, is similar: the buildings are overly reliant on cold and acoustically reflective concrete masonry blocks, steel, and plastics, boasting undersaturated and austere aesthetics. Jails and prisons alike are littered with security mechanisms that syncopate passage through their hallways, in which metal doors and gates control passage from one space to the next. In these building typologies, there is a noticeable absence of natural light: the sun filters through narrow windows, and abrasive fluorescent lighting compensates for the resultant darkness.

The architectural manifestation of carcerality is created from a design vocabulary of retributive justice that projects an overall image of criminality. From the exterior expression to their harsh interiors, carceral spaces frame the narrative around criminal procedure. Because these spaces all look and feel similar, someone incarcerated—regardless of institutional and of legal status—inhabits a space implicitly rooted in assumed guilt.

New Series

Carceral Geographies

Essays exploring how mass incarceration shapes, and is shaped by, our shared world and built spaces.

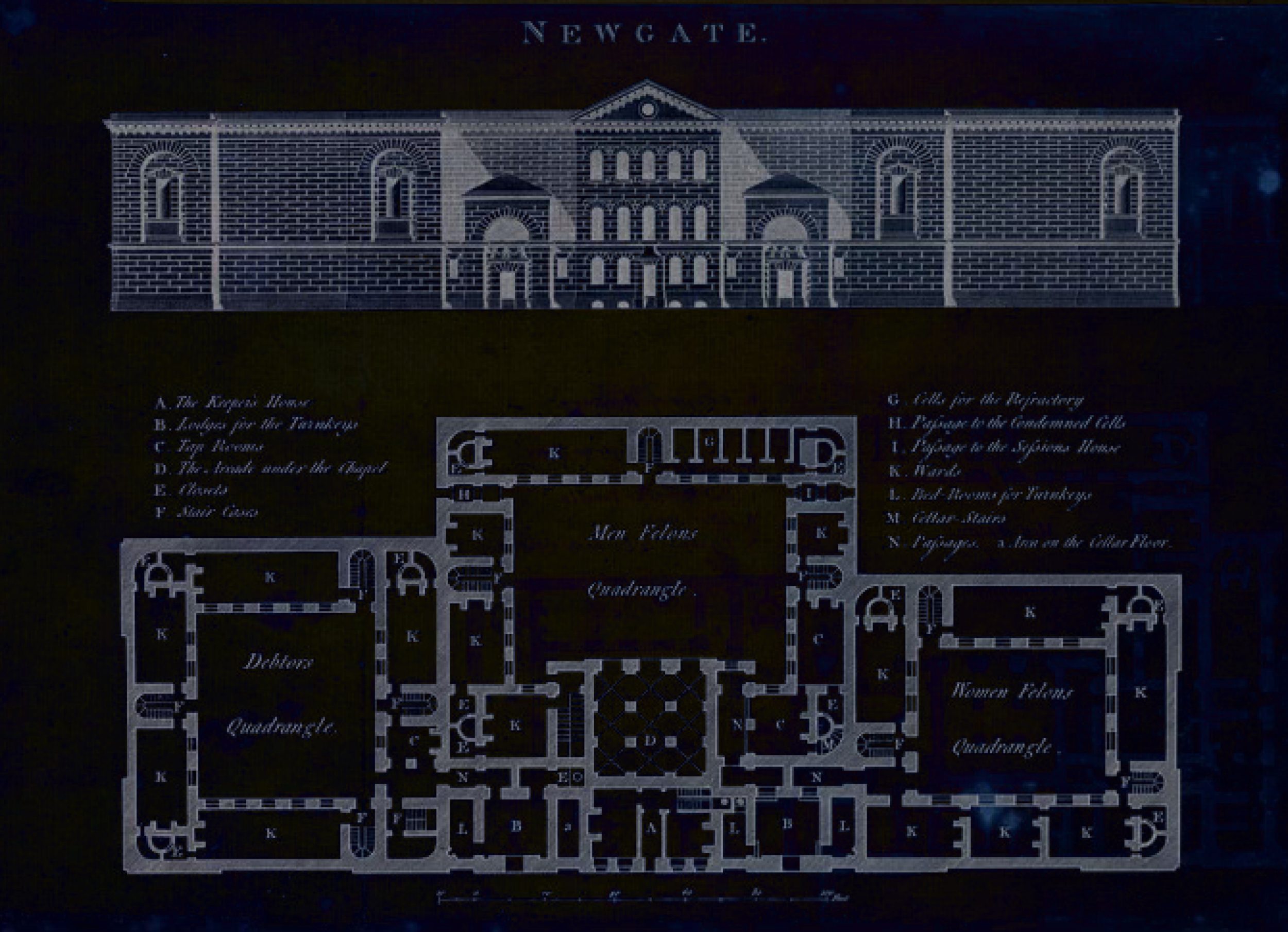

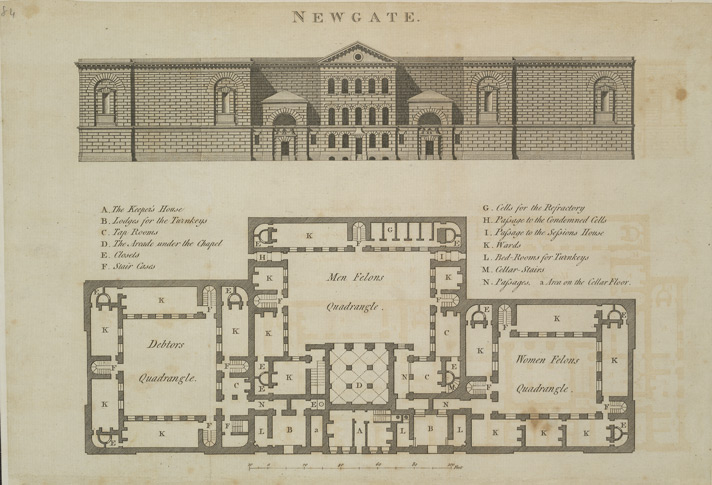

The “birth” of the prison as a legible architectural type is often said to be English architect George Dance’s reconstruction of Newgate Gaol (1780). The medieval gatehouse that Dance’s building replaced had been used as a jail for over 400 years, and the notorious site was framed by early eighteenth-century social reformers as prototypically medieval: an unruly and chaotic space believed to foster an unhealthy environment detrimental to those inside and out of the building’s walls.

By contrast, Dance’s reconstructed Newgate signaled that the prison constituted a building type that could be designed to promote social good, and one that would require a specific visual language. Dance’s project for Newgate—one of the first jail buildings designed by a prominent figure in the profession—brought a formerly “uncontrollable” space into the purview of professional architects, who aimed to shape spaces better suited to their purpose. Newgate projected a clear image of carcerality now tamed: somber, windowless walls punctured only by an entrance festooned with ornamental shackles.

The years that followed saw a flurry of new prison designs, accompanied by widespread debates regarding the proper form of legal punishment. Two important U.S. models—Auburn Prison (1816) in Auburn, New York, and Eastern State Penitentiary (1829) in Philadelphia—refined ideas regarding how to manage their respective populations of what was then widely spoken of as “criminal characters.” At Auburn (now known as the Auburn Correctional Facility and still in use today as a maximum-security state prison), incarcerated people were housed in individual cells, and made to work collectively under enforced silence. This so-called Auburn System (sometimes known as the Congregate System) contrasted with the Philadelphia System, which was based on Quaker ideals. At Eastern State, where the Philadelphia System was fully implemented to widespread admiration, imprisoned people were held in near-total isolation throughout their sentence, with the idea that solitary reflection would lead to repentance and reform. Both the Auburn System and the Philadelphia System positioned criminality as a socially learned behavior; both models required specific architectural forms. These designs captured worldwide attention.

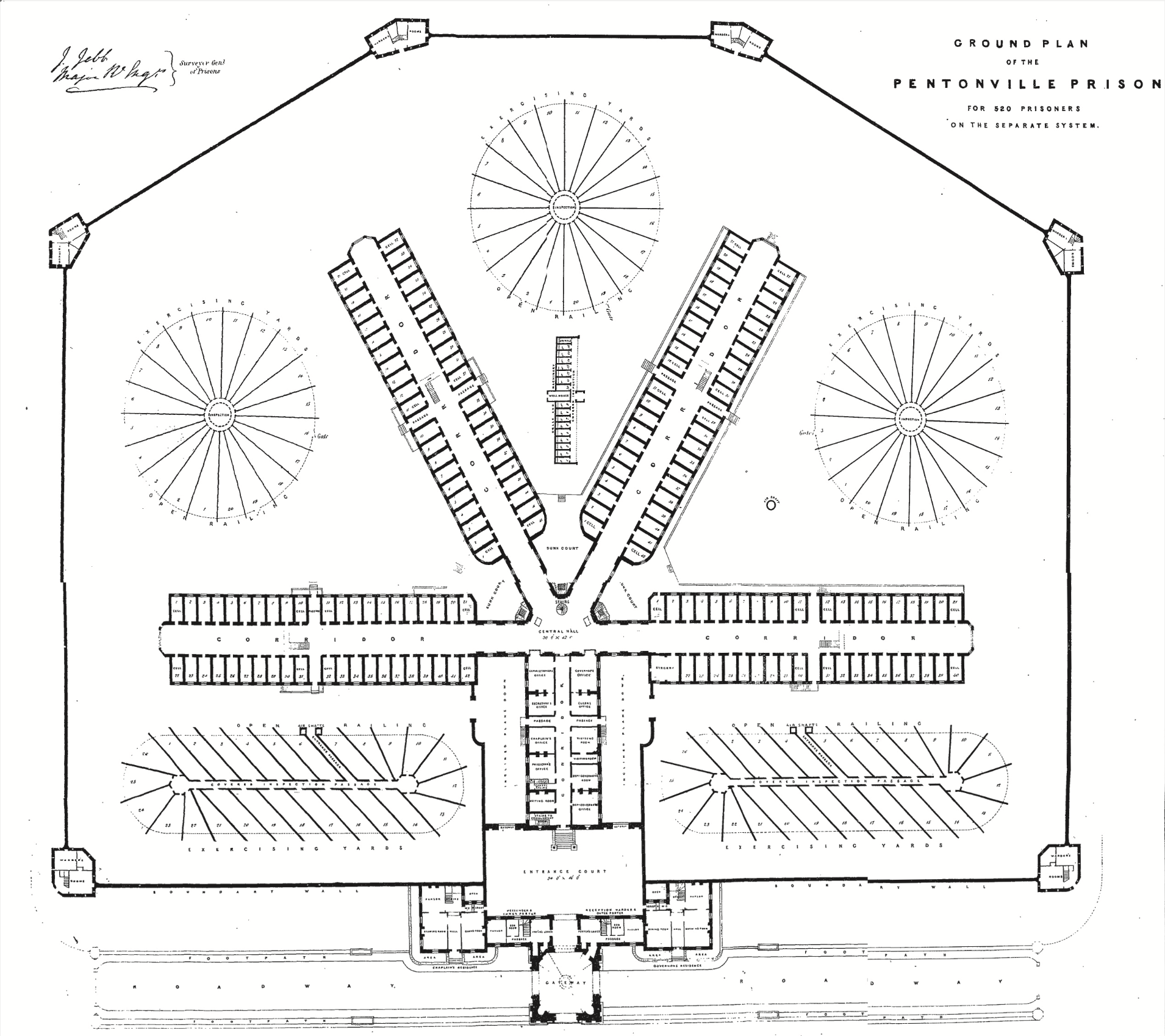

The functional development of the modern penitentiary soon reached its apex back across the Atlantic. If Dance’s Newgate building had signaled that the prison was worthy of architectural expression, the construction of England’s National Penitentiary at Pentonville (1842) was the ultimate realization of the modern penitentiary as a functional type. This building, designed by military engineer Joshua Jebb and architect Charles Barry, demonstrated the full potential of architectural innovation with regard to imprisonment. Pentonville exemplified what had become the leading penal ideology, which relied on a close connection between abstract concepts of legal sanction and the material reality of the prison space itself.

This new prison architecture had developed in parallel with rapid changes in sentencing law. Replacing fines, corporal punishment (including capital punishment), and transportation to overseas colonies, the legal sanction of the prison sentence—imprisonment inside a designated building for a fixed term—became the norm across much of the West by the mid-nineteenth century. The prison sentence was framed as an ideal form of legal sanction: with the intention of being graduated in accordance with the severity of offense, it provided a form of punishment that could be objectively calibrated in response to any given wrong. The prison sentence as a nonarbitrary, proportionable, and thus fair punishment was, in part, produced through the geometries of the prison building itself. The basic architectural form of the prison was thought to provide a standardized metric of punishment that would only vary in terms of the length of time that an individual would occupy it.

In other words, Pentonville Penitentiary, and the legal ideas that it supported, needed a specific architectural form to function properly. Not only did the built space of the prison clearly allow for the physical separation and control of the people who inhabited it, but the ideological work of the prison extended beyond its material walls. Through the architectural drawings that professional architects produced, the prison’s “objective” and legible form was broadly disseminated to a lay audience. The geometric arrangements of identical cells produced a common discourse regarding the prison building that could easily be translated to legal ideology: the prison sentence pictured clearly as a rational punishment.

These earliest purpose-built penitentiaries created a built environment embedded with this ideology, and it continues to inform the construction of carceral spaces today. It is important for this reason to recognize that, even from its earliest days, the architectural project of the “rational” prison was a failure. These failures became almost immediately apparent, and quite publicly so: for example, the year after Pentonville opened, what we would now call a mental health crisis—caused by the penitentiary’s imposition of solitary confinement—was widely publicized. The response from architects, however, was not reengagement—a return to the drawing board—but rather a permanent distancing of the discipline from conversations in prison design. As a result, carceral architecture became essentially frozen in time.

The idea that purpose-built prison buildings would allow for an easy translation between severity of offense and length of sentence was, and remains, a fiction crafted by the geometric regularity of the penitentiary’s architectural plans. A continued (though perhaps unspoken) public faith in the “neutrality” of the prison building perpetuates several related harms.

First, at a macro scale, by confirming the “rationality” of the prison sentence through its regularized architectural form, the buildings provide a useful alibi for those who police and disproportionately incarcerate Black and brown communities. Here we see one more instance of ostensibly race-blind law used to perpetuate racist legal practice.

Second, at the scale of the individual, little attention is paid to the compounding effects produced by carceral architecture in those serving long sentences, nor are the long-term effects of years spent in these spaces typically considered as part of reentry.

More from our decarceral brainstorm

Every week, Inquest aims to bring you insights from people thinking through and working for a world without mass incarceration.

Sign up for our newsletter for the latest.

Newsletter

Third, while the prison sentence can be understood in relative proportional terms in general (ten years is a larger burden than two), a focus on this temporal metric has allowed sentencing courts to substantially discount the disparate physical conditions of penal institutions. How incarcerated people experience punishment is very much contingent on the physical space of the prison, and how that space is designed and managed. This should be obvious. And yet, as we can see in recent “conditions of confinement” rulings, judges tend to focus on penal theory rather than the necessary material reality of its implementation. As articulated explicitly in Justice Clarence Thomas’s Helling v. McKinney (1993) dissenting opinion, “judges or juries—but not jailers—impose ‘punishment.’” A continued legacy of nineteenth-century penal reform is that prison architecture itself—while fundamentally material for those who occupy these spaces—has been rendered into an abstract idea for those on the other side of a judge’s bench.

The legacy of prison reform and design resonates today as these concepts have shaped an entire landscape of carceral facilities and penal practices. The astringent expression of carceral facilities—including the codification of solitary confinement—has resulted in contemporary conditions of oppression, trauma, and dehumanization. The legacy of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century projects continues to shape these landscapes: the austere vision of carcerality that we have inherited from buildings such as Dance’s Newgate broadcasts a message that anyone incarcerated must be “criminal.” The rational planimetric organization of modern prisons allows those in power to tell a fiction about the fairness of criminal law.

Today the United States stands on a carceral legacy of implied criminality and guilt. With increased scrutiny of the criminal legal system at large, in conjunction with an aging infrastructure of jails and prisons, counties, states, and the federal government stand at a crossroad of how to move forward—to rebuild or to shutter. For the most part, new carceral constructions take on a similar form and aesthetic as the previous inhumane institutions. Less often, other models explore neighborhood-based solutions and trauma-informed design.

Standing at this junction, architects and designers cannot simply refuse engagement with this scrutiny, as their disciplines’ forebears largely did. We must accept as an ethical burden the role that our fields have played in creating carceral landscapes that have proven detrimental to recovery, reintegration, and broader community health across the last two centuries. Throughout our history, designers have proven to have a direct hand in the engineering and manifestation of the criminal legal system, and standing in this moment, we have the opportunity to course correct.

Editors’ Note: This article begins a new Inquest series, Carceral Geographies, reflecting on how mass incarceration shapes, and is shaped by, our shared world and built spaces. New essays in the series will appear every other week for the remainder of the summer.

Header image: Plan of Newgate Prison. See in-text figure caption for details.